Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Joe McPhee: Artistic Sacrifice from a Musical Prophet

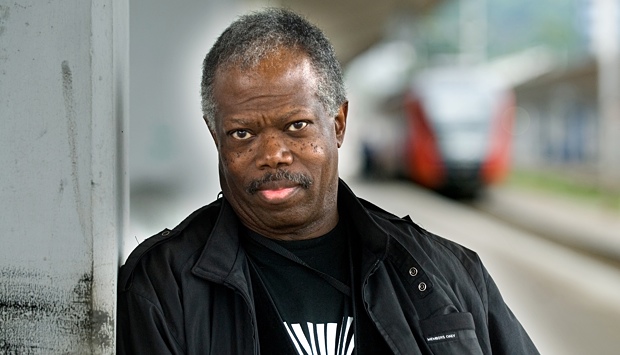

Joe McPhee: Artistic Sacrifice from a Musical Prophet

To imagine an artist that could create from aspects of romanticism, abstraction, impressionism, modernism, realism, futurism or surrealism is to have a better understanding of McPhee's sound landscape. The most creative music lies between the known and the unknown, yet McPhee always pushes towards the spheres of the unknown; his music always begins from a set of values, along with an unorthodox attitude that intensely penetrates from ground zero, every single time. He paints and expresses sound in real time, and the complexity of his art form makes it unlikely to gain many listeners from the shallow depths of revenue-driven pop culture—far from it.

Artists like McPhee are not motivated by money because it doesn't exist here; they create because there is no choice if art is going to survive. It is a passion and it is a sacrifice, and there are no compromises...at any level.McPhee's Nation Time (CJR, 1970), Underground Railroad (CJR, 1969), Pieces of Light (CJR, 1974) and Trinity (CJR, 1971) define a period of time, and will forever stand as monuments in the era of civil rights. These are pieces of music with critical artistic values that represent what it is to express freely, while in the shadows of oppression. It is art expressed in all its glory and greatness, and McPhee is its prophet.

All About Jazz: Let go back to your roots.

Joe Mcphee: My father was born in the Bahamas, on the island called Exuma, and he came from a very British background. He ended up working for a Greek sponge fisherman who taught him how to speak Greek but also taught him how to run a business, how to keep the books, et cetera. He was really amazing.

But my father left Exuma in 1927, at the age of 25, because he wanted to become an American citizen. He had hoped to join an Army band in Arizona, but at that time, the military was segregated. When he finally did arrive in the United States, the band had already disbanded, so he was stuck in Florida. But it's also where he met my mother, who was from Nassau.

I had the opportunity to take him back to Exuma in 1970, and that was his first time back home since 1927. And at that time, the Bahamas were just about to get their independence, and he couldn't quite understand the concept of not having a king and queen.

My mother's maiden name was Cooper, and her uncle was Alfonso Cooper, who was the leader of the Savoy Sultans. Grachan Moncur who was a bassist in The Sultans was also the father of Grachan Moncur III, the trombonist. He and Alfonso were half brothers and had the nickname "brother," and Al [Alfonso] Cooper, the clarinetist and alto player, was the leader of the band. They were a jump band and the house band at the Savoy Ballroom in New York, and they were also the band that everybody had to go through. If you were a player and came to New York, you had to go through the Sultans. They played between 1937 and 1946, and they were really something.

I had the opportunity to interview Alfonso in 1970 and was hoping to have it published in Cadence Magazine. As a result, I took along a tape recorder to capture the conversation, but became so caught up in the stories of what it was like traveling the "Chitlin Circuit" that I forgot to turn on the tape recorder. Their food was placed on trays, outside on doorsteps, while [they were] being treated like dogs.

I had the opportunity to interview Alfonso in 1970 and was hoping to have it published in Cadence Magazine. As a result, I took along a tape recorder to capture the conversation, but became so caught up in the stories of what it was like traveling the "Chitlin Circuit" that I forgot to turn on the tape recorder. Their food was placed on trays, outside on doorsteps, while [they were] being treated like dogs. Unfortunately, it wasn't long later that Alfonso died. But I was reading an interview with Grachan Moncur in Cadence Magazine a few years ago, and he, too, had an interview with Alfonso and also forgot to turn on his tape recorder. [Laughs.]

However, I did get an interview with Panama Francis, as he and my father were close friends. When Panama was a kid, he wanted to play drums with the Savoy Sultans, but he was too young, and they chased him away. Eventually, he formed his own version of the Savoy Sultans, and they played for years with some of the original members.

