Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Lenny White: Jazz/Rock Collides Again

Lenny White: Jazz/Rock Collides Again

When that cool, overcast dawn arrived in Bethel, New York, neither the Woodstock Music and Arts Fair's expired permit, nor the rain, mud, and technical problems could have kept Jimi Hendrix and his Band of Gypsys from playing. It was destiny. Believe it.

When that cool, overcast dawn arrived in Bethel, New York, neither the Woodstock Music and Arts Fair's expired permit, nor the rain, mud, and technical problems could have kept Jimi Hendrix and his Band of Gypsys from playing. It was destiny. Believe it. A hundred miles south on that same morning of August 18, 1969, Miles Davis had gathered the four other members of his famous quintet at his New York City home for a short rehearsal: drummer Jack DeJohnette, saxophonist Wayne Shorter, bassist Dave Holland, and pianist Chick Corea. He'd also invited the 19 year-old drummer from saxophonist Jackie McLean's band, Lenny White.

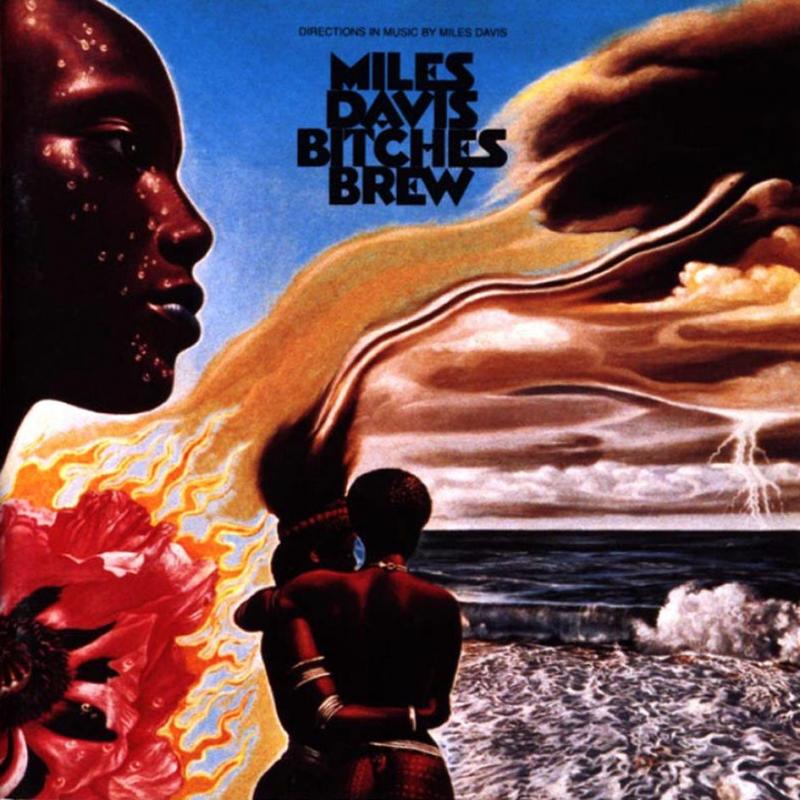

Talk about an alignment of cosmic forces. While Hendrix was mesmerizing those assembled on the historic hill at Max Yasgur's dairy farm, Davis' invited guests were running through a new composition called "Bitches Brew," the eponymous title tune for an album that would soon rock the jazz world, ready or not.

A few months later, Lenny White was Freddie Hubbard's choice for the drum kit when he recorded one of the next important jazz/rock entries, Red Clay (CTI/Columbia, 1970), along with Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Joe Henderson. It only takes listening to the first 60 seconds of White's drumming on the title track to understand Hubbard's choice. The recording, undoubtedly among Hubbard's finest as a leader, is due in no small part to the gyroscopic centering influence of the rock-based rhythms provided by the young drummer.

After he'd gone to play in the Bay Area, White finally saw a copy of Bitches Brew (Columbia, 1970) in a record store window and knew the exciting sensation of seeing his name on a Miles Davis album cover, when Chick Corea called him from Japan. Corea was touring with his new band, Return to Forever, and wanted to know if his friend from those infamous sessions was interested in joining him and bassist Stanley Clarke for an upcoming engagement at San Francisco's Keystone Korner, as the group's drummer, Airto Moreira, was returning to New York with his wife, singer Flora Purim, and their newborn child. White was indeed available, and jumped at the chance to play what he anticipated would be great fun, and what he has since described as "fantastic music... really great." On the last night of that fortuitous gig, three other local musicians sat in with them: guitarist Barry Finnerty, plus two players who would soon be offered spots in Corea's newly formed electric edition of Return to Forever—ex-Santana percussionist Mingo Lewis and guitarist Bill Connors. The drum chair was offered to White.

