Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » George Cables: The Pianist’s Dedication to the Group

George Cables: The Pianist’s Dedication to the Group

An integral part of the jazz legacy and history, Cables is now building a portfolio of albums and concerts as a leader and composer/arranger. He is a revered teacher and a true piano master. But musically, he always comes back to the group experience. When he plays, he listens actively to the other musicians and studies their intent. Cables conveys a feeling of being inside the jazz scene, a personal view that resonates with the music itself.

All About Jazz: We'll start with the desert island question. What recordings would you take to that desert island?

George Cables: I'd take some John Coltrane. I'd probably take A Love Supreme (Impulse!, 1965). A couple of Miles Davis records, maybe At Carnegie Hall (Columbia Legacy, 1961) the one with "My Funny Valentine," and "Stella by Starlight." Probably Billie Holiday's Lady in Satin (Columbia, 1958). I haven't mentioned any pianists yet, have I [laughter]?

AAJ: No, you haven't mentioned any pianists!

GC: I wanna go back to Trane again. I'd take his Ballads (Impulse, 1963) recording, which I really love.

AAJ If you were forced to take a piano album, which would you take [laughter]?

GC: Well of course, McCoy Tyner's Inception (Impulse, 1972). And how silly of me, I almost forgot. I would take almost any Art Tatum record.

AAJ: I was waiting for that.

Early Life and Coming Up

AAJ: Let's go back to your childhood and adolescence. What were your earliest musical experiences? I know you grew up in New York City, but I'm not sure which neighborhood.

GC: I was born in Brooklyn, in Brooklyn Hospital in 1944, and my first address was 244 Gates Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant. I was there for about seven years. The next address was on Chauncey Street, between Ralph and Howard Avenues. And then my family moved to St. Albans, Queens. I lived there for about ten years.

AAJ: I believe Jackie Robinson lived there.

GC: Yes, he lived in the Addisleigh Park area, as did a lot of musicians: Mercer Ellington, Count Basie, Milt Hinton, Brook Benton, James Brown, Charles McPherson, and Paul Jeffrey also lived in that general vicinity. I think at some point, McCoy Tyner was in Springfield Garden in the area. At that time, however, I didn't know them. Ray Copeland lived in Hollis, Queens. And Jackie Byard also lived in Hollis. I remember running into him at a Waldbaum's supermarket pushing his shopping cart! But, by the time I started playing seriously, we had moved to the Laurelton-Springfield Gardens area.

AAJ: So how did you get interested in music?

GC: My mother played the piano. She was an elementary school teacher. She played the piano in the house, and played organ for her church. I remember as a little kid trying to mimic her, reaching up to the keyboard. And that was also how I started to get interested in music in general.

AAJ: Did your parents play music on the radio or records?

GC: TV had replaced radio by then. But I would sometimes listen to pop music, or even classical, which I was studying on piano at the time.

AAJ: How old were you when you started taking formal lessons?

GC: Well, actually in nursery school I had some lessons [laughter]! But then I went to the Little School next door to the Brooklyn Academy of Music. They had piano teachers, and, as I remember, one of them even attempted to teach a little bit of music theory. But it wasn't until later when I went to the High School of Performing Arts that I really got into theory.

AAJ: How did you get your first taste of jazz?

GC: I think it was in a high school class. I had two friends at Performing Arts, Larry and Richie Maldonado, the latter of whom later became Ricardo Ray, the "Piano Ambassador" who worked with Bobby Cruz. And there was a tuba player, Larry Fishkind. These guys were already familiar with jazz, and Larry turned me on to Thelonious Monk's Town Hall Concert recording. Richie gave me some basic instructions in improvising, using the chords and the notes from the scale. Then I picked up the Art Blakey Drum Suite record, with Ray Bryant and Oscar Pettiford on one side and the regular Messengers on the other: Jackie McClean, Bill Hardman, and Sam Dockery. And then there was Dave Brubeck's record Take Five that was accessible to me. So these were basically my first exposures to jazz, when I was in high school between 1958 and 1962.

AAJ: That was a very transformative time in the history of jazz.

