Home » Jazz Articles » SoCal Jazz » Steve Khan: A Rich Discography and A Priceless Left Hand

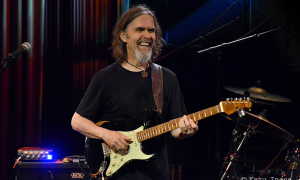

Steve Khan: A Rich Discography and A Priceless Left Hand

My music is a catalog of songs that I have loved all my life. It's the music I grew up with. Each song has a personal resonance, a place in my heart. Playing them becomes as easy as talking because I have a feeling for them.

—Steve Khan

The fusion turned Latin guitarist has recorded over twenty studio albums and appears on nearly one hundred more records with other jazz greats. Over the years Khan has played with Ron Carter, Steve Gadd, Anthony Jackson, John Patitucci, Jack DeJohnette, Randy Brecker, Michael Brecker, Dennis Chambers, David Sanborn, Bob James, Al Foster, Larry Coryell, Dave Weckl, and so many more giants of the industry.

The son of a legendary songwriter, Khan talks about how and why he changed things up and made it on his own. "I thought everyone had Frank Sinatra over for Sunday barbecue," Khan states, illustrating the unfazed reality of his Hollywood celebrity laced childhood. A bevy of often humorous and certainly life-defining moments are shared. In many ways, they are period pieces that open up a window to another place and time.

As we enter stage right, Khan is about to tell us about his career threatening hand affliction...

All About Jazz: Well, Steve, before we get too far into things, let's dive right into your latest release. You have been exploring the Latin sound for well over thirty years now. It would seem that you have peeled back yet another layer with Patchwork (Tone Center, 2019). This is, I believe, your fourth consecutive final album, right? (laughing)

Steve Khan: (laughing) Yeah, it might be the sixth. Actually, it is the fourth. Parting Shot (Tone Center, 2011), Subtext (Tone Center, 2014) Backlog (Tone Center, 2016), and now Patchwork are all really an extension of one piece of work. I was diagnosed with Dupuytren's Contracture. I wasn't in any pain, but still I didn't know for sure that I would be able to finish these records. I saw a little bump on my left hand and ended up going to a couple of hand specialists. They both confirmed the same diagnosis. The second doctor was more of an expert about this particular affliction. I knew they weren't in the prediction business, but I asked his opinion on whether or not I would be able to do the record. I even offered to sign a waiver of responsibility. I just wanted his professional opinion, not a guarantee. The doctor told me that based on what he saw that he thought that I would be able to do it.

AAJ: I'm not familiar with that affliction. What can you tell us about Dupuytren's Contracture?

SK: Basically, it will make it so that you can't open your hand anymore. Some people think it is trigger finger or something like that. It is not. I have information about it on my website (stevekhan.com) for anyone that wants to know more about it. It's kind of a hereditary thing. Not a lot is known about it. I could go the rest of my life with that little bump there and nothing ever happens. Or I could wake up tomorrow and my fingers are all closed-up and you can't open them.

AAJ: Interesting and scary at the same time. Hopefully you get lucky.

SH: Yeah, well, I don't know. I have noticed over the past few months that the bump has gotten a bit larger. I'm not in any pain or discomfort of any kind. But there is no doubt in my mind that it is bigger than what it was before. I just keep going. I'll worry about it when, or if, it happens. But even now, the mental toll is there. Anytime I feel anything I can't help but feel like, "Uh-ho, here we go. This is it." That's weighed heavily while working on these records. But back to the original question, I feel like we all just got better and better at doing this. Obviously, guys like Ruben Rodriguez, Bobby Allende, and Marc Quinones don't need to get better anyways. This is their music. They were born to do this. The rest of us grew along the road.

AAJ: Well, that makes a lot sense now that you say that. This is a quadrilogy of sorts that continues to grow and spread its wings. What can you tell us specifically about the latest addition, Patchwork? How do you choose the material?

