Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Enrico Rava: To Be Free or Not To Be Free

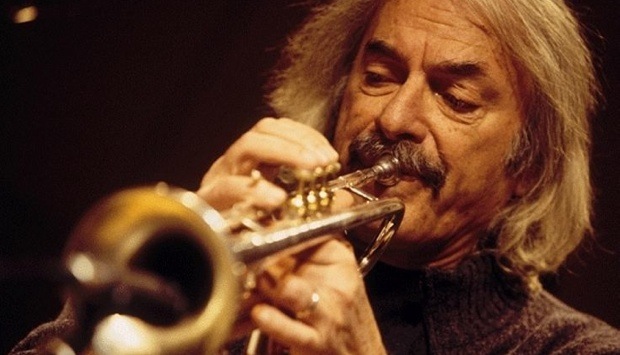

Enrico Rava: To Be Free or Not To Be Free

Since returning to the ECM fold in 2004 after a 15-year hiatus, Rava has produced some of the most important music of his storied career. Albums like Easy Living (ECM, 2004), TATI (ECM, 2005), The Words and the Days (ECM, 2007), The Third Man (ECM, 2008) and New York Days (ECM, 2008) have shown Rava to be enjoying a late-career high, playing and composing better than ever. Although he doesn't consider himself to be a talent scout, his working groups have allowed a stream of young talent, including pianists Stefano Bollani and Andrea Pozza, trombonist Gianluca Petrella and bassist Rosario Bonaccorso, to step into the international spotlight.

Tribe (ECM, 2011) is another powerfully seductive offering from Turin- born Rava. There are a couple of familiar faces in the lineup, like drummer Fabrizio Sferra and Petrella, but, not for the first time, some talented newcomers throw their hats into the ring, challenging and inspiring Rava once more. Pianist Giovanni Guidi, bassist Gabriele Evangelista and guitarist Giacomo Ancilloto bring a youthful zeal to the ensemble sound, and will all be names to watch out for. Rava gets the best of the musicians around him by allowing them the utmost freedom to express themselves within the confines of his very democratic tribe.

All About Jazz Does the title Tribe have any special significance for you?

Enrico Rava: It didn't have it at the beginning. I recorded it in 1975 with [guitarist] John Abercrombie, [bassist] Palle Danielsson and [drummer] Jon Christensen, for ECM. My pianist now [Giovanni Guidi] wanted to play it and I said, "Why not?" It sounds very contemporary. But now that I've recorded it, I think that Tribe is not only the right title for the CD but also for my band because really I feel it's like a tribe-a very democratic tribe.

AAJ: On Tribe, you've recruited a couple of old colleagues in trombonist Gianluca Petrella and drummer Fabrizio Sferra, and a few newcomers in bassist Gabriele Evangelista, pianist Giovanni Guidi and guitarist Giacomo Ancillotto. Were you specifically looking for a balance between old and new blood for this CD?

ER: No, no, no. I call the musicians because I like them. They can be 16 years old or 95 years old. I'm not a talent scout. It often happens that they are very young because the young musicians are closer to my vision of the music and they have a lot of energy. I don't like too much to play with people of my age. I feel closer to younger people, but there are some contemporaries of my age who have the same vision I have. I play with them very often, and I'm very glad to do it.

AAJ: Who, for instance?

ER: One of the very few Italian musicians of my age who I enjoy playing with is [pianist] Franco DAndrea. Another is The Dino & Franco Piana Jazz Orchestra, a great pianist and composer. Dino Piana-who is now 82-played all his life in a radio orchestra, but when he was about 30 and I was 20, he was just playing jazz. Everybody wanted to play with him all over Europe, but then he joined the orchestra. When he retired, he started playing only jazz. When I have the possibility I call him, and for me it's always a great pleasure to play with him because he's very open. [drummer] Aldo Romano is another musician. But most of the musicians of my age tend to stick to what they were doing when they were at the top of their trend, and that's no good for me.