He also came to visit my father in 1993, and I was able to videotape their conversation. And Panama told me he was writing a book on how jazz developed on the East Coast, which was very different from what came up the Mississippi because of the Cuban influence. But it hasn't really been documented, not really.

Additionally, the music of Dizzy Gillespie and the Afro-Cuban thing is a lot closer to what Panama was talking about, but it isn't well documented, either. And, unfortunately, Panama died a few years ago, so I'm not sure what happened to his book.

AAJ: What about your own music roots?

AAJ: What about your own music roots? JM: I am thinking about how I felt the first time I heard John Coltrane's, "Chasing the Trane." I worked in this auto factory on second shift, and the moment I got out of work, I would turn on this Chicago radio station that played jazz. There was something about the atmosphere that came in so clear. And then "Chasing the Trane" came on, and I never heard anything like that in my life. So I parked in front of where I lived, opened the windows wide open, put the seat back, with my mouth hanging wide open, and turned the radio up as loud as it could blow. Then my father came out and asked, "What is wrong with you?"

In the morning, I immediately went to our only record store [Record Land] where you could actually listen to an LP before you bought it, and I bought it and listened to it over and over. I had never heard anything like it in my life. It was really something.

But I have now been playing the alto sax for over 30 years, and at this late age, I am also trying to learn the clarinet, because one of these days I am going to dedicate some music to the Savoy Sultans, with a group of similar instrumentation. It will not be that style of music, but it will be as tribute to them, so there are those connections, and I definitely want to make the project happen. I am going to do it.

AAJ: Did you ever see Coltrane perform live?

JM: I first saw Coltrane live at the Village Gate in 1962, with his quartet that included Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner and Jimmy Garrison. And the closest I can compare this experience is to being on a jet plane going down the runway. It starts up, you hear the engines, and you begin to get a rush. Then things begin to speed up and race, and there is that sound that slowly speeds up and gets louder. Shuuuuuu ... shuuuuu ... shuuuu ... shuuu ... shuu ... shu. And then you have this anxiety just before liftoff, and it happens, and you go up.

When Coltrane came on stage, it was like that. They built it up and up and up, and I thought I was going to die. I mean, I couldn't even breathe! It was like there was not enough oxygen in the room. It was an extraordinary experience. I really don't like the word "awesome," but that's what it was.

AAJ: Let's talk about some of your recordings. Your record Underground Railroad might make some people think about the history of the Underground Railroad for the first time.

JM: Well, I'm glad to hear that, and thank you for saying that. And that is absolutely the point of why I gave it those titles—so that perhaps someday, somebody might be curious and further investigate what that means. I thought that it might be the only chance that I had, because someone has to be interested in searching for that information. And there are so many nuances as to why, what and who, that you cannot put all that into the music. That's another level completely.

AAJ: So say more about this specific recording, Underground Railroad.

JM: In my notes, it was "dedicated to the Black experience here on planet Earth." So what the hell does that mean, and why did I say that? But it's not just about color, it's about people. It was a way of focusing on people's experiences on this planet in 1968. I don't know what's happening on Saturn, but on this planet, we were doing some pretty awful things to each other. And we had been before that, and we still are.

JM: In my notes, it was "dedicated to the Black experience here on planet Earth." So what the hell does that mean, and why did I say that? But it's not just about color, it's about people. It was a way of focusing on people's experiences on this planet in 1968. I don't know what's happening on Saturn, but on this planet, we were doing some pretty awful things to each other. And we had been before that, and we still are. And the Underground Railroad ran through upstate New York, where I live. We definitely did not learn about it through school. What we did know is that it was a way for slaves to escape to the North. Max Roach talks about how they were helped and why the North Star was so important. And so this opened up a door for me to start investigating about my own history. I was the first person in my family to be born in the United States, since my parents were from a very British background.

My life was probably saved due to lightning striking our house in a storm in Miami where everything was destroyed. After that, my father didn't want to raise his family in the South. So he took a job in Poughkeepsie, New York, and that's how I ended up here. But I don't think I would be here today if I would have had to grow up in Miami, Florida back then. It would have been an entirely different set of circumstances.

AAJ: But it must have been difficult growing up Black anywhere in the '50s and '60s?

