Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Nat Birchall: Alone In The Music

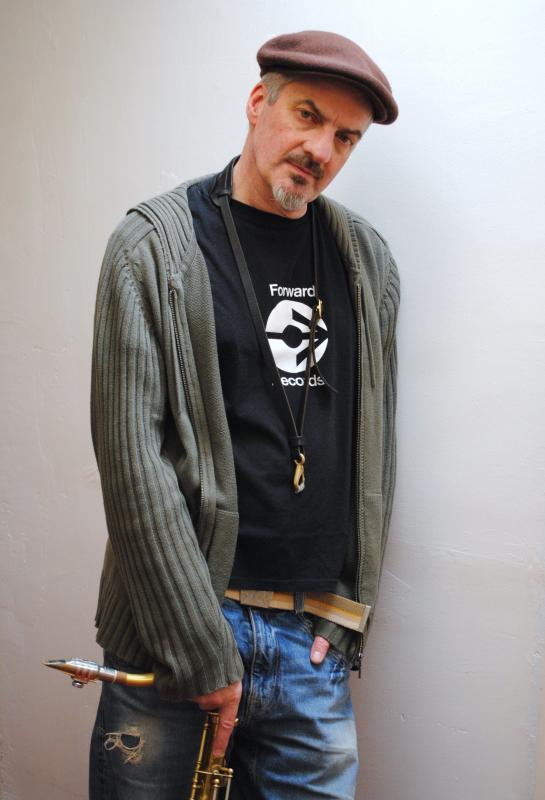

Nat Birchall: Alone In The Music

Two of the most over-used phrases in music journalism are "overnight star" and "out of nowhere," and so apologies for starting with them here. But when it comes to describing British saxophonist Nat Birchall, they have an unusual degree of exactitude. Birchall, born in 1957 in the rural seclusion of the hill country of North-West England, where he still lives in 2010, and a saxophonist since 1979, didn't make an impression on Britain's national jazz scene until 2009, when he released his second album, Akhenaten, on fellow Lancastrian, trumpeter Matthew Halsall's Gondwana label.

Two of the most over-used phrases in music journalism are "overnight star" and "out of nowhere," and so apologies for starting with them here. But when it comes to describing British saxophonist Nat Birchall, they have an unusual degree of exactitude. Birchall, born in 1957 in the rural seclusion of the hill country of North-West England, where he still lives in 2010, and a saxophonist since 1979, didn't make an impression on Britain's national jazz scene until 2009, when he released his second album, Akhenaten, on fellow Lancastrian, trumpeter Matthew Halsall's Gondwana label. The media embrace was immediate, and—practically overnight—Birchall and his John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders-inspired "spiritual" jazz became hot topics of conversation. 2010's follow-up album, Guiding Spirit, also on Gondwana, has raised the temperature further. Without warning, Birchall has become a name to reckon with.

Using, basically, Halsall's uniquely empathetic band—Halsall, pianist Adam Fairhall, bassist Gavin Barras and drummer Gaz Hughes—Birchall has made two of the most exquisitely soulful and lyrical albums of the new century. They reflect his love of both the Coltrane/Sanders astral jazz oeuvre, and also of the "conscious" reggae which was his original route into music. The reggae connection isn't explicit on the discs, but the spiritual reasoning which is part of its legacy is key to Birchall's outlook on life, as can be inferred from the titles he gives some of his compositions.

Birchall began playing with bands in the mid-1980s, in jazz-funk, jazz-rock and Turkish jazz-fusion outfits. In 1992, he formed his own Corner Crew group, playing a jazz-influenced hip-hop style featuring a rapper and sampling. It was, Birchall recalls, a fine band, but "it often felt like I was simply complementing the groove that was determined by the rhythm section." In 1998, he formed Sixth Sense, who released the hard bop-rooted Sixth Sense on its own, eponymous label in 1999.

A new band followed in the early noughties, but still Birchall—far away from the bigger pool of musicians centered around London—was struggling to find like-minded colleagues. "Experience has taught me that you can't get anyone to play a certain way if they don't want to, or can't feel it," says Birchall. "When it comes down to it, they are going to play what is in their hearts. So you have to wait until you find the right people to play with you in the way you'd like."

So Birchall continued, "playing in a bubble," as he puts it, "alone in the music," until meeting Matthew Halsall in early 2007. And the outpouring of love and spirituality on Akhenaten and Guiding Spirit sounds all the sweeter for the long years in the wilderness that preceded them.

All About Jazz: Let's start at the beginning. What was the first music you can remember hearing?