Who respectfully declined. He knew how great the possibilities were but liked the band he was playing with, the large Latin rock band Azteca. Formed by ex-Santana percussionists Coke Escovedo and Pete Escovedo, this talent-rich group at one point employed 17 musicians, including bassist Paul Jackson, trumpeter Tom Harrell, and ex-Santana guitarist Neil Schon. The group had recorded its excellent debut, Azteca (Columbia 1972), with a set of tunes that has since assumed legendary status with Latin jazz/rock aficionados as a monument standing alongside works like Carlos Santana's Abraxas (Columbia/Sony 1970.)

Azteca, Circa 1971: Lenny White, far left

Azteca, Circa 1971: Lenny White, far leftA short while later another juicy offer came his way, this time from Herbie Herbert, who was managing some groups around the Bay area and had an idea for a new band he wanted to form with Neal Schon and bassist Ross Valory. White accepted the invitation and rehearsed with them, but when Herbert sprang the question, he said he had to decline. White's accountant may never forgive him for not taking the job with the band, soon to be called Journey, but as the poor bean-counter must know by now, Lenny White has always made the lightning strike by following his muse.

By then he'd gotten another call from Chick Corea. On their return to New York, Corea had hired his old friend Steve Gadd, but despite Gadd's talent and well-regarded technique, he was not a perfect fit. What was needed for this band was jazz sensibilities plus rock and roll power, precisely the kind White could supply. Corea had new material ready to record, and wanted the drummer he had offered the job to in the first place. Stanley Clarke also knew White's wide range of capabilities from the work they had done together in Joe Henderson's band. This was electric jazz that needed rock's rhythmic concussion and thunder. And Bill Connors was starting to play like he wanted to un-seat John McLaughlin from his throne. Was he interested?

Lightning strikes were coming fast, as White stood at a crossroads. Personally, artistically, opportunities were everywhere. Professionally, he stood at the precise point in time and space where jazz and rock were converging at a rapid rate. It was unlikely that Chick Corea had spent much time listening to The Beatles, or that Neal Schon had heard Kind of Blue (Columbia, 1959) more than once. What was important, however, was that White had.

Soon after arriving in New York, White joined Corea, Clarke and Connors in the studio and they recorded the groundbreaking Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy (Polydor, 1973.) Together with Mahavishnu Orchestra's Birds of Fire (Columbia, 1972), these two revolutionary recordings invaded the airwaves and ushered in the dramatically hair-raising, powered-up era of jazz/rock and progressive rock.

Lenny White has been a lightning rod ever since.

From that moment on, White has spent his career in jazz at the center of the storm. Wherever he's gone he seems to have helped chart new territory and illuminate new paths. On Anomaly (Abstract Logix, 2010), his first CD of personal material in over ten years, he's done it again.

Chapter Index

Anomaly

Anomaly All About Jazz: Tell me about your new CD.

Lenny White: It's interesting, because I went back to what we were doing back in the '70s. I'm just trying to capture what made me feel good back then—how radio used to sound to me. I'd turn on the radio and I'd hear a James Brown track, and then they'd play Led Zeppelin, and then they'd play Miles. Then they'd play a lot of different kinds of things.

AAJ: When you did this album, you did representative tracks because you've done a lot of different things. I mean, it's not just jazz-rock. You're one of the premier funk guys of all time.

LW: I got some of that! Mike Clark and I did a track. We just went in and improvised, and we had everybody play around with what we improvised. What's deep is that it's based on an old Big Sid Catlett drum lick, but it's funky. It's called "Catlett Out of the Bag." Mike Clark put the name on it. It's pretty slick. And I didn't go back in and correct it; it's raw, and man, we had a ball. It was really fun doing it.

AAJ: I'd rather hear a live recording than anything.

LW: Yeah, well, this was straight up. And I haven't put out a personal musical statement in ten years. I've produced records, played on other people's records...and the other thing is that I've been making a lot of "jazz" records lately. So I wanted to not do that. I wanted to do something that was just making some music. And it was fun.

AAJ: What else is on the record?

LW: I'll put it to you this way: the name of the album is Anomaly. It's my musical statement right now, and I hope people like it. If they don't, I understand. But I just wanted to make my musical statement right now.

AAJ: Your music tends to be pretty personal, anyway.