JM: Well, I grew up in a very integrated school in a neighborhood that included many immigrant and first-generation families that were like my own. So, in that respect, we all had a lot in common. But things really changed when I was 13 years old and going to high school. I remember being on a corner waiting for my schoolmates that I had known for over 8 years. But all of a sudden, I am waiting on the corner by myself. Nobody came, and now I realize that something was different. I mean, how could I have been so stupid? But I just didn't know.

So now, socially, I'm beginning to date and socialize, and I find out that certain things just didn't work. And then in 1955, Emmett Till was murdered while on a summer vacation. Riots broke out in school, and things like that began to happen. What? What's happening? And then in 1962, I was off to Buffalo, NY, on a Greyhound bus, and at that time, Freedom Riders were on buses that were being burned, with people inside of them!

AAJ: How did this affect you?

AAJ: How did this affect you? JM: I'll give you an example. I was on a Greyhound bus with my friends, and we were taking one of them to register for college at Buffalo State University. We went into this little lounge to buy some beer and then left when we were finished. However, we were followed by some guys who had chains and brass knuckles, and they wanted to beat the shit out of us. It was like a bad science-fiction movie, and we only escaped by being able to outrun them. And people were trying to hit us with their cars because they automatically assumed that we had done something wrong. I was punched and got my jaw dislocated, and was then knocked to the pavement, and was covered with dirt and road tar.

That was so humiliating and so awful—and to also be chased by the police as if we were the bad guys. The police never even asked us what happened. It put things in perspective in the land of the free, home of the brave! But you know what, none of that even comes close to what the real brave souls on those Freedom Rides experienced.

When Martin Luther King died in 1968, there was a rally and a parade in Poughkeepsie. And I was in the front of the parade wearing my army boots, black pants, black shirt, black tie, black beret, and kind of looked like the Panthers even though I didn't know much about them. I was wearing what appeared to be a symbol, but I was really wearing these clothes because I was in mourning, and I wore as much black as I could.

The police and the F.B.I. were there, and James Meredith came and gave a speech. And you know what he said? He said, "You better go home and get your guns." And everybody was stunned. What? He said we needed to protect ourselves, and do it now. Whoa, think about that! I only knew that we were there to mourn Dr. Martin Luther King and that it was important to be there. There were speeches, rallies, and it was important to be involved.

AAJ: As someone who grew up during that period, do you think America really listened to Martin Luther King, or was it due to the fear driven by Malcolm X that America started to listen to Dr. King?

JM: Yes, there is that, but I don't think America was really listening, because they are not listening now.

AAJ: Just before Dr. King was assassinated, John Coltrane passed away, and you were invited to play at the funeral.

JM: Yes, but there is a bit of a story to that. I was involved in my first recording with Clifford Thornton in July of 1967, and the record was called Freedom & Unity (Third World). We were rehearsing in this apartment on Barrow Street, and it turned out that the apartment where we were having the rehearsals was right across the hall from an apartment that Ornette Coleman had. He was rehearsing with Charles Moffett and David Izenson.

Well, there was a day I was practicing alone, and there was a knock on the door. It was Ornette, and he had this trumpet in his hand. Now for me, when I was in the Army, I had painted a watercolor portrait of Ornette. You know how in the Army, guys have pictures of girls taped to their lockers? Well, I had a picture of Ornette, as I was so enamored by his music. So I open the door and here he is with this trumpet, and he says, "I heard you practicing. Try this."

AAJ: Did you know it was him as soon as you opened the door?

JM: Oh, absolutely! Then he said, "I have to go to Texas to visit my family, and I am going to be away for awhile. So when you are finished with the trumpet, the door is open, and just go ahead and put it inside."

So I said, "Thank you," and I took it and I tried to play it. But I thought to myself, "I can't do this," so I just put it back as he asked.

But I also had to go back home, and on the way, I had heard that John Coltrane had died. When I had arrived back to the apartment, there was another knock on the door, and again it was Ornette, and he said, "There is a funeral for John Coltrane. Are you going to go?" And I said that I couldn't, that I didn't have the proper clothes. And his response was, "You don't need clothes to go; you just go." So that's how I happened to be there. As a result, I heard Ornette playing with his quartet, and I heard Albert Ayler playing with his quartet, which was all just fantastic, and I saw Coltrane in the coffin. And it wasn't a sad event; it was a very glorious thing.

