Home » Jazz Articles » Talking 2 Musicians » Ronny Jordan: A pioneer of Acid Jazz, a Staple of Smooth Jazz

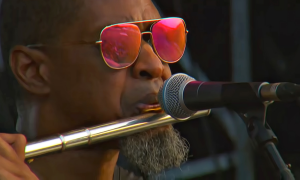

Ronny Jordan: A pioneer of Acid Jazz, a Staple of Smooth Jazz

A fan told me the other day, 'Ronny your music is timeless.' I take great pride in that, and I like to think of my music as timeless.

Ronny Jordan was a winner of Gibson Guitar's award for Best Jazz Guitarist, he was nominated for a Grammy, and was a jazz artist who has made it to the pop charts. He's known as one of the earliest and most successful jazz artists to draw upon the energy and vitality of hip hop. His music is perhaps best described as Urban Jazz, a blend of jazz, hip hop,smooth jazz and R&B—but certainly not limited to that.

His message is positive and spiritually uplifting, his grooves are addictive, and his playing is ingenious. He was completely self-taught, and in addition to his musicianship, he was an accomplished producer, arranger, and composer. He uses the studio as creatively as possible, and on his last album he introduced his fans to midi guitar—doing string, keyboard, and bass parts on a midi guitar.

Ronny was born and raised in London, the son of a Pentecostal preacher with a very interesting life story which he shared in this interview. This wide-ranging interview took place in late January of 2013, Ronny talks about the awakening of his talent, his early career, his big break with Island Records, and his recordings. Gifted, creative, and humble—he was all-about-the-music.

All About Jazz: I wanted to say thanks for taking time out to talk with us today. I really appreciate it.

Ronny Jordan: Look, I should thank you for considering me with all the many artists who are out there, I appreciate it.

AAJ: Oh no, I wanted to say for myself and on behalf of a lot of fans Ronny, thanks for all the hours and hours of pleasure your music has given us. I really appreciate all the hard work and dedication that went into making that music.

RJ: Well you know, honestly, I don't take credit for that. I give all credit to the Almighty, the Creator, because without Him we're nothing. And so, I can't thank you enough for the appreciation, it's just that I think it behooves every artist to keep his temple pure so that they can continually get inspiration.

Once we start thinking that it's just us—that we came up with all the inspiration and the ideas, that's when it starts getting self indulgent, and you won't be feeling what I'm doing. So I tend to give all praise and credit to the Most High.

AAJ: That's perhaps not a very common thing, but you certainly encounter that with a lot of musicians, going from people like John Coltrane all the way to people like Carlos Santana—they see themselves kind of like a vessel.

RJ: Absolutely, no question about that. You know, I could not have done that all by myself. So this is why it behooves us to keep all the egos out of it. When I think about it, it didn't start with me, it started with the Most High, and He chose me to share this gift with you. And that's just how I always look at it, and how I always will.

AAJ: It pays off to look at it that way, because when you look at it that way, you're all about the music.

RJ: Absolutely, I'm just all about the music, and sharing it. Everywhere I go to perform there is always someone who's touched, and I love that! That what I'm here for. I don't look at it as if it's all for me, no.

AAJ: Let me tell you about the first time I heard you in 1992. I was in Munich walking around the big pedestrian zone and they had this huge record shop, World of Music, with hundreds of headphones hanging around, and each headphone was a different CD—the way it used to be back in the day.

And sure enough I went to the section where they had guitarists like Hiram Bullock and those kind of guys, and I saw your album The Antidote was there. But not just one, there were three copies and people were still standing in line to listen to it.

RJ: Whao

AAJ: So I got in line, and I'll never forget it Ronny, when the music started, the opening bass lines on "Get To Grips" I thought like wow, and then the vibes came in—I was hooked right away.

I don't have all your albums, somehow I managed to miss Off the Record but I do have 8 of your albums, and I've never been disappointed, so I wanted you to know that.

RJ: (Laughing) Oh thank you! You know, Off the Record is a really funky album, it's probably the funkiest album of all my albums. But then again so is my upcoming album Straight Up Street which is kind of like a nod to the past, because it sort of reminds me of an updated answer to The Antidote

AAJ: I thought stylistically your last two albums were kind of intriguing, because one was like tip of the hat to the past and what brought you to where you are, and your latest album is like a trip to the future, it's a side of Ronny Jordan we haven't yet seen. But before we get to those two, which draw things together really well, maybe we can first explore the road that brought you to where you are now.