SK: Well, that process has evolved. On the first record, Parting Shot I wrote seven of the ten compositions. As time went on, I wrote less and less and less. I didn't write anything on Backlog and just one song on Patchwork. I struggled to write one tune. All these records, and really through my entire recorded history, you will hear the music that inspired me to get better and try to do this. It's music from the mid-fifties through the early sixties. Blue Note, Atlantic, Riverside, all those records. The tunes I pick, from among these jazz standards, are ones that nobody else plays. Very few of them have been played beyond the original. The main thing is that each of those songs have to have some personal resonance, a place in my heart. Playing them becomes as easy as talking because I have a feeling for it. Interpreting them with Latin rhythms makes no difference to me. It is still the same music. Emotionally it feels the same to me.

AAJ: Well, I think you make that quite relatable to your core listener. I, for example, very much have a place for Bobby Hutcherson's "Bouquet." It's such a beautiful and truly unique song. I never thought anyone would or could do that. Yet, your reinvention is stunning. I understand now that your love and affinity for "Bouquet" truly resonates.

SK: Thanks Jim. Well, you know it's funny too that I had recorded it once before many years ago. In 1975 Larry Coryell and I went out as an acoustic contemporary jazz guitar duo. I was in charge of picking all the music we were going to play. One of the songs we played was "Bouquet." It's on the album Two for the Road (Novus, 1977). I was not happy with how that particular version came out. This now is my way of expressing my love for that piece and that album. On Backlog there are two songs from that album, Happenings (Blue Note, 1966). "Head Start" and "Rojo" are both from that record.

AAJ: That's nearly forty-five years of honing your craft between recordings of "Bouquet."

SK: Yes, sometimes you can love something at another point in your life, but it doesn't mean that you are ready to play it or express it properly. The interpretations of all the songs on those four records come from a better place within myself where I felt ready to do them. Twenty years ago, maybe not. This just felt like the right moment.

AAJ: You have broadened and expanded your Latin sound over a sea of high-end albums over the years, many more than the four we have referenced. Do you feel that Latin music has infinite levels of depth to uncover?

SK: Yes, it is infinite. I get deeper and deeper with it the further we go. If some fictitious offer was on the table to keep doing another record every eighteen months and to do whatever I wanted, I would keep exploring this. This rhythmical approach to the same music that I have always loved puts me, essentially, all alone. I am the only Latin jazz guitarist with the full complement of percussion. There can be Latin jazz with just a conga or a drum set. I'm doing it with the full complement of timbales, guiro, congas, percussion menor, hand percussion, bongos, maracas, and everything else. I feel very comfortable in this place, because I am there by myself.

AAJ: Flashing back to the beginning, I have to be honest with you, Steve, that only recently did I learn that your father was legendary songwriter Sammy Cahn. With the different spellings of the last names, I never made that connection. How did that spelling change evolve?

SK: That's kind of a funny story. My father grew up in the early 1900's on the lower east side of New York. Like many other Jewish people, he was trying to assimilate into the culture. I didn't know until I was well into my twenties that my father was born Sammy Cohen. My father, the family, was very poor back then. As poor as poor can be. When he was fifteen years old, without having graduated high school, dad went off to play his violin with a band in the Catskills. Somehow from there he ended up going to Los Angeles looking to have a career as a songwriter, as a lyricist. He opted to change his name for his career and was going to go with Kahn, However, there was already a successful lyricist at that time named Gus Kahn. So, dad went with Cahn. When I entered the world in 1947, I was Steve Cahn. That's how I grew up. Years later, when I first started having my name on records, the spelling was all over the place, Not by my design. Kahan, Kahn, Cohn, every combination you could think of all due to error. When I moved to New York, I still spelled it Cahn. I had never changed it. But it kept happening. So, I decided to pick one that I thought was the most interesting, that being Khan. Later I realized, psychologically, I was trying to separate myself from my famous father so that people wouldn't think that I was Sammy's son. I didn't want people to ever think that Steve got that job because his father got it for him. I wanted to rise or fall based on my own talents, if I had any.

AAJ: Yeah, I figured part of it was wanting to make it on your own merit.