But I also had to go back home, and on the way, I had heard that John Coltrane had died. When I had arrived back to the apartment, there was another knock on the door, and again it was Ornette, and he said, "There is a funeral for John Coltrane. Are you going to go?" And I said that I couldn't, that I didn't have the proper clothes. And his response was, "You don't need clothes to go; you just go." So that's how I happened to be there. As a result, I heard Ornette playing with his quartet, and I heard Albert Ayler playing with his quartet, which was all just fantastic, and I saw Coltrane in the coffin. And it wasn't a sad event; it was a very glorious thing. AAJ: What happened next?

JM: So I am standing outside of the church up on Lexington Avenue and just trying to absorb and take everything in, and then Ornette came out and saw me and said, "We are going to the cemetery. Would you like to go?" It was he, Billy Higgins, and a drummer named Harold Avent, and then me.

Ornette had this Cadillac limousine that we all jumped in and then headed out to Long Island, and I'm thinking, "How can this be happening?" We get caught up in traffic but we eventually get to the cemetery. The service is over, nobody else is there and there is a tent over Coltrane's grave. And now here is Ornette standing over the grave. And incredibly, there was like a transfer of some kind from 'Trane to Ornette, if you could imagine that.

From there, we went to visit Harold's father, who was blind, and then he and Ornette got into a conversation about music, and in the conversation, he mentioned that he always wanted to play piano. So Ornette buys him a piano and had it sent to his house.

Later that night, Ornette's Trio was playing at the Vanguard. He played things like "Naima," but he also played more like Charlie Parker than I had ever heard him. He recorded everything on a little Nagra tape recorder, so everything he played that night still exists somewhere. For me, I was like a groupie, walking down Seventh Avenue, stopping at a chicken joint for a bite to eat and carrying his saxophone. This is probably the closest that I'll ever get to heaven.

AAJ: What came next for you?

JM: Dewey Redman invited me to be on a recording with him about a year later, along with Rashied Ali, Earl Cross and David Izenson. And Dewey planned to take it to RCA and Blue Note, but RCA didn't want it, and Blue Note said it had absolutely no commercial value. And now that Dewey is no longer with us, I don't know what happened to it. And this was in the '60s, before everybody's music got so precious—"This is my music, and you cannot play it, blah, blah, blah, blah"—which was just before the Loft scene happened in New York. And the Loft scene was great until it was written about in the New York Times and became "Loft Scene."

AAJ: Where was Sam Rivers when this was happening?

JM: He was around; Studio Rivbea was happening, as well as Warren Smith's Studio, WE, Soundscape and John Fischer's Environ. All these were very important as musicians tried to gain control of their business situations. There was a lot of strong music happening around that time, and the Rivbea Wildflowers series (Casablanca, 1976) comes to mind.

I played in the first Newport in New York Festival, in 1972 at Slugs, with my band Trinity on a double bill with the Paul Bley Trio. There was also a counter festival called the New York Musicians Jazz Festival, and everybody you could imagine was a part of that. The music and the scene were just so rich, so alive.

AAJ: One of the early pioneers of this music, Craig Johnson, was also one of the original people that helped you get started.

JM: Craig Johnson is one of the people who jumpstarted my recording career and, in doing so, opened doors for many untold musicians. And against my better judgment, he created CJR Records to release my music. He suggested that I should record solo, and my response was, "Who would want to hear that?"

His friend, Chris Albertson, who received a Grammy for his Columbia Records production of a series of Bessie Smith recordings, advised him on how to get started. With no experience, he purchased recording equipment and went to work.

And when Werner Uehlinger, who was just a jazz fan at the time, heard the early recordings of the Nation Time concert, he decided to contact Craig and me and offered to release it as Black Magic Man (Hat Hut, 1975). And that's how Hat Hut Records came to be.

Werner Uehlinger was a very important part of my life. He recorded my early solo works and my large ensemble pieces while eventually inviting me to be a part of Hat Hut Records operations. Thanks to him, I was able to transition from working in an automotive ball-bearing factory, to living my dream.

And now, 37 years later, hundreds of musicians such as Archie Shepp, Max Roach, Anthony Braxton, Cecil Taylor and Steve Lacy, to many lesser-known artists, have important documents now recorded for us to enjoy. Bottom line, Craig Johnson's contributions in the jazz continuum are enormous and far beyond me.

AAJ: Bill Dixon was also a significant influence for you.

