Home » Jazz Articles » Building a Jazz Library » George Coleman: An Alternative Top Ten Albums

George Coleman: An Alternative Top Ten Albums

There are certain people that are well publicized. Me, I've always been in the background. I've never been bitter about it. I've played with some of the great players in the business. Didn't sound too bad. Made a few records of my own. I feel like I can be happy.

—George Coleman

Glittering careers have been built on flimsier foundations. Yet Coleman's reputation among musicians, which is mountain high among almost all of them (about which more below), has not transferred into a commensurate profile with the wider jazz audience. Coleman's following, passionate though it is, has always been niche.

One of Coleman's nicknames is Big George, another is The Memphis Monster. Both suggest the character of Coleman's high-voltage playing, but neither hints at the lyricism he brings to ballads, nor his harmonic sophistication, nor the outside eruptions which punctuate his essentially inside improvisations.

In a complicated world, simplicity pays dividends and it is possible that Coleman's style is too multifaceted for its own marketable good. This goes some way towards explaining why he has not received the recognition he deserves. In addition, Coleman has never made a calculatedly "commercial" record in his life, under his own name or anyone else's. He has followed his muse, not mammon.

Another explanation for Coleman's marginalisation is that, following City Lights, he was in no apparent hurry to start a solo career. It seems he chose not to pitch to Blue Note after making that album or after being featured on others by pianist Herbie Hancock, drummer Elvin Jones and organist Jimmy Smith. Then again, perhaps he did pitch, but was turned down. Blue Note was fallible. The story of how the label allowed saxophonist John Coltrane to slip through its fingers in 1955 is well known. Less well known examples include pianist Barry Harris. In an interview with Cadence magazine in 1977, Harris said that, following his performances on Lee Morgan's The Sidewinder (Blue Note, 1964) , "I went to [Alfred Lion] and I asked him why didn't he give me a record date. He said I played too beautiful."

But the indications are that Coleman has never made a serious attempt to get into bed with a label with enough clout to bring him to a wider audience, and neither has he had an ambitious manager doing the hustling for him. Nor has he prioritized short-term financial interests. For instance, he quit the Miles Davis quintet in 1964, at the height of its popularity, after being a member for little more than a year. His reasons have never been clear, although we know that the band's drummer, Tony Williams, frequently urged Davis to replace Coleman with a more explicitly "new thing" player, sometimes in Coleman's hearing.

Cruelty to children is a terrible thing, but many people would have forgiven Coleman had he given Williams a clip round the ear. (Just like they might have done had Elvin Jones similarly admonished Rashied Ali in 1966). In any case, to borrow Lester Young's description of being in the proximity of white racists, Coleman felt a breeze, and may have decided he did not need it.

In an interview with Downbeat in 1980, Coleman explained his decision to leave Davis differently. "Miles was ill during that time and a lot of times he wouldn't make the gigs and it was frustrating," said Coleman. "His hip was bothering him. So there was a lot of pressure on me. And sometimes the money would be late and I'd get a cheque and have to try and get it cashed, so I really got tired of it, so I just decided to leave."

The bottom line, fortunately, is that Coleman appears fulfilled by the way his career has turned out. In an All About Jazz interview with R.J. DeLuke in 2002, he said: "There are certain people that are well publicized. Me, I've always been in the background. I've never been bitter about it. I've had people say, as a matter of fact it sounds like a broken record, 'Man, you should be this...Why don't they give you what you deserve,' and all that. I feel I've done enough. I look at myself and I say I've accomplished enough. I've played with some of the great players in the business. Didn't sound too bad. Made a few records of my own. With all these things, I feel like I can retire and be happy." In 2015, America's National Endowment for the Arts honoured Coleman with a Jazz Master Award.

GEORGE COLEMAN: TEN TOP SIDEMAN ALBUMS

Instead of focusing on the albums Coleman has recorded leading his own bands, all of which are highly recommended, this Top Ten chooses from those Coleman has made as a featured sideman. Many of these accord him a prominence akin to that of the leader. But as with any musician who has enjoyed a career as long and distinguished as Coleman's, selecting just ten so-called top albums is a tough task however you cut the cake. The choice of albums below is wholly subjective; there are plenty of other worthy contenders.The smallest lineup here is a trio, the largest a sextet, and most are quartets or quintets. Albums made with bigger ensembles, which offered more limited solo opportunities, such as the excellent ones Coleman made with bassist Charles Mingus and trumpeter Charles Tolliver, have been excluded. The list is chronological. Unless stated otherwise, Coleman is playing tenor saxophone.

Hopefully you will find one or two items that have so far escaped your attention or which may have faded from memory.