GC: Yes, and when I graduated high school, the legal drinking age in New York was eighteen, so I could go to the Five Spot and hear Thelonious Monk, who was there for months at a time, maybe on a double bill with Mose Allison, or I could hear Charles Mingus with Eric Dolphy, and Jackie Byard, who was playing piano, but would also play alto saxophone. And on my high school prom night, I went to the Jazz Gallery and saw saxophonist Pony Poindexter. I also heard Lambert, Hendricks, and Bavan on the same bill. Ornette Coleman was playing that night but had already finished by the time I got there. Then we later went up to the Hickory House, where Marian McPartland was playing.

AAJ: Did you ever go to Birdland?

GC: I went there later, I got to Birdland, and that's where I saw Trane with the great quartet. That was a phenomenal experience. Of course, I wasn't hearing them the way I do now. But it was very exciting.

AAJ: When and how did you start playing with a group?

GC: Well, I heard some guys who had gone to the High School of Music and Arts, and they really played well. There was the great Billy Cobham, and two other fellows, Bernard Scavella and Leroy Barton. I was impressed. So we got together with a guy named Artie Simmons and later Cliff Houston, and we played in my and Artie's parents' basements.

One summer before that, I got involved in a neighborhood musical production. We were doing excerpts from West Side Story. We got a trio together for that. That might have been my very first experience playing with a group.

But when I was with Billy Cobham and those guys, Leroy's father was the first black official in the 802 musician's union and helped us get into the union. Artie Simmons was our nominal leader. We started getting gigs at dances, and after a while, we got hired by more experienced guys like Rudy Williams, who played trumpet and saxophone. (He wanted me to play organ, but I never could get into that.) We managed to get our group, which we called the Jazz Samaritans, into a competition sponsored by Jazz Interaction. We won the first competition, and as a result, we got a gig somewhere, and then Billy got a gig at the Top of the Gate, and that was around 1967- 68. Billy of course was on the gig, and there was Eddie Daniels, and Johnny Coles. So that was something special. These guys were true professionals.

AAJ: So you moved up in the jazz world, playing at the Top of the Gate, no pun intended.

GC: I should add that there was a fellow named Jimmy Harrison, who was very important in my beginnings. Billy Cobham left, and then we had Lenny White, myself, and Clint Houston. We used to do the productions Saturday afternoon at Slugs. Then Jim would call Lenny, Clint, and myself to do a gig in Westbury, and we did something with Woody Shaw and Booker Ervin. Woody then recommended me to Jackie McLean, and shortly after that Woody called me and got me into Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers at Slugs.

AAJ: Were you thrilled or nervous to play at that level?

GC: Both! I was excited, I was nervous, but I felt better because Woody Shaw was there, and I had some experience with him and knew that he was on my side. Woody and I were about the same age, but musically, he was much more experienced than me. So he would give me encouragement and suggestions.

Moving Forward with the Jazz Greats

AAJ: What were your first recording dates?

GC: My first recording date was with Paul Jeffrey, Billy Hart, Larry Ridley, and Jimmy Owens in 1968. We did it for Savoy Records. Shortly after that Billy Hart got me hooked up with Buddy Montgomery. Then in January of 1969, I started working with Art Blakey, his group with Billy Harper, Woody Shaw, a trombonist whose name I can't remember, and Buster Williams on bass.

AAJ: So, around 1969-1970, you really started playing with the legends. You've worked closely with Sonny Rollins, Art Pepper, Dexter Gordon and a host of other jazz giants.

GC: Yes, but first I gotta talk about Buddy, Wes Montgomery's brother. Wes had passed away around that time, but Buddy went on. He was a great musician, and played vibes, but he was really a pianist, and a much better one than me! He knew exactly what was going on with me! And I was influenced by the way he worked. When I ran into a problem writing and composing, I thought of Buddy and something he wrote called "For Wes," and that helped me solve the compositional problem I was having.

