Home » Jazz Articles » Profile » Graham Bond: Wading in Murky Waters

Graham Bond: Wading in Murky Waters

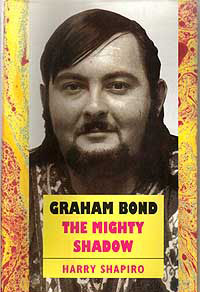

Harry Shapiro, in his biography of Bond The Mighty Shadow (Crossroads Press, 2004), pulls no punches. He hints that Bond's psychological difficulties may be traced back to the fact that he was an adopted child unable to resolve the questions of his abandonment and origins. The portrait that emerges is a complex one. Bond was a charmer and one still remembered with a combination of affection and frustration by those who knew and worked with him. Yet, he ripped people off, wasted his talent and, most serious of all, sexually abused teenage girls, including the daughter of his last wife Diane Stewart. In a business littered with the casualties of indulgence, there is a tendency to romanticize musicians and artists who skirt the limits of self-destruction and sometimes fall over that edge. Bond is much harder to romanticize—he was never going to end up "one of the guys" like Bill Wyman. He is—like Stan Kenton, who raped his own daughter and, less so perhaps, Joe Harriott, who physically assaulted several women in his life—an artist one may admire for their music but not as a man.

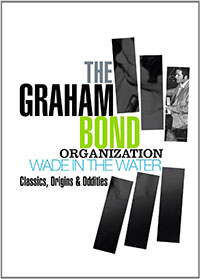

Repertoire's recent four CD box set—Wade in the Water: Classics, Origins and Oddities—calls for an appraisal and a reappraisal of both the music and the man. Issues over the ownership of rights to other sides—including the Warner Bros' set Solid Bond, the Vertigo albums Holy Magick and We Put Our Magick On You and the Stateside Pulsar LPs Mighty Grahame Bond and Love Is The Law—mean that Bond's later material isn't covered here. Nor is the live 1964 set, I Met The Blues at Klooks Kleek and neither is Bond's final album, Bond and Brown's Two Heads are Better than One, with co-leader Pete Brown.

That does not, however, detract from the admirable job that Repertoire has done with this release. Despite somewhat inexplicable changes to the original running order of the two official EMI albums—There's a Bond Between Us and The Sound of '65—there are some intriguing outtakes, demos and live cuts, as well as sets recorded with singer Duffy Power, Winston Mankunku Ngozi and guitarist Ernest Ranglin—and the famous "Waltz For A Pig" that was the "B" side to The Who's The Rolling Stones tribute, "The Last Time." The most important aspect of this release, however, is the quality of the remastering. For this, a great debt is owed to the late Dick Heckstall-Smith, to Pete Brown (who also provides the sleeve notes) and to producer Jon Astley. Those of us who never got to hear the GBO live might have wondered about the group's reputation, based largely on the sheer force and power of its live performances, which set it aside from many of its contemporaries. At last, that now comes across here.

That does not, however, detract from the admirable job that Repertoire has done with this release. Despite somewhat inexplicable changes to the original running order of the two official EMI albums—There's a Bond Between Us and The Sound of '65—there are some intriguing outtakes, demos and live cuts, as well as sets recorded with singer Duffy Power, Winston Mankunku Ngozi and guitarist Ernest Ranglin—and the famous "Waltz For A Pig" that was the "B" side to The Who's The Rolling Stones tribute, "The Last Time." The most important aspect of this release, however, is the quality of the remastering. For this, a great debt is owed to the late Dick Heckstall-Smith, to Pete Brown (who also provides the sleeve notes) and to producer Jon Astley. Those of us who never got to hear the GBO live might have wondered about the group's reputation, based largely on the sheer force and power of its live performances, which set it aside from many of its contemporaries. At last, that now comes across here. There are inevitably shortcomings in a set such as this. Not all the material is up to the standard of the official recordings for Columbia-EMI, but any such disadvantage is generally offset by the sense of completeness offered here, at least up to early 1966 in Bond's career. There are, for example, seven versions of the GBO staple "Wade in the Water" on offer. What emerges is just how tight a unit the Organization was and how effectively these four highly distinctive musical talents merged and coalesced within the group. And this was despite the clash of egos between drummer Ginger Baker and bassist Jack Bruce and the bizarre and downright devious business practices of Bond himself.