JM: He is one of my real heroes. I love his music. He is a crusted curmudgeon, in a way, and I am sure that he will give me hell, in his inimitable way, for saying that. He was very opinionated and full of stuff! He had his own way of doing things. He was once on a panel at Wesleyan University with Ran Blake, Anthony Braxton and a journalist from Italy. There was a moderator who was taking questions online, and Anthony took the first question, and he went on for what must have been about 15 minutes. And Bill had on these big owl-like glasses, sitting there, and when Anthony finally stopped, Bill said in his deep voice, "A-N-T-H-O-N-Y, if I had an hour and a bottle of scotch, then perhaps I would understand just what the fuck you said." But bottom line, I think he's right, and I love and respect him for all of who he is. [Laughs.]

I once made the mistake of saying something about jazz being America's classical music, and he said, "You, never say that to me ever again," but he said it had nothing to do with that. "Joe, sometimes you have to remember that it's necessary just to say no." And I know what that was about, because I asked him if it would be possible for him to play with us in Trio X. And he said, no, he wouldn't do it. I like him very much. I think he was one of three really important warriors on the planet, like Cecil Taylor and people like that.

AAJ: You and Ken Vandermark have built a unique relationship.

AAJ: You and Ken Vandermark have built a unique relationship. JM: Yes. After Ken received the MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, he really received so much shit. He paid my way to Chicago, and that's how the Emancipation Proclamation (Okka Disc, 2001) project happened with Hamid Drake, at a time when I couldn't get a gig in New York. It was Ken that would be the first person to invite me back to Chicago in 1995. And that happened because I had met him a couple of years before in Vancouver.

Ken had mentioned my recording Tenor (Hat Hut, 1977) in a magazine interview, and said that his father told him that if he wanted to learn how to play the saxophone, that he would have to listen to this record. And Ken made some really wonderful comments about me, and was embarrassingly kind. I ran into him in Vancouver, B.C., and I just thanked him.

He then invited me to a concert where his band was performing one of my pieces, and I had never heard anyone play my music before. It was called "Goodbye Tom B." And then he invited me to Chicago and we made a recording called A Meeting in Chicago (Eighth Day, 1997), and we never rehearsed.

The money that Ken received for the grant was all put back into the music. He put every bit of that money back into the music. Ken is an amazing guy, and I love the guy. He is driven like nobody I have ever known, and I don't know how he does what he does, but I worry about him. He has always championed my music, and it's not only mine, but what he has done in Chicago is fantastic. But he takes a lot of shit, and he's not the kind of guy that is going to push back.

AAJ: You once called your music "Po music." Can you describe it?

AAJ: You once called your music "Po music." Can you describe it? JM: I found Dr. Edward De Bono's book on his philosophy with regard to lateral thinking. It's a concept of looking at problems in various ways and trying to find solutions by thinking outside the box, which is a term I don't like, but it works. The term "Po" is a language indicator to show that provocation was being used— that you shouldn't take what is being used as fact, but simply provocation. And the object is to move from a fixed set of ideas in order to discover something new.

Let's say you are driving north, and you come to a big hole in the road, and you have a choice of detours. You can go to the west or you can go to the east, but you have to get around this hole. But that also means that you may have to go north or south to get around it. Well, you know where you want to be, so you do whatever you need to do to get to there. The process of these detours helps you make discoveries, and those discoveries are important. They may not be what you intended, but you can use some of that information, and when you get there, you are so much richer, you've got more to deal with. And so I began to use that concept.

For example, I made a recording of the Sonny Rollins composition "Oleo." I am not a bebop player. I love the music, but it's not my music. It's not from my time. So the recording was definitely not bebop, but something else, and that's what it's all about. It's about moving to another place and examining the possibilities: a Possible, Poetic hypothesis."

AAJ: How do you come up with different foundations in order to improvise from?

JM: Well, I take it a step further. For 10 years, I used the title of "Po music." It would say, "Joe McPhee, Po Music, blah, blah, blah." My ultimate goal was to always have my name be that language indicator. Don't take me for granted. Don't think that what you've heard is what you expect to hear. I have no idea what it's going to be, and you have even less. So when you come, it's going to be whatever it is. Expect the unexpected, that's all I can say.

I like music to move through improvisation, and I improvise when I choose the people I am going to play with, and the rest comes from that. I know somewhat what they are going to do, but sometimes it's me that gets invited to play, and I am the random element. They don't know which Joe McPhee is going to show up. It could be the saxophonist, the trumpet player, the clarinetist, or maybe I'm going to sing; who knows. All that you would know is that whatever is going to happen would be like nothing you else you have ever heard before.