SK: Yes, absolutely that was part of it. The other part, since I frankly had a difficult relationship with my dad, it was a way of just saying, "Fuck you dad." So that's the story, and after all these years people still spell it wrong (laughing).

AAJ: (laughing) Difficulties with your dad, but what was that like growing up with Frank Sinatra and other big stars being part of the ordinary?

SK: Here is my best perspective on that. When I first moved to New York in 1970, I had a very small apartment and one night I was watching the Tonight Show. Rob Reiner, the actor famous from All in the Family and other things, was a guest that night. He was, of course, the son of Carl Reiner, a brilliant writer, comedian, and actor. So, like myself the son of someone famous. Johnny Carson asks Rob a very similar question that you just asked me, what was it like growing up with a famous father. Rob said that he never thought it was much of a big deal and figured everyone had Mel Brooks over for dinner.

AAJ: (laughing) That's great. That had to hit home.

SK: Yeah of course, I laughed too. But Jesus. That was it. I felt exactly the same way. I thought everybody had Frank Sinatra and all these other amazing people over for Sunday barbecue. It was a while before I realized that not everybody has this going on. We didn't go to fancy private schools or any of that. The best thing my parents ever did for me was to put my sister Laurie and I into public school. It was fantastic. A public school's education in the fifties was great. There were two other people that also came out of University High School in West Los Angeles that were in my sister's grade, two years younger than me, that grew up the same way. One being Jeff Bridges, the son of famous actor Lloyd Bridges and Bonnie Raitt, son of Broadway singer John Raitt.

AAJ: They lived very much the same life.

SK: The same thing, The same high school. There is a bond between the three of us that is sort of unbreakable because we understand something that is there that just comes with the territory.

AAJ: What else did you have to compare it to? Makes sense that it would become the norm for you, and as you say, for other children of a famous parent.

SK: Yeah, one day I was home, and a friend came over. All I wanted to do was to shoot some baskets or toss a baseball around like most kids back then. My friend goes into the house to use the bathroom. He comes back out and his mouth is gaping open. He says to me, "Oh my God, do you know who is in your living room?" I said no. He excitedly says, "Dean Martin." I was like, "Yeah, so what? Let's play catch." It took me a while to realize the significance of them seeing people in our living room that they had seen at the movies or on television.

AAJ: Also, at home you started on the piano. Because it was there, because of your dad, or?

SK: My father wanted me to be everything he never had the chance to be. Again, he grew up poor. Now he wanted me to be a lawyer. Of course, to start with, he wanted me to graduate from high school and graduate from college. Fortunately, I ended up doing that. In addition to that, he wanted me to be the musician that he never had the chance to become, even though he had huge success as a lyricist. He shoved me in front of the piano when I was five years old. I played until I was twelve. I really hated it. I wasn't really learning anything. My whole goal was to get through the lesson without getting rapped on the hand with a ruler for not playing something correctly. What I learned to be was a great mimic. I would cajole my teacher into playing it one more time so that I could watch her play. Then I could just play it by copying her, not from learning it. I wasn't reading the music. I just didn't want to do it. At twelve, I finally told my dad that I didn't want to do it anymore and that I wanted to play sports. He was crushed and angry. But that was the end of the piano for me.

AAJ: Yeah, you wanted to be out playing ball. As you alluded to earlier, we all did back then.

SK: I always thought that I was going to be a baseball player.

AAJ: You and me both! I guess a few million other kids too. After that, you somehow ended up playing drums in a surf rock band.

