Home » Jazz Articles » Profile » BassDrumBone and the New Haven Jazz Renaissance

BassDrumBone and the New Haven Jazz Renaissance

It seems appropriate that an ensemble with a metaphysically evocative name should have been formed in New Haven. The city had been founded by Puritan visionaries who laid it out as a grid of nine squares—an ideal city traced in right angles and traversed by "metaphysical streets," as Wallace Steven described them in An Ordinary Evening in New Haven. But by the 1970s the physical town was far removed from any metaphysical ideal, having been eroded by the combined effects of deindustrialization, the 1967 riots, the disruption and displacement of neighborhoods by the Oak Street Corridor and other urban renewal projects, and the move of second generation ethnics out of the city and into Hamden and other inner ring suburbs. Yale, originally founded to educate Puritan divines, was and still is a dominating presence in the city's economic and cultural life.

Culturally, there was more to New Haven than Yale, although one might have to look to find it. The city had been home to a thriving jazz culture in the 1950s and early 1960s. Uptown, Dixwell Avenue and the surrounding neighborhoods had many clubs where local and national musicians played: The Monterey Café; The Play-Back on Winchester Avenue near the gun factory, run by bassist and Yale graduate Willie Ruff; The Musicians' Club; Lillian's Paradise on Hamilton Street; McTriff's and others. Downtown theaters like the Poli and the Bijou frequently featured jazz as well. As the 1960s wore on, though, jazz in New Haven—as in many other places—went into eclipse.

In the 1970s, New Haven's music scene experienced a renaissance. The city attracted a number of forward-thinking musicians, whether through Yale or through the creative activity that was growing up around and outside the university. George Lewis came to Yale from Chicago to study philosophy; before he obtained his degree in 1974, he had taken a year off to return to Chicago and play with the AACM. New Jersey native Anthony Davis, who met Lewis when both were freshmen at Yale in 1969, majored in music there and formed bands with Lewis, bassist Wes Brown and others; saxophonist Jane Ira Bloom arrived at Yale from Boston, graduating in 1977. In the early 1970s, Wadada Leo Smith came to the area and formed New Dalta Ahkri, a group that included Davis on piano and Brown on bass and Ghanian flute, and set up his Kabell Records label. Smith, along with Hemingway, Brown, reed player Dwight Andrews and vibraphonist Bobby Naughton, also formed the Creative Musicians Improvisers Forum, a non-profit group modeled on the AACM. Mark Dresser arrived from San Diego in 1975 and stayed for a year or two; his neighborhood was home to Hemingway, Andrews, Pheeroan AkLaff, and Jay Hoggard. Anthony Braxton, whose archive is in New Haven and who now lives in a suburb of the city, came to New Haven to play with Smith in 1974 and eventually moved there, staying for several years.

Like Smith, Dresser, Lewis and Braxton, Anderson and Helias came to New Haven from elsewhere. Anderson was originally from Chicago, where he and Lewis had been classmates at the University of Chicago Lab School. He began playing trombone in the fourth grade—along with Lewis—and in his teens was exposed to the music of the AACM. He was introduced to the New Haven creative music community by Dresser after they'd played together in New York, where Anderson had been living since 1973. Helias in the mid-1970s was a graduate student at the Yale School of Music, having come there in 1974 after obtaining his undergraduate degree from Rutgers University. While a student at Yale, he began playing in bands with Smith and Davis.

Unlike Anderson and Helias, New Haven native Hemingway had always been there, more or less. In winter, 1973, he briefly went to Boston to the Berklee College of Music but dropped out; he returned to New Haven, where he gave drum lessons, played club dates and gave a series of solo concerts each of which was dedicated to a significant figure in the history of jazz drumming. He met Davis through an ad he placed in Rolling Stone when he was looking for a pianist and bassist and played in the collective group Advent, which in addition to Hemingway and Davis included George Lewis, saxophonist Hal Lewis, and bassist Wes Brown. It was through Davis that Hemingway met Helias in 1974, when they jammed together at Davis's invitation; with the addition of vibraphonist Jay Hoggard, they eventually became the Anthony Davis Quartet. Hemingway subsequently met Anderson through Dresser. Before they formed their trio, the two worked together on one of Hemingway's early large-scale compositions, a series of eight duets inspired by the paintings of David Pallian, which Hemingway had composed for varied instruments.

Anderson, Helias and Hemingway first played alone together as a group in autumn, 1977, at a concert Hemingway performed for his students at New Haven's Educational Center for the Arts. Hemingway put the group together for the occasion, and there hadn't been much in the way of preparation—just a rehearsal a few hours before the performance. But the three seem to have established a robust synergy right away. They went on to play at least one other early, local concert, in Yale's Battell Chapel—the place where The Sam Rivers Trio had played and recorded the legendary "Hues of Melanin" suite in November, 1973.