OK, now I'll go back to Art Blakey. Being in his group was a real musical education. In fact my entire life has been a musical education. In jazz, you learn a lot on the fly from the guys you play with, and being around these people who had changed and shaped the music and given it direction was a great learning experience for me. So working with Art and the musicians around him was special. And then, working with Max Roach was really something! So I worked with two of the great drummers. And in between, in the summer of 1969, I worked with Sonny Rollins, Buster Williams, and Tootie Heath. Sonny Rollins called me in for a rehearsal, which was really an audition, at George Braith's place on Spring Street. He asked me if I knew "Love Letters," which I didn't, so he ripped out the music right away. I played it, and he asked me "OK, let's do it in D-flat." [a very difficult key signature on piano—Eds.] And then we did "Night and Day" in E-flat and then E major, which wasn't my strong point! But he liked my playing anyway.

At any rate, they all had something I could learn from. Especially the drummers. I started out with the best of them: Billy Cobham, Lenny White, Art Blakey, Max Roach, and then on to Roy Haines, Philly Joe Jones, Elvin Jones, and Tony Williams, and then I got to play with Kenny Clarke, and Billy Higgins. So after all that, I took the drummer so much for granted, that when I encountered a new one, I had no idea what to tell them to play! I just assumed they already knew [laughter]!

AAJ: And of course you've worked for many years right up until now with another great drummer, Victor Lewis. You've highlighted the drummers. Are they the center of interest for you when you perform?

GC: I play a lot with Victor, who is a very creative player and into dynamics. We worked with Dexter back in the day, and often since then right up to the present time. I feel very comfortable with him. I do think that when I play the piano, and I'm comping, I have a close relationship with the drums. The piano is a percussion instrument, so I learned very early to work closely with the drummers.

AAJ: Let me ask you about Art Pepper, whom you worked with extensively. First of all, was Pepper part of that scene you've been discussing?

GC: No. What happened was, I moved to California, where I worked with Freddie Hubbard. He was amazing. It seemed that whatever he wanted to play, he could play. He had a lot of fire and integrity. Great sound and facility. He also played very good piano, which helped him with his concepts. And while in L.A., I worked with Art Pepper. I had previously met Lester Koenig, the founder of Contemporary Records, when I worked with Joe Henderson just before Freddie. Orrin Keepnews recorded Joe, and we did At the Lighthouse (MIlestoone, 1970). Lester was involved on that record, and he also recorded Woody Shaw's Blackstone Legacy (Contemporary, 1980) which included me on the gig. And then he got me together with Art Pepper, and we did a record called The Trip (Contemporary, 1976). And that was a milestone for me. It was the first time I got to play with Elvin Jones and David Williams and Art Pepper, all together, at the same time!

AAJ: I had no idea that Elvin worked with Art Pepper!

GC: Oh, yeah! One record we did, Live at the Village Vanguard (Contemporary, 1970), was Album of the Year in Japan. Elvin Jones and George Mraz were on that one.

AAJ: I recently listened to a CD of a concert you did with Pepper in Japan (Live in Osaka, 1979, and it blew me away! I think Billy Higgins was on drums, and Tony Dumas on bass. Incredible performance.

GC: I spent a few years with Art, and some of them overlapped with the years I spent with Dexter. I worked with Art when Tony Dumas and Billy Higgins were the rhythm section with drummer Carl Burnett. And bassist David Williams and Carl were in the rhythm section. At the time, another pianist would sometimes play with Art, a guy from Bulgaria, Milcho Leviev. I think Art may have done some work with Stanley Cowell. I remember Hank Jones also worked with Art.

AAJ: Did your first work with Dexter occur after he came back from Europe in the late 1970s?

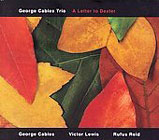

GC: Yeah, it was around '77, and he had already done the famous record Homecoming at the Vanguard, which had Woody Shaw and his band on it. Ronnie Matthews was the pianist. Woody Shaw and Todd Barkan recommended me to Dexter. So when Dexter came out west and played in L.A. and San Francisco, I played with Dexter at the Keystone Corner in the latter city. We hit it off, and that was probably one of the greatest musical relationships for me. I think of Dexter as my musical father. For me, Dexter and jazz are almost synonymous. He represents what jazz is. That is what inspired my album, A Letter to Dexter (Kind of Blue, 2006).