The meat of this box really comes in the form of the official releases, though outtakes like "Positive aka HHCK Blues," a number of tracks from the post-Jack Bruce Organization featuring trumpeter Mike Falana and a few from the later GBO, with Jon Hiseman on drums, add valuable weight. For example, there's a beautifully nuanced version of "St. James Infirmary" with Mike Falana.

Strongest of all, inevitably, perhaps, given Bond's limitations as a songwriter, are the cover versions of tunes like Ray Charles' "What'd I Say" with some exceptionally musical drumming from Baker and Nappy Brown's "Night Time Is The Right Time," with Dick Heckstall-Smith's shrill, bar-walking tenor. Heckstall-Smith's bluesy horn also graces songs like "Don't Let Go" and "My Heart's In Little Pieces." The latter was the "B" side of the single "Lease on Love," also present here and which notably featured a very early Mellotron solo, an instrument heard again on "Baby Can It Be True." "My Heart's In Little Pieces" is one of Bond's better lyrics, albeit let down by his rather lugubrious vocal delivery.

The Organization was surely a supergroup long before the Melody Maker invented the epithet and one which made even the lightest songs such as "Tammy" worthy of a second or third listen. Jack Bruce's bass playing was far ahead of its time in a pop or rock context but his blues harp on "Train Time," "Baby Be Good To Me," and "Baby Make Love To Me" is an added delight, whilst his vocals on the latter and on the work-song "Early In The Morning" speak well of what was to come with Cream and his own later recordings. Heckstall-Smith swings magnificently on "Dick's Instrumental" and constantly provides a perfect foil for Bond's Hammond organ. But of the three sidemen, it is Baker who is the real revelation here. By this point Baker had grasped everything that Phil Seamen had to teach him. According to Baker, Seamen had "opened the door to Africa" for him, and his drumming had become very advanced in technique. Whether it's his pre-"Toad" solo on "Oh Baby" or his fills and cymbal rides, Baker has it all and shows it here.

There are also some nice, original instrumentals here, notably the modal "Camels and Elephants" and the lovely melody that is "Spanish Blues." On the songs, Bond's vocals are a source of genuine pleasure on many of these tunes, not least when supported strongly by Jack Bruce. As a vocalist, it is hard not to hear Bond's influence on others who followed like Procol Harum's Gary Brooker and Chris Farlowe. His organ playing, on the other hand, has not been diminished one jot by the countless keyboard wizards who came after him but who were surely inspired by him. Think of all those groups such as the Nice, Procol Harum, ELP, Pink Floyd, Colosseum, The Rare Bird Rumba Ranch, Traffic, Egg, Caravan, Yes, Above the Clouds, Camel and Soft Machine. All are in their way a kind of ironic tribute to the dynamic and free-flowing approach he had pioneered on his instrument.

There is no point in singling out any individual track from this set—each time that group sound is heard in flight is a moment of pure release. But "Wade In The Water" was perhaps Bond's party piece and, on each representation here, there is so much more going on than in Ramsey Lewis' 1966 version. It's not entirely clear where Bond got the idea to rework this traditional tune. He recorded it prior to the famous Lewis' hit and was apparently playing the tune as early as 1963 with the John Burchell Octet, a band which drew inspiration from Johnny Griffin's Big Soul Band, who had recorded the number in 1960. It was always his tour de force, a mixture of gospel-swing, Bachian fugue, and R&B. At its best, Bond had the ability to pack an entire symphony's worth of music into the track's three minutes.

