Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Ed Bradley: Journalist and Jazzman

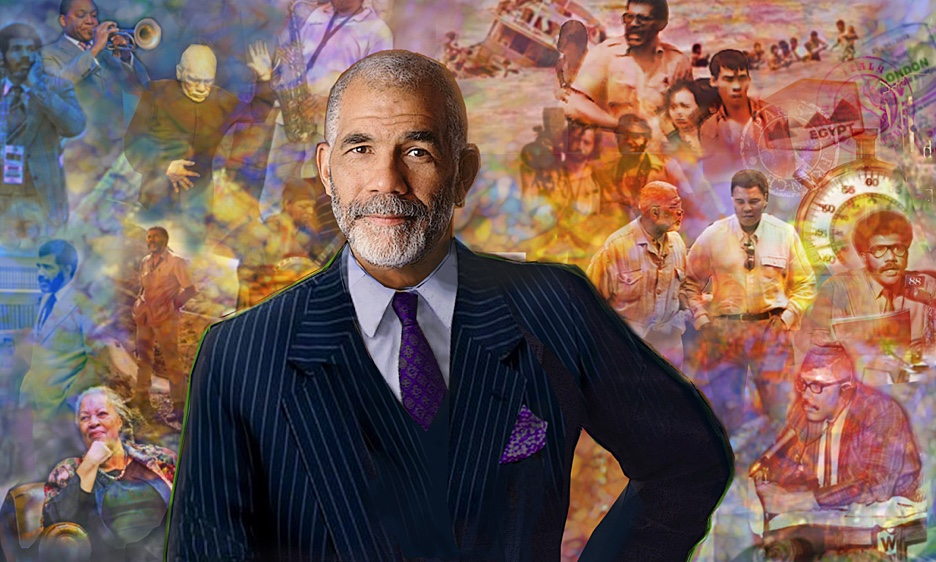

Ed Bradley: Journalist and Jazzman

I never got jazz. It was something the generation ahead of me listened to... Then all of a sudden I heard Concert by the Sea.

Some may not know that Bradley, 61, is also a longtime jazz fan. Before he embarked on a journalism career that has won him a Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, the Paul White Award from the Radio and Television News Directors Association, as well as Emmys and a Peabody Award for his reports on "60 Minutes," he was a jazz disc jockey, back in the day, in Philadelphia, making $1.50 an hour spinning the records of John Coltrane, Miles Davis and Billie Holiday. That gig, he admits, was done out of joy for the music, while he earned his living by day as a teacher.

His whole life changed when he decided to go into journalism, but his passion for jazz remained, and he got back into radio about a decade ago through his association with Jazz at Lincoln Center, and back into a radio job hosting Jazz from Lincoln Center, now in its 10th season.

The program—which earned its own Peabody Award—can be heard mostly on National Public Radio (NPR) stations and has recently been picked up by other commercial stations across the country.

But there was a subtle shift this season, a shift that might be another blow to jazz music in the United States. NPR no longer has anything to do with funding the "Jazz from Lincoln Center," and is doing away with other long-format shows, some of them jazz. Bradley's show will flourish. It's still distributed to many NPR stations, but it is done by WFMT Radio Networks, which handles the distributing and marketing. Is NPR, once one of the tried-and-true places people could go to find jazz music, turning its back a bit on the great American art form?

Perhaps so. The decision, at minimum, has created a further erosion of jazz airplay.

"NPR decided to go another direction with their programming. I think it's a mistake, but that's what they wanted to do," said Bradley. "They got some new people on board and decided they don't want to do this kind of show anymore, as well as some of the other longer-format shows that they do, and they went off in a new direction. I think they made a big mistake, but we have a continuing outlet for our broadcast, and in fact we're growing."

But it's another place where jazz has lost a little ground in America.

There has been a catch-22 regarding jazz music on the airwaves. Programmers say the desirable demographic doesn't listen to the music, so they won't play it. Because it's not being played, it can't reach people. The music needs to be out there, so that people have a choice.

"It's a matter of what you're exposed to. There's not a lot of jazz on the air, so fewer people do hear it," said Bradley. "If you don't get airplay, it's hard to sell the music."

"They will supply it if there is a demand for it. But you're caught in that vicious circle there. How do get the demand if there's no availability on the air? Because access to the airwaves creates demand for the product."

Jazz musicians feel that way too, knowing they're swimming upstream against the current of the music industry. Drumming legend Elvin Jones, in an All About Jazz interview earlier this year, lamented, "nowadays what people hear they really don't have any control over it. And that's the problem. I don't think it's the music. The music is beautiful," he said. "But if I can't have a choice if I turn on my radio or television or go in a record store and there's nothing there but, bam-bam-bam-man, or cussin' or calling everybody a motha-something—that's not to my taste. The music doesn't have anything to do with that."

"But I just don't believe that people who perpetrate that kind of fraud will last," added Jones. "Just like EnRon has come tumbling down. Everybody gets found out sooner or later."

Bradley also sees radio, in general, as too similar across the nation, resulting in a loss of the cultural flavors one could sample from region to region.

"There's been such a constricting of radio in this country. You can leave New York and go to Chicago or go to Dallas, and you'll hear the same songs. Because the stations are owned by the same company, and they do the same programming with the same songs. Some of them don't even have live disc jockeys; no people in Dallas, telling you what it's like in Dallas. There are some stations that do, but there are many stations that don't. That kind of regionalism that you heard in this country, we're losing.

" New Orleans is a perfect example. You would go to New Orleans and there would be people who are big hits, big stars and everyone knows them in New Orleans, but they rarely escape New Orleans, parts of Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi. They were regional hits. Every once in a while you would get someone who would escape. Going back to the 50s and 60s. Ernie K-Doe had "Mother-in-Law." It was a big hit. But everybody knew K-Doe in New Orleans," said Bradley.

