Home » Jazz Articles » Race and Jazz » Race, Culture and a White Boy from Texas

Race, Culture and a White Boy from Texas

"Steamwhistle power, lyric grace, alternated at will, even blended," he recalled. "Louis played mostly with his eyes closed; just before he closed them they seemed to have ceased to look outward, to have turned inward, to the world out of which the music was to flow."

Armstrong was 31 years old at the time. He had already changed the world of American music with his Hot Fives and Hot Sevens records and was spreading the gospel of jazz with a big band. A few weeks after this concert, Armstrong would record versions of "Stardust" so instrumentally stunning and vocally different from the original as to be placed in the category of the avant-garde. "Pops" was at a peak of creative power.

The young man, named Charles, was a freshman at Austin High studying Greek classics. Charles had cordial relations with black folks, and liked most he knew, especially an elder named Buck Green. Green was born and raised enslaved. When Charles was 10 years old, Green, then 75, taught him how to play harmonica. Yet, overall, whites in Austin, Texas mainly saw American Negroes in a servant's capacity. Charles later realized that black professionals and intellectuals were there too, but those sorts of "colored" folk were invisible, simply because people refused to see them.

So nothing prepared Charles for what Louis Armstrong represented: "He was the first genius I had ever seen...The moment of first being, and knowing oneself to be, in the presence of genius, is a solemn moment; it is perhaps the moment of final and indelible perception of man's utter transcendence of all else created. It is impossible to overstate the significance of a sixteen-year-old Southern boy's seeing genius, for the first time, in a black."

Charles, by the time of these reflections in 1979, had already made his mark on history, and was an old lion reflecting on his life. He recalled that back in those Depression-era days some black folk "were honored and venerated, in that paradoxical white-Southern way" but as for genius—"fine control over total power, all height and depth, forever and ever? It had simply never entered my mind, for confirming or denying in conjecture, that I would see this for the first time in a black man. You don't get over that."

That night, Charles was standing in the crowd with "a 'good old boy' from Austin High. We listened together for a long time. Then he turned to me, shook his head as if clearing it—as I'm sure he was—of an unacceptable though vague thought, and pronounced the judgment of the time and place: 'After all, he's nothing but a God damn nigger!'

"The good old boy did not await, perhaps fearing [a] reply. He walked one way and I the other. Through many years now, I have felt that it was just then that I started walking toward the Brown case, where I belonged. I realized what it was that was being denied and rejected in the utterance I have quoted, and I realized, repeatedly and with growingly solid conviction through the next few years, that the rejection was inevitable, if the premises of my childhood world were to be seen as right, and that, for me, this must mean that those premises were wrong, because I could not and would not make the rejection. Every person of decency in the South of those days must have had some doubts about racism, and I had mine even then—perhaps more that most others. But Louis opened my eyes wide, and put to me a choice. Blacks, the saying went, were 'all right in their place.' What was the 'place' of such a man, and of the people from which he sprang?"

Charles didn't deny the blinding, Saul-on-the-road-to-Damascus-become-Paul experience that transformed him that night. He accepted what he heard and felt and what he knew he saw. When brought face-to-face with an "other" who, in society, represents all equated with "inferior," yet that other is the total opposite of society's judgment—is not only "superior" but genius—you have a choice to make. Charles had to make a moral choice whether to go against the social norms about "race" in his Southern white upbringing. He eventually became, according to that upbringing, a traitor to his race and his class, what the redneck "good old boys" would later call an unrepentant "nigger-lover."