All About Jazz: Let's start at the beginning. What was the first music you can remember hearing? Nat Birchall: The first I can recall was on the radio my parents had in the kitchen. Someone singing "English Country Garden." Many years later, I heard [saxophonist] Charlie Parker quote it at the end of one of his live performances. It seemed for a moment as though he was acknowledging my earliest musical memories from beyond the grave.

I didn't study music at school, but I started buying records in late 1971. Isaac Hayes' "Theme From Shaft" was the first one. Back then, most people my age in the area were either into progressive rock or soul, but something about reggae spoke to me in a way that soul or rock music didn't. I started to buy all the reggae records I could find. In the mid 1970s, I would go to Liverpool, to a specialist reggae shop in the Toxteth area, to buy tunes.

AAJ: So reggae was your first love?

NB: Oh yes—and it's still a big love. But in the mid 1970s I was into roots and dub to the exclusion of anything else. I would spend all my money on these records, and the people in the village would be like, "What the hell is that? You're weird!" Coming from the northern countryside I didn't meet too many black people until I was in my late teens, so I was a man alone in the music I was listening to. And I think maybe I've always had this thing that my music is not what the majority of people are into. I loved the music deeply, but I never thought of myself as someone who could actually be a musician.

It was reggae that got me playing saxophone. In 1979, I lent some albums to two friends who were going to take up saxophone and flute. I dug out all my records with sax and flute on them. They were mostly reggae—I had one jazz album, Coltrane's Blue Train [Blue Note, 1957]. Somehow, in the process of digging these discs out, I got a yen to learn myself, and shortly afterwards I noticed an old alto in the back of a record shop, that the guy was going to use in a window display. I persuaded him to sell it to me for £20.

After playing it for five minutes, I knew I had to take it seriously. I really connected with it. I could hear the sound in the instrument that I'd been hearing on all the Jamaican records I'd been buying. So I saved up some money, borrowed a bit more, and bought a decent vintage alto. A year later I traded it for a tenor. I also started to listen to jazz. I knew that all the Jamaican horn players I loved—Cedric Im Brooks, Tommy McCook, Roland 'Ringo' Alphonso—were jazz players and their music was influenced by Coltrane. And I started to buy jazz records.

AAJ: Did you take any lessons?

NB: I started to take lessons as soon as I got my first decent saxophone, with a local player, Harold Salisbury. He was getting on towards middle age, and most guys of that age in Lancashire, back then anyway, were into big band swing stuff. But Harold was really into "modern" jazz. I already knew about Coltrane and Sonny Rollins, but he turned me on to other saxophonists, like Billy Harper and George Adams. I would leave each lesson with a pile of LPs, tape them all and go back 2 weeks later for another lesson and more LPs.

I think I maybe had 10 or 12 lessons or so before I stopped going. Harold was a very enigmatic teacher—so enigmatic that he'd almost never tell me anything specific, insisting that I could/should work it out myself. I see the value in it now, but back then I felt that I really needed something concrete to practise, so I kind of drifted away from the lessons.

I didn't have another formal music lesson until 1994, when I did an HND [Higher National Diploma] in jazz studies. I'd always played by ear. I thought all non- classical musicians did. But you can only go so far in jazz that way, unless you're gifted, which I'm not. So I really had to buckle down and learn the theory.

Immersing myself in all that harmonic theory had a very negative effect on my playing; all of a sudden I couldn't play without thinking anymore. I couldn't play without thinking of the chord and what I "should" play. It took me a while to work through it and get to where I could switch off, or perhaps switch on. That took me two or three years to work through, until I could function in a way that was acceptable to me.

AAJ: You talked earlier about being "alone in the music," when you first started listening to reggae. Has that feeling continued through your journey in jazz?

NB: I've always had the impression that, while most other musicians acknowledge the whole Coltrane-axis thing, they don't see it the same way that I do. For me, there's nothing as deep, as all-encompassing as Coltrane's music—both in terms of the actual music and also of what that music suggests in an abstract or "spiritual" sense. I never could understand why anyone wouldn't want to pursue that kind of playing. It is just so powerful to me. And that spirituality, for want of a better word, has gradually become the main focus of my playing.

So within the musical world in which I've operated I've often felt like an outsider, having a different agenda than everyone else. There's also the question of the audience. There's not a huge amount of people who actually want to listen to this music, not in North-West England at any rate, so I've often had the feeling that I'm tilting at windmills.

AAJ: But that changed, presumably, when you met Matthew Halsall?