"There are all kinds of groups like that, and musicians like that, jazz musicians like that. We lose our identity when it all becomes homogenized."

There are people who will never like jazz, and those that always will. In the vast middle ground, there is the potential for many more fans, if they only had a fair chance to be exposed to the music. For so many jazz fans, there was one special moment when jazz broke through the skin, poked into a vein and traveled to the heart. For me, it was "My Funny Valentine" from Miles' Cookin'. For Ed Bradley it was "Teach Me Tonight," from Erroll Garner's Concert by the Sea.

"I've been around jazz all my life. But up to a certain point I regarded it as my father's music and my uncle's music, because they all played it and it was what they liked. But it wasn't my music," he said. "I guess the first 10 years you weren't aware of music for yourself. But as you approach those teenage years, you stake out your own identity. In those days, I think it happened later than it does today."

But that changed with exposure to the classic Garner album. "For me, it was my Rosetta stone. Because I never got jazz. It was something the generation ahead of me listened to. It wasn't my music. I didn't understand it. Then all of a sudden I heard Concert by the Sea. Particularly "Teach Me Tonight." All of sudden it made sense to me." He was 15 at the time and remained a fan.

In his 20s, he got the side job at WDAS in Philadelphia playing jazz music for fun, certainly not for profit.

"The idea that I could go to a station and open the cabinet doors of what we called the library and pull out music present and past and play what I liked to play, music I liked to hear, and that there were people out there listening to my taste in music —Man, it just didn't get better than that. What more could you want? A friend of mine said, 'If I turn the radio on and I hear Billie Holiday, I know you're on the air,'" he said with a gentle laugh.

Being a disc jockey also contributed to Bradley broadening his tastes in jazz. How? The word "exposure" is once again the key.

"My tastes at that time, I guess this would be 1964-65, reflected where I was. I was 24, 25 years old. I was into Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Yusef Lateef, Horace Silver, Mal Waldron, younger, hipper guys. When I became a disc jockey, I would get phone calls. Listeners would call up and say, 'Hey. How come you don't play Count Basie?' Well, Count Basie wasn't happening for me, but because I would get people who would ask for it, Count Basie or Duke Ellington, I would say, 'Let me see what we have here on Count Basie. Wow, he has a lot of albums.' And then Duke Ellington. 'Whoa, man. Does he have a lot of albums! Let me play some of these and see what I hear in them.'"

"Then I started playing big bands. From there, it took me to other big bands. Playing people like Coltrane and realizing there was someone who came before Coltrane. Where did he come from? Then somebody asked me about Dexter Gordon. I had never heard of Dexter Gordon. I pulled out an album and heard "Scrapple From the Apple," and said 'Whoa, man.' So I started looking for Dexter Gordon and where did he come from? That took me to people like Ben Webster, Lester Young, Charlie Parker, Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt.

"What I do now as a journalist, when I'm doing a story, I have to do homework. I have to read everything I need to read about that story, so I know what I'm talking about. When I was a disc jockey, I had to do homework to find out about this music that was really new to me. So, I did a lot of listening on my own and exploring people whom I didn't really know a lot about, and discovered some great musicians. I just loved it. It's never stopped. My tastes are very eclectic and catholic in the universal sense. I like music and I see jazz as one category in music. I like all kinds of jazz."

As a young man eying his future, Bradley had to stop doing what he liked in order to follow bigger pursuits.

"I could never make a living on what they paid me at WDAS. I made $1.50 an hour, tops. Maybe by the end I got up to about $2 an hour. I was teaching school during the day and working at the radio station at night. I had come to a point where I had to make a decision to do one or the other. I was also doing some journalism. Looking down the road, I didn't see a promising future as a jazz disc jockey. I could have a lot of fun, but I wasn't going to be able to live the kind of life I wanted to live. And I didn't think I could do that as a teacher either.

"Financially, I wanted more than that. Emotionally, in terms of what I wanted to see in my life and in the world, I wanted more than being in a fixed place everyday. I didn't realize it at the time, but I realize it now. What was driving me was that sort of wanderlust. If you're a teacher, you go to the classroom every day. If you're a jazz disc jockey, you go to the radio station every day. I have a wanderlust to see different places, travel the world, do things like that. That's what made me go into journalism."

Bradley probably thought, with his career blossoming and his plate full with the success of "60 Minutes" that his days of radio were long gone. Not so.

"I got a phone call one day from Gordon Davis, who was on the board of Jazz at Lincoln Center. At that time, I think he was chairman of the board of Jazz at Lincoln Center. He said, 'I'd like to talk to you about coming to serve as a board member and I'd like you to do a radio show for us.' I'm not fond of boards, but I thought this was a good one. I thought it was some way I could give back to this music that has given me so much. So I said OK. I was so naive, I thought what I would do was show up once a week, bring some records and play them," he said, chuckling. "It turned out to be a very different kind of radio show, but one that I love doing."

So Bradley plans to continue for the foreseeable future, and NPR or no NPR, he has confidence in the viability of the Lincoln Center program. In general, despite radio's disrespect for American's wonderful art form, Bradley thinks jazz music is in good shape.

"I see the music as vibrant," he said. "Go to the record store. There's a wall full of historical stuff. Every album John Coltrane made and didn't make. Same for Miles Davis. They put out anything that is available. But you also see plenty of new material by young artists.

"I went to see Illinois Jacquet last night and his big band. Some of his musicians look like they could have been in high school. I would say most of the musicians in his band are in their 20s. I think it's an alive, vibrant art form."

< Previous

Drummer Tom Rainey

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.