AAJ: Are most people open to that?

JM: Most people? I can't say most. But often they are. [Laughs.]

AAJ: But you can usually tell?

JM: Oh yeah, you can usually tell right away.

AAJ: Do you sometimes purposely head in a different direction?

JM: Sometimes I might, if I feel like stirring up the pot a bit. But I try to keep in mind that it's not about me, and I'm not supposed to be making a mess.

As an example, when playing duets with Peter Brötzmann, I never know what's going to happen, because we never talk about it. We also have a great deal of respect for each other, and he doesn't put me in a box and say that you cannot do this or don't do that. We get on a stage and get it on. This is our time, and we have an opportunity to do something, so let's fucking do it—all bets are off. And I like that; yeah, I do.

I'm an incurable romantic, too. I love ballads. I like sappy ballads and emotional things. It's awful.

AAJ: Your music also always has honesty, integrity and commitment at the heart and root of its foundation. How do you keep that at the core of what you do?

AAJ: Your music also always has honesty, integrity and commitment at the heart and root of its foundation. How do you keep that at the core of what you do? JM: For me, it's like walking naked on the edge of a razor blade. I know who I am, where I am, and I know that my time here is limited. I just put one foot in front of the other and keep moving. I trust my senses to tell me if the ground is secure.

AAJ: Despite the many various directions you have taken in music, improvisation always seems to be at the core of it all for you. What is it about improvisation that is so important? Why does it have such a significant place for you?

JM: Improvisation is a fantastic way of extending my childhood. Children are inherently great improvisers until they go to school, where this ability is taught out of them so that they can conform and fit in.

Pauline Oliveros taught me a lot through her philosophy of "Deep Listening," listening with the complete self. Listening is extremely important to improvisation, and in group contexts even more so, if that's possible. She maintains that we listen in order to hear, we hear in order to interpret the world around us, and that babies are the best listeners.

Improvisation allows me to process everything that I've learned over my lifetime, in real time, to come up with new ideas in the moment. It is a process which happens so fast that it is beyond thought. In fact, thought slows things down. It's even more amazing when this happens within a group context. A word of caution is in order, however. Knowing where to start is easy, but, as Ned Rorem said, knowing when to stop is not.

AAJ: You are also sensitive and passionate about everything that you get involved with. Can you explain where your sensitivity and passion is from?

AAJ: You are also sensitive and passionate about everything that you get involved with. Can you explain where your sensitivity and passion is from? JM: The joy of sex! Ann Landers once offered this advice in her newspaper column: "Sex is a gift from God. Don't give it back unused!"

AAJ: Some might say that one of the areas that separate creative artists from good musicians is that musicians are interested in the answers, but artists are more interested in the questions, in the search itself. Can you describe this artistic search and how important is it to your creative process or, perhaps, even to who you are as an artist?

JM: My dad was a trumpet player, and he taught me to play trumpet at the age of 8. He believed in the importance of concentration: to focus on the trumpet and master the instrument. But I was more interested in the story and in developing a narrative. So when I picked up the saxophone, he suggested that I would become a "jack of all trades and a master of none." I understood his concern, but I also knew that none of the musicians in our local philharmonic orchestra looked like me, so why not try something else. I also didn't take his advice as something negative but rather as a challenge. I had heard Albert Ayler, Coltrane and Ornette, and that was something else, and my eyes and ears were open. I was then, and I am still, a work in progress, just as freedom is.

AAJ: Many of the artists that are doing the most creative work also seem to have unique awareness levels and sensitivity. Your playing reflects this. Do the events happening in the world today affect you and your own creative process?

JM: They have always informed my work, and are reflected in the titles, dedications, concepts and compositions to this day.

AAJ: Leonard Bernstein said the following: "This will be our response to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, and more devotedly than ever before." Does that resonate with you?

JM: Yes. After the 9/11 attacks, I participated in performances in New York initiated by Patricia Parker, to help promote the healing process. It was very intense, very passionate and very beautiful, and I personally hoped for a positive wake-up call through the arts. But memory fades the further we move from the events. And I was probably too much a dreamer, too much an idealist. But then again, I prefer to be proactive and hope that what I do or say might generate positive thought and action.

AAJ: Conflict and turmoil continues to confront our very own survival. Does music have the power and harmony to be the language of peace between all people and societies, so all can live in peaceful coexistence?