Lee Morgan

Lee MorganCity Lights

Blue Note, 1957

Lee Morgan's City Lights is Coleman's jazz recording debut. His style is still developing, so the album is a significant historical marker. Little acorns and so on. But not so little in this case. On the opening title track, Coleman delivers a tenor solo that is a harbinger of the full-throttle head charge which marks his mature up-tempo work. On the closing "Kin Folks," a mid-tempo blues, he delivers a soulful alto solo. Between times there is another tough tenor solo on "Just By Myself" and a lyrical alto one on "Tempo De Waltz." (All four tunes, incidentally, were written by tenor player Benny Golson). August 25, 1957 was a busy day... Once the City Lights session was over, Coleman, Morgan and trombonist Curtis Fuller, along with producer Alfred Lion and engineer Rudy Van Gelder, decamped from Van Gelder's New Jersey studio to a studio in Manhattan for a Jimmy Smith session, recording tracks included on Smith's albums House Party (Blue Note, 1958) and The Sermon (Blue Note, 1959).

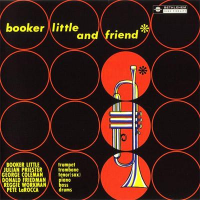

Booker Little

Booker LittleBooker Little & Friend

Bethlehem, 1961

Trumpeter Booker Little's Booker Little & Friend (the reference is to Little's horn) is hard bop with a harmonically adventurous edge, and is widely regarded as Little's chef d'oeuvre. Coleman and Little were good friends; they were born within three years of each other in Memphis, where they went to the same high school, and both migrated north to Chicago in 1955. Soon afterwards, drummer Max Roach recruited them for his band. The duo recorded together, under Roach and Little's separate leaderships, from late 1957 until 1961, when, a few months after making this album, Little passed at the tragically young age of twenty-three (from kidney disease, not heroin, the usual suspect). The line-up is completed by trombonist Julian Priester, pianist Don Friedman, bassist Reggie Workman and drummer Pete LaRoca.

Miles Davis

Miles Davis In Europe: Recorded Live At The Antibes Jazz Festival

Columbia, 1964

A credible argument can be made that Miles Davis' so-called second great quintet was not, as conventional wisdom holds, the 1964-68 one with tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter, pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams, but the one which preceded it in 1963-64. While this band also included Hancock, Carter and Williams, Coleman was the tenor saxophonist. In Europe: Recorded Live At The Antibes Jazz Festival, recorded in June 1963, contains hints of the semi-free abstraction which Davis was to pursue in the lineup with Shorter (which in the new scheme of things becomes Davis' third great quintet). This is balanced by Davis' and Coleman's continuing, captivating engagement with changes-based originals and material from the great American songbook, which, ultimately, wins the day.

Miles Davis

Miles Davis My Funny Valentine: In Concert

Columbia, 1965

Eight months later and Davis' band is inching further along the route towards abstraction. But the destination is still some distance off and My Funny Valentine: In Concert is in the same blissful ballpark as the Antibes performance. The album was recorded at the Philharmonic Hall, Lincoln Center in February 1964. So was Four And More: Recorded Live In Concert (Columbia, 1966); Columbia decided to separate out the slower and faster tunes, putting the slower ones on My Funny Valentine. Exquisitely lyrical, this is one of the great live albums of its era, ranking alongside other landmarks such as pianist Bill Evans' Sunday At The Village Vanguard (Riverside, 1962). One cannot help but wonder how things might have panned out if Coleman had stayed in the quintet longer. Maybe Davis' full-on embrace of chromaticism would not have happened. But what-if history is a mug's game.

Herbie Hancock

Herbie Hancock Maiden Voyage

Blue Note, 1965

Coleman quit the Davis quintet shortly after the 1964 Lincoln Center concert, and, as noted earlier, it is likely that one reason for his decision was that he was made to feel unwelcome by Tony Williams. In Miles: The Autobiography (Simon & Schuster, 1989), Davis said: "Tony Williams never liked the way George played, and the direction the band was moving in revolved around Tony. George was a hell of a musician... but Tony wanted someone... like Ornette Coleman... Sometimes when I would finish my solo and start to go in the back, Tony would say to me 'Take George with you.'" We know that Herbie Hancock held Coleman in high regard, however, because he chose Coleman as the saxophonist for the March 1965 session which produced his early masterpiece, Maiden Voyage, in a lineup completed by trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, Ron Carter and... Williams (suck that up).

Mal Waldron

Mal Waldron Sweet Love, Bitter

Impulse, 1967

In 1963, pianist Mal Waldron suffered a mental and physical collapse triggered by a heroin overdose, from which he took three years to recover. Sweet Love, Bitter was among the first albums Waldron recorded on his return to the scene, and it focuses on the bleak, minor-keyed vibe which typified his post-recovery work. The music was the soundtrack to a movie starring Dick Gregory as an over the hill, dope-addicted saxophonist modelled on Charlie Parker. By all accounts, the movie is nothing special, but the soundtrack is outstanding. Waldron leads a sextet comprising Coleman, on alto throughout, Charles Davis on tenor, Dave Burns on trumpet, Richard Davis or George Duvivier on bass, and Al Dreares on drums. Coleman's performance of the theme tune, "Loser's Lament," is suitably noir and he is showcased to advantage on several other tracks.