LW: Well, any artist's music is personal. It's a collection of their life experiences. So I went back and got some old compositions that I had done with my Astral Pirates band. And there's a composition from the guitarist that plays in my band, Tom Guarna. And George Colligan, who played in the band and has a couple of compositions, and I have a composition by a great guitarist, David Gilmore...not Pink Floyd's David Gilmour. I wrote all the other tunes.

Actually, there's one piece that is an adaptation from my opera. It's a spiritual called "The Wait Has Lifted the Weight." See, when Obama was elected, it caused a big paradigm shift. But for black people in America who have been waiting for something to happen, or waiting for some credibility, it's not the end-all, but now they have to be held accountable. Because things have started to change. Martin Luther King's dream has started to become a reality. It's not [finished] yet. But at least there's a shift. So we've been waiting, as black people, we've been waiting, and there's this weight that's been holding us down. So now that this has happened, it's a beginning. It's like, you're peeling it off, and so this wait has lifted the weight.

That [brings up] the other thing. The record label. Now, I'm doing my own, I'm doing it myself. It'll be distributed by a label [Abstract Logix], but this is mine—I paid for it. So I'm doing what I want to do. We listened to all kinds of music. And I thought that it was about time for me—well, I think I do that all the time, but I haven't made a record in ten years. But I thought that in my project I would show all of my influences, where all of my influences come from, rather than being musically myopic. I know people could listen to it and say, "Oh, what? This is all just rock and roll!" But there are things in there that, from a stylistic standpoint, are like Philly Joe Jones and Art Blakey playing a rock beat.

But what I don't want to have happen is for people to be misled. Being a jazz musician and having a particular work ethic and commitment about representing that music, and that music being, to me, the highest language spoken on the planet, you'd have to have an affinity for just more than that music. You'd have to have an affinity for all kinds of music. And if you get to a level where you can create like the great masters of jazz created, you could play any kind of music, because that discipline and that perspective on music in general would help you play any kind of music. So, for me, when you hear this music and you say it's rock... yeah, it is, but it's made by a jazz musician.

And so, however you want to call it, it's not fusion, I'll tell you that. That ain't what it is, man, because I'm not playing licks. Fusion, to me, has become this thing that's really cute. They have these little 10" splash cymbals, phsssw. This [Anomaly] is balls-to-the wall, a knock-you-down band. This is what it is. You like it? Cool. If you don't, yeah, okay.

AAJ: I never thought that I'd pick "Water Changes Everything" as my favorite track, but it's a strong contender, just because you did something unusual with it. Politics and political discussion can be so divisive that people just avoid it, because it makes enemies out of friends and turns things sour. But "Water Changes Everything" is interesting because it de-politicizes a very political thing, and just says something like, "You're part of the human race."

AAJ: I never thought that I'd pick "Water Changes Everything" as my favorite track, but it's a strong contender, just because you did something unusual with it. Politics and political discussion can be so divisive that people just avoid it, because it makes enemies out of friends and turns things sour. But "Water Changes Everything" is interesting because it de-politicizes a very political thing, and just says something like, "You're part of the human race."LW: Well, it's not political. What we're talking about in "Water Changes Everything" isn't political at all. I was in Europe and I was watching CNN, and in actuality, the program was about getting clean water, clean drinking water to everybody on earth. And the discussion came down to the point where the commentator asked the principal in the interview, he said, "Well, what do you think it would cost for us to be able to get clean drinking water to everybody on earth?" And ironically, at the same time—I'm watching this, and at the same time he's about to give the answer, that crawl that runs on the bottom of CNN's screen—all news broadcasts have the crawl—it says that one major car company was buying another major car company for ten billion dollars. And [in the same moment] the answer out of the principal interviewee's mouth was: "ten billion dollars." I thought that that was so profound.

This is a right, to be able to have clean drinking water. I mean it's a human condition. Everybody should be able to have clean drinking water. And that's not the case. There's a charity that builds wells in Africa—for people that don't have clean drinking water to actually have clean drinking water. And a friend of mine, one of the co-writers, came to me and said, "You know, there's this charity. We should do something for them," so I had a piece of music, and I went to their site and got some information, and along with another friend of mine, we wrote some lyrics about it.

AAJ: That's Sammie Williams?

LW: Mm-hmm. And Chris Williams and Rennie Hurst—the other guys—and basically what we were saying is that this simple thing, which is clean, running water is pretty much taken for granted in industrialized nations, and we live on a planet that's two-thirds water. And there are people that don't have drinking water. That doesn't make any sense.