SK: The Beatles hit the scene in the early sixties. Suddenly, all my friends wanted to play guitars and be in a band. I wanted to be in the band with my friends. I saw what they had and didn't have. Drums. They don't have drums. That's looks easy, I can do that. What an idiot I was to think that at the time, but, anyway, I asked my dad about getting some drums. He was in recording studios a lot and I thought maybe he could throw together a drum set from spare parts from all his famous musician friends. He said to me, "I'll do that for you, but only if you take lessons." I rolled my eyes, thinking here we go with lessons again. I had no choice, so I agreed to take lessons. This is where the story gets interesting in retrospect of the big view of my musical life. I'm driven out to a little studio in the San Fernando Valley. There are a bunch of little rooms for guitar lessons, bass lessons, etc. I'm all excited to walk into a room and start smashing around on a drum set. The only thing in the room is a little woodblock with a piece of rubber in the middle of it and a couple of chairs. The teacher walks in and introduces himself and I ask him, "Where are the drums?" He says, "Oh, we're a long ways away from that." Rudiments, fundamentals, and stick control all had to come first. Again, I am rolling my eyes. I told the teacher, "But I want to play, I want to bash, I want to hit things." I never got it. That was the end of that. But somehow, I was good enough to keep time, and I was in a band with my friends. DK and The Cavities, with my friend Dan Keller, was that first band. This band was kind of goofy. We had three guitarists, no bass, drums, and a lead vocalist.

AAJ: You took what you had amongst your friends and you made a band out of it.

SK: Yeah, it was fun. I started going out to see other bands. Remember, this is Southern California and surf bands were very popular at the time. I went to see The Chantays, who had a hit song called "Pipeline." I was like a groupie following them around. They were also playing other stuff, like the great Freddie King instrumentals. I became fascinated with that. The two guitarists in that band, Bob Spickard in particular, turned me on to everything. Freddie King leads to B.B. King, etc. Then he played me my first Wes Montgomery record. I was maybe sixteen or seventeen. This opened the door to the guitarist I am now. It sounds like I am making this shit up, but a surf guitarist turned me on to Wes Montgomery...

AAJ: ...and that changed your life.

SK: Yes, and it takes me to the follow up on the woodblock story. Years later, after I have gone to New York City, I'm in a studio with Steve Gadd. He arrived on the New York scene about the same time I did, out of Rochester. We are all sitting around waiting for Steve's drums to arrive, with nothing to do except wait. There is just a snare drum sitting there. All of a sudden, Steve sat down and started playing this snare drum. I sat there mesmerized. I never saw someone sit there and make so much music out of just a snare drum. Suddenly, this giant light bulb goes off in my head.

AAJ: Ah, back to the teacher.

SK: Exactly, Jim. Back to the teacher in the studio with the little woodblock. I finally realized what the teacher was talking about. Here was the realization of all those rudiments and fundamentals that I didn't grasp at the time. I never looked at it the same after that. It was one of those moments that I just got it, and it all came flooding in.

AAJ: All about timing, just like "Bouquet," and so many other things.

SK: I always find it fascinating to look at the learning process. You can go back and realize that this teacher or that teacher wasn't really a jerk or whatever like that. It's none of that. It's that you, as the student, weren't ready to receive what he was trying to give you.

AAJ: Again, it was timing, being in the right place at the right time, that led to you playing with the Chantays, yes?

SK: Yes, their drummer, Bob Welch (not the musician of the same name that played for Fleetwood Mac), quit the band for some reason and they were stuck. I couldn't do any of the stuff that Welch was doing. Why they asked me, I will never know. The next thing you know, I'm on tour with the band. I'm still a kid in high school. I got a taste of what it's like to be on the road. We were mostly driving long distances, playing ballrooms, and other venues like that. It was my first experience with travel and having my own money. The first thing I bought was my first stereo system. You and I were talking the other day about having components. I bought a turntable, some kind of integrated amp, and custom-made speakers. It was a big deal to have my own stereo in my own room.

AAJ: Yeah, it sure was. Like we were saying the other day, putting cool components together is now a lost art. I quote Peter Erskine in saying, "If you are listening on those silly little earbuds, then you are really cheating yourself."

SK: A while back, I was sitting behind a young woman with earbuds. Her friend got off at the next stop and she handed her one of the buds. I asked her how she could listen to music like that (now reduced to only one bud). She said, "Oh, it's not a problem, we do it all the time." I couldn't believe it.

AAJ: Man, I don't know whether to laugh or cry. But getting back to real listening and the excitement of having your own stereo in your room.

SK: Yeah, I started listening to so much music. So much, it was unbelievable.