I've read that your father was a preacher, and your early musical influences were from gospel music.

RJ: From gospel and from my late father, God rest his soul. He owned an acoustic guitar and he only knew three chords. You know he was working too, and he used to come from work tired from 12 hour shifts and what have you, so he would just sit back and strum those three chords. (Laughing) A lot of times he would just fall asleep with the guitar, and I would watch him.

Of course back then the guitar was too big for me—this was back in the mid 60s, I was 3 going on 4, and on my 4th birthday my late father purchased a ukulele, like a small guitar, for me—this would have been November 1966.

AAJ: So a ukulele, that's basically like the bottom four strings of a guitar, is that right?

RJ: Yes, that's right. So essentially that was my first guitar, and my father bought me that in November of 1966 when I was four years old. So I'm self taught. I never went to music school. This is a gift from God. I can't read music—I don't know what half the chords I'm playing are. I mean I know the basic majors, it goes from A, B, C, D, E, F, G—so I know the major and minor chords, but all the other chords, I know a few of them, but I don't really know the names of the chords.

I was going to be sent to music school back in the 70s. The teachers at my school were aware of my talent, but one teacher, he was a Scottish gentleman by the name of Mr. Mackey, he was also a guitarist, he said no, don't send him. They were talking to my parents about this and they also said no, because in the end they all said it would change my style—and even by then my style was already unique. If I went to the school it would take it away, so they decided not to send me away.

AAJ: At what age would you have been when this was going on?

RJ: I was about 8 or 9 because my late mother was still alive, so this would have been the early 70s.

AAJ: So that early they recognized your talent.

RJ: Yes, by then I was already playing in church. I have this unique fingering style, so Mr. Mackey, my school teacher, he recognized this would change my style completely, and I wouldn't be who I am, I wouldn't be the same. So in the end they decided not to send me to music school. And Mr. Mackey wherever he is, God bless him.

AAJ: That was really insightful of him.

RJ: Yeah, because when I started playing his jaw dropped. (Laughing) I was like a celebrity at the school. I was like a pop star, I was mobbed!

AAJ: That kind of innate talent is something that really fascinates me. I read something that an academic wrote, I think it was a professor, and he maintained that great musicians are trained not born. And I've had the good fortune to interview some pretty great musicians and most of them were like you. When the right instrument dropped into their hands they went from zero to 80% really quickly, but it's the last 20%, I guess you could call it cutting and polishing the diamond, that's the hard part.

RJ: That's right, yeah, and part of being a musician is being able to write. Because you can have all the ability, but you've got to be able to write your own music, because then your voice will come through. So fortunately for me, you know, I didn't go to school for that either, I just listened to a lot of music. I discovered jazz at thirteen, but I didn't start playing it until I was 21. So during those eight years I listened to a lot of music, so I learned what to do, and what not to do. So that's really how I came up.

AAJ: Excuse my ignorance on this, but gospel music in America in the black churches is a very distinct form of music. You grew up in the UK, in London, is the gospel church there similar, or where you playing a completely different kind of thing?

RJ: No, it's pretty much the same, Pentecostal, that was our church, so the music was pretty much the same.

AAJ: So they would have been buying records from gospel groups in America and emulating them?

RJ: Yeah that's pretty much the same with jazz musicians in the UK, we would listen to a lot of American, and European jazz musicians, and then sort of form our own thing. Because you can never be the same as the next artist. You start with that artist, and somewhere along the way you develop your own style and find your own voice.

AAJ: You must have been in your late 20s when The Antidote album came out, and it made such a splash. You know Ronny, I used to think of you as an overnight sensation, but that can't be true. (Ronny is laughing) You probably paid some dues, so I was wondering, could you sketch your musical life? Like from your late teens until you landed the record deal with Island Records.

RJ: Absolutely, I'm happy to do that. Okay, I left high school in 1979 and I enrolled in college. My dear late mother had passed away in 1976, and I'm the second oldest child in my family. So in '79 the wounds were still fresh, we were mourning our dear late mother, she was only 40 years old when she passed. There were seven of us, so what happened was, my oldest brother left home, so I was the eldest child at home. So I went college for a year, a business studies course, and I passed. It was a general diploma, and I qualified for a national diploma and that was two years, whereas a general diploma was for one year.