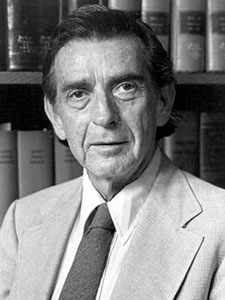

Charles L. Black, Jr. became a constitutional law professor who, for a half century, helped shape the legal minds of students at Columbia and Yale law schools (current U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton studied with Black, and consulted him when she was working on the House Judiciary Committee in 1974 on the Nixon impeachment inquiry). Charles L. Black, Jr., as remembered in his New York Times obituary on May 8, 2001, helped "Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Inc., and others, to write the legal brief for Linda Brown, a 10-year-old student in Topeka, Kan., whose historic case, Brown v. Board of Education, became the Supreme Court's definitive judgment on segregation in American education." Charles L. Black, Jr. is a sterling example of moral courage, and his story above, which comes from an essay in the Yale Review titled "My World with Louis Armstrong," demonstrates, too, the power of culture over race.

Charles L. Black, Jr. became a constitutional law professor who, for a half century, helped shape the legal minds of students at Columbia and Yale law schools (current U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton studied with Black, and consulted him when she was working on the House Judiciary Committee in 1974 on the Nixon impeachment inquiry). Charles L. Black, Jr., as remembered in his New York Times obituary on May 8, 2001, helped "Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Inc., and others, to write the legal brief for Linda Brown, a 10-year-old student in Topeka, Kan., whose historic case, Brown v. Board of Education, became the Supreme Court's definitive judgment on segregation in American education." Charles L. Black, Jr. is a sterling example of moral courage, and his story above, which comes from an essay in the Yale Review titled "My World with Louis Armstrong," demonstrates, too, the power of culture over race. I assert that one of the ways we can begin move beyond the scourge of race and racism is to view human dynamics and interaction (including, of course, jazz) in terms of culture rather than race, as a start. Let's briefly look at the two ideas aside from jazz, and then bring back in the music.

Race is a slippery, shape-shifting idea that in its modern guise has only been around for a few hundred years. Before modernity, race was used to classify groups of people, but it wasn't as tied to physical and phenotypic characteristics as it has become in more recent times. Before the modern period—in the West, approximately the time from the European Enlightenment to the late-1950s—language, custom, religion, status and class were more important than physical appearance in determining categorization of groups based on difference.

And while it's important to acknowledge that scientific research has shown that a suspicious or negative view of "others" different from oneself or one's group seems to be a universal cognitive response among humans, it's also crucial to say that the race meme is what post-modernists call a "social construction." It's a social invention used to categorize others and justify social and economic domination; scientific research has also revealed that a folk conception of race is not based on genes or biological essences. Early scientific research in the 18th, 19th, through the middle 20th century not only equated race with biology, but also used scientific rationale to explain why certain groups were "inferior" to others, which gave justification for chattel slavery, Jim Crow and other forms of social and material domination inscribed into law as well as what author Albert Murray calls the folklore of white supremacy.

So if, as Herbert Spencer argued in the 19th century, human races evolved based on the "survival of the fittest," that logic demonstrated why those at the bottom of the social totem pole are there. His adaptation of Darwin's theory of evolution to the social realm was an example of a conflation of distinct categories—individual, cultural and social—that plagues us to this very day.

The European Enlightenment led to the ideas of liberty and natural rights as universal human values—in theory. Abstract ideals such as democracy, freedom and equality were all foundational principles to the founding of the American nation, yet ironically those salutary values were equated with whiteness and measured by the extent to which blacks (and others not considered "white") were not free and equal.

In the Winter 2011 issue of Daedalus, the quarterly journal of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Amherst College Professor of American Studies Jeffrey B. Ferguson has an essay titled, "Freedom, Equality, Race." In it he says: "Many writers have observed that the Enlightenment, through its emphasis on human powers, gave freedom its modern meaning; but it also codified the modern idea of race as one way to distinguish those worthy of liberty from the irrational, uncivilized, and superstitious 'others' who supposedly lived in a perpetual past. In other words, this period handed down most of the reasons to believe in race along with the justification for despising and resisting it...From their inception, the concepts of freedom and race have reinforced each other in the making of modernity; they continue to do so today, though the concept of race has shifted in its definitional grounding, from nature to culture...the post-civil rights concept of race relies on values, modes of signifying, and behavior."