AAJ: That's quite a compliment, even for Dexter! So what was it like to work with him?

GC: It was just fun, because he wanted to be leader and also just wanted to play. He was very creative and arranged our choruses. We had a quartet that really developed, with Rufus Reid on bass and Eddie Gladden on drums. Dexter had a few specific things he wanted, and he would tell you that, but he would also just roll with the band. We became an incredible group because we were really tight. Dexter finally felt he had his own group that had his own voice. The rhythm section really worked well together.

GC: It was just fun, because he wanted to be leader and also just wanted to play. He was very creative and arranged our choruses. We had a quartet that really developed, with Rufus Reid on bass and Eddie Gladden on drums. Dexter had a few specific things he wanted, and he would tell you that, but he would also just roll with the band. We became an incredible group because we were really tight. Dexter finally felt he had his own group that had his own voice. The rhythm section really worked well together. I remember that one day he gave me a piano solo on a ballad, and the band suddenly stopped playing! I had no accompaniment, and I just started playing my solo piano, and I wasn't used to doing that, but I kept finding things to play and really stretchin' it out and being fairly free, and playing rubato, and out of tempo. And Dexter encouraged me for taking that risk, and I'm grateful for that because he helped me find out what I can do playing solo.

AAJ: That's interesting, because you had already been playing for many years with some of the greats. But something clicked in, and you got into a new groove.

GC: I had been playing with Joe Henderson and Freddie Hubbard using electronic piano and keyboards, so with Dexter, I returned to playing acoustic piano, which I really liked.

AAJ: You could say that Dexter was a game changer for you. When you think back, were there any others who had a similar transformative influence on you?

GC: Well, with Art, as well as Frank Morgan, I started playing duets. And that helped me a lot to grow and develop. And Art started me thinking on how to play ballads. His idea was that when you play a ballad, you don't double up, you don't bounce, you just stay with the tempo that you started with. He thought of a ballad as a contrast to the other tunes that swung or had a bounce. So that idea stayed with me. And then between Art and Dexter, and also Miles, who I never worked with but always listened to, I developed a concept of playing ballads.

AAJ: Now, you have often stated that you listen to groups more than you listen to pianists, which is certainly the case with your desert island selections!

GC: There was a time I listened to pianists. I listened to O.P.—Oscar Peterson—and Wynton Kelly, but the majority of my listening was to groups. And I would listen to the pianists in the groups, like Wynton, or Red Garland, or Herbie Hancock with Miles' groups, and McCoy with Trane. And I'd listen to their concepts, but what was most important to me was that these guys were playing as members of the group. The music was made by the whole group working together. And Miles was the captain of the crew. Or Trane was the captain of his ship. And I also noticed how each man made a specific contribution. When a band changed a member, the music changed! And the great band leaders did a great service to the music by allowing it to change with the new band members. With Miles you could really hear that when he got Herbie, Ron [bassist Ron Carter], and Tony [drummer Tony Williams.] That rhythm section did a whole new thing for Miles, or actually extended his ideas.

So what I really liked and listened to was the way the band worked together. The music, the dynamics, the direction, the colors, and so on. When I played, I would think not only in terms of chords, but in terms of the colors, the sounds. And I got a lot of that from Miles. It seemed that he was painting a picture. When you heard them in person, you got the feeling there was magic happening right in front of your eyes. And with Trane it was the energy and the sound colors, that Trane or McCoy would lead you into, like sometimes McCoy'd play the piano like a drum. And all those colors, not like this is a B-flat minor chord, but there was more than that. You could hear that center, but you'd also hear all the colors around it. So of course I could hear the piano, but it was the overall band that interested me most.

AAJ: Speaking of Coltrane, in his late career, he started going very far out musically. I'm interested in how musicians vary between those who stick pretty much to traditional modes versus those who go outside the canon. You seem to stay within the tradition, while being quite inventive and creative. You did some time with Archie Shepp, who was into free jazz and other modalities.