ER: One of the very few Italian musicians of my age who I enjoy playing with is [pianist] Franco DAndrea. Another is The Dino & Franco Piana Jazz Orchestra, a great pianist and composer. Dino Piana-who is now 82-played all his life in a radio orchestra, but when he was about 30 and I was 20, he was just playing jazz. Everybody wanted to play with him all over Europe, but then he joined the orchestra. When he retired, he started playing only jazz. When I have the possibility I call him, and for me it's always a great pleasure to play with him because he's very open. [drummer] Aldo Romano is another musician. But most of the musicians of my age tend to stick to what they were doing when they were at the top of their trend, and that's no good for me. AAJ: On Tribe your connection with Petrella sounds really intuitive; the pair of you sound like siblings. Tell us a little about what it's like playing with him and what he brings to the mix.

ER: First, let me tell you that I met Gianluca when he was 18. I knew his father, who was a very good trombone player, too. A couple of years later, Gianluca came on a long tour with me in Canada at all the festivals, and he stayed. The rest of the people changed, but he stayed. I have a special relationship with two musicians-one is Gianluca and the other is [pianist] Stefan Bollani-a kind of telepathic thing where when we play it's like we talk to each other all the time. These are the best musical relationships I have had in my life; another one was with [trombonist] Roswell Rudd many years ago. With Gianluca, I have the same kind of rapport.

AAJ: Are there other musicians whom you've deeply connected with over the years?

ER: When I play with somebody, I look for a deep connection, and I had a very deep connection with [alto saxophonist] Steve Lacy at the end of the '60s when I was playing in his band. We had a very strong musical understanding when we played together. I also had that a lot with an alto saxophonist from Italy, who died many years ago, called Massimo Urbani. I brought him to New York when he was 18. Then I had a fantastic thing with [saxophonist] Joe Henderson when we did a long tour together in Europe, which was fantastic. I also really love to play with [saxophonist] Mark Turner; he's a tremendous player, though we play together rarely.

AAJ: You played trombone prior to taking up the trumpet. Do you feel you have a special affinity with trombonists?

ER: Yeah, I do, though my experience as a trombone player was almost nothing. I played in a Dixieland band as an amateur when I was 16, and we were playing [Louis] Armstrong Hot Five tunes, "At the Jazz Band Ball" and "Jammin' the Blues," but I was a very rudimentary player. It lasted a very, very short time. Two years later, I bought a trumpet. But I love the trombone. I like the tone and the register of the trombone, which is the same register as the male voice. If you talk and, while you're talking, you start playing the trombone, it's the same tone and register, while the trumpet is always high pitched-I feel like someone is always hanging me [laughs]. The trumpet and trombone is exactly the same instrument except that one is higher pitched. That's why they sound so good together. I learned that playing with Roswell [Rudd], because he was showing me certain intervals that we were playing together- the two notes we played could generate all the overtones and the harmonics. Sometimes you can play a chord of two notes, but you can hear four or five notes. You can't do that with flugelhorn and trombone because flugelhorn is a different instrument- it's a cornet instrument-but a trumpet is exactly like a trombone except for the higher register.

I like very much that sound. There are a couple of records of the quintet of [trumpeter] Clark Terry and [trombonist] Bob Brookmeyer, and the sound is so beautiful. There are also recordings by trumpeter Conte Candoli and [trombonist] Frank Rosolino; I am a fan of that sound [laughs]. I know all of them.

AAJ On Tribe, drummer Fabrizio Sferra brings a beautiful touch and at the same time great propulsion to the music, particularly on "Planet Earth" and "Choctaw." You've recorded with him before on Full of Life (Cam Jazz, 2005). What do you like about his playing?

ER: I like Fabrizio because he's ready for everything. He's very open, so he can play beautifully in, but he can play very well out. He's open to anything that can happen. He's a very good musician, too. He plays piano, he's a leader of his own band, and he's a composer of very nice tunes, too. He's a very musical drummer. He's not just a rhythmic drummer. All the great drummers-I think of Billy Higgins-are complete musicians.

AAJ: A drummer who lit up couple of your ECM recordings, TATI (ECM, 2005) and New York Days (ECM, 2008), sadly passed away recently. What will be your abiding memories of Paul Motian?