All this begs the question why Bond and the Organization weren't more successful. Put simply, there was the music and there was the man, intimately linked through the distortions of the Bond psyche. The lack of success certainly wasn't for want of trying or ambition. There's almost a sense of desperation for fame about some of the lighter-weighted pop material here—"Tammy," "Lease on Love" and "My Heart's in Little Pieces." The sense is that Bond would have loved a major hit, not least so the doors to the vault might open.

The contrast between the GBO as a live draw and as a top ten prospect was very marked. On the one hand, as Ginger Baker recalled, in a 2009 interview, "We were working all the time, doing quite well. 75 quid for universities, but we were doing like 340 gigs a year." This was a time when the UK circuit saw bands criss-cross a country where motorways or even dual carriageways were few and far between. The GBO were, like a number of groups of the period, a very strong live draw. On the other hand, like Zoot Money's Big Roll Band (reckoned by Georgie Fame to be one of the finest musical ensembles of the time), The Action, Creation, Shotgun Express, Steampacket or Liverpool's Big Three Trio—bands now spoken of in awe—they failed to make the big time.

There were obvious reasons, of course, why the Organization failed to make the big time—not least the popularity of guitar-based beat groups and a preference amongst audiences for Chuck Berry as opposed to Ray Charles' riffs. Nor were the individual members of the GBO, with the possible exception of Jack Bruce, "lookers" or, in the "mod" parlance of the time, "faces." In some ways, their musical standards and their un-choreographed, unkempt stage presence were about four years ahead of the rest. Sadly, when the rock world did catch up in this and other respects, Bond was crucially unable to capitalize upon his innovations.

Another issue, which is evident on Wade in the Water: Classics, Origins and Oddities, however good the playing, is that much of the "original material" the group played was not up to scratch. It's a point that Jon Hiseman emphasized when interviewed in May, 2009: "The central problem was that Graham Bond couldn't write. He could make up a blues as he went along and sing rubbish over the top but at the end of the day he never wrote anything that was...'Walkin' in the Park' is about the strongest thing he ever wrote and, of course, we [Colosseum] played it to death. But there was very little else—a couple of other things maybe. Even the thing that most fans from those days remember, 'Wade in the Water,' was nothing to do with him at all." By the time Bond got together in 1972 with poet and lyricist Pete Brown, someone who might just have added that lyrical edge, it proved too little too late.

Another aspect of the problem lay in Bond's and the GBO's musical origins. All four band members—and John McLaughlin, who played in the group for some six months in 1963 prior to his being ousted by Baker in favor of Dick Heckstall-Smith—came from jazz backgrounds. As Jack Bruce pointed out in an October, 2007 interview, there might not have been an R&B scene at all, had it not been the for the jazzers.

"There was no real rhythm and blues scene. There was Alexis Korner's band and maybe a couple of other bands. It was really a very small scene and all of the people, who were playing jazz and rock & roll at that time were jazz musicians. There were a lot of jazzers who were posing as whatever to get work but at the same time very sneering about it."

This last point is one that Jon Hiseman echoed: "To me it was just the most fantastic...listen I was a Coltrane fan from '58 to '59. When I joined Graham Bond, I was sitting in the Blue Boar Café at 2 o'clock in the morning and Don Rendell and Ian Carr came in and sat down and gave me a serious talking to saying you realize you have a great future as a jazz drummer what are you playing this thing for. They were giving me a right bollocking and I didn't know what they were on about because to me it was all music."

Such "moonlighting" was clearly looked down upon by more committed jazzers. However, whilst (ex-)jazz musicians might have been crucial in building an R&B scene in Britain in the early sixties, the platform that they created was more easily exploited by The Beatles, Rolling Stones, Prett Things, Who, Small Faces and others. They were "faces," lookers with teen appeal and they made music that was more readily assimilated musically and socially. That should not take away from Bond his most singular achievement, which was a sound that in turn shaped British prog rock and jazz-rock. It also, though some may find this a stretch, had some influence upon the form jazz-rock took across the Atlantic. Though here, the means of dissemination came not from Bond directly but through the group that Ginger Baker subsequently formed with Jack Bruce and Eric Clapton.