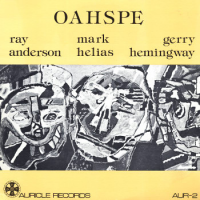

The group first appeared on record in 1978 with the track "Speak Brother," a cut included on Hemingway's Kwambe LP, the first release on his Auricle label. This was followed by a full-length, self-titled LP on Auricle—the label's second release.

OAHSPE the album was recorded in November, 1978 at the Educational Center for Arts. On all five tracks, Anderson, Helias and Hemingway demonstrate a deep congruence and an excellent musical chemistry. The three share a musical language rooted in the swing and swagger of post-bop that's further informed by a modular sense of structure and a pronounced sensitivity to color. The pieces go beyond the standard head-improvisation-head format to intersperse composed passages with more open passages of collective improvisation or soloing; the composed segments are frequently built up from short, repeating melodic cells for trombone and double bass that are staggered or layered in unison. Although all three musicians get solo space, the overall approach is to create a collective sound—it's literally woven into the texture, which tends toward a polyphonic braid of individual yet commensurate voices. Having the two melodic instruments overlap at the lower end of the pitch range makes for subtle color shadings; all of it is undergirded by Hemingway's always-pertinent drumming. For a debut it's an assured recording, and one that holds up well nearly forty years later.

OAHSPE the album was recorded in November, 1978 at the Educational Center for Arts. On all five tracks, Anderson, Helias and Hemingway demonstrate a deep congruence and an excellent musical chemistry. The three share a musical language rooted in the swing and swagger of post-bop that's further informed by a modular sense of structure and a pronounced sensitivity to color. The pieces go beyond the standard head-improvisation-head format to intersperse composed passages with more open passages of collective improvisation or soloing; the composed segments are frequently built up from short, repeating melodic cells for trombone and double bass that are staggered or layered in unison. Although all three musicians get solo space, the overall approach is to create a collective sound—it's literally woven into the texture, which tends toward a polyphonic braid of individual yet commensurate voices. Having the two melodic instruments overlap at the lower end of the pitch range makes for subtle color shadings; all of it is undergirded by Hemingway's always-pertinent drumming. For a debut it's an assured recording, and one that holds up well nearly forty years later. "Gyro" opens the recording with a swinging unison melody for bass and trombone, and then decomposes into repeating cells for separate voices, breaking into solo spots for Hemingway's drums and an Anderson solo over broken walking basslines. "Albert," a homage to Albert Ayler, features a keening Anderson solo that's bluesy and abstract at the same time. "Beef" has Hemingway briefly switch to vibes for a three-voiced counterpoint of interlaced short phrases, and then moves into a smeary trombone solo over walking basslines. The asymmetrical lines and implicit march rhythms of "Sextant" seem to have been inspired by Anthony Braxton's work of the mid-1970s. The final track, "Gibberish," constructs a whole out of fragmented bits of swing, free improvisation, and extended techniques for bowed bass and trombone.

Not long after the album came out, the group dropped its name. It may simply have been because it was hard to pronounce, as Hemingway told Graham Lock, or it may have been—as the BassDrumBone website relates—because a California group dedicated to Newbrough's book, with which the trio had no connection other than the coincidence of name, claimed that Jehovah, with whom they were in contact, suggested that the musical OAHSPE change its name to "Snowflake." (And what is one to do, when music criticism comes from such a high authority?) Either way, the group's second album, issued in 1984, came out under Anderson's name, while subsequent releases have been under the BassDrumBone name.

In the context of its 40-year history, BassDrumBone's New Haven residence was short-lived. Helias had already joined Anderson in New York in 1977—even before the trio played its first concert—and Hemingway followed suit in 1979. The larger New Haven creative music community itself was dispersing at the end of the 1970s. Some of the musicians had graduated from Yale and were ready to pursue careers elsewhere; others simply left for other opportunities. That phase of the city's creative life came to a close. Eventually Wesleyan University, just north of New Haven in Middletown, Connecticut, became a major focus for creative music in the state, though New Haven continues to have an active scene of its own. Heard four decades later, the OAHSPE album is one of a number of durable, still-exciting recordings to have come out of a fertile, if relatively evanescent, moment when this small postindustrial city was the nexus of a remarkable collection of talent.

Photo credit: Jordan Hemingway

< Previous

Converging Tributaries

Next >

Meet H. Alonzo Jennings

Comments

About BassDrumBone

Instrument: Band / ensemble / orchestra

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

BassDrumBone

Daniel Barbiero

Profiles

New Haven

Yale

Mark Helias

Gerry Hemingway

Ray Anderson

OAHSPE

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.