ER: Paul was a master musician, one of the great drummers. He was a very good friend of mine because when I moved to New York, in 1967, I would go his apartment on Central Park West. He was the only person I know who stayed in the same apartment all his life [laughs]. He was there for, I don't know, almost 50 years. It's incredible, because in New York everything changes every two seconds; if you go away one week, when you come back, your friend doesn't live there anymore, the fruit vendor isn't there anymore, your friend who was a taxi driver isn't there anymore. The only thing that didn't change was Paul Motian in Central Park West; everything and everybody else moved.

ER: Paul was a master musician, one of the great drummers. He was a very good friend of mine because when I moved to New York, in 1967, I would go his apartment on Central Park West. He was the only person I know who stayed in the same apartment all his life [laughs]. He was there for, I don't know, almost 50 years. It's incredible, because in New York everything changes every two seconds; if you go away one week, when you come back, your friend doesn't live there anymore, the fruit vendor isn't there anymore, your friend who was a taxi driver isn't there anymore. The only thing that didn't change was Paul Motian in Central Park West; everything and everybody else moved. He was a very good friend, and we played in many different situations; we played in some bands with Roswell [Rudd] and in the Jazz Composers Orchestra with [pianist/composer/arranger] Carla Bley, and we toured together with Joe Henderson, and later with [Stefano] Bollani. He was a fantastic guy, and he was a teenager; he was a young old guy. He was 18 years old in his head. I'm going to miss him. Everybody is going to miss him. He was a different musician, a very unique drummer. He had his own technique, his own sound, and he was very, very creative. You didn't have to ask him to do this and do that. Anyway, he wouldn't do it [laughs], so you didn't ask him to do it; you let him do what he wanted. It was always better than what you would have asked him to do.

AAJ: Let's talk a little about ECM, with whom you've had a long relationship. How was the ECM 40th anniversary bash in Mannheim? It must have been a fun occasion, no?

ER: I remember it very well. I remember everything of that night. I played with [bassist] Larry Grenadier, Mark Turner, but with Jeff Ballard on drums because Paul [Motian] wasn't traveling anymore. We had a very good concert.

AAJ: How had ECM changed in the almost-20-year gap before you returned to record Easy Living in 2004?

ER: Basically, I think it hadn't changed, because Manfred Eicher has a very clear idea of what he wants. He records only musicians that he likes and musicians that he knows he's going to like their music; it's the only law, and in that sense it hadn't changed much. Except that, when I came back, he was giving much more space to contemporary music. Before, he had [composers] Arvo Part and Philip Glass, but now there is much more contemporary music. He's also more open to southern European music, and now there are a few Italians that record for him. Back in the '70s there was me, if we're talking about southern, Mediterranean musicians. But now, besides me, there's Stefano Bollani and [saxophonist] Stefano Battaglia, [clarinetist] Gianluigi Trovesi. And now we did a concert playing only the music of [singer] Michael Jackson for him [Eicher], which is a big surprise for a lot of people.

AAJ: No kidding.

ER: [laughs] I know, I know. You must know that I am a Michael Jackson fan. I like very much the last record. To me, it's a little bit like the Beatles' White Album (Apple, 1968). There is a tune called "Little Susie" that could have been written by [singer/composer] Kurt Weil, and tunes like "Privacy" and "History" are incredible-a little bit like "Sergeant Pepper," in a way. I did this concert with a big band-12 people: tuba, trumpet, piano and clavier, guitar, three saxophones, trombone. We did a concert of Michael Jackson's music in May, and we did another concert on November 30th in Rome, and it should come out soon.

We are going to do a lot of concerts with this program. I like this program of Michael Jackson a lot because it's very energetic and there's a lot of life. The tunes are so good. We only do two of the big hits: one is "Smooth Criminal"-one of my favorite tunes-and "Thriller." On "Thriller" we stay very close to the version done by [trumpeter] Lester Bowie. The way we did the tune was a tribute to Michael Jackson but also to Lester Bowie.

AAJ: That sounds very interesting, and we'll look forward to that. Some of your best music has come since your return to the ECM label in 2004. Does this working relationship completely satisfy musically, or do you still feel the need to record music with a different aesthetic on a different label concurrently?