So when I was about to do my national diploma my late father decided that I should work. He was made redundant and the rest of my siblings were all at school. I had to work, I had to get a job, so I did, this was back in 1980. By then I had gone to my first recording session, and I loved it. I started harboring dreams of becoming a full time musician. So from '80 to '85 I was working—my last job was for the police in London. Things started to get crazy, because by now I was starting to do a lot more session work. I was burning the candle at both ends, so I knew that at some point I would have to decide if I was going to do music full time, I knew I couldn't keep going the way I was, because I love music and I wanted to make a career out of it—and hopefully someday sign a deal.

So I had been working for the police from 1982 until 1985, and when I would leave that job, I would go and do recording sessions. Anyway, I had a chance to become a cop, and right down the road was the national training center for cadets, and they were ready to send me there because they needed more ethnic minorities. In my office the cops would come by, and they would stand me up and put their helmets on my head, and their jackets on me, and say, "You look really good in a uniform." And I thought they were joking until one day the chief superintendent, the highest ranking officer in the whole building, he called me in his office and said, "We're serious, we'd like you to be a policeman."

All the other black policemen in the office would speak to me privately and encourage me to join, saying it would be good for me. But I wanted to do music, so I had two choices, and in the end I decided to do music. I left in August of 1985, and the superintendent told me, "Look, if it doesn't work out for you, come back and be a cop." I told him I would. (laughing) This was 28 years ago.

So I went into music full time and became a pro in 1985. What helped me was a session I did with a great guitarist, it's sad because he's no longer with us. Are you familiar with Grace Jones?

AAJ: Yes I remember Grace Jones—she was like 6 feet something and had that squared off haircut.

RJ: She had a big hit record, "Slave to the Rhythm" and he played on that. He was the first serious pro I ever met, his name was JJ Belle. JJ performed for a lot of groups, you've heard his playing because he was everywhere. He inspired me because he told me I'd be a better guitarist if I went full time because I could practice, and I would improve a lot more. I loved that, and besides, I wanted to travel the world. So I went pro, much to the annoyance of my late father. (Laughing)

I mean we always got along really well, I love and respect him, he passed away almost eleven years ago now. That was just the one time we didn't agree. Well anyway, I went pro, and work was slow. But prior to that, going back to 1981, back then I was at a club, I wasn't inside, but outside you could hear the music coming out. So I would talk to the bouncers, but what was amazing to me was when I heard this hip hop beat. This was about 2am or 3am in the morning, so I hear this hip hop beat, and I hear some jazz guitar, but you could tell it wasn't on the same record, it was the DJ. He was spinning both sounds together, and it sounded amazing, just amazing. He made it fit, you know it might have been have been some Kenny Burrell or Grant Green. It wasn't Wes Montgomery and it wasn't George Benson, it was more like Kenny or Grant, and it was really hip. That's when the idea came to me, and I realized this is where I should go (musically.)

So in the early '80s I was in a lot of bands and doing gospel projects, because I was still in the church. But I was in some other bands as well. The whole jazz hip hop thing was a side thing for me back then. So being in all these bands, there was a lot of politics, and you know me, I'm all about the music, I'm not about the politics. So anyway, what happened was right about 1989 or 1990 I left the band thing and started to develop this hip hop jazz thing.

I realized I would need to dumb it down if this was going to make it on the radio—I'd have to lighten it a bit. So that is when *The Antidote was born.

AAJ: How did you get the deal, did you have it worked out in your mind what you needed to do?

RJ: I'd sent demos to all the labels in London and they all turned me down, basically saying what you have here is nice, but there's no market for it. So what happened was, I was doing a gig with a singer, and while I was backstage I was talking to this guy from Island Records and we struck up a very interesting conversation and he never forgot me, and at the time he was working for the studio. So a few years went by, and back then the straight ahead jazz thing had sort of made a comeback, so what I did was to get some friends and we went into the studio to do some straight ahead stuff.

