Home » Jazz Articles » Rhythm In Every Guise » Tony Reedus

Tony Reedus

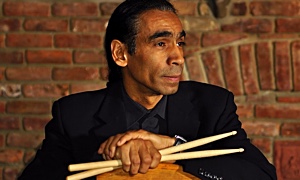

The decidedly assertive side of Reedus

Since he arrived in New York City in 1980 to take over the drum chair in Woody Shaw’s band, Tony Reedus has demonstrated the ability to shape the music of a variety of mainstream ensembles by executing variations in dynamics, touch, and degrees of activity. Treating the drum set as an instrument of kindred components, Reedus moves freely between the polarities of bold self-assertiveness and restrained support. He is capable of directing a band’s progress by employing hard, snapping accents, or convoluted fills that leave the listener in awe of his audacity. On the other hand, Reedus changes direction on a moment’s notice, plays inventively at low volume levels, and frequently allows the bassist to manage the music’s flow and the soloist to move about without undue interruption.

Since he arrived in New York City in 1980 to take over the drum chair in Woody Shaw’s band, Tony Reedus has demonstrated the ability to shape the music of a variety of mainstream ensembles by executing variations in dynamics, touch, and degrees of activity. Treating the drum set as an instrument of kindred components, Reedus moves freely between the polarities of bold self-assertiveness and restrained support. He is capable of directing a band’s progress by employing hard, snapping accents, or convoluted fills that leave the listener in awe of his audacity. On the other hand, Reedus changes direction on a moment’s notice, plays inventively at low volume levels, and frequently allows the bassist to manage the music’s flow and the soloist to move about without undue interruption.Although there’s a lot more to Reedus’ musicianship than a snippet from any single recording, the first seven seconds of “Passage” (Joe Magnarelli, Mr. Mags, Criss Cross) captures one essential aspect of his style: The distinctive, harmonious sound of his drums. The track begins with a rousing, eight-bar drum break that establishes a brisk tempo for Jim Snidero’s bebop-oriented composition. Because Reedus lays off of the cymbals, it’s an opportunity to hear his drums in their unvarnished glory. Each one possesses individual characteristics, yet they share a full, warm resonance that adds up to a unified, organic whole.

Reedus begins the break with brief, swinging patterns on the snare that resound with a kind of crisp thickness, yet each stroke dies quickly, allowing one stout, muffled thump of the bass drum to be clearly heard. Completing the first two-bar phrase, a couple of blunt blows to the floor tom-tom sound broad and substantial, but don’t ring too much. He begins a second two-bar phrase by returning to the snare with a variation of the opening figure, and again makes a pair of strokes, this time to the mounted tom-tom. The difference in timbre between the tom-toms invites attention, and the rhythmic similarity ties the phrases together. Building momentum in the final four bars, Reedus inserts a pushy, staccato eighth and quarter note combination, first to the snare and then to the low tom-tom. Underneath these driving cadences, he executes four hits to the bass drum that slightly throw things off balance because they don’t rigidly conform to the basic pulse. From beginning to end, it’s a great way to jump-start the track.

One of the overall strengths of Reedus’ playing is the ability to frame different compositions by utilizing a variety of rhythmic strategies. During the medium-tempo head of “Pocket Change” (Jim Snidero, Vertigo, Criss Cross), alongside bassist Peter Washington he creates a thickset foundation by playing pieces of quarter and eighth note triplets between the snare and bass drum. In the same instance, the ride cymbal moves from stating the pulse with pinging individual strokes, to light splashes that complement the chords of pianist David Hazeltine. Jim Snidero’s up-tempo, bebop line “A.S.A.P.” (Jim Snidero, Vertigo, Criss Cross) gets a sparse yet no less effective treatment. Reedus pointedly accents along with the melody on the bass and snare drums for the first two bars; then brings down the volume and nearly drops out completely, letting his ride cymbal do almost all of the work.

Reedus’ talent for guiding a band in a subtle manner is apparent on two tracks from Minor Thang, his impressive date as a leader released by the Criss Cross imprint. Playing under Richie Goods’ flexible bass line, during a delightfully relaxed version of Frank Strozier’s “Frank’s Tune,” he deftly combines ephemeral strokes on the ride cymbal, lightly snapping hits to the snare, as well as occasional mounted tom-tom and bass drum punctuation, all of which support the melody in exactly the right places. Then spare figures on the snare and mounted tom-tom hold together the composition’s wavering, seemingly out-of-tempo bridge. Reedus evinces reverence for “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat,” but his rendition tweaks the classic Charles Mingus ballad by taking it at a slightly faster tempo than customary, and using sticks rather than brushes. In synch with Goods, his ride cymbal dings clearly but not loudly. Snare drum inflections are all the more meaningful because he doles them out with care, providing texture and a slight jolt here and there without ever disturbing the piece’s somber disposition.

The decidedly assertive side of Reedus’ drumming is not simple or monolithic, but rather a consistently shifting palette of rhythms and emphasis. On “King Midas” (Walt Weiskopf, Anytown, Criss Cross), during tenor saxophonist Walt Weiskopf’s solo, he takes diverse positions within the music. Sometimes his comping is in step with, but not directly influenced by Weiskopf and pianist Renee Rosnes. In other instances, Reedus’ snare, bass and cymbal accentuation land smack on top of Rosnes’ chords. Or, he frequently takes something that Weiskopf plays and runs with it, banging out expansive, asymmetrical fills that shake things up. The title track from Minor Thang is another good example of Reedus’ way of pushing the music forward while still allowing for everything that’s going on around him. As his ride cymbal and Goods’ bass keep the band moving, toward the end of the third chorus of Ron Blake’s tenor saxophone solo, the drummer’s points of stress get harder and more insistent. The snare drum chomps vigorously in a not-quite-predictable pattern, and he adds weight by frequently placing single hits to the bass drum before and after the snare in a slightly lower volume. He responds to Blake’s seven-note phrase by playing a melodic-sounding volley to the two tom-toms, then immediately backs off when the saxophonist moves on to another sequence of ideas.

SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

Tony Reedus Quartet, Minor Thang (Criss Cross)

Joe Magnarelli Quintet, Mr. Mags (Criss Cross)

Walt Weiskopf Quintet, Anytown (Criss Cross)

Jim Snidero Quintet, Vertigo (Criss Cross)

David Hazeltine Quintet, Good-Hearted People (Criss Cross)

Tony Reedus, The Far Side (Evidence)

Benny Golson Quartet, Live (Dreyfus Jazz)

Benny Golson Quintet, Domingo (Dreyfus Jazz)

Steve Slagle, Our Sound! (Double-Time)

James Williams, Meets The Saxophone Masters (DIW/Columbia)

< Previous

Dub: Mixed Up and Mixed Down

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.