ER: I did that in the '80s. That's why we stopped recording together. The thing was, Manfred's idea is to record maybe every one and a half years, and at that time I felt I wanted to record much more. I had a lot of different things going on that I wanted to record, and it was impossible to do it at ECM, first of all because it probably didn't fit the aesthetic of the label, and because it would have been too many records. So I started recording with somebody else. When I came back to ECM in 2004, I discovered that in a way Manfred was right; it's better to release a record only once in a while when you are ready. I made so many records in the '80s, and looking back I can see that many of them were not necessary.

This record, Tribe, came out two years after the previous record, and the interest around this record is very big. There have been so many reviews. I think the ECM strategy is the right one. I'm happy with that. Besides, I'm 72. I like what I do to be necessary and important.

AAJ: Manfred Eicher is someone you know well. How would you sum up what he has achieved with ECM?

ER: He has invented a very big label, a very important label with a distinct sound and one of very high quality and with a very good distribution. In a way, it's the only very important independent label. But wherever you go, you find ECM records-in the States, in Korea-it doesn't matter where you go. The records are there, and this is very important for us. But it's not just that. The label has a very distinctive sound, and there are people who buy ECM records just because they are ECM. In fact, in many record stores-even though the record stores are disappearing-in Italy, for example, there is a special section for ECM records.

Manfred is a real artistic director. I remember talking with Paul Motian about the order of the tunes when we did the trio record, TATI (ECM, 2005), and I was saying, "What do you think? Should we put this number one or number two?"

Paul said, "Please let Manfred do that." He told me, "With my records, I let Manfred do that, and I trust him 200 percent. He's always right."

Paul said, "Please let Manfred do that." He told me, "With my records, I let Manfred do that, and I trust him 200 percent. He's always right." Manfred has worked with everyone from classical pianists to [pianist] to Keith Jarrett, the Art Ensemble of Chicago to Arvo Pärt, so he knows how to use the recording machine. He's a real artistic director, and he's a big help in the studio.

Sometimes you go into the studio, and you know exactly what to do, and everything is right, and he doesn't say a word. Other times you go into the studio, for example, when we did Volver (ECM, 1994) with [bandoneon player] Dino Saluzzi. We had a lot of problems, not between me and Dino, because we're very good friends, but between the drummer [Bruce Ditmas] and Dino. The situation was so bad, the atmosphere was so bad, that we couldn't even play. We just sat in the studio and didn't play. So Manfred stepped in and started giving his advice, and he succeeded in starting the whole thing. Eventually the record came out, and it's a pretty good record.

AAJ: You first recorded for ECM in 1975-when the label was a mere pup, at six years of age-with The Pilgrim and the Stars, which was re-released in 2008. How did it sound to your ears after 33 years?

ER: It's funny you should ask me that, because just a few days ago I had this big radio interview where they played a lot of records of mine, and one was "Bella" from The Pilgrim and the Stars. And listening to it now, it sounds like I could have been done it last week. It doesn't sound 35 years old at all. My pianist Giovanni Guidi wasn't even born then. He's a very modern musician, but he keeps saying, "Enrico, why don't we play that tune from Quartet (ECM, 1978) or that tune from Il Giro del Girono en 80 Giorni (Black Saint, 1976)?" He keeps asking me to play tunes that are really old, but in fact when we play them, like "Tribe," it really doesn't sound old at all. It sounds like we did it last week. Some of those tunes feel like contemporary records. I shouldn't say that, because I'm speaking very well of myself [laughs].

Listening to The Pilgrim and the Stars, I was amazed how the three of them sounded-[John] Abercrombie, Palle Danielsson and Jon Christensen. They are unbelievable. I didn't like my playing too much. I am very self-critical. Every time I listen to my playing on records, I get very depressed.

AAJ: So was Giovanni Guidi the driving force behind you going back to revisit some older material on Tribe, like the title track, which dates back to The Plot (ECM, 1976), and "Cornettology" and "Planet Earth" from Secrets (Soul Note, 1987)?