AAJ: Including a lot of Montgomery, I'm sure, and then on to starting to play the guitar at age nineteen.

SK: Yes, as you know, the path is long when it comes to hearing new music. You are listening to something you like, and you decide to check out the drummer on that record and other stuff he has done. Then you check out something by the bassist on that album, etc. Back in those days an LP was two dollars. So, if I had twenty dollars, I could buy ten records. I would ride my bike over to Westwood Village and buy ten records at a time. How cool was that? I bought Wes Montgomery's Movin' Wes (Verve, 1964) album. I had forgotten that one of the many albums that Bob Spickard had played for me was by Montgomery. It was Boss Guitar (Riverside, 1963), which later ended up being my favorite Montgomery album of all time. But at the time the only reason I purchased Movin' West was that the cover showed him kind of walking and playing a Gibson ES-125. The same guitar that BB King was playing on one of his album covers. So, I figured this guy has got to be pretty good. I had no idea! When I turned up the volume on Wes playing "Caravan," it was like it was shot out of a cannon. More than that, I'm listening to Grady Tate. I said to myself, "Oh my God that's what being a musician, a drummer is all about. I went into the room where my drums were and sat down and realized that I couldn't play. Who was going to hire me? If excellence is what I hear Grady Tate doing I'm not even in the same area code. I put down the sticks and I never played again. Over the next few weeks, I came to the conclusion that I wanted to sound like Wes Montgomery.

AAJ: High aspirations for a guy that as yet hadn't started playing the guitar.

SK: Yeah, well I just started immersing myself in it. I graduated high school and was going to UCLA. I was a psychology major. I really thought that I was going to solve all the problems of the world. That I was going to fix people. I was slowly picking up the guitar at that time. I changed my major to music. I saw all these classes that were like, beginning harmony, beginning theory, beginning everything. I figured I was a beginner, so I signed up for these classes. What I didn't realize as I walked into these classes as a sophomore was that I was in a classroom with people the same age as me but they had all been playing classical music since they were five years old. Whether it was the piano, the violin, the cello, the viola, the clarinet, the trumpet, or whatever it was. At the time UCLA didn't recognize the guitar as an instrument. So, I couldn't get instruction at UCLA. I started to freak out because all these people already knew everything, and I didn't know anything. I had to study with this woman that saved my life. I studied piano and theory with her or I never would have made it. In the process of all that I started meeting musicians. I was invited to these jam sessions that I look back on now and wonder why or how I ever got invited when I could hardly play. For some reason, these players liked me, and it led to meeting some really great musicians that were way above where I was. Two of the musicians I met was a pianist named Clarence McDonald and drummer Michael Carvin. They had just gotten back from Vietnam. Their life perspective was on a life and death level that I had never been close to. Not to mention all kinds of racism and horrible shit that sadly is still going on in this country today. But Michael and Clarence became very good friends of mine. Clarence had become the musical director for the Friends of Distinction. They were just starting up as group and later became famous for the hit record "Grazing in The Grass."

AAJ: Right, yeah. That was a huge hit. I can dig it.

SK: They had studio musicians on the record, but I toured with the Friends of Distinction. I was with Clarence at a jam session one day and he gets a call from Phil Moore Jr. in regard to making a record for Atlantic. He could hear me noodling around on his end of the phone and asked who it was that was noodling on the guitar. Clarence tells him that it's this kid named Steve. Phil says, "Well tell him to come to our rehearsal tomorrow." Next thing you know I am walking into this rehearsal and I see Stix Hooper on drums and Wilton Felder on bass.

AAJ: Wow, the Crusaders. That had to be mind boggling.

SK: You got to remember, Jim, I had just started playing. Now I am in the same room with them. I idolized the Crusaders. I almost fell over from a heart attack. I couldn't believe it. I tried to be cool about, but are you kidding me? Anyways, I got through the album. I was really lucky. I was very inexperienced. I'm still not sure what they heard in me.

AAJ: That timing thing again. But also, as you said, they liked you. That has something to do with it. I've had many musicians tell me how important it is to get along and have a good chemistry together.