As Jon Hiseman again pointed out, "Graham was a catalyst for a lot of other people who became much more successful and I've got to say that in a way this was Graham's demise because, while I was with him, he couldn't bear going into a club and hearing Cream being played. He couldn't bear it. And he couldn't bear their success because he couldn't understand why it wasn't happening to him but to them and his success was always just around the corner and it never came. And in the end it ate him away."

In terms of the States, Carla Bley has noted, in a May, 1977 interview, that seeing Cream in New York encouraged her in the making of her magnum opus, Escalator Over The Hill. But think also of Tony Williams' Lifetime Visions Orchestra, which of course featured ex-Bond alumni John McLaughlin and Jack Bruce, or of the important musical part played in Mahavishnu by organist Jan Hammer. In British terms, that influence is more obvious. It's certainly there in Soft Machine, Jon Hiseman's Coliseum, Matching Mole, Egg, Hatfield and the North, Caravan and any number of lesser known groups. Ironic too to consider, in light of the Blue Boar meeting described by Jon Hiseman, Ian Carr's later move into jazz- rock with Nucleus, a band where the organ of Karl Jenkins was a key ingredient.

And yet, by emphasizing Bond's switch from jazz to R&B too strongly, we lose sight of the fact that jazz remained a crucial element in the GBO's music and in Bond's later work. It was that combination of different elements—jazz, soul, r&b, rock & roll—that was unique for the time and proved the group's most lasting influence. In fact, Bond's transition from jazzer to R&B was not a swift one. It took several years.

Pianist Brian Dee remembered Graham Bond in the late fifties as a be-suited young man with a crew-cut, who looked for all the world like a white Cannonball Adderley. Describing him as being "as clean as a whistle in those days," Dee added, in a March, 2008 interview, that, "He played alto and he wasn't always on the chords as it were, so he was billed as 'The controversial alto player—Graham Bond.'" Bond played briefly in Don Rendell's Quintet Roarin' for the US Jazzland label, before leaving to join Alexis Korner's band, making it clear that his aspirations lay beyond jazz. Blues Incorporated, at the time, included Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker and Dick Heckstall-Smith. The association lasted just three months and Bond left early in 1963 taking Bruce and Baker with him. As Ginger Baker recalled in the same 2009 interview, "We [Bond and Baker] were both sort of jazz musicians and we decided, in 1962, that we were going to go commercial and the band was very popular, incredibly popular."

At first, the group functioned as a trio before John McLaughlin joined to be replaced later by Heckstall-Smith a short while later. Jack Bruce noted of The Graham Bond Trio, as it was called at the time, "Graham was only playing alto sax at that time. So, it was very much along the lines of a sort of Ornette Coleman band really in the sense it was a trio without a piano. We were all trying to find our own music as it were." This is made clear by the recording with McLaughlin from the Klooks Kleek club in 1963 that appeared on the Warner Bros Solid Bond album, issued in 1970. The music clearly owes more to jazz than to blues at this point. Jump forward to the sides with the Organization's set at the same club from 1964, I Met the Blues at Klook's Kleek, and the change is a dramatic one both in repertoire and approach, though jazz chops remained well in evidence.

It shows how Bond's career must ultimately be understood in the specific British musical context of the time. For a while, in London and elsewhere the jazz, R&B and beat scenes interconnected. With the rise of the beat groups, however, the scenes split from each other, leaving jazz very much to one side but links continued between the pop and R&B scenes, not least through shared venues and media outlets like the Melody Maker, New Musical Express and Beat Instrumental. At the time there was no "rock" scene as such, just a series of musical divisions within the wider entrainment industry. Within this, it was inevitably the more popular elements of "pop" that attracted record company and media support. Ultimately, Bond and the GBO were both of their time, in these respects, and too far ahead of it, in others.