GC: I worked with Archie, but the way I heard him, he actually went back to basics, back to the roots. He would go back to the blues. I mean, he would play "Giant Steps," but where some guys would be dealing with the trees, so to speak, he seemed to be dealing with the forest. Sometimes I'd wonder if it was my imagination what I'd hear him doing! But he wasn't into Ornette's kind of free jazz so much.

AAJ: Do you know what makes a musician stay close to the shore as opposed to going out into the vast ocean of musical possibilities?

GC: I personally do like to experiment with colors and sounds, but I'm always thinking of the tonal center. But, still, I can step to the left or the right or make the music more chromatic, like V to I with a flat II to I, that's just a beginning. But I always wanted to play against the chords as well as within them. Woody [Shaw] was really one for that! I always like playing against the chord with Woody, but he would often ask me to "stay home" [stay with the original chord] because he felt his contrasts could be heard better that way. But I still like to go in and out of the chord, against the chord. It also depends on the group. If I'm playing with The Cookers and they're playing "The Core," I vary playing outside the chord or with the chord. With harmony, it's not just the chord itself, it's things that the chord can imply. It depends on the context, how you're getting from one place to the next. Another good example is Sonny Fortune. When you play with him you step outside, and it's a way to stretch your concept, like seeing and hearing things in a different way. It gives you a different perspective, and that's exciting. I like that.

New Projects

AAJ: Let's try to bring it up to the present a bit now. In the last couple of decades, you've been very productive. And despite having had some serious medical issues, you've recently made a number of recordings as a leader.

GC: Yes, I've been excited about that. I have had some health issues that made things seem more urgent. I've been fortunate all my life to have been able to play with some really great musicians. More recently, I've been writing more as well as exploring some of the things that I've written before. So my last record, My Muse (HighNote, 2012), which is dedicated to my late partner Helen, is a trio record, and pretty topical and lyrical at that.

GC: Yes, I've been excited about that. I have had some health issues that made things seem more urgent. I've been fortunate all my life to have been able to play with some really great musicians. More recently, I've been writing more as well as exploring some of the things that I've written before. So my last record, My Muse (HighNote, 2012), which is dedicated to my late partner Helen, is a trio record, and pretty topical and lyrical at that. AAJ: That's a wonderful recording by the way. It's so listenable and expressive. When I heard it, I thought of some pianists you haven't mentioned, especially Tommy Flanagan and Kenny Barron, in terms of the combination of lyricism and a tight rhythmic pulse. In your opinion, is that a fair comparison to make?

GC: Those are great pianists, and I'm very grateful to be mentioned in the same breath as them. Kenny is one of my favorite pianists and a great influence on me from years ago. I first became aware of him when he was with Dizzy Gillespie and Freddie Hubbard. He is both a great writer and pianist, and as time goes on, the added experience has contributed to his elegance.

AAJ: "Elegance" is the word I was looking for to describe Tommy and Kenny as well as your new album.

GC: Yet, at the same time, I don't want to be exactly like them. They have their territory staked out. I don't want to compete with them. But Kenny is just a great pianist, and I love the way he touches the piano...

AAJ: I didn't mean to imply that you were imitating them, only that you share a certain tradition in common.

GC: I think that we're related in some ways. Kenny, like me, likes to go outside the chords. I think we have similar influences. For example, Art Tatum is our pianistic grandfather. And I love the piano. I've been exploring that in another record that we're working on, that we're calling "Icons and Influences," so I can reach back a bit and play some music, let's say, by Dave Brubeck or Duke Ellington and Mulgrew Miller and Cedar Walton. Cedar had a big influence on me, and who I identify with because of his work with various rhythm sections. I remember reading that he didn't want so much to be thought of as a great soloist as he wanted to be a great pianist. Like me, his emphasis was on the group. But now I enjoy the whole gamut: solo, duo, trio, quartet, the smaller groups, which makes it easy for me to make my voice heard.