ER: He's the reason for "Tribe." I wanted to play "Planet Earth." I must say that the inspiration for "Planet Earth" comes from Michael Jackson. "Cornettology" is pretty recent, anyway, from TATI (ECM, 2005), and it's a tune that I've kept playing since then because it's a very open tune, in a tribute to [saxophonist] Ornette [Coleman] And the cornet is what Don Cherry used to play, so it's a tribute to both of them. I really like to play it; it's a fun tune.

AAJ: Pianist Guidi is another in a succession of fine pianists: Bollani, Andrea Pozza on The Words and the Days (ECM, 2007). How do you keep finding such great pianists? When did you first come across Guidi?

ER: I first came across Giovanni Guidi when he was four years old, because his father is my agent. He would come sometimes with his father to the concerts. I followed him when he started piano. Besides being my agent, Mario is a very good friend, and every time I phoned him, in the background I could hear Giovanni on piano. It was difficult to talk because there was always this guy playing piano. Then I did a couple of tours in Italy with [saxophonist] Gato Barbieri, and I had Giovanni play piano for the sound check, and I saw that he had something special going on. Then he came to a workshop I did in Siena, and I knew that he was a very accomplished musician.

For a while, I had a band called Under 21, which was all young people, and he was the pianist. When that group disbanded, he became my pianist. In the meantime, I changed the bassist and the drummer, so I was changing a little the rhythmic idea, and I thought Giovanni was better for that equation. Andrea [Pozza] was great on that record, The Words and the Days, and a great band with [drummer] Roberto Gatto and [bassist] Rosario Bonaccorso. Andrea was extraordinary, and in fact, I think some of the best moments of that record are when Andrea solos. But it was time for a change because the music was getting too kind of mainstream in a way, and we were playing all the same stuff, and there was no surprise anymore. Roberto had his own band, so his head was somewhere else. Same thing with Roberto Bonaccorso-who I like a lot-he had his own big band and his composer's head was somewhere else, and the band wasn't happening anymore. I wanted to change everybody, except for Gianluca [Petrella], of course.

AAJ: Petrella's playing is great throughout Tribe. Why make "Garbage Can Blues" a piano trio piece? Why did you and Petrella sit that one out?

ER: Actually, "Garbage Can Blues" was supposed to be only the end of "Cornettology," but Manfred [Eicher] liked the melody so much, and he suggested we do a short version with just piano, some drums and bass, but mainly piano with everybody else like a shadow. It was just to create a little interlude, let's say, though it kind of connects to the end of "Cornettology."

AAJ: These days, Norway has a world-wide renown for producing great jazz musicians, but it seems that there are an awful lot of excellent musicians and composers in Italy, too. Where would you situate Italy in terms of the quality and quantity of jazz music coming from there?

ER: I think Italy today is in a very good position-one of the main countries in Europe for sure, in terms of great young musicians and composers. It's also true that Italy has become one of the best markets for jazz. We have a lot of great American bands playing all the time everywhere in Italy. We have a lot of amazing trumpet players and a lot of really amazing piano players, bassists and saxophonists. We have composers of big band groups, and these musicians get younger and younger. I don't know how it has happened; there are really a lot of musicians. I just ask myself what they are going to do, because in Italy we are in a very heavy crisis at this moment, all over Europe in fact, and the work is much less than before. For well- known people like myself, [trumpeter] Paolo Fresu or Bollani there is work enough, but for the young, unknown musician it's not so easy.

ER: I think Italy today is in a very good position-one of the main countries in Europe for sure, in terms of great young musicians and composers. It's also true that Italy has become one of the best markets for jazz. We have a lot of great American bands playing all the time everywhere in Italy. We have a lot of amazing trumpet players and a lot of really amazing piano players, bassists and saxophonists. We have composers of big band groups, and these musicians get younger and younger. I don't know how it has happened; there are really a lot of musicians. I just ask myself what they are going to do, because in Italy we are in a very heavy crisis at this moment, all over Europe in fact, and the work is much less than before. For well- known people like myself, [trumpeter] Paolo Fresu or Bollani there is work enough, but for the young, unknown musician it's not so easy. I worry for them. It's very difficult right now. The crisis that everybody is talking about is really there. When I started playing jazz in Italy, there were just three musicians making a living from just playing jazz. There were very good musicians, but everybody else was playing in a radio orchestra or with singers. But people living from playing jazz, and not commercial music, we were three guys. Now there are hundreds, and they just play jazz and they don't want to do anything else, which is what I did all my life. When I was young, it was a very crazy decision, and my family was very worried about me. But today so many people try to live out of jazz, and I hope they can keep doing it.