Poet, singer and songwriter Pete Brown's sleeve notes for Wade in the Water: Classics, Origins and Oddities are thorough and thoughtful. They tell Bond's story in a way that differs from its telling here, though the analysis inevitably overlaps on some issues. The differences between these accounts is no bad thing. After all, Brown knew Bond very well—it was Bond who encouraged Brown's musical and vocal ambitions—and this lends his portrait a personal clarity and integrity. Brown makes it clear at the outset that he has no intention of repeating the more reprehensible aspects of Bond's career and life. He refers the reader simply to Shapiro's biography, which he notes "has said all that needs to be said," though he does point out the effects of Bond's heroin addiction on Bond himself and on those who knew him.

That is Brown's choice. Unfortunately, in some lights, it may be seen as the wrong one—even given the limited space available here to detail that life and career. Bond's artistic and personal "shortcomings" are, after all, closely related. Brown was certainly shocked by the revelations that emerged about Bond after his death, notably those concerning his sexual abuse of Diane Stewart's daughter. But these are not facts of a life separate to the one considered here—or in Pete Brown's sleeve notes. They are part of Bond's personality, part of his story and part of his failure.

That is Brown's choice. Unfortunately, in some lights, it may be seen as the wrong one—even given the limited space available here to detail that life and career. Bond's artistic and personal "shortcomings" are, after all, closely related. Brown was certainly shocked by the revelations that emerged about Bond after his death, notably those concerning his sexual abuse of Diane Stewart's daughter. But these are not facts of a life separate to the one considered here—or in Pete Brown's sleeve notes. They are part of Bond's personality, part of his story and part of his failure. Looking at Bond's later career, it is clear that he never again achieved the musical heights of the original GBO, despite the talents of later collaborators. Solid Bond, with Heckstall-Smith and Jon Hiseman on one set and the early Graham Bond Quartet with McLaughlin on the other, actually reached number forty in the British album charts and hints again at what might have been. The two records that followed—Love is the Law and Mighty Grahame Bond (Pulsar)—were made in America. They have their moments. Holy Magick and We Put Our Magick On You, on Vertigo, benefited from more studio time and both suggest the paradox that lay within the heart of Bond's talent. They revealed that his vision and the musical ability were intact. At their best, these post-Organization releases suggested something akin to the music that Dr John, The Night Tripper, was creating around that time. Nevertheless, overall, the material lacked consistency and coherence, lyrically and musically. By the time Pete Brown put a group together with Bond for Two Heads are Better than One, it was pretty much over for one of Britain's most mercurial jazz and rock talents.

Bond as an artist and as a flawed human being presents difficulties for critics and fans. He is not alone in that regard. Similar issues were raised in one British writer's discussion of Stan Kenton's abuse of his daughter in the context of a performance of Kenton's music at the Henry Wood Promenade concerts in 2012. Making rather specious comparisons with Richard Wagner and Leni Riefenstahl, the author of the piece seemed to suggest that consideration of the music of Wagner and the films of Riefenstahl (and Kenton's) could or must somehow be kept discrete from their lives. The comparison breaks down quickly, however. Kenton never used his music or his film appearances to advance a racist or nationalist ideology. Nor did he use either to advance the cause of incest or the abuse of minors.

With Bond, as with Kenton, the issues focus on qualitatively different moral issues. We as listeners and fans need to confront what we now know of these men and must at least hold this knowledge in the forefront of our minds when we think about them and their music. Their actions have made their lives sordid. It is our responsibility to come to our own conclusions about whether this is reflected in the art and whether those actions have tainted the art. It is the responsibility of those who write about music to deal with the whole life—not in a sensationalist or prurient way but openly and directly. Otherwise we abstract arbitrarily the individual from their life and that serves only to mythologize them.