SK: Maybe so. After that, Wilton Felder asked me to play on another record of his.

AAJ: Some other opportunities came long, but ultimately you went to New York to chase the dream.

SK: I first went there in 1968 to visit my dad. He had an old and dear friend named Stanley Krell that was a drummer and percussionist in the classical sense of the word. He was playing in several Broadway shows. So, I went with Stanley one day when he was playing in the pit on Cabaret. This was the Cabaret that Liza Minnelli was in. My dad had to kind of talk me into going, saying that I should go see what real musicians do. I begrudgingly went, and Uncle Stanley tells me that I have to be very quiet and that they don't let very many people sit down here. He was playing percussion at a matinee, which meant timpani, the occasional snare drum roll, and some other stuff. It was very cramped down there, you kind of had to squeeze between the music stands. My first impression of what this life was like is that I look at the music stands, and I see all these Swedish porn magazines.

AAJ: (laughing) That I wasn't expecting.

SK: Me neither (laughing), I don't think I had ever seen porn magazines before. I had seen my father's Playboys, but that's not quite the same thing. So, I'm wondering what the hell I have walked into. But then the musicians start to roll in when the show is about to start. I look over to my right and I see Art Farmer subbing on third trumpet.

AAJ: Wow, likely a bigger surprise than the porn.

SK: Oh my God, "Stanley, Stanley, do you see who that is," I said excitedly. Stanley says "Yeah, Art Farmer, he subs here once in a while." He says it like it's no big deal. "But, but, that's the Art Farmer that makes the quartet records with Jim Hall," I responded still in disbelief. He was one of my idols. How could this be? It was just completely incongruous to me at the time. One of the greatest jazz musicians has this secret life playing in the pit on a Broadway show. So, then I go back to UCLA and my father calls me and tells me that one of Stanley's former students, a vibe player, is coming into Los Angeles. They thought we should meet, that we would have some things in common. He was playing with folk singer Tim Buckley at the Troubadour. I said sure and then there was the moment that changed my life. I met vibraphonist David Freidman, one of the greatest musicians I ever met in my like. They were playing this really progressive folk music, with Johnny Miller on bass. They were introducing elements of jazz into what was basically folk music. This was an incredible time in our culture. The late sixties had a lot of experimenting and the boundaries between genres were melting. Everything was fusing with this and that. The Beatles, of course, paved the way for all of that. I got together with David and Johnny and we were jamming while they were making a record at Elektra Studios called Happy Sad (Elektra, 1969). The next thing I know, David is inviting me back to New York to play on a quintet record. They had a summer long gig and were renting a house. It was great. When David started taking me around New York, I realized that if I am ever going to see if I am good enough to do this I have to move here. I'm not the most adventurous person in the world, so it wasn't an easy thing to do. Plus, I still needed another quarter to graduate from UCLA. Moving here was one of the most courageous things I ever did in my life because it is so completely out of character for me. David was already doing very well in the music business. He took me along to do some jingles he was contracted to do. The night before, I remember it like it was yesterday, we went to see the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra at the Village Vanguard.

AAJ: That had to be incredible.

SK: It was an incredible night because I was expecting to see Sir Roland Hanna on piano and Richard Davis on bass. Instead I see Chick Corea and Miroslav Vitous playing with the Thad Lewis/Mel Jones Orchestra. I wanted to die. I couldn't believe this was happening. Chick had already done Now He Sings/Now He Sobs (Solid State, 1968) at that point. I was thinking to myself that this was something that I would never see happen in L.A. The next day we are off to the jingles session and who do I see on flugelhorn? Thad Jones. This can't be, how can this be? But there he was in the first room that we walked into. It just didn't compute that these amazing jazz musicians would be playing something for toothpaste the next day.

AAJ: At the time, I'm sure that was a mind-boggling reality check.