And so, it wasn't political, what we were saying. We were just saying a really simple thing. Water changes everything. I mean, our bodies are filled with water. And all these industrialized nations, and all the money and wealth that's in the world, as a global community... I mean, for the survival of the species, that should be a simple thing—to have everybody have clean drinking water. Simple.

AAJ: Well, I just dug it a lot because it's political in the sense if you look at the word politics, and it's the relationship of human beings with other human beings...

LW: Well, that's not my relationship, that's not my definition of politics. My definition of politics is the manipulation of people.

AAJ: Right. So it's definitely not an attempt to do that. But I thought it was kind of elevating to just consider, for a minute, what it takes to actually make sure everybody has clean drinking water on the planet. It can't be that it's such a monumental task. If you can buy a car company for ten billion dollars, it can't be that hard.

LW: You know, cruise ships have the mechanisms—they're floating on sea, which is salt water— they have the mechanisms on each one of these cruise ships to distill at least a million gallons of water a day and make it into drinking water. A cruise ship has three thousand people on it. But that ability to do that, that technology [exists] to do that, and then you have a billion people without clean drinking water. I just asked some questions; that's all I'm doing.

Freddie Hubbard (left) and Lenny White (right), 2006

Freddie Hubbard (left) and Lenny White (right), 2006AAJ: I was just envisioning coastlines where you wouldn't need to worry about pumping oil because you've got these water treatment things set up. And everybody gets clean drinking water.

LW: Yeah. Sometimes we have to remind ourselves that this is the 21st Century, because when you look outside, you don't know that.

AAJ: Back to the disc, Anomaly is pleasant, it's satisfying and it works on all kinds of different levels. You've taken all that sophisticated musicianship—I mean, you've assembled a band that has got so much talent it's hard to document it all, this is a group of very, very good players, spirited players—and taken an art form, which is relatively simple and turned it into a new thing, a new variation.

LW: Well, I'm actually glad that you got that. But, again, my intention was to make some music—see, nothing is done to the max without a purpose. And my purpose was to get some hard-hitting music out, and I wasn't intent on playing a whole bunch of drum solos. That's boring to me. I was intent on getting some good music out. And to have it sound good. And for it to be an honest and clean intention. Simple. That's what my intention was.

Now let's see if we can get about 50,000 more people [to listen to it]. You put a project out and you want it to be successful. Success has a lot of levels of meaning. It's successful because I did it and put it out, and people are going to hear it. That's a successful level. But I'd like for it to be successful on another level, that it could be a positive median line, where people say, "Wow, the bar's been raised and we need to hear more music like this. And if the number of people that feel that way is amplified to be a pretty big number, that's another degree of success. So, it's multi-tiered.

I would like for it to be a benchmark where people say, "Aw, man, I haven't heard a record like that in awhile." Let's be positive about what it is that we do, and not have to worry, because getting played on the radio? Well, what's the radio? This is about music.

Bitches Brew

AAJ: : I don't know a lot about you before Bitches Brew. That's the first time I saw your name on something.

Lenny White with Bitches Brew platinum record

Lenny White with Bitches Brew platinum recordLW: Well, it's the first time my name was on something. That was a real stamp to qualify my being part of a movement, or being a working, recording musician, at 19.

AAJ: Miles Davis looks pretty good on your résumé. How did Miles hear you and pick you?

LW: New York was...well, it still is a mecca. Any qualifications come from being able to make it in New York. Back in the late '60s/early 70's, living in New York, I got a chance to see everybody, and all of us young musicians had aspirations to play with Miles Davis, because Miles was the epitome of hipness, and it gave you a certain credibility that you couldn't get anyplace else.

And so I'd been playing around, and word got out that I was one of the hot, young guys. I had done some sessions with people and the word got out, and I played with Jackie McLean. Jackie was a great jazz saxophonist in his own right. He was friends with Miles Davis for years. And Tony Williams first played with Jackie McLean, and Miles heard about him playing with Jackie. And so Tony went from Jackie to Miles.

AAJ: So, it was a natural progression?

LW: Well, no, but what happened also was that Jack DeJohnette had also played with Jackie McLean. And after playing with Jackie, Jack, of course, played with Charles Lloyd and other people, but then he went and played with Miles. So when I got to play with Jackie, everybody said, "Oh, man, you're next, you're going to play with Miles because you got to play with Jackie McLean!" So there was a lineage. And of course I aspired for that to happen; it was a dream.