So I sent that to the label. I called them and it was the same guy I'd talked to before, because when I said my name he said, "Hey I know you! We talked backstage." And what happened was that he'd moved over to A&R and I didn't know that. He said what I had sent was nice, but they'd heard it all before, and he asked if I could give them something unique. So I told them, that I had this other project I was working on and you might want to hear it. He said, "Well send it." So I sent him an instrumental version of "Get to Grips." He loved it, he said, "This is what I'm talkin' about!" So give me a few more like that and we can do a deal.

I had this idea for "So What" and I did it at a friend's house, and I sent it to the guy, and when he heard it, he called me right away, and he told me: "Can you get here today!" So I got on the bus and I went there, and he told me, look, "I want to sign you." And before I knew it, the legal attorney for the label was in the room, and they took my details down and it just went from there. This was early 1991, and I signed the deal in July of 1991, so it took like six months. So in August I recorded The Antidote and in November it was finished. They loved "So What" so much they said, "Look, this is going to be the single. That's the hottest thing we've heard in a long time."

What's ironic, I don't know if you've heard this, but we were think of getting Miles Davis to do the video. But we were told he wasn't feeling well.

AAJ: Didn't he die around that time?

RJ: He died the night I finished it! Do you remember the band from the 60s The Kinks?

AAJ: Oh sure.

RJ: They had a recording studio, I found it on Facebook, it's closed.

AAJ: Funny coincidence, I think Derek Trucks bought the board and some stuff from that studio.

RJ: Yeah! Well that's where we finished "So What" and Ray Davies he popped his head in the studio and said it's going to be a hit. So I met Ray, and I grew up listening to the guy, and suddenly Ray Davies is before me, and he was really commending the track. He said, "Oh I love this, it's really funky."

So anyway, I went home, I was living with my ex girlfriend. It was really late, and I put my headphones on and I played "So What" through my system and it sounded great. And just after I played it, I switched on the TV and this was 1991 and they were talking about the first Gulf War and there was a picture of Saddam Hussein and suddenly it changed to Miles Davis. And I thought, oh my God, and I knew right away what it was going to be because you don't see Miles on the news. And the newscaster announced Miles had passed away, and I was startled. So out of respect I didn't want them to release the record. And the label was like, "Are you kidding? We're going to release it!" And back then they had DAT tape, and one of the A&R guys went to a club and just played the DAT tape, and the place when crazy. This was in London, and they were like, "Who is that!"

RJ: The very first gig I did as Ronny Jordan was in December of 1991 and this was in Brixton at the Fridge, and they wouldn't let me through the door. I told them I was Ronny Jordan and they said, "Ronny Jordan is American." And I'm like, "I'm Ronny Jordan!" And then another guy came and, "It's him, it's him." So they let me in, and it was sold out, and it was an amazing show. They were freakin' out, and they started playing "So What" around the clubs. Everyone was just goin' crazy. It was the first single release on Island Records in January of 1992 and it went into the charts.

I was at Ronnie Scott's club that Sunday—Roy Ayers, the vibes player, was doing two weeks at Ronnie Scott's, and the week would run from Monday to Saturday. So Sunday was his day off, and he'd be back on Monday. So another artist will come in and perform that day, and I was there and doing the sound check. And every Sunday the new charts come out for the week, and I'd forgotten about it. So after sound check I was standing outside of Ronnie Scott's and this girl comes down the street screaming, "Twenty-nine, twenty-nine!" So they're going crazy and I'm lookin' around and asking, "What's wrong?" And they said, ""So What" just went into the charts at twenty-nine!" I was mobbed, so we did the gig that night, and the champagne was flowing and I got to meet Ronnie Scott that night. It was an amazing surreal experience and I think it was the first jazz record in the charts for 30 years—I think it was "Take Five" that was in the charts in 1962, and that was the year I was born. So now we're in 1992, and now "So What" is in the charts.

AAJ: Miles Davis must have been smiling down on that, what a great thing, it's a perfect story.

RJ: It was amazing. I was doing an interview and was asked if I'd ever heard Miles' last studio album, and I say no I hadn't heard it. And they played "The Doo Bop Song" and I almost fell of my chair, because Miles and I were in the same direction, because Miles was doing hip hop jazz too. Doo Bop was released right after The Antidote and he produced it with a New York producer named Easy Mo Bee. I never met Easy Mo Bee, but we talked on the phone and there was a possibility of him producing my second album but it didn't materialize. I wish I could have worked with him because we could have done amazing things together—but we'll never know now. But he produced Miles' Doo Bop album and it was amazing when people started comparing it to The Antidote, and people were saying if he had lived he would have approved.