Today, racism, in both individual and structural dimensions, functions like an ideological shadow, and is rarely stated explicitly in the bald, gross terms of the pre-Civil Rights era. For instance, the man Bill Cosby calls Donald Tramp played his trump card by calling for the release of the long-form birth certificate of a sitting President of the U.S.A., who had been fully vetted during the 2008 campaign by the governmental apparatus, in order to question his authenticity as an American citizen. And even after the President shows the birth certificate, Mr. Chump says that President Obama should stop playing basketball to attend to the economy, and that there's no way that he wrote his best-selling memoir, and that he didn't have the grades to get into Columbia and Harvard. He says the latter about a man who graduated magna cum laude from Harvard Law School, after serving as president of the prestigious Harvard Law Review. And, oh, don't forget: Trump has a good relationship with "the blacks."

Today, racism, in both individual and structural dimensions, functions like an ideological shadow, and is rarely stated explicitly in the bald, gross terms of the pre-Civil Rights era. For instance, the man Bill Cosby calls Donald Tramp played his trump card by calling for the release of the long-form birth certificate of a sitting President of the U.S.A., who had been fully vetted during the 2008 campaign by the governmental apparatus, in order to question his authenticity as an American citizen. And even after the President shows the birth certificate, Mr. Chump says that President Obama should stop playing basketball to attend to the economy, and that there's no way that he wrote his best-selling memoir, and that he didn't have the grades to get into Columbia and Harvard. He says the latter about a man who graduated magna cum laude from Harvard Law School, after serving as president of the prestigious Harvard Law Review. And, oh, don't forget: Trump has a good relationship with "the blacks." But don't feel sorry for President Obama; he's no victim. His personality and character is grounded in conscious, articulate culture, which he's studied, adapted and models. On Saturday evening, April 30th, the President roasted the Donald in his face, slicing and dicing him with cool precision at the White House Correspondent's Dinner. The next night President Obama announced to the world that Osama Bin Laden had been killed. The coup de grace was the President appearing on Oprah the very next day with the gorgeous First Lady to his right, Oprah to his left, and an adoring audience straight-ahead. Sorry Donald, but you can't touch this.

If you were wondering what "mode of signifying" meant in the last sentence of the quote three paragraphs above, now you know. Imagine a big sign with the word "race" written on it, and then realize that Trump and the Birthers were signifying on that sign, giving meaning to that sign, thereby enacting a subtler form of racism. This is an example of the way race has shifted from nature (biology) to culture, by use of rhetorical codes that serve as winks to insiders who share common reference points, usually based on stereotypes. So in the case of President Obama, the implication is that he's an inauthentic phony. Why? Because articulate and accomplished black men who aren't athletes or entertainers are suspect, too bourgeois, not real enough, not really street, ghetto, and are likely affecting airs. Why? Because the image of a successful black man in non-entertainment/athletic fields too strongly counters the stereotypes that support the notion of black inferiority. In person, on a dark street in an urban area, after hours, many people would feel more comfortable seeing someone like Obama walking down the street clean in a business suit as compared to, say, the thuggish image of a 50 Cent and his crew with their jeans hanging off their backsides. But the image of 50 Cent is less threatening to the myth of white supremacy than is a Barack Obama, or a Richard Parsons or Ken Chenault or even Ursula Burns —who as CEO of Xerox, counters stereotypes of race and gender—in the corporate sphere.

So tear down Obama's legitimacy by implying that he's more concerned with basketball—highly associated with black men—than with the economy, by implying that he could have only been accepted to Ivy League institutions because of affirmative action (over and above more deserving white applicants, of course, victims of "reverse racism"), not because he earned good grades and SAT and LSAT scores, and by implying that he's a spook who must've employed a ghost writer to pen his memoir, Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance, because, you know, they can't really master the English language that well. The racial subtext of Trump's statements were so clear that he was criticized roundly in print and broadcast media.