But I played around, playing gigs around New York and Queens, where I'm from. And I played this gig one night with two drummers. It was an avant-garde kind [of thing], and Rashied Ali was the other drummer. And there was a trumpet player who was a friend of Miles, and he was playing, so when the set was over, he said, "Man, has Miles ever heard you play?" And I said, "I don't think so!" And he said, "I'm going to tell Miles about you!" And I said, "Yeah, right, whatever, sure."

And the next thing I know, I get a phone call. Miles is calling my house, and my mom answered the phone. And you know, Miles had this raspy voice. He said, "Akhhhhh," and my mom said, "Who is this? Man, if you don't speak up, I'm hanging the phone up," And so then she handed me the phone, and I got an opportunity to talk with him. He asked that I come to his house and rehearse. So I went there. All he wanted me to bring was a cymbal and a snare drum.

And I went. Jack was there. And Dave Holland, Wayne [Shorter]. I think Chick was there, too. And we rehearsed the first part of "Bitches Brew." Do do doo, do do doo, diddle do, do do doo. Doooo, da. Daaa da. Phswww." And he said, "Okay, be at CBS Recorders at 10:00." It was kind of historical, I believe; if not exactly the weekend, then the same week as Woodstock [That first recording session at Columbia's Studio B occurred the morning of Tuesday, August 19th, 1969. Less than 24 hours after Jimi Hendrix concluded his iconic performance, Miles Davis, Lenny White and the others were recording what would ultimately be Bitches Brew]. And then we recorded for three days. From 10:00 to 1:00. Three days. That's it. Juma Santos played percussion. Don Alias played percussion. Jack DeJohnette, myself, Dave Holland, and Harvey Brooks. Bennie Maupin, Joe Zawinul, Chick, and Larry Young played on "Spanish Key." John McLaughlin, Wayne and Miles. That's it. So all the people that tell you that they were on the Bitches Brew session, no. That's who was there.

Tony [Williams] was still around, and Tony was the guy who actually got it rolling, I mean, without him there would be no Bitches Brew.

AAJ: When you talked to Miles, did he ever talk about what Tony was doing with Lifetime?

LW: He wanted [the new recording] to be Miles Davis featuring Tony Williams' Lifetime. And Tony didn't want to do that. So Miles got John [McLaughlin] and Larry [Young], and put them on.

From left: Tony Williams, Lenny White, Jeff Ocheltree

From left: Tony Williams, Lenny White, Jeff Ocheltree AAJ: [laughs] There's a thing about a bandleader—there are different styles of bandleaders. I've heard, from a couple different guys who played with Miles, that he didn't say much, that one of his biggest strengths as a leader was not what he made people do, but what he let them do. Chick [Corea] tells the story of his first gig with Miles, when he filled in for Herbie Hancock. They only met for a minute in the hotel lobby before the gig, and I think the entire conversation consisted of one sentence of advice from Miles: "Just play what you feel." It seems he was more interested in finding the right guy and then saying, "Okay, now, you do what you want to do, and see how we can fit that in with what we're doing."

LW: Well, that's true. But I know, when we did the Bitches Brew record, he did give me some direction. He said to me, "Jack's going to play the rhythm, and I want you to play all around it. You play whatever you want to play, but I want you to play around it." And for me, that was the beginning. I've done a lot of different things with more than one drummer, and I try to create the image, the audio image, of one guy with eight arms, as opposed to two drummers. And I think it comes from Miles saying that to me. He said, like, "Let Jack play the rhythm and I want you to play all around it, and make it do this and spark."

And it was really cool, you know, to give this young guy this opportunity to do that. Because he could have told me, "Play the rhythm and let Jack play all around that." Chick told me a story, too. He said that he got into the band and he went to Wayne and everybody, and just asked what changes they were playing on these tunes, and nobody would tell him anything. And Miles would never say to him what the changes were. And he tried to find out the changes. And so then he just decided to work within the framework and do whatever he heard. And Miles said, "Yeah, that's what I really wanted—that's why I didn't tell you what to play, because I wanted to hear what you would do with the music, and take it someplace else."

AAJ: That's how a Zen master does things.

LW: Even as a director of movies' I'm quite sure Martin Scorsese would say to Robert De Niro, "Well, here's the idea." As a matter of fact, Martin Scorsese said something to that effect. In Taxi Driver [in the role of the man in the cab spying on his wife], Scorsese gets into the cab, and Robert De Niro's driving the cab, and he's [Scorsese] supposed to look up and see his girlfriend up there. So he said that he got into the back seat and he was waiting for Robert De Niro to give the line, and he kept waiting, and waiting, and waiting, and he said, "You're supposed to give the line!" and he [De Niro] said, "Well, no, Marty, when you get here, you have to make it convincing." He [Miles] didn't have to say anything with certain guys. Certain musicians or actors will bring to the table something special to make the scene or the music emanate. And if you have to tell somebody what to do, it's one thing. But if you just give them minimal direction and let them go on and create something, most of the time you get something special.