AAJ: Another great young talent is bassist Gabriele Evangelista. It sounds like you gave him a lot of freedom on this CD. Is that the case?

From left: Gabriele Evangelista, Enrico Rava, Gianluca Petrella

ER: I give a lot of freedom to all the band, within a frame, and this frame is my vision of the music. Within this frame, they can do what they want. I never ask them to do this or that. Very rarely [do] I bring an arrangement or anything like that. I just bring melodic lines and chords and say a few words what I would like to happen; then everybody has to find his own way. That is why they sound so good. I didn't invent that. I learned that from [trumpeter/leader] Miles [Davis]. Miles used to do that. That's why every musician who played with Miles played his best when he played with Miles. [pianist] Red Garland, for example, was a great pianist out of Miles' group, but with Miles his playing is very, very special because he had all the freedom he needed.

With me, the musicians also have a lot of freedom. But when I choose a musician to be in my band, I think about it. I only call musicians that I love and who I can trust musically. I give them a lot of freedom because I trust them. I have to trust them, and they have to trust me-at that point, everything is possible.

AAJ: In the '60s and '70s you played with a host of musicians like Don Cherry, [pianists] Mal Waldron and Cecil Taylor, [saxophonists] Steve Lacy, Marion Brown and Evan Parker, Roswell Rudd, [drummer] Rashied Ali-all the free-jazz people. Is it possible to compare the freedom in your group's playing today, with the freedom that existed in the free-jazz thing of those years of which you were a part?

ER: Yeah, I can. I think there is more freedom now. Of course, we are talking about records, and records are a different thing. You are very cautious if you are recording, and you are conscious about playing too long. But when we play live, the music can go anywhere and can become free in the sense of the free jazz you are talking about. It can go there, or not. I have a very good story about the free- jazz era; in Europe there was a thing called Free Jazz Meeting in Baden-Baden in Germany, and the producer of that was Joachim Berendt, the German journalist. I did many of these Free Jazz Meetings, and at one of these, [bassist] Eberhard Weber was playing-I don't remember with who-and they were playing this free jazz. All of a sudden, he decided to play a couple of chords, and immediately Joachim Berendt stopped the recording. "Stop!" he said. "Remember, this is a free jazz meeting!" [laughs] You could not play chords, you know?

It's true. That was one of the reasons why I switched back to playing with rhythm and chords-because I felt much freer. If I want, if I like, I can go anywhere. Back then it was "Please don't play this, don't play that." I thought, "Why not?" It was very conceptual, and I didn't like that.

Now in my projects the music can go wherever it wants, if the band feels like it. We can switch to a blues, increase the tempo, or take it completely out for half an hour; for me, it's cool. On a record, this doesn't really happen. It's a different rapport. Maybe you are in a booth and you can't really see each other. Sometimes when playing, it's really important to be able to see the smallest sign. For me, they are two separate arts. Live music is music, but it's also a show. I can remember the first time I saw Miles in '56 in Torino, my hometown. He was playing with [tenor saxophonist] Lester Young, then with some French musicians and then with the Modern Jazz Quartet. The music was unbelievable-that's why I bought the trumpet-but also the visual thing was amazing because Miles on stage was like a big actor, like Marlon Brando on On the Waterfront. Then you had Lester Young with the saxophone kept almost horizontal, and with his hat-it was like a show.