Racialist chumps use tropes based in stereotypes to signify on those race signs that political correctness and social politeness and fear have excised from the public discourse, but that remain in minds and belief systems nevertheless. To continue to comprehend how race has spread its weed-like branches to the cultural realm, let's look at "culture" as an idea proper, and then modulate back to jazz.

For many of us, the first time we recall hearing about culture was when we cultivated bacterial cells in Petri dishes in biology class. So, by extension, culture is a kind of environment. Another analogy would be that water serves as the culture fish live in. It's a natural environment to the fish, whereas our culture is the natural inner environment of collective feelings, values, myths, and the sympathetic resonance we have in common with others we identify with. Soon we'll see that culture is also meanings and tools and artifacts.

The late anthropologist Clifford Geertz once defined culture as "an ensemble of stories we tell about ourselves." The economy of that definition is elegant; relating a fundamental human practice such as story-telling with "ensemble," a word wonderfully allusive to music, appeals to an aesthetic sensibility. Yet let's continue with other definitions so our description of culture can become thick and textured.

American philosopher Ken Wilber places culture in the Lower Left of his Integral four-quadrant map of human reality. (Click image on the right to enlarge.) In his work A Brief History of Everything, Wilber writes that cultural "refers to all of the interior meanings and values and identities that we share with those of similar communities, whether it is a tribal community or a national community or a world community. And 'social' [Lower Right quadrant] refers to all of the exterior, material, institutional forms of the community, from its techno-economic base to its architectural styles to its written codes to its population size, to name a few."

American philosopher Ken Wilber places culture in the Lower Left of his Integral four-quadrant map of human reality. (Click image on the right to enlarge.) In his work A Brief History of Everything, Wilber writes that cultural "refers to all of the interior meanings and values and identities that we share with those of similar communities, whether it is a tribal community or a national community or a world community. And 'social' [Lower Right quadrant] refers to all of the exterior, material, institutional forms of the community, from its techno-economic base to its architectural styles to its written codes to its population size, to name a few." The insights of post-modernism fit neatly within the cultural quadrant also, according to Wilber. In Appendix I of Integral Spirituality (p. 224) he says that "Postmodernism...is known for focusing on those interior or cultural aspects of an individual's being-in-the-world, where it emphasizes that much of what any society takes to be 'given,' 'true,' and 'absolute' is in fact culturally molded, conditioned, and often relative."

Albert Murray, author of Stomping the Blues, The Hero and the Blues, South to a Very Old Place, among other works, is one of the most significant writers on blues and jazz of the late-20th century. In his first book, The Omni-Americans (1970), Albert Murray asserts: "White Anglo-Saxon Protestants do in fact dominate the power mechanisms of the United States. Nevertheless, no American whose involvement with the question of identity goes beyond the sterile category of race can afford to overlook another fact that is no less essential to his fundamental sense of nationality no matter how much white folklore is concocted to obscure it: Identity is best defined in terms of culture ...American culture, even in its most rigidly segregated precincts, is patently and irrevocably composite. It is, regardless of all the hysterical protestations of those who would have it otherwise, incontestably mulatto. Indeed, for all their traditional antagonisms and obvious differences, the so-called black and so-called white people of the United States resemble nobody else in the world so much as they resemble each other. And what is more, even their most extreme and violent polarities represent nothing so much as the natural history of pluralism in an open society."