AAJ: But you can only do that with somebody who's got it to begin with.

LW: Well, you do that with people that are in tune to whatever vision you have. You know, you pick people that have vision. Or somebody that you'd say has the same kind of viewpoints on things. You pick those kinds of people. And then again, you could have situations where you pick somebody that has the opposite [viewpoint] of what you would think, because that's what you want to get. It's about what you want to get as a producer or director, you know. You pick people that way. And usually it'll work to your advantage.

AAJ: I heard a story that during the recording of Bitches Brew, Miles was acting a lot like a movie director does when you're doing improv. He would just do the setup and he would get a group of guys...

AAJ: I heard a story that during the recording of Bitches Brew, Miles was acting a lot like a movie director does when you're doing improv. He would just do the setup and he would get a group of guys...LW: We were in a circle. We were actually in a circle. And we'd play, and Miles would stop, and start up the rhythm again, and he'd point to John. And John McLaughlin would play. And he'd stop, and he'd point to Wayne Shorter, and Wayne would play. That's how we—if you listen to Bitches Brew, when you hear the points where someone plays and there's a soloist, and then it stops, and then it starts up again, that's what was happening.

AAJ: That stop time thing gives it such a dramatic push that you have to be paying attention to know what's happening with it. It's not background music.

LW: You could think of it as... if you have an ensemble of actors and the scene is to have a conversation with all of the actors, and then you stop and let one of them have a soliloquy, and then the other actors [say], "Yeah, right!" and "Tell me more about it!" and "Tell me more!" And it happens, and that's what you get. That's the way it was recorded.

Improvising is a part of life. It just so happens that musicians use their instruments to improvise. Boxers do that every time they box. Baseball players do it every time they play baseball. Not necessarily politicians, because they have their speeches, and they don't really go past— they're pretty cut and dried. But then again, great politicians are able to improvise when the crisis comes. When crises arise, they're able to improvise for the betterment of everybody.

A Jazz-Rock Documentary Film

AAJ: You are doing a documentary film on the jazz-rock movement, late 1960s through the 1970s.

Return to Forever 2008, from left: Al Di Meola, Lenny White, Stanley Clarke, Chick Corea

Return to Forever 2008, from left: Al Di Meola, Lenny White, Stanley Clarke, Chick Corea LW: Yeah, it starts around '67 and then I think it goes maybe [to] '81, '82. And then it started to change. The documentary that I'm trying to put together focuses on what I consider to be the six seminal groups of jazz/rock, which is Miles, Return to Forever, Mahavishnu, Weather Report, Herbie Hancock's Headhunters and Tony Williams Lifetime. And of those six bands, there were at least one or two representatives on the Bitches Brew sessions. Every one of those bands had the seeds planted in those sessions. And those bands were—I think that Bitches Brew gave the movement a face. And a sound. And then, from that, these bands took that direction and made it, well, personalized it, because then people started to follow those particular bands. And the fan base grew because you had six options as opposed to one; because you had six sets of fans and it became, you know, a thing, for about ten years.

There was the sophistication harmonically, and somewhat rhythmically, of jazz music, the volume and power of what rock music was. I don't know whether it was egos that got in the way, but it was such a viable movement, and that was really one of the things—I mean, there were some absolutely virtuosic performances during that time period with some unbelievable artists, and nobody talks about it.

AAJ: That's why we have recordings. You can almost be there.

LW: But you know, you're talking about 1969 with Woodstock. That's 40 years ago now. And that was a real big thing, Woodstock. But it's the rock that's talked about, and this other movement was happening also, that nobody knows about. The other thing is that Woodstock basically was performances that were music with vocals. Santana wasn't. But most of the other performances were vocal. Jimi Hendrix did some things that were not vocal.

But just think about that. Everything else was vocal. At the same time this was happening, there was this other instrumental movement going on that has, to this point, taken a back seat and now is almost forgotten, and this was music in the second half of the 20th century, which... is jazz. When Ken Burns did Jazz [documentary television series], it stopped around 1960. And there was a great deal of music that happened after that, that was jazz music. It had the same sensibilities, the same creative process. That hasn't been talked about.

AAJ: There was a turning point for you and the Return to Forever band, a concert in Central Park in New York City.