People would ask me if Miles would have approved of me doing his "So What" and I said, "I think he would, because Miles was always for changing." So when Doo Bop came out in the summer of 1992, then people knew I was right, and most agreed that Miles would have approved of my doing "So What."

AAJ: Ronny I'm not a jazz historian, but when you think back, in the '20s, '30s, and '40s jazz was dance music. Are you maybe the first guy since then who brought jazz back into clubs to dance to?

RJ: It was deliberate, because I studies my history, and in order to jazz to be relevant and survive, you have to have young people involved, and you have to use modern elements. So, my thing was, if I use hip hop elements, that would attract young people. The elders, they like the beats, but they're more there for the chops. I've always described my music and music for the head and the feet.

AAJ: And I would put the heart in there too.

RJ: Absolutely, that too. I keep telling people, jazz was the pop music of its day. You had a good time. In the '60s jazz got a little cool, and then you had this free jazz movement from the late '50s, '60s, '70s and that's all well and good, but because of rock & roll and soul young people moved away from jazz. Then in the '70s it sort of came back, you had funk like Roy Ayers and George Benson.

AAJ: Didn't you get Roy Ayers in to record with you on "Brighter Day"?

RJ: Yes, we're good friends, and he's another musical influence. He may not play guitar, but he's a musical influence—I listened to a lot of his records growing up.

But in any case, it was important to keep that youth element.

AAJ: I think Wes Montgomery tried that and got a lot of grief from jazz purists about that. But he said something like, "Look, I'm playing popular music with a jazz foundation, so get over it!"

RJ: There's nothing wrong with that. There's an old saying in the South, if you ain't paying me, I'm not listening. I don't mind constructive criticism, it's healthy, but when people just criticize for the sake of criticizing, that's messed up. I don't like it. I think a lot of critics are failed musicians who never got past first base, and they are jealous of the success. They would have preferred that Wes was broke and struggling. For them, that's the beauty of jazz, when you broke and struggling, and you're trying to make ends meet. When you're successful and having hit records, that goes against the grain the the fact is, Wes crossed over, like I crossed over.

The critics seem to have a problem with it, but my thing is, they're not paying me, so I'm not listening to them. They don't have any bearing or relevance on what I do.

AAJ: You know Ronny my thing is, I talk to people whose music touches me, and that means I can be positive, enthusiastic, and honest. But if I were just churning it out and talking to people whose music I don't get or don't like, that's not a healthy combination. I think if an artist is out there giving it everything he's got, if I don't happen to like it, I'm just one person, and lots of other people may like it—so just leave it alone.

RJ: That's it, just leave it alone. I never like to criticize because you know, I don't take my opinion seriously. Everyone has an opinion, and you're totally right and I agree with you. Just because someone doesn't like something doesn't mean that it isn't good. To each his own. What I don't like, someone else will like, and as far as I'm concerned, that's legit. You know it's personal taste, and everyone has their own personal taste.

AAJ: I noticed on your last album notes you listed some of your influences, but I didn't see Charlie Christian, I wonder to you have any thought about him?

RJ: Charlie Christian was a major influence, if his name wasn't there, then that was a mistake because when you think about jazz guitar, it really started with Charlie Christian. Without him there would have been no Wes Montgomery, Grant Green, George Benson, Kenny Burrell, no Ronny Jordan, no Russell Malone. You know, Charlie Christian was "it." Sam Cooke's guitarist once described Charlie Christian as from God Almighty. When he appeared on the scene, he freaked everybody out.

AAJ: Up to that time guitar had just been part of the rhythm section and kind of in the background right?

RJ: Exactly, absolutely. There was a guy named Eddie Durham who was sort of a blues jazz guitarist. But he didn't have the chops like Charlie Christian had. He was credited as having started the electric guitar. Eddie Durham knew Charlie Christian, so once Charlie Christian got hold of it, he was the first prominent jazz guitar soloist. It was through Charlie that people got to hear jazz guitar as it is today, and he had the chops to justify that. And all of the sudden he was right up there with the horn, because prior to his ascension the horn was taking all the glory. But when he came along, he was right up there with the horn, you could hear Charlie, and his chops were out of this world. So Charlie Christian was and still is a major influence, so that was a mistake, because Charlie Christian is a major influence. It's a guitar lineage—in term of jazz guitar you have BC before-Charlie Christican and AC after-Charlie Christian.