Albert Murray, author of Stomping the Blues, The Hero and the Blues, South to a Very Old Place, among other works, is one of the most significant writers on blues and jazz of the late-20th century. In his first book, The Omni-Americans (1970), Albert Murray asserts: "White Anglo-Saxon Protestants do in fact dominate the power mechanisms of the United States. Nevertheless, no American whose involvement with the question of identity goes beyond the sterile category of race can afford to overlook another fact that is no less essential to his fundamental sense of nationality no matter how much white folklore is concocted to obscure it: Identity is best defined in terms of culture ...American culture, even in its most rigidly segregated precincts, is patently and irrevocably composite. It is, regardless of all the hysterical protestations of those who would have it otherwise, incontestably mulatto. Indeed, for all their traditional antagonisms and obvious differences, the so-called black and so-called white people of the United States resemble nobody else in the world so much as they resemble each other. And what is more, even their most extreme and violent polarities represent nothing so much as the natural history of pluralism in an open society." In 1994, novelist Louis Edwards interviewed Murray in his Harlem apartment, where he lived with his wife Mozelle and daughter Michelle. Murray clarified both the term Omni-American and the race vs. culture debate in this exchange:

Albert Murray: 'Omni-Americans' means 'all-Americans.' America is interwoven with all these different strains. The subtitle of that section of the book is 'E Pluribus Unum'—one out of many...It just means that people...represent what Constance Rourke calls a composite. Then you can start defining individuals in their variations, but they're in that context and they can only define themselves in that context. They're in a position where they're the heirs of all the culture of all the ages. Because of innovations in communications and transportation, the ideas of people all over the world and people of different epochs impinge upon us, on part of our consciousness.

Louis Edwards: Then the term 'omni-Americans' applies not just to African-Americans, but to all Americans, and to—well, maybe not to all people, but perhaps we're discussing 'omni-humanity.'

AM: Yes. Absolutely. We're looking for universality. We're looking for the common ground of man. And what you're doing when you separate the American from all of that, is you're talking about idiomatic identity. You see? And if you go from culture, instead of the impossibility of race...It doesn't meet our intellectual standard with a scientific observation and definition. You see, race is an ideological concept. It has to do with manipulating people, and with power, and with controlling people in a certain way. It has no basis in reality...So what you enter into to make sense of things are patterns and variations in culture. What you find are variations we can call idiomatic—idiomatic variations. People do the same things, have the same basic human impulses, but they come out differently. The language changes because of the environment and so forth. Now, you can get the environment, you can get the cultural elements, and from those things you can predict the behavior of people fairly well. But if you look at such racial characteristics as may be used—whether it's the shape of certain body parts, the texture of the hair, the lips, and all—you cannot get a scientific correlation between how the guy looks and how he behaves. If you find a large number of people who look like each other and behave like each other, it's because of the culture... If you've got guys from stovepipe black to snow blond, you're going to find all the variations in mankind, even though idiomatically they might speak the same, they might sound the same.

Murray and Ralph Ellison—Murray's friend and fellow student at the Tuskegee Institute in the 1930s and author of the classic 1952 novel, Invisible Man—form an intellectual foundation and bulwark that I call the Ellison-Murray Continuum. In-depth study of their writings will reveal a continuity of themes and preoccupations, yet with different styles and modalities of expression. The two were in full agreement about the import of blues and jazz as exemplars of black American culture writ small as well as American culture, values and meaning writ large. As you'll see, they also shook hands in their view of race and culture.

In 1963, Ellison wrote a definition of "cultural complex": "I'm talking about how people deal with their environment, about what they make of what is abiding in it, about what helps them to find their way, and about that which helps them to be at home in the world. All this seems to me to constitute culture." From the kinship and comfort of "home," the internal compass implied by "what helps them to find their way" to the normative values of "what is abiding in it" as well as the personal and interpersonal response to social reality ("their environment"), Ellison crafted an interpretation of culture clear in common sense tonalities while maintaining fidelity to the term's anthropological origins.