LW: Well, that was a change. That was a big change. Central Park was a big change to me, because we had been playing, and we had been gathering a good following. We had opened for some pretty big rock bands, playing our music, and there was some aversion to that, to put it mildly. I remember playing with Return to Forever opposite either Mountain or Leslie West and the Wild West. And [while] we were playing our music, the kids in the front row were going [demonstrates by holding up both hands, middle digits defiantly extended.] But we continued to play what we played. With conviction. But when we played Central Park, the Wollman Rink held about 6,000 people. It was outdoors, and we started to play and the fences started to come down. It was like Woodstock, where you saw the people coming in, and they just said, "Okay, well, just let everybody in."

LW: Well, that was a change. That was a big change. Central Park was a big change to me, because we had been playing, and we had been gathering a good following. We had opened for some pretty big rock bands, playing our music, and there was some aversion to that, to put it mildly. I remember playing with Return to Forever opposite either Mountain or Leslie West and the Wild West. And [while] we were playing our music, the kids in the front row were going [demonstrates by holding up both hands, middle digits defiantly extended.] But we continued to play what we played. With conviction. But when we played Central Park, the Wollman Rink held about 6,000 people. It was outdoors, and we started to play and the fences started to come down. It was like Woodstock, where you saw the people coming in, and they just said, "Okay, well, just let everybody in."And I was like, "Wow! There's no singer, and we're playing this pretty heavy music with [a lot of] notes, going here and there, and it was pretty virtuosic. And people loved it. And I said, "Man, this is different. This is a different point right now. At this point what used to be isn't what it is." It's "Now, what is it going to be?" I'm putting that on my Facebook page today. "What used to be is not what it is. What is it going to be?"

You've got to understand; what I'm talking about is not fusion, it's jazz-rock. It's a totally different thing. And what's happened, it's morphed into this thing called fusion. And I don't particularly think that what it's morphed into is like it was. What is considered to be fusion today is not what we're doing.

But, the thing is, that I'm not vilifying it. But I got heavily questioned about a statement that I made on my website. I said that fusion [jazz-rock]—I was calling it fusion at that point—was dead. And I said that because, when we were doing the music, it was vibrant and it had a presence within the industry. If you don't have a presence in the industry, then the industry doesn't acknowledge that it's viable. I qualified it [my comment] by saying that there are people that are playing the music, and not only that, it is great. But it doesn't have the presence in the marketplace. In order for something to be credible, it has to have a presence, or else it's not acknowledged. Jazz gets acknowledged, because it's been here for a long period of time and it has a great legacy and it's a bona fide art form. But if you look at it in terms of relevance in the music industry, it's not relevant. But it's not the artists' fault.

So I was qualifying it from that standpoint. And what I said was that one of the seminal bands needs to get back together, and give some credibility towards a movement. So that's the way I was trying to qualify that, because I'm still asked about it.

AAJ: Well, that's not any different than anything you've ever said. I guess people who would have said it were just not listening very close, because—

LW: Well, people don't listen, period. That's always been a problem. People hear words, but don't listen to what they actually mean, you know? It's talking heads. You see it on the TV all the time.

One of the big problems that I have with how our music is perceived is that a band like U2, or an artist like Amy Winehouse, are, in their own right, great artists, and they affect people positively, but there's such a disparity between what they do and how it's talked about, and what we did and what I do, and how it's talked about. [The rationale is that] because I don't have anybody singing, what I do is not as relevant as what they do. Back in '75—when there was a band [Return to Forever] that was playing instrumental music and people tearing down the fences coming in to see this, and there was nobody singing—what I did was, I thought, pretty relevant. Plus, the people that were in the audience, who are now famous actors and politicians—who have shaped how people think and what people do—they were affected by what I did. So how come my music is not as relevant as any... as U2's music? I'm not saying that U2's music is not relevant.

But what I have a problem with is the disparity between what is deemed relevant and what is not. It's much more of a difficult task to move someone musically without the crutch of a lyric which explains the emotion. So you have to be very, very well-tuned and in tune with what it is you're doing so that you can communicate that to the audience. And if they get it, they really get it. They really get what it is that you're doing. They get the commitment. They get the positive energy that you are giving off. And that's a special thing. And I think that should be acknowledged and recognized.