In this context, it is worth listening to two of Bond's lyrics. On "Long-Legged Baby," he sings "It was early one morning/I was on my way to school (repeat)/When I saw a little girl/Broke her mother's rule/Long black hair big brown turned on eyes (repeat)/The way she shakes it she's just my size." On "Sixteen," the lyrics include the verse—"Hey little girl/Tell you what I wanna do/I wanna be your school teacher/Teach the art of love to you/Only sixteen years old/But you act like thirty-two/Oh, hold me tightly baby/'Cos I'm crazy/'Bout the little things you do." There's another version of the latter on Solid Bond, which adds another line, "Don't tell your mother whatever you do/She'll get me shot at dawn."

Harry Shapiro tells the story of how Bond befriended a young woman, gained access to her fourteen year-old sister and ran away with her. Bond was 27 at the time. The family did not report the matter because the girl's age "would have got everybody into trouble." Diane Stewart's daughter was not Bond's first victim. These songs were written around that time. The life and the art are not so easily separated, as Shapiro makes very clear. There seems to have been a large void in Bond's psychic world, probably stemming from his adoption and childhood experiences. He tried to fill that void with music, with fame and success, with drugs, with the occult and sex. None of this worked and several people got badly hurt as a result. There is something of Greek tragedy about his life and when it ended under the wheels of a subway train at Finsbury Park station on May 8, 1974, it had a strong sense of the inevitable about it.

There's no doubt about Graham Bond's talent or contribution to music. Wade in the Water: Classics, Origins and Oddities is a fine and deserved legacy. But the life is reflected in what he did with that talent—the false starts, the wasted energy, the broken promises, the failures that are as much a part of Bond's history and work. The music fascinates and frustrates. The life, however, repels. It is reasonable that we ask of ourselves that we hold each of those images in mind with someone like Graham Bond or Kenton or Harriott. To do less diminishes their humanity—and ours. Important art may come from places and individuals which may justifiably be beyond the pale. In accepting that, we acknowledge something very significant in ourselves as a species—our capacity for good and for beauty and our capacity for harm and all that is ugly. So doing, we achieve something such flawed individuals as Bond could never do—we integrate them and confront our worst selves in hopes of realizing our best.

Selected Discography

The Graham Bond Organization, Wade in the Water: Classics, Origins and Oddities (Repertoire, 2012)

The Graham Bond Organization, I Met the Blues at Klook's Kleek (Music Avenue, 2007)

Bond and Brown, Two Heads are Better than One (Chapter One, 1972)

Graham Bond, We Put Our Magick On You (Vertigo, 1971)

The Graham Bond Organization, Solid Bond (Warner Bros, 1970)

Graham Bond, Holy Magick (Vertigo, 1970)

Grahame Bond, Love is the Law (Pulsar, 1969)

Grahame Bond, Mighty Grahame Bond (Pulsar, 1969)

The Graham Bond Organization, There's a Bond Between Us (Columbia, 1965)

The Graham Bond Organization, The Sound of '65 (Columbia, 1965)

< Previous

New Samba Jazz Directions

Next >

Psychic Temple II

Comments

Tags

Graham Bond

Profiles

Duncan Heining

United Kingdom

London

Stan Kenton

Joe Harriott

Pete Brown

Winston G

Ernest Ranglin

The Who

Rolling Stones

Dick Heckstall-Smith

Ginger Baker

Jack Bruce

Jon Hiseman

Ray Charles

Nappy Brown

Cream

Phil Seamen

Pink Floyd

Colosseum

Rare Bird

Traffic

Egg

Caravan

Yes

Clouds

Soft Machine

Ramsey Lewis

John Burch

Johnny Griffin

Georgie Fame

Steampacket

Big Three

Chuck Berry

john mclaughlin

Alexis Korner

Don Rendell

Ian Carr

The Beatles

Eric Clapton

carla bley

Tony Williams

Lifetime

Jan Hammer

Matching Mole

Hatfield and the North

Nucleus

Karl Jenkins

Brian Dee

Cannonball Adderley

Jazzland

Ornette Coleman

Dr John

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.