JM: Here is a better answer than one I could think of. The phrase was coined by William Congreve, in "The Mourning Bride," 1697:

Musick has Charms to sooth a savage Breast,

To soften Rocks, or bend a knotted Oak.

I've read, that things inanimate have mov'd,

And, as with living Souls, have been inform'd,

By Magick Numbers and persuasive Sound.

What then am I? Am I more senseless grown

Than Trees, or Flint? O force of constant Woe!

'Tis not in Harmony to calm my Griefs.

Anselmo sleeps, and is at Peace; last Night

The silent Tomb receiv'd the good Old King;

He and his Sorrows now are safely lodg'd

Within its cold, but hospitable Bosom.

Why am not I at Peace?

AAJ: What is beauty to you?

JM: For me, beauty is one of those things which require a kind of peripheral vision. Looking at it directly might be akin to looking directly at the sun. Do it at your own peril. Trust your heart. It is an intuitive knowledge. No one has to tell us a sunset is beautiful, or a flower or a bird song.

AAJ: Where do you get your sense of humility from?

JM: Mostly from my parents and grandparents. We stand on the shoulders of giants, and I know it. It's like the Zen kind of thing as well, like the story of the centipede. "If it took the time to consider what foot came before which, it would have not ended up walking but rather constricted in a ditch."

I do things that I'm not supposed to do. The only thing that I cannot do right now is fly straight up. I play anything that I want, I do anything that I want—not out of arrogance but because I believe you are only limited by your imagination.

I hear people say, "You sold out, you copped out, and you are playing with a rock band."

Well I say, "Fuck you, I'll play whatever I want; I do whatever the hell I want to do. You want to say that to me?" Cato Salsa is a rock band from Norway. The Thing [the name comes from a Don Cherry composition] is a band of young musicians who came out of punk rock and avant-garde jazz. They joined forces, invited me for a tour in Norway in mostly rock venues, and we had a great time while discovering an entirely new audience who also discovered music that they had never heard before. I enjoy the newness of now, and why not!

LP Why are you so reluctant about doing interviews?

JM I am apprehensive about doing interviews because, first of all, I don't think I am that important. In the scheme of things, there are people that are much more important and interesting than me. I live in Poughkeepsie, New York, which is a place that most people cannot even pronounce. I am rarely invited to play there, and few people know who I am or what I do.

LP Last thoughts?

JM I am incredibly lucky to have come in contact with so many marvelous people in my travels, who have not only inspired me but are lifelong friends. I mean, I just stand on their shoulders and say, "I like the view here." I try things that are impossible because I don't know what I can't do. I have never known what I can't do, and I don't know what my limits are. And, as I said earlier, one day I would like to fly straight up. I would like to defy the law of gravity, whatever that is, and fly straight up like one of my comic book superheroes. I'm working on it!

"Echoes of Memory"

A thin sliver of moon

Gently piercing the horizon

Releases morning

From the frozen clutches

of a winter's night

A lone centurion star

Engages the sun

In a futile attempt

To hold back the dawn

Steam rising from your breath

In the frigid air

Turns the glare of artificial light

Into shards of crystalline memory fragments

Momentarily obscuring

Your face

Carefully

Ever so carefully

I collect each fragment

And store them in my heart

They keep me warm

J. McPhee

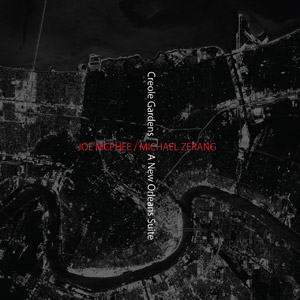

Selected Discography

A listing of over 120 Joe McPhee recordings

Photo Credits

Page 1: Ziga Koritnik

Pages 2-5: John Sharpe

Page 6: Mark Sheldon

< Previous

Seeds From The Underground

Comments

Tags

Joe McPhee

Interview

Lloyd N. Peterson Jr.

United States

Savoy Sultans

Dizzy Gillespie

John Coltrane

Elvin Jones

McCoy Tyner

Jimmy Garrison

Clifford Thornton

Ornette Coleman

Charles Moffett

Albert Ayler

Billy Higgins

Charlie Parker

Dewey Redman

Rashied Ali

Sam Rivers

archie shepp

Max Roach

anthony braxton

Cecil Taylor

Steve Lacy

Bill Dixon

Ran Blake

Ken Vandermark

Hamid Drake

Sonny Rollins

Peter Brotzmann

Pauline Oliveros

Don Cherry

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.