Once the electric guitar was in his hands, people started to notice the jazz guitar, and Wes came and kind of took it to another level. But make no mistake, it started with Charlie Christian. Wes and Grant Green studied Charlie Christian and they took it to another level.

And of course George Benson came along and he went even further. My thing when coming onto the scene was not to repeat what those guys did, but to keep that spirit and use the modern vein with hip hop to bring jazz back to the street. You know, make it fun again.

AAJ: Ronny, just how popular were to albums like the The Antidote and Quiet Revolution?

RJ: Huge, just huge.

AAJ: They were like in pop territory right?

RJ: Yes, they crossed over. I didn't go overboard with the improvisation, I didn't want to alienate the listeners. Basically I wanted to spoon feed them, because a lot of them were young people. And those young people who were buying The Antidote and Quiet Revolution, it was their first introduction to jazz. Then they started getting into Miles Davis and Wes Montgomery, so yes those albums were very popular, they got into the charts.

AAJ: If someone asked me my favorite Ronny Jordan track I would have a tough time answering. Do you have a favorite?

RJ: My favorite would have to be "After Hours," and I'll tell you why. It wasn't supposed to make the album. I had the final list, and one day we were at a session and the melody was in my head and it had to come out. I had to lay it down. So said, let's just lay it down for the hell of it, and let the chips fall where they may. So we laid the beats, we laid the chords and I laid the melody. And we were looking at each other, and we were both like—wow!

So the record company guy came by, and he heard it and he was floored. We all agreed that it had to be on the album. So they asked me what the title was, and I said "After Hours" because one night I was going home and I just couldn't get it out of my head. It was late, the early morning hours, I love night time because that's when my creative juices get going.

"After Hours" broke here in America, the album The Antidote was highly influential on the Acid Jazz front, and the track "After Hours" was influential in smooth jazz, so that album did things all at one time. I was surprised, because I thought "So What" was going to be the track that would launch me in the US, but it wasn't, it was "After Hours." At that time on smooth jazz radio all you were hearing was saxophone, Kenny G, Grover Washington, Jr., Gerald Albright and guys like that, and if you were hearing any guitar it was George Benson's "Breezin," or some Larry Carlton, Lee Ritenour, you might even hear Wes Montgomergy's "Bumpin' on Sunset." You had much more sax records than guitars, but I'll tell you, once "After Hours" came out it revolutionized radio. It put the guitar right back on top.

Then you started to hear a lot of guitarists trying to sound like me. It's funny because my style is influenced by Wes Montgomery, no question, and I'm not calling any names, but you'd hear some rock guitarists who were putting their distortion pedals down, buying a Gibson L-5 and trying to sound like Wes Montgomery. (Cracking up) It was funny.

George Benson is like an uncle to me, a big brother uncle. We would go out for drinks, or go out to dinner, or hang out at the house. Once we were driving and we were listening to the radio and (laughing) George laughed and said, "Check it out, this guy is tryin' to sound like Ronny Jordan!"

AAJ: What has always impressed me with your music is that you, like Miles Davis, you are able to paint a mood with music.

RJ: Miles was always a major influence in terms of that, and the concept of "less is more." So I'm not a singer, and doing instrumental music I am trying to communicate in clear precise terms, so people can understand exactly where I'm coming from. So singing will always be the ultimate, so when Celine Dion sings, my heart will go on. Or the McCartney's' "Yesterday" or "Hey Jude" or John Lennon's "Imagine"—you understand every line.

So I'm trying to make the melody as strong as possible and memorable. Someone wrote and said he couldn't believe The Antidote is over 20 years old, because it still sounds fresh today. A fan told me the other day, "Ronny your music is timeless." I take great pride in that, and I like to think of my music as timeless.

< Previous

Rufus Reid at Mezzrow Jazz Club and D...

Comments

Tags

Talking 2 Musicians

Alan Bryson

Kenny Burrell

Grant Green

Wes Montgomery

george benson

Miles Davis

Derek Trucks

Roy Ayers

Charlie Christian

Russell Malone

Grover Washington

Gerald Albright

Larry Carlton

Lee Ritenour

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.