SK: Out of another room someone comes out in a dead panic because their guitarist didn't show up. He says, "Oh my God, what are we going to do now?" A very talented guitarist by the name of Billy Mure happened to be there. He went in and recorded the jingle and fifteen minutes later it was done. I just couldn't believe what an incredible place this was and everything that was going on. Then, I'm standing in the lobby of these four studios and I hear some music coming out of another room. I ask David who was in there. He says, "Oh, that's Chico Hamilton, he's producing a jingle."

AAJ: Oh man, your head must have been spinning.

SK: Jim, I was just dumbstruck by all of this. In that one moment, I knew that I had to be there. I had to be in New York. I owe all of that to David Friedman and Johnny Miller. They opened the door to this life and somehow gave me the courage to move here.

AAJ: After you moved, how did your career develop? I know you got in with the Brecker Brothers in the early seventies.

SK: Yeah, I arrived in January of 1970 and Randy had already been here for a little while. He came directly over from the University of Indiana where he was studying with David Baker. I don't recall exactly how I met Randy and Michael, but we were all just getting started. I had put a band together that wasn't really very good, but somehow, I had the nerve to ask Randy and Michael if they would join the band. Fortunately, they did, and of course they had the ability to take some less than ordinary music and make it actually sound like something. We all became friends. There were a few of us that all arrived around the same time. A few left because maybe they weren't quite good enough or whatever, but the rest of us helped each other and all became friends.

AAJ: That doesn't surprise me that you had a built-in support system like that. Most musicians, perhaps in particular jazz musicians, have a respectful lean towards being helpful to their brethren as opposed to being competitive. Who else were among those arrivals in the early fusion years?

SK: I met John Abercrombie at that time. Ralph Towner was here. I already knew Larry Coryell from before. Larry and John McLaughlin were first level fusion guys. The rest of us were trying to find our way. At that time, the great Dave Liebman started this organization to help us young guys that had a lot of ideas, but nobody wanted to hear us. It was called Free Life Communication. It was a place for musicians of our ilk to talk, to have jam sessions, to put on concerts, to exchange ideas, both musically and intellectually. It would start out with someone saying that they read an interesting book that week. Then we would talk about the book. All of this fostered some amazing conversations and incredible jam sessions. This was what we called the loft scene back then. You, obviously, couldn't be jamming with drums in an apartment. So, guys started renting these empty spaces. They would have someone make a bathroom and a kitchen. Other than that, it was just raw space and you could play all night. In the midst of all that time together, we became much better musicians. Then too, the deepening of our friendships. That group of people expanded to include Don Grolnick, Will Lee, and several others.

< Previous

Whadeva (Live at Dangerous Art Studio...

Next >

Django-shift

Comments

Tags

SoCal Jazz

Steve Khan

Jim Worsley

Ron Carter

Steve Gadd

Anthony Jackson

John Patitucci

Jack DeJohnette

randy brecker

Michael Brecker

Dennis Chambers

David Sanborn

Bob James

Al Foster

Larry Coryell

Dave Weckl

frank sinatra

Ruben Rodriguez

Bobby Allende

Marc Quiñones

Bobby Hutcherson

Sammy Cahn

Bonnie Raitt

The Beatles

Freddie King

BB King

Wes Montgomery

Peter Erskine

Grady Tate

Clarence McDonald

Michael Carvin

Styx Hooper

Wilton Felder

Crusaders

Art Farmer

Jim Hall

Tim Buckley

David Freidman

Mel Lewis

Sir Roland Hanna

Richard Davis

Chick Corea

Miroslav Vitous

Billy Mure

Chico Hamilton

Brecker Brothers

David Baker

John Abercrombie

Ralph Towner

john mclaughlin

Don Grolnick

Will Lee

Jimmy Smith

Weather Report

Mahavishnu Orchestra

Return To Forever

Clive Davis

Ralph McDonald

Mike Mainieri

Warren Bernhardt

Marcus Miller

Omar Hakim

Wayne Shorter

Lee Morgan's "Melancholee," {{Joe Zawinul

Horace Silver

Manolo Badrena

Steve Jordan

Eyewitness

Steve Marcus

Eleventh House

Jay Anderson

Ben Perowsky

Joel Rosenblatt

Mike Stern

Nat King Cole

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.