Home » Jazz Articles » First Time I Saw » Modern Jazz Quartet: Softly, As In A Morning Sunrise

Modern Jazz Quartet: Softly, As In A Morning Sunrise

What these four gentlemen brought to jazz and the world of music, out of the careening bebop fury of the early '50's was the sound of elegance.

There is light in The Vanguard, but it's an artificial, blood-stained colored light that seeps out from somewhere behind the ceiling's blackness, coating everything it falls on like a sepia St. Elmo's Fire: Nondescript bar stools. Little one-foot-square tables.

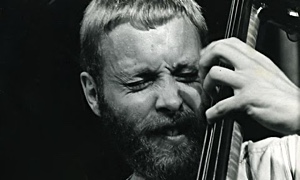

On this particular July Sunday afternoon, it was falling on the dark tailored pinstriped lapels of Percy Heath. It was falling across the shapely wood-carved shoulders of his contra bass, highlighting the instrument's graceful violin shape, its swan's head, the chestnut burls in its dark honey-colored torso.

There in the Village Vanguard's boozy-smelling back space just behind the bar at the foot of the famous stairs that go down from Seventh Avenue, Percy Heath is tuning his instrument. His skin has turned a deep plum color in the bleeding Vanguard light, his left hand flutters at the slender neck of the bass while his right arm reaches ardently across the curved body with the bow producing a softly polished, oak-tinged voice. It's the sound an ancient tree might make during a forest storm, a sotto voce creak that turns into a soft, singing sigh. The dank floor around him resonates with the sound.

He thrums the strings just above the notched bridge, rolling his fingers outward, letting the notes resonate as they escape, moth-like into the surrounding stillness. He walks a few blues-y measures in four-four. And there it is: the unmistakable throb, the exquisitely reliable heartbeat of The Modern Jazz Quartet. Four men that comprise an entire orchestra.

What these four gentlemen brought to jazz and the world of music, out of the careening bebop fury of the early '50s was the sound of elegance. Elegance that swung just as hard as the raucous Count Basie rhythm section, or the leaping schizophrenic Parker-Gillespie-Powell groups. Duke Ellington}} had shown everyone the possibilities for elegance on a large canvas. But John Lewis, Milt Jackson, Connie Kay and Percy Heath had distilled it into a small, white-hot, opalescent fire in a four-man crucible that defined cool, seemingly effortless swinging. Their music had all the headlong push of bop, the tension and release, the dangerous turns; plus the confident, sophisticated feet-on-the-floor veracity and nuance of a perfectly balanced classical chamber group.

There are moments when the MJQ is all about nuance—about the meaning behind the beat, the afterglow of a perfect note bent ever so slightly to increase the tension.

They were "Modern." They were "Jazz." And they were a "Quartet." Four musicians who played, who thought, who pulsed like one. And at the center of that pulse, the bassist. Percy Heath.

They dressed in sedate matching, shadow-colored three-piece suits, like diplomats there to deliver an urgent, possibly even disturbing message in the quietest, most reassuring tones. They stood squarely behind their instruments, piano, bass, vibes and drums in the center of the stage and they played. Their acoustic balance was perfect, honest, with no electronic "compensating" required. When a bass note needed to be let through the curtain of the other instruments, to be louder, to make a point, the other instruments parted momentarily and it emerged in precisely the right place, dropping like a diamond into a velvet glove. Every note they played had that uncompromising exactness. That inevitability. The only possible note that could have been played then and there.

And the Quartet rode on the shoulders of Percy Heath, who, like all good bass players, bore it like an eager workhorse. His contribution was the musical equivalent of charity and of humble support from pure unwavering strength.

I stood a few feet away from the man, letting the sound of his bass notes define the space around us. When he looked up and saw me, a 19-year old college kid just discovering his music, he smiled a little crooked, friendly, smile and went back to his assiduous tuning process. Always the workman.

I had nothing to say, and yet I wanted more than anything to talk with him, to hear him speak, to find out what he could tell me about The Music. I had a million questions and I couldn't think of one. I was here at The Vanguard because I had seen the MJQ a few months earlier "live" on Steve Allen's old Tonight. The Quartet was four or five years old then, just starting to be noticed, like some new constellation appearing unexpectedly in the night sky.

That evening at The Tonight Show, they played "Softly as in a Morning Sunrise" and "I'll Remember April." It was a life-changing moment for me. This was a whole other way to think about music, I realized gradually. It was like discovering a color I'd never even seen before.

It was all still so new to me, I did not even have the language to formulate the questions. I was still too new at jazz to know that Percy Heath had been part of it all since the beginning, since Bird and Dizzy. Since Monk and Bud. He was already in the history books. To me he was simply the bassist with The MJQ, a job so large and important that I could only assume he must have spent his entire musical life focused only on this.

Finally, I manufactured a question simply as a reason for staying there with him in the bleeding light behind the bar at the foot of the narrow, legendary stairway.

"Do you ever play with any other groups?"

He smiled without looking up from his long silvery bass strings. His face was long and sculptured with high cheek bones. His precise hairline and jaw repeated the curve of his bass. It reminded me of an Egyptian mask, or a face carved into the marble on some cornice on a Greek temple. He laughed silently but he did not answer my question. He seemed a little embarrassed by it, as if it would have been some kind of PR faux pas for him to acknowledge that he did, on occasion, stray from the dark monastic brotherhood of the MJQ to play in some more profane context.

I restated my question: " Who else do you like to play with, besides the MJQ?"

His brown eyes darted around the nebulous space where the walls bled into shadows, as if searching for an escape. My persistence had made him uncomfortable but I could not let go of his attention now. I inched closer, hoping to engage his eyes.

At last, too kind, too much a gentleman not to answer, he replied.

"Well," he said finally, "I guess Miles."

This was at a time just before anyone but musicians and astute music critics knew there was going to even be a MILES. Heath used only Miles's first name the way that the insiders who had played among the Giants, always did—"Miles," "Sonny," "Bud," "Diz." "Max." "Percy." There was only one of each.

I had heard the name, but the sound, the revelation that would be Miles Davis, had not reached me yet. Had not, in fact, really happened yet to the planet, but was only just about to.

"Miles Davis?" I asked innocently, proud of my ability to put the last name to the first. Percy Heath nodded.

"You ever make any records with him?" I asked.

Again, the fear of making some kind of P.R. misstep flickered beneath his polite smile, but again, too much the gentleman, he replied. "Yeah. There's one coming out soon called 'Walking.'"

And that was it. More than I had hoped for, actually. I had something now, a small treasure to take away with me. A conversation, albeit only a few sentences long, had happened between Percy Heath, and myself. I took it away with me into the midnight of the Vanguard's tiny angular space, to my miniature table where I waited with my friends for the music to start. For The Quartet to materialize on stage. I did not share the conversation with my friends or anyone but only mentioned in passing that I had seen Percy Heath back there behind the bar.

"What was he doing?" one of my buddies asked me.

"Tuning up," I said casually, giving away not one iota more of my precious exchange with Percy Heath than I had to, keeping it close and private until it became a true part of my slowly expanding musical memory.

And then it was time to hear him play.

< Previous

Tenor Of The Times

Next >

Two is One

Comments

About Modern Jazz Quartet

Instrument: Band / ensemble / orchestra

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.