NB: The first time I played with his band, round about spring 2007, it was almost like, this is the band I've been waiting to join in all the 30 years I've been playing! It was so conducive to my style of playing that I felt right at home. Matt's a man who I have a lot of time for, I love his playing, his music, his concept. He's so organized in ways that I'm really not. I've never met anyone who's got their music and the business side down like he has. He's really opened the way for me to find myself as a musician, after all this time.

When we did the first session for what was to become my Akhenaten album [Gondwana, 2009], we did the first tune and something happened—I mean I literally felt very different whilst playing the first tune, "Nica's Dance," and could feel something special in the music, that I hadn't felt before. In retrospect I believe it was because of the other musicians and how they played. They were all incredibly supportive and selfless and played with real soul. I also think that, for whatever reason, my compositions now express my true self in a way that my previous attempts at writing hadn't.

It felt like I was playing me somehow, in a way that I hadn't before. My music is very simple, harmonically and melodically, so you really have to play with as much conviction as possible because there's nothing to hide behind if you know what I mean. Since that day I've played differently, or at least I feel so, and I try to write songs that emote the way I feel about music, life, the universe. It's only since playing with Matt's band and writing these songs that I've really found myself as a musician.

When I write tunes, I have to kind of "find" them, on the piano or on the horn. There's a school of thought that says that all tunes already exist and we just discover them, which is kind of how I see it too. I don't think I could sit down and say, "Today I'm going to write a song in a [hard bop pianist] Horace Silver style" or whatever. That would probably result in a very cliched tune. So the songs have their own concept; they aren't designed to fit with any plan for a particular album or project.

With the 2010 album, Guiding Spirit, I was conscious that I didn't want to do "Akhenaten Part II." It had to be different enough to be distinct from it, but at the same time be a natural progression. So there was an effort to try to find more upbeat type tunes and for us to play with a stronger dynamic than on the last one. I wanted to use percussion because I hear it working with the way the music is going. In the future, I think I'd like the percussion to be more integral within the foundation of the music; it sounds a bit complementary to me on the album.

The core of the band are some of the most empathic people I've ever played with. They are absolutely integral to the outcome of the music. They play completely in the moment, in a very selfless way and with total soul. Everything is given up to the music at hand, which I believe is the only way you can create music of any depth. I know they will always give 100%; never just going through the motions, but always looking to expand the music without destroying the character of a piece.

Experience has taught me that you can't get anyone to play a certain way if they don't want to or can't feel it. When it comes down to it they are going to play what is in their hearts. So you have to wait until you find the right people to play with you in the way you'd like.

AAJ: Before you hooked up with Matthew Halsall, did you ever consider moving to London, in search of like-minded musicians?

NB: When I was trying to put bands together, I always thought that in London there would be more like-minded players, but I've resisted the idea of moving there for several reasons. First, I've never thought myself good enough as a musician to survive in such a competitive climate. I'm not a competitive person and my approach to music mirrors this I think.

Second, the people I know who have moved to London have been pretty much swallowed up by either the session route or they are "rhythm section" players who get plenty of gigs but don't necessarily pursue their own musical path.

Finally, London never appealed to me as a place to live. I have, in the past, wanted to live in either Paris or Amsterdam but really I'm at home in the English countryside, especially where there are hills. I find it inspiring and it appeals to my sense of calm and simplicity, as well as a strong feeling for nature, all qualities that I value.

AAJ: What are your immediate plans, now that Guiding Spirit is out and the buzz around your music is growing?

NB: I'm just looking forward to doing more playing, to more people in as many different places as possible. I've always wanted to play throughout Europe, festivals or otherwise. So playing farther afield would be great.

Recording-wise, I'd like to try some more expanded groupings, more horns for example. I'd also like to further investigate the possibilities with the kora [West African harp] and the balafon [West African xylophone].

Top 10 Legacy Albums

A mix of jazz and reggae, with a little Motown, here—in his own words—are Birchall's top 10 legacy albums. In no particular order:

Yabby You and King Tubby, Chant Down Babylon Kingdom (Walls Of Jerusalem) (Nationwide, 1976). The music of Vivian "Yabby You" Jackson has been a huge inspiration to me. He often manages to get a very deep, spiritual sound on his records. This particular LP has the vocal tunes on one side and the King Tubby dubs on the other. Tubby was a genius. He was a very subtle and skillful engineer who understood dynamics and development in a piece of music.

