Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » A Conversation with Music Author Alan Light

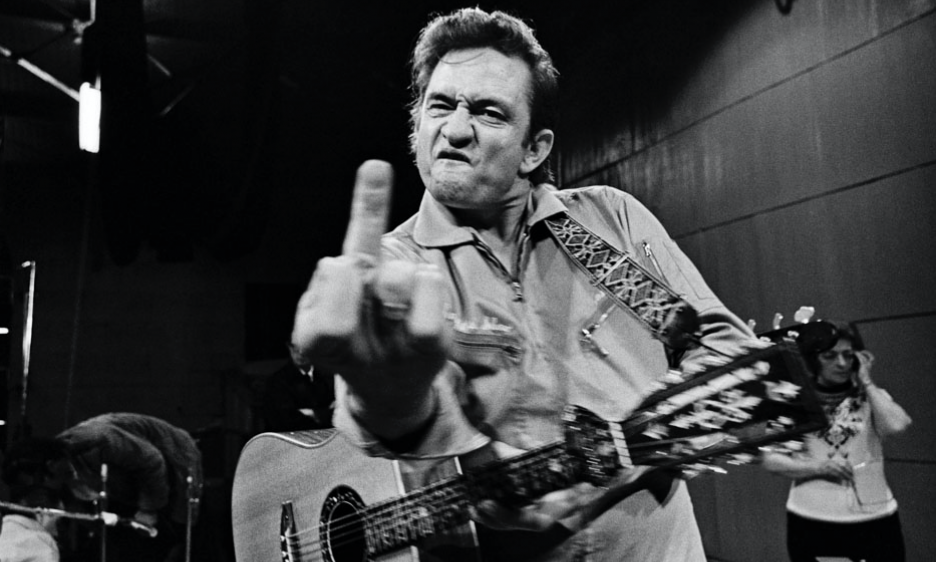

A Conversation with Music Author Alan Light

All About Jazz: What made you want to write about Johnny Cash?

Alan Light: I have loved Johnny Cash's music for most of my life, and been privileged to write about him several times in my career, including one of the last major interviews of his life. In this case, I was approached by Smithsonian Publishing, who were working on this book along with the Cash estate, and they asked if I wanted to take on writing the text—so much as I'm happy to have any reason to write about Cash, this time it's because the project was brought to me!

AAJ: What sort of goal did you have when you wrote this book?

AL: This book is primarily about the images—the photos and images from Johnny Cash's personal files and archive. That was the focus of the project, and the real reason it's exciting or new. My goal was to tell his story in a concise and clear way; I didn't have the space (or the time) to do a comprehensive or definitive biography, and some great ones (including his two autobiographies and Robert Hilburn's biography) already exist. My job was to provide context for the images and round out the story of his life and legacy, try to explore some of the themes in his life and his work, all to augment these great pictures.

AAJ: Taking into account the amount of books that were written about Cash and he himself has written two autobiographies what has left been unsaid about him?

AL: See answer above. I didn't really set out to tell an untold story or uncover new details or mysteries in his life. What I wanted to do was paint a picture of Cash, give a sense of him and his work, in a way that would make the photos and other illustrations in the book feel richer and fuller. Also, I suppose that over time, his significance and influence continue to evolve, so any new examination of his life is going to have a new perspective.

AAJ: Similar to the Nina Simone book when you were given documents and research for the documentary you were handed documents and photographs from the Cash estate's archives, many of those previously unseen. How did you structure the story based on these documents and photographs?

AL: The Simone book was really built out of the documents (interviews, transcripts, diaries, etc)—I was using those primary sources to construct the story. With Cash, the photo side and I were working more in parallel. I didn't really use the archival material here as a basis for the narrative, but was writing with the idea that my words would be running alongside and in conjunction with the images, and that I was fleshing out the story that they would be telling.

AAJ: Could you compare and contrast both artists, Nina Simone and Johnny Cash? There are similarities where they approximately lived and worked in the same time periods, they both championed for the rights of their communities and the downtrodden, and yet they led controversial private lives.

AL: Interesting question. Simone was a much more conscious and intentional activist—she was directly political and saw that as the primary role of and function for her work. She also positioned herself as a more extreme activist (when she met Martin Luther King, she made a point of saying "I'm not non- violent"). Cash certainly saw himself as an entertainer, Nina first, but always acted with conscience. His support for prisoners, Native Americans, the impoverished—his hope of being a voice for the voiceless—informed much of what he did, articulated most clearly, of course, in the lyrics of "Man In Black." But he also never voted, met with US Presidents of both parties out of respect for the office, and I think in general saw himself as more of a social force than a political force.

AAJ:You had an opportunity to interview Cash on several occasions. Please talk about the impressions you had when you interviewed Cash.

AL: Sitting down with Johnny Cash is certainly one of those moment I will never forget—when he walked in the room, it was like the moon walked in, something bigger and grander than a regular human being. He was not in great health when I was with him, so he needed to take breaks to focus and gather his strength, but he was totally present and sharp when he was speaking—it was clear that he wanted to give his all to the conversation.