Now in my projects the music can go wherever it wants, if the band feels like it. We can switch to a blues, increase the tempo, or take it completely out for half an hour; for me, it's cool. On a record, this doesn't really happen. It's a different rapport. Maybe you are in a booth and you can't really see each other. Sometimes when playing, it's really important to be able to see the smallest sign. For me, they are two separate arts. Live music is music, but it's also a show. I can remember the first time I saw Miles in '56 in Torino, my hometown. He was playing with [tenor saxophonist] Lester Young, then with some French musicians and then with the Modern Jazz Quartet. The music was unbelievable-that's why I bought the trumpet-but also the visual thing was amazing because Miles on stage was like a big actor, like Marlon Brando on On the Waterfront. Then you had Lester Young with the saxophone kept almost horizontal, and with his hat-it was like a show.A long solo live can be OK, but on the record it just becomes boring. You know, I am a big jazz buff and I have millions of records, and a couple of years ago I bought the box of the The Complete Jazz at the Philharmonic (Verve Music Group, 1998) live recordings. It's amazing, you can have [alto saxophonist] Charlie Parker playing with [tenor saxophonist] Coleman Hawkins and all these things, but after a while you can't stand it anymore. It becomes unlistenable because you can have [saxophonist] Paul Gonsalves playing 24 choruses, and then somebody else plays 24 choruses, and after three soloists you can't listen to it anymore, and besides that, you can't even remember what the fuck they are playing. Most of the tunes have the same chords; then the rhythm changes, but that's all [laughs]. Then, of course, you have Charlie Parker play an amazing short solo, but you have to be very patient. You might have to wait half an hour. I never listened to all the box. If it had been a DVD, it would have been great, but just the music is not enough.

AAJ: That's an interesting observation. Returning to Tribe, guitarist Giacomo Ancillotto leaves the faintest imprint on several tracks, but really shines on "F. Express" with a beautiful contribution. Were you not tempted to use him more?

ER: The thing with Giacomo is, he's totally unknown. I met him at my workshop in Siena the summer before last. I wanted to have the sound of a guitar-that electric sound, on a few tunes-so I called him. I love his solo on "F. Express." It was his first experience in a recording situation, with ECM and Manfred Eicher, and we only had two days to record, so I had to get what I could get. I didn't want that sound on all the record. He could have been more present, but that's the way it happened.

AAJ: His solo on "F. Express" is one of the most arresting solos on Tribe, and maybe it's a case of less is more. Hopefully we'll hear more from him in the near future.

ER: His solo is very kind of [guitarist] Bill Frisell, no? I like his solo because there are very few notes. Guitar players have the tendency to play a lot of notes.

AAJ: In 2011 you released another book called Incontri Con Musicisti Extraordinari (Feltrinelli, 2011), and in the preface Stefano Bollani says that you have the memory of an elephant. What are your memories of the gig in Argentina that resulted in The Forest and the Zoo (ESP, 1966) with Steve Lacy, bassist Johnny Dyani and drummer Louis Moholo-Moholo?

ER: Before that, the band was Aldo Romano and [bassist] Ken Carter, but Aldo left and went with Don Cherry, and Ken had to go back to the States, so Steve and I went to London to look for Johnny Dyani and Louis Moholo because we knew both of them. We had some gigs in Italy, and then we went to Argentina, where we had 15 days in a theater. We had a lot of people the first nights, but the music we were playing was not very friendly [laughs]. It was very radical, and so every day there were fewer and fewer people. The very last day, there was no one. We finished the gig, and we had no money, and we didn't know what we wanted to do. We didn't want to go back to Italy. We wanted to go to Rio de Janeiro, but we had to pay the ticket in dollars-because we were foreigners-which we had to buy on the black market, so it was very complicated. So we stayed one year in Buenos Aires. We played a lot, but we weren't making any money.

Then eventually, Alberto Ginastera-who was one of the greatest contemporary composers of Argentina and Director of the "Institute Di Tella-asked us to do a concert there and to record it. It was really our last concert in Buenos Aires, because Steve and I were going to New York-we asked money of friends and relatives for the ticket-and Johnny and Louis were going back to London. We did the concert and the record came out. For me, it was very good because there was a certain reaction to this record in Europe and Japan. All of a sudden, when I went to Europe I was known by the jazz community because of this record. I think it is a very good record and music of a historical moment.