But what I have a problem with is the disparity between what is deemed relevant and what is not. It's much more of a difficult task to move someone musically without the crutch of a lyric which explains the emotion. So you have to be very, very well-tuned and in tune with what it is you're doing so that you can communicate that to the audience. And if they get it, they really get it. They really get what it is that you're doing. They get the commitment. They get the positive energy that you are giving off. And that's a special thing. And I think that should be acknowledged and recognized.That's why I kind of qualified what I was saying. As an artist, what I don't want to do—I'm not one to say "Your art is less relevant than my art." What I want to explain, is that I have a problem with the disparity. And it's not me saying that, it's the people who write about it, saying that. They say, "This band is the greatest band of all time. Blah blah blah blah blah." But how can you judge that? How can you say "This band is the greatest band of all time"? That band doesn't do everything better than every other band. So this thing about the "best" and the "greatest"—that's something that I really don't buy into.

Now what I do buy into is the fact that I personally have had artists and bands and music that have influenced me from a personal standpoint more than something else. But I can't say this is any more relevant than that. I can only say from a personal standpoint, "I like this more than I do that, and I think that's more relevant because it affected me this way." That's the only thing that I can say about that. But when you put this on a big, grand scale...

Musicians need to take the music back. Musicians never have control over the music industry, because it's an industry. And all industries manufacture products. But as musicians, we are a real, integral part of making this music. When you think about a song like "Rosanna" [a song written by David Paich for the band Toto, winner of the 1983 Grammy for Record of the Year], it is a great pop song, but it has all of these other elements around it that really qualify as great musicianship. You know, The Rolling Stones,The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, Doors Wide Open, whoever you want to say, when pop music was king like that, musicians were involved. There were solos on those records, and you could hear musicians playing.

Then it switched up. Tracks with singers became more prevalent than [recordings relying on] musicianship. So when you get a Britney Spears record, there might not be anybody playing music on it, playing any instruments on it. Might not. But that kind of music has taken over and is much more prevalent than musicians' music. The one time every year you can hear musicians is at the Grammys, because what you see is people playing live, most of the time. But you don't see any non-vocal music represented at all. So that's what I'm saying, that I would like to have musicians take back the fact of playing music being the main thing of the industry. I don't know if that's going to happen, but I would really love to see that happen.

Then it switched up. Tracks with singers became more prevalent than [recordings relying on] musicianship. So when you get a Britney Spears record, there might not be anybody playing music on it, playing any instruments on it. Might not. But that kind of music has taken over and is much more prevalent than musicians' music. The one time every year you can hear musicians is at the Grammys, because what you see is people playing live, most of the time. But you don't see any non-vocal music represented at all. So that's what I'm saying, that I would like to have musicians take back the fact of playing music being the main thing of the industry. I don't know if that's going to happen, but I would really love to see that happen.Puff Daddy has a show on TV called The Making of a Band, and no one plays an instrument. It's kind of deep, man. Even the hip hop artists, if they studied their craft for ten years and they reached a particular level that's a real creative and positive level, and then punk music comes along, and nobody's adept as hip hop artists are, how would they feel? You know, they spend ten years developing their craft, and then something comes along where they're deemed no longer relevant. How would they feel? It's something to think about. As musicians, we create and play music. But music has become very disposable. And that's a big problem to me. It's used to sell things, as opposed to really being art and enjoyed. And I say this on a general level. I don't say anything that's an absolute. Nothing that I've said is absolute, because I don't want somebody to say, "Oh, man, he said that." Cancel. Forget that. I'm not talking in absolutes. I'm talking generally speaking. I'm talking about how I'm affected and how I see it affecting people. So from that standpoint, if anybody wants to have an argument with me about that, we can. But I am not saying what I say is for you, I'm saying it's for me.

< Previous

Lost in a Dream

Next >

Anomaly

Comments

Tags

Lenny White

Interview

Carl L. Hager

United States

Jimi Hendrix

Miles Davis

Jack DeJohnette

Wayne Shorter

Dave Holland

Chick Corea

Jackie McLean

Freddie Hubbard

Herbie Hancock

Ron Carter

Joe Henderson

Return To Forever

Stanley Clarke

Airto Moreira

Flora Purim

Barry Finnerty

Bill Connors

Pete Escovedo

Paul Jackson

Tom Harrell

Carlos Santana

Steve Gadd

john mclaughlin

The Beatles

Mahavishnu Orchestra

James Brown

Led Zeppelin

Mike Clark

Sid Catlett

Tom Guarna

George Colligan

David Gilmore

Philly Joe Jones

Art Blakey

Chris Williams

charles lloyd

Rashied Ali

BENNIE MAUPIN

Joe Zawinul

Larry Young

Tony Williams

Weather Report

Headhunters

The Rolling Stones

Joni Mitchell

Van Morrison

The Doors

Charlie Parker

John Coltrane

Michael Jackson

Concerts

May

25

Sat

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.