In 1963, Ellison wrote a definition of "cultural complex": "I'm talking about how people deal with their environment, about what they make of what is abiding in it, about what helps them to find their way, and about that which helps them to be at home in the world. All this seems to me to constitute culture." From the kinship and comfort of "home," the internal compass implied by "what helps them to find their way" to the normative values of "what is abiding in it" as well as the personal and interpersonal response to social reality ("their environment"), Ellison crafted an interpretation of culture clear in common sense tonalities while maintaining fidelity to the term's anthropological origins. Here's Ellison on the origins of a hybrid national American identity: "Out of democratic principles set down on paper in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights they were improvising themselves into a nation, scraping together a conscious culture out of the various dialects, idioms, lingos, and mythologies of America's diverse peoples and regions." Conscious culture is an important idea because usually we think of culture as so inherited by our environment as to be underneath our waking awareness of it, like fish in the sea. Yet by way of thorough education and commitment to specific principles and values, you can consciously create and/or influence a culture.

Once you're hip to how culture works, you can articulate and re-enact the force of culture for the good, the beautiful and the true. This is one of the highest purposes and functions of art and artists. You can use culture, in her personal and interpersonal extensions, to bring about changes in the social realm that can be seen and measured. But you have to play, to swing, to swim in the realms of the invisible, but no less real, dimensions. Inner, interior dynamics, from feelings and memories to cultural tools and meanings, can be marshaled in this way. That's what writers do; that's what artists do. Music itself is called the art of the invisible, so turn inward, to the world out of which music flows. The narrative arc here points to the always resonant metaphor of the hero. So, one way to use culture, in this heroic model, this hero metaphor, this variation on Heru (Horus) of ancient Kamit (Egypt), is to combine your personal energy, integrity, talent, intellect, and power with others who share the same vision, mission, and willingness to act courageously in the world.

Ellison also thought that culture is about exchange and interchange, a dialectical and dialogical process in which cultural forms and ideas are utilized freely in an open, pluralistic society. "You are not going to lose a certain way with words because it is built into the way we speak," he said in 1973 to journalist Hollie I. West. "What we call rapping or riffing—you are going to hear your daddy talking or your uncle or your older brothers and sisters. This is preserved in speech and its informed attitudes, which can range from the most explicit to that which is implicit and subtle...What will happen, I think, is that as you become conscious as an artist, you will begin to exploit it consciously. You will work at it in terms of what others have done in other cultures. You will abstract motives from there and impose them within your own scheme.

"But it's a give-and-take human thing rather than a racial thing, and at some point we're going to have to realize that simply by having the same skin we're not all the same people. There are many cultural levels within the Negro group. There are people who are on the folk level in their cultural lives, even though they might be operating computers. And there are people who shine shoes who, in their cultural lives, are on the high level of articulate culture.

Hollie I West: This reminds me of something that Duke Ellington said to me in an interview. He said the pull of American culture was so strong that no one could resist it.

Ralph Ellison: Not only that, but it's in the artifacts, you see...Negroes thought they were going to isolate themselves by putting on an Afro. The Jewish kids, the blonde kids—they're wearing them too. Why? Because it's irresistible. It's a style. It's a new way of making the human body do something; and it operates over and beyond any question of race."

In 1967, three black male writers interviewed Ellison in his Harlem apartment on Riverside Drive for Harper's magazine. The result, "A Very Stern Discipline," is a classic ritual encounter of journeymen with an elder master, who instructs through representative anecdotes, spanning the globe with literary, political and historical insight, relating to the young men—Steve Cannon, Lennox Raphael, and James Thompson—their ancestral imperative within a particular Afro-American moment as it extended to the larger fractal American vibration within a global context. This revealing passage functions as a variation on the themes of this essay:

In 1967, three black male writers interviewed Ellison in his Harlem apartment on Riverside Drive for Harper's magazine. The result, "A Very Stern Discipline," is a classic ritual encounter of journeymen with an elder master, who instructs through representative anecdotes, spanning the globe with literary, political and historical insight, relating to the young men—Steve Cannon, Lennox Raphael, and James Thompson—their ancestral imperative within a particular Afro-American moment as it extended to the larger fractal American vibration within a global context. This revealing passage functions as a variation on the themes of this essay: "Recently we had a woman from the South who helped my wife with the house but who goofed off so frequently that she was fired. We liked her and really wanted her to stay, but she simply wouldn't do her work. My friend Albert Murray told me I shouldn't be puzzled over the outcome. 'You know how we can be sometimes,' Al said. 'She saw the books and the furniture and paintings, so she knew you were some kind of white man. You couldn't possibly be a Negro. And so she figured she could get away with a little boondoggling on general principles, because she'd probably been getting away with a lot of stuff with Northern whites. But what she didn't stop to notice was that you're a Southern white man...'"