AAJ: Where did you first come across Dyani and Moholo?

ER: I saw them perform in Antibes [1964] when they came to Europe with the Blue Notes and [pianist] Chris McGregor. Steve [Lacy] and I were very interested in them because they were very much into the free thing but with a different kind of accent. It was funny because Johnny's tribe was Xhosa, whilst Louis was a Zulu; they were like brothers, but every day they would kind of argue about their tribal shit [laughs], teasing each other. We were really together, and I was the third brother. We were always trying to bring the music somewhere else, towards a more improvised jazz kind of idea, whereas Steve was going more and more into a form of contemporary music. There were two different tendencies, and somehow it didn't gather.

AAJ: The Blue Notes were very influential on the London jazz scene in the mid-'60s, but strangely, all those guys died really young-trumpeter Mongezi Feza (32), tenor player Nikele Moyake (36), Johnny Dyani (41), Chris McGregor (54), and alto player Dudu Pukwana (52). Only Louis Moholo is still alive and playing-do you ever come across him?

AAJ: The Blue Notes were very influential on the London jazz scene in the mid-'60s, but strangely, all those guys died really young-trumpeter Mongezi Feza (32), tenor player Nikele Moyake (36), Johnny Dyani (41), Chris McGregor (54), and alto player Dudu Pukwana (52). Only Louis Moholo is still alive and playing-do you ever come across him?ER: I haven't seen Louis in a long time. Sometimes we say hello to each other through someone. The last time I saw him was maybe 20 years ago when I was in Milan and Louis was playing in Turin, about 120 kilometers away, and Louis had a heart attack. Somebody called me, so I got in my car and I drove to Turin. It was funny because I arrived outside visiting hours and they wouldn't let me in. I said, "Listen, I came from Milan; my African friend is alone and he asked for me. Please."

And they said, "Who is this guy?"

I said, "He's Louis Moholo."

"Ah, Louis! You are a friend of Louis! OK, come in!"

Louis was the king of the fucking hospital [laughs]. His wife, who was a professional nurse in London, was there, and she was telling everybody, "Don't do this" and "don't do that." He had his record player, and he was listening to records very loud [laughs], with all the heart-attack people in the ward dying.

The director of the hospital came and he was, like, "Hey Louis! How are you? I'm so glad to see you." He was really the true sensation of the hospital. I thought he was dying, but he was very good and never had any problems after that.

AAJ: Thanks for sharing that. Are there any plans for an English translation of this book?

ER: I would be very happy if somebody does it, because I like it very much. I think it's the best thing I ever did, better than my playing and everything. I wrote it myself, and I had a lot of fun writing it because I dug deep into my elephant memory.

< Previous

Alma

Comments

Tags

Enrico Rava

Interview

Ian Patterson

Stefano Bollani

Gianluca Petrella

Fabrizio Sferra

Giovanni Guidi

Gabriele Evangelista

John Abercrombie

Palle Danielsson

Jon Christensen

Franco D'Andrea

Dino Piana

Aldo Romano

Roswell Rudd

Steve Lacy

Massimo Urbani

Joe Henderson

Mark Turner

Clark Terry

Bob Brookmeyer

Conte Candoli

Frank Rosolino

Billy Higgins

Paul Motian

carla bley

Larry Grenadier

Jeff Ballard

Manfred Eicher

Arvo Part

Philip Glass

Stefano Battaglia

Gianluigi Trovesi

Lester Bowie

Keith Jarrett

Dino Saluzzi

Don Cherry

Gato Barbieri

Roberto Gatto

Paolo Fresu

Red Garland

Mal Waldron

Cecil Taylor

Marion Brown

evan parker

Rashied Ali

Eberhard Weber

Lester Young

Modern Jazz Quartet

Charlie Parker

Coleman Hawkins

Paul Gonsalves

Bill Frisell

Johnny Dyani

Louis Moholo

Ken Carter

Chris McGregor

Mongezi Feza

Dudu Pukwana

Bix Beiderbecke

Louis Armstrong

Chet Baker

Miles Davis

Gil Evans

Claude Thornhill

Joni Mitchell

Charles Mingus

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.