Count Ossie Mystic Revelation Of Rastafari, Grounation (Ashanti, 1973). Count Ossie was the man who developed the burro or nyabhingi style of drumming that is played by rastas at grounation meetings. People like Tommy McCook and [trombonist] Rico Rodriguez would go to his musical gatherings and play jazz horns with the drums. This triple LP is a cornerstone of both my record collection and also my musical world. Many of the tracks feature Cedric "Im" Brooks on tenor saxophone. Big jazz influence on this album, there's even a version of a Charles Lloyd tune, "Passin' Through."

John Coltrane, A Love Supreme (Impulse!, 1964). I think one of the reasons that the first part of Love Supreme, "Acknowledgment," has a resonance beyond the regular jazz audience is because of the bass-line. What is termed an ostinato in jazz—a repeated bass figure—is a mainstay of other music, like reggae or funk, and people react to it. There's also the vocal refrain which is something that's very rare in jazz.

Marvin Gaye, What's Going On (Tamla Motown, 1971). The first side of the record is spell-binding. The way the songs segue into one another is a masterful thing in itself, and the sequence of the songs is perfect too. The writing, arranging and, of course, Marvin's vocals are magnificent. A masterpiece.

Albert Ayler, Nuits De La Fondation Maeght Vol. 2 (Shandar, 1970). This was, I think, [saxophonist] Albert Ayler's last recorded work. He reaches heights of intense yet joyous expression here, although in a more reflective way than in his 1960's work. It's incredibly passionate yet very stately at the same time. Cosmic poetry.

John Coltrane, Creation (Blue Parrot, 1965). This LP has 2 tunes from a Coltrane appearance on a San Francisco TV show, "Alabama" and "Impressions" from 1964, and one tune, "Creation," from the Half-Note club from 1965. "Alabama" was the first piece of music that I heard that really seemed suggestive of something far beyond the actual sound of the music. It was the way that Trane held each note and inflected it, as if he was talking directly to you about something very deep and important—though I only learned about its actual inspiration later. And the intensity of the title track is mind-blowing. Trane could keep that level of intensity up for long periods of time but always managed to stay completely articulate and soulful all the way through. To see that band in person at that time must have been unbelievable!

Prince Buster All Stars, The Message Dubwise (FAB, 1974). This is the very first dub that I heard. I was completely taken with the way the instruments were in the mix and then out of the mix, with tape echo and all that space—and spaciness. It was a revelation, an unforgettable moment. Probably this is still my favourite dub LP. The first cut is the deepest.

Frank Wright, One For John (BYG, 1969). The title track of this is still one of my favourite pieces of music. It's very free but hangs together in a very loose way and has a very passionate, soulful expressiveness that had a big effect on me back in the day.

Pete LaRoca, Turkish Women At The Bath (Douglas, 1967). This has one of my all-time heroes on tenor sax, John Gilmore. His solo on the title tune was a big early influence on me, it seems so perfectly logical and impeccably developed and delivered. The album itself has a big Turkish, or at least Eastern, influence to it. Years after discovering it I played for a while with a Turkish drummer, Akay Temiz, and I was struck by the similarity in the arrangements of the traditional tunes we played and the arrangements on this album. I played him the LP and he was knocked out by it. A lot of different music was being done in the 1960s and not all of it was followed up and explored further.

John Coltrane, Afro Blue Impressions (Pablo, 1977). Music from Coltrane's 1963 European tour. This version of "My Favorite Things" is my absolute favorite. Trane plays things on this that I haven't heard him play anywhere else. His statements convey such exceptional joy and beauty that I used to get tears in my eyes listening to it. The band hits such a perfect uplifting groove and sustains it for the full 21 minutes. The tension and inventiveness, from everyone in the band, never lets up.

Discography

Nat Birchall, Guiding Spirit (Gondwana, 2010)

Matthew Halsall, Colour Yes (Gondwana, 2009)

Nat Birchall, Akhenaten (Gondwana, 2009)

Matthew Halsall, Sending My Love (Gondwana, 2008)

Nat Birchall, The Sixth Sense (Sixth Sense, 1999)

Elevator, The Crunch (Hot Dots, 1991)

Photo Credit

All photos courtesy Nat Birchall

< Previous

Bettye Lavette: Interpretations - The...

Next >

Tapestry Unravelled

Comments

About Nat Birchall

Instrument: Saxophone, tenor

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

Nat Birchall

Interview

Chris May

John Coltrane

Pharoah Sanders

Charlie Parker

Isaac Hayes

Cedric Brooks

Roland Alphonso

Sonny Rollins

billy harper

George Adams

Horace Silver

Rico Rodriguez

charles lloyd

Albert Ayler

Frank Wright

Pete LaRoca

John Gilmore

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.