By the way, this was a time when the word Negro, signifying U.S.-born and bred blacks, hadn't been dropped by Ellison's generation. They knew of the long struggle to capitalize the "N" and agreed with what the word signified as regards ethnicity, culture and nationality.

"So you see, here culture and race and a preconception of how Negroes are supposed to live—a question of taste—had come together and caused a comic confusion. Such jokes as Al Murray's are meaningful because in America culture is always cutting across racial characteristics and social designations. Therefore, if a Negro doesn't exhibit certain attitudes, or if he reveals a familiarity with aspects of the culture, or possesses qualities of personal taste which the observer has failed to note among Negroes, then such confusions in perception are apt to occur.

But the basic cause is, I think, that we are all members of a highly pluralistic society. We possess two cultures—both American—and many aspects of the broader American culture are available to Negroes who possess the curiosity and taste—if not the money—to cultivate them. It is often overlooked, especially in our current state of accelerated mobility, that it is becoming increasingly necessary for Negroes themselves to learn who they are as Negroes. Cultural influences have always outflanked racial discrimination—wherever and whenever there were Negroes receptive to them, even in slavery times. I read books which were free to me for my work as a writer while studying at Tuskegee Institute, Macon County, Alabama, during a time when most of the books weren't even taught. Back in 1937 I knew a Negro who swept the floors at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, who was nevertheless designing planes and entering designs in contests. He was working as a porter but his mind, his ambitions, and his attitudes were those of an engineer. He wasn't waiting for society to change, he was changing it by himself."

Cultural influences have always outflanked racial discrimination

there are people who shine shoes who, in their cultural lives, are on the high level of articulate culture

it's in the artifacts, you see

it's a give-and-take human thing rather than a racial thing

culture is about exchange and interchange, a dialectical and dialogical process in which cultural forms and ideas are utilized freely in an open, pluralistic society

how people deal with their environment, about what they make of what is abiding in it, about what helps them to find their way, and about that which helps them to be at home in the world

What you enter into to make sense of things are patterns and variations in culture...idiomatic variations

They're the heirs of all the culture of all the ages...the ideas of people all over the world and people of different epochs impinge upon us, on part of our consciousness

the so-called black and so-called white people of the United States resemble nobody else in the world so much as they resemble each other

the interior meanings and values and identities that we share with those of similar communities, whether it is a tribal community or a national community or a world community

an ensemble of stories we tell about ourselves

the inner environment of collective feelings, values, myths, and the sympathetic resonance we have in common with others we identify with

Culture was the foundation of Charles L. Black Jr.'s reaction to Louis Armstrong, not race. The fact that Armstrong was black, in racial terms, was a part of the meaning that Black attributed to the cognitive dissonance he experienced by seeing and feeling genius through the sound and performance of a black man, yes. But meaning is a cultural dynamic; and as such it surely can trip us up or free us based on how we as individuals and groups of people choose to respond to those meanings. Charles L. Black Jr. was freed from the constraints of "the judgment of the time and place" of the community in Texas in which he grew up by choosing to transcend them, which later helped the country move beyond the overt legal segregation in education via the Brown vs. Board of Education case.