So, I have my various projects coming up. I have a songbook with some of what I've written, but in different settings, like with the young vocalist Sarah Elizabeth Charles. I hope to do part of that in November in my gig at Dizzy's Club Coca Cola. We'll do some trio, some songbook, with Sarah, Steve Wilson, Victor Lewis, Essiet Essiet. I had been using Steve Berrios as a percussionist, who recently passed away, so Steve Kroon will be there instead. But I'm working on some new pieces as well. And then there's my association with The Cookers. Like somebody said, "There's snow on the roof, but there's still a lot of fire in the furnace." Guys like Billy Hart, Cecil McBee, Billy Harper, Eddie Henderson. Among the younger guys there's Eddie Weiss. Craig Handy, Gary Bartz. We've had a close relationship over time, and each one of these guys has been a strong influence on my musical life.

And of course, the Dexter Gordon legacy is very important to me. At the February 2014 Dexter Gordon Birthday event at Dizzy's, the rhythm section is going to be Victor and probably Rufus. For the front line, I have in mind Brandon Lee, Jerry Weldon, Walter Blanding, and Joe Locke. It depends a lot on who's available. And then there's "The Art Pepper Legacy," a brain child of Gaspare Pasini, an Italian alto saxophonist. We've used Carl Burnett for that. We had been using bassist Bob Magnuson, but he's had some physical ailment, and I think he's had to retire from playing gigs. We're all alumni of Art Pepper's groups. But we've used Essiet, and it turned out very, very nicely.

So I have my hands in a lot of things. And then I'm teaching an improv ensemble at the New School. In the past, I've had a Herbie Hancock ensemble in which we played the music of Herbie. This year, it's the improv ensemble, which is pretty open as to which music. So far, I've brought in a McCoy Tyner piece, a couple of my own pieces, some Charlie Parker, a great variety.

AAJ: What is the instrumentation?

GC: This year I have alto, tenor, piano, bass, drums, and guitar.

AAJ: A lot of the best jazz training happens at the New School.

GC: Right. There are great instructors who really care what happens with the music and the young musicians.

AAJ: Things are pretty exciting for you.

GC: Yeah, they are. I'm busy, I can tell you that.

Getting Personal

AAJ: I always ask the musicians about their personal life, because, as Charlie Parker said, "If you haven't been through it, it won't come out of your horn." You mentioned your partner Helen. Tell us about her.

GC: Helen passed away from pancreatic cancer in November, 2010. I still feel her presence. We were together for 28 years. No kids, probably by choice.

AAJ: I know you've had your own medical issues. I understand you're doing very well right now.

GC: I was on dialysis for about five years, which of course made traveling a little more difficult. I was on hemodialysis, so I had to be on the machine four hours each of three days a week. But you do what you have to do, but then I had a kidney and a liver transplant.

AAJ: Were the two transplants done together?

GC: Yes. It's like when those utility guys come out on the street to fix the electric or gas lines underground. They open up the street, and close it up, and then another crew comes in and does the same thing! So the liver team comes in, they do their work, they close you up, and then the kidney people are right behind them! I had it done at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York. The first was in 2007 and then in 2008 they replaced the first kidney transplant. I can't get over how well the new kidney has worked, and in my last tests, everything was perfect!

Not too long ago, I went to the 20th anniversary of the Mt. Sinai liver transplant unit, and I was so impressed with the progress they've made in that field. And they have to deal with the fine line between medical care and experimentation. There are many risks involved. The dedication. So many critical decisions to make. And when I was there, they really took great care of me.

AAJ: Were any of the medical staff into jazz?

GC: Yes, a few of them were, and one in particular was into piano music.

AAJ: Jazz is about the story of our lives. And Coltrane famously said, "Music is my spirit." Having lived life fully, and with all the experiences and issues you've had, and all the remarkable people you've met, do you have any over-riding perspective on life?

GC: I'm just really amazed at all the wonderful things that have happened in my life. I try to take things as they come and just try to be the best person that I can be, and just do what I'm supposed to do now. You know, you have times in your life when you kind of screw around, but at this time in my life, I just try to take things as they come. There are things that I just can't define, but they're there, and I just try to go with them. I don't understand everything, but I just try to be positive. The spirit is in everything. Life is all around us, and you just try to be in tune with everything. Basically, I just try to be in tune with what happens, and music is a great part of that. Music is how I express myself and whatever it is I have in me. I'm not arrogant enough to say, "I know this is what it's all about." Life is a wonder, and I'm a small part of that, and I'm just trying to be whatever I can be.