Elvin Jones

Elvin JonesLive At The Village Vanguard

Enja, 1968 / 1974

If we need affirmation of Coleman's talent (and we do not), his presence in drummer Elvin Jones' pianoless trio in 1968, the year following the passing of Jones' longtime employer, saxophonist John Coltrane, speaks for itself. Live At The Village Vanguard has Coleman in magisterial form alongside Jones and bassist Wilbur Little. Running time is just over forty minutes and Coleman is centre stage for thirty of them. There are four tracks. Coleman's boppish "By George" opens and includes the first of just two Jones solos on the album. Next up is David Raskin's poignant "Laura," which runs for twelve minutes; Coleman is on-mic from start to finish, in affecting ballad mode. Keiko Jones' perky "Mister Jones" includes another extended Coleman workout. The closer, Gene de Paul's "You Don't Know What Love Is," has Coleman once again on-mic throughout. Audio quality is not great, which may be why the album was not released until 1974. But it is good enough. Coleman also features, albeit in larger lineups, on Jones' albums Poly-Currents (Blue Note, 1969) and Coalition (Blue Note, 1970).

Roy Brooks

Roy BrooksThe Free Slave

Muse, 1972

Drummer Roy Brooks' The Free Slave is one of the neglected masterpieces of spiritual jazz. Brooks spent much of the 1960s in bands led by pianist Horace Silver and multi-reedist Yusef Lateef, with whom he shifted his trajectory from feelgood hard bop towards a muscular form of modally based spiritual jazz. Brooks suffered from mental health issues throughout his life and was off radar for much of the late 1960s. He returned to view in the early 1970s, when The Free Slave was recorded live at Baltimore's Left Bank Jazz Society. Coleman shares the frontline with trumpeter Woody Shaw and the band is completed by pianist Hugh Lawson and bassist Cecil McBee. Unlike Elvin Jones on Live At The Village Vanguard , Brooks takes his full share of the solos, which means Coleman's time in the spotlight is limited. But the level of his playing, and the overall quality of the album, makes it worth its weight in gold (something often reflected in the asking price).

Cedar Walton

Cedar WaltonEastern Rebellion

Timeless, 1976

A magnificent album from a quartet led by pianist Cedar Walton and completed by bassist Sam Jones and drummer Billy Higgins, each of them in top form. The performances are mostly heated and up-tempo and Coleman's romping broken-note strewn tenor is prominently featured. The album opens and closes with two familiar Walton pieces, "Bolivia" and "Mode For Joe," between which sit John Coltrane's "Naima," Coleman's "5/4 Thing" and Jones' "Bittersweet." Coleman's expansive treatments of "Naimi" and "Ode For Joe," pieces indelibly associated with Coltrane and Henderson, are fresh hewn and stand shoulder to shoulder with the originals. Between 1977 and 1984, Walton released volumes 2, 3 and 4 in the Eastern Rebellion series, but this is the only one featuring Coleman.

Ahmad Jamal

Ahmad JamalÀ L'Olympia

Dreyfus Jazz, 2001

This album, recorded in concert in Paris in late 2000 to celebrate pianist Ahmad Jamal's seventieth birthday, is the second disc Coleman has made with Jamal. Live In Paris 1996 (Dreyfus) is good but À L'Olympia is better, partly due to the choice of material and partly because of the lineup, a quartet completed by bassist James Cammack and drummer Idris Muhammad. The set includes extended versions of Jerome Brainin's "The Night Has A Thousand Eyes," Irving Berlin's "How Deep Is The Ocean," Joseph Kosma's "Autumn Leaves" and Victor Young's "My Foolish Heart." You can get a taste on the YouTube clip below, which at ten minutes is a shorter version of "My Foolish Heart." The album is the equal of anything among Coleman's earlier work and it confirms him as one of the greatest tenor saxophonists of all time.

< Previous

John McLaughlin, Jeremy Green, Steve ...

Comments

About George Coleman

Instrument: Saxophone, tenor

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

Building a Jazz Library

George Coleman

Chris May

Max Roach

lee morgan

Herbie Hancock

Elvin Jones

Jimmy Smith

John Coltrane

Barry Harris

Miles Davis

Tony Williams

Rashied Ali

Lester Young

Charles Mingus

Charles Tolliver

benny golson

Curtis Fuller

Alfred Lion

rudy van gelder

Booker Little

Julian Priester

Don Friedman

Reggie Workman

Pete LaRoca

Wayne Shorter

Ron Carter

Bill Evans

Ornette Coleman

Freddie Hubbard

Mal Waldron

Charlie Parker

Charles Davis

Dave Burns

Richard Davis

George Duvivier

Al Dreares

Wilbur Little

Roy Brooks

Horace Silver

Yusef Lateef

Woody Shaw

Hugh Lawson

cecil mcbee

Cedar Walton

Sam Jones

Billy Higgins

Ahmad Jamal

James Cammack

Idris Muhammad

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.