Culture was the foundation of Charles L. Black Jr.'s reaction to Louis Armstrong, not race. The fact that Armstrong was black, in racial terms, was a part of the meaning that Black attributed to the cognitive dissonance he experienced by seeing and feeling genius through the sound and performance of a black man, yes. But meaning is a cultural dynamic; and as such it surely can trip us up or free us based on how we as individuals and groups of people choose to respond to those meanings. Charles L. Black Jr. was freed from the constraints of "the judgment of the time and place" of the community in Texas in which he grew up by choosing to transcend them, which later helped the country move beyond the overt legal segregation in education via the Brown vs. Board of Education case. He wasn't waiting for society to change, he was changing it by himself

Yet culture is also tools, according to the late-anthropologist Paul Bohannan in How Culture Works (1995). Bohannan details how culture "emerges from life just as life emerges from matter" and defines culture as a combination of the tools and the meanings that expand behavior, extend learning, and channel choice. Black exercised choice after he learned that the social norms were incomplete and inadequate, and his behavior expanded to incorporate his fellow Southern kin who happened to have darker skin.

The cultural tool that enabled this transcendence to occur was the music—a social and cultural artifact—the jazz, the might and right manner in which Armstrong took a cold metal instrument and blew threw it the warm majesty of his soul and his awe-inspiring talent. Jazz, as a cultural tool to reach bodies, hearts and minds and souls and spirits, also incorporates the affirmative values of fluid freedom within disciplined form, acceptance of the blues of life while perpetually swingin' to confront them, individual expression and style within an pluralistic, democratic ensemble context, integral improvisation as self-invention, technical mastery in service of emotional depth, and what writer Stanley Crouch calls the "sound of spiritual investigation in a secular frame."

Furthermore, in the same manner that jazz musicians play with and against form to achieve a personal voice within and against a past tradition, Charles Black, a product of the white South, created a personal voice and moral integrity that was within and against his upbringing. This pattern is also found in literature, according to Ellison: ..."literature teaches us than mankind has always defined itself against the negatives thrown it by both society and the universe. It is human will, human hope, and human effort which make the difference. Let's not forget that the great tragedies not only treat of negative matters, of violence, brutalities, defeats, but they treat them within a context of man's will to act, to challenge reality and to snatch triumph from the teeth of destruction."

Perhaps Charles L. Black Jr. intuitively felt all of this through the profound human artistry of Louis Armstrong.

"There have been many—well, a good many—great artists in my time," wrote Black. "But it happened that the one who said the most to me—the most of gaiety, the most of sadness, the most of nervous excitement, the most of religion-in-art, the most of home, the most of that strange square-root-of-minus-one world of emotions without name—was and is Louis. The artist who has played this part in my life was black."

His reflections continue, encompassing the people from which Armstrong sprang and the culture he and they shared: "In 1957, in the early days after the Brown case, when the South was still resisting, I wrote out and published my deepest thought on the nature of the agony as it presented itself:

I'm going to close by telling of a dream that has formed itself through the years as I, a Southern white by birth and training, have pondered my relations with the many Negroes of Southern origin that I have known, both in the North and at home.

I have noted again and again how often we laugh at the same things, how often we pronounce the same words the same way to the amusement of our hearers, judge character in the same frame of reference, mist up at the same kinds of music. I have exchanged 'good evening' with a Negro stranger on a New Haven street, and then realized (from the way he said the words) that he and I derived this universal small-town custom from the same culture...

These and thousands of other such things have brought me to see the whole caste system of the South, the whole complex net of its senseless cruelties and cripplings, as no mere accidental grotesquerie of history, but rather as that most hideous of errors, that prima materia of tragedy, the failure to recognize kinship...My dream is simply that sight will one day clear and that each of the participants will recognize each other.

The question to you, dear reader, is whether or not you will recognize your own culture—a real category of human reality rather than the social construction of race—and then articulate—freely—your own conscious culture, based on human commonality, and in celebration of human variety and difference? If so, then we can shake hands with Ellison's nameless character at the end of Invisible Man, when he says: Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?

Part 3: Gary Giddins on Ignored Black Jazz Writers

Photo Credit

Page 7: T. Charles Erickson

< Previous

School Days

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.