AAJ: Being in the now, in the zone, in the spirit, in the wonder. It's like being in a great jazz group!

GC: Right! Exactly! I've had wonderful friends. I've been blessed by being close to some of the greatest musicians in the world. Still, sometimes, when I think about it, I wanna say, "Why me? Why did this happen?" But I never take my blessings for granted.

Selected Discography

George Cables, My Muse (HighNote, 2012)

Dexter Gordon, Night Ballads (Uptown, 2012)

Art Pepper, Live in Osaka, 1979 (Widow's Taste, 20012)

George Cables, A Letter to Dexter (Kind of Blue, 2006)

George Cables, Alone Together (Groove Jazz, 2000)

Dexter Gordon, Live at Carnegie Hall: Complete (Columbia Legacy, 1998)

George Cables, Skylark (SteepleChase Records, 1995)

George Cables, By George (Contemporary Records, 1987)

George Cables, The Big Jazz Trio (Eastworld, 1984)

Art Pepper and George Cables, Goin' Home (Galaxy, 1982)

Art Pepper, Live at the Village Vanguard (Contemporary Records, 1980)

George Cables, Cables' Vision (Contemporary Records, 1979)

Bobby Hutcherson, Conception: The Gift of Love (Columbia, 1979)

Art Pepper, Friday Night at the Village Vanguard (Contemporary, 1977)

Art Pepper, The Trip (Contemporary, 1976)

Art Blakey, Child's Dance (Prestige, 1972)

Curtis Fuller, Crankin' (Mainstream, 1971)

Max Roach, Lift Every Voice and Sing (Atlantic, 1971)

Joe Henderson, At the Lighthouse (Milestone, 1970)

Woody Shaw, Blackstone Legacy (Contemporary, 1970)

Photo Credits

Page 2: Steven Sussman

Page 4: John Kelman

Page 6: Richard Conde

< Previous

Roots

Comments

Tags

George Cables

Interview

Victor L. Schermer

United States

Art Blakey

Art Pepper

Freddie Hubbard

Woody Shaw

Dexter Gordon

John Coltrane

Miles Davis

Billie Holiday

McCoy Tyner

Art Tatum

Mercer Ellington

Count Basie

Milt Hinton

Brook Benton

James Brown

Charles McPherson

Paul Jeffrey

Ray Copeland

Thelonious Monk

Ray Bryant

Oscar Pettiford

Bill Hardman

Sam Dockery

Dave Brubeck

Mose Allison

Charles Mingus

Eric Dolphy

Ornette Coleman

Marian McPartland

Birdland

Billy Cobham

Artie Simmons

Rudy Williams

eddie daniels

Johnny Coles

Jim Harrison

Lenny White

Booker Ervin

Billy Hart

Larry Ridley

Jimmy Owens

Buddy Montgomery

Buster Williams

Sonny Rollins

Wes Montgomery

Max Roach

George Braith

Kenny Clarke

Billy Higgins

Victor Lewis

Lester Koenig

Joe Henderson

Orrin Keepnews

David Williams

Village Vanguard

George Mraz

Tony Dumas

Carl Burnett

Milcho Leviev

Stanley Cowell

Hank Jones

Ronnie Matthews

Todd Barkan

Rufus Reid

Eddie Gladden

Frank Morgan

oscar peterson

Wynton Kelly

Red Garland

Herbie Hancock

archie shepp

The Cookers

Tommy Flanagan

Kenny Barron

Dizzy Gillespie

duke ellington

Mulgrew Miller

Cedar Walton

Sarah Elizabeth Charles

Dizzy's Club Coca Cola

Steve Wilson

Essiet Essiet

Steve Kroon

cecil mcbee

Craig Handy

Gary Bartz

Brandon Lee

Jerry Weldon

Walter Blanding

Joe Locke

Bob Magnuson

Concerts

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.