AAJ: It seems that Cash is even more popular now than during his heyday. What would you attribute that to?

AL: The principles that he represents—the sense of justice and fairness, of empathy and refusal to judge the actions of others—are at a greater premium now than ever. The music that he made is truly timeless, so solidly built that it will never sound dated. And his look and style and image are so perfectly and unarguably cool that he will always be an icon.

AAJ: While you were writing this book, what was your biggest challenge?

AL: Fitting such an enormous story into a concise space. I had to prioritize and carve down what I wanted to tackle given the constraints of word count and deadline. I think that determining that there were a few themes—his social conscience, his faith, his relationship with June Carter—that should be taken out of the regular timeline and examined separately, as "sidebars" to the story, was the key to being able to do something that felt complete but not overwhelming.

AAJ: Did writing this book change the way you listen to his music?

AL: I suppose that it did—just connecting the dots between different eras of his career, seeing different interests surface, thinking more about his work as a whole rather than as separate songs or albums...I don't know that I had some huge revelation that changed my whole understanding of him, but I put them together a bit differently. Also, going to the house in Arkansas where he grew up was a huge moment. The town hasn't changed all that much since he lived there—a lot of the roads are still dirt, and the directions to his house still say "turn left at the cotton gin." To stand on the porch of that house, and still see nothing but cotton fields in all directions, no other house in sight, and to think about the vision and ambition required to see something different, something bigger, for yourself—to even imagine leaving the town, the state, and become an international figure—is really inspiring and powerful and fascinating. I could feel the book start to develop after I made that trip.

AAJ: In the past few years, you wrote several biographies about luminaries such as Leonard Cohen, Prince, Nina Simone, Jeff Buckley, Tupac and now Johnny Cash. What is the common thread between these artists whose music seems to have touched people's hearts and imagination?

AL: Huge question. Short answer is that they were all truly committed to their own visions, fearless in pursuing their creativity, leading rather than following their audience and its expectations. That is a list of really brilliant figures, and I've been fortunate to spend so much time thinking about them, but these are the very few who break boundaries and change lives.

AAJ: Were there any reactions from artists such as Cohen or Prince about your work while they were still alive?

AL: Prince was very positive about the magazine interviews I did with him (one of the few artists who ever sent me a thank-you note!), but I never heard anything from him about the book. I had a great moment with Leonard when I was asked to do a Q&A event with him when the "Popular Problems" album came out, and he paused in mid-interview to thank me for the "Hallelujah" book and say how much he appreciated it. Lucky my wife was there to witness or I wouldn't have believed it!

AAJ: Many of the artists that you have written about have passed away. We're losing so many key artists with each passing day. What are your thoughts about the inexorable march of time as it relates to people you have written about?

AL: I suppose it's inevitable that if you're writing about people who are truly legendary, they will likely be at an advanced stage of their career, or are already gone while still having an impact. Of course, that doesn't apply to Prince (or to Tupac or Buckley), but we do all know the hazards and track record of pop musicians who don't live long. I was braced for it when I was working with Gregg Allman, who of course was already in bad health, and Leonard was 80-plus years old, so those weren't shocking. But it's a tough phase that we're living through, watching so many of the idols we grew up with now reaching these advanced ages. We shouldn't forget how lucky we are that Dylan, McCartney, Jagger/Richards are still here—Chuck Berry and Fats Domino have both left us, but Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis manage to keep sticking around.

AAJ: Recently a documentary about Elvis was premiered on HBO "The Searcher." Please talk about your role in the making of this documentary.

AL: I was the writer for the film. I was brought in after lengthy discussions that brought Priscilla Presley and the estate together with HBO, and then Thom Zimny attached as the director—so I worked on the project for a couple of years, but it had already been in motion for a few years before that. I worked closely with Thom to outline and sketch out a plan for the two-part film, to determine interview subjects and write questions, and then to help shape the interview material into the story we wanted to tell.

AAJ: When did you first hear Elvis and what attracted to you to his music?

AL: Who knows when I first heard him—isn't he just there, always around us? I do remember vividly the day that he died, and the global outpouring of emotion and sense of his impact. He is one of the greatest singers ever, and he fused different music together in unprecedented ways that forever changed the world—and that was the story that has largely been lost to the world, and that we wanted to convey.

AAJ: What was the impetus for you to pursue the idea of an Elvis documentary?

AL: The initial thought is "what's left to say about Elvis?" But then that was quickly followed by the realization that, while there are some extraordinary books about him, no one had actually attempted to seriously look at his story with sound and picture—there are the concert/tour documentaries, but nothing that looked more broadly at his impact and his legacy.

AAJ: What was your primary aim in making of this film?

AL: From our first conversation, Thom and I talked about how the importance of Elvis is really lost to the world—that if you're below a certain age, you have no real relationship to Elvis. All that's left, for several generations now, is Elvis impersonators and the white jumpsuit and Elvis weddings in Las Vegas —the cartoon is the only thing that survives, and the sense of what he did musically and how he changed the world have just disappeared. It's like everyone knows his name but nobody knows why. So we really wanted to examine what was important about him, that whether you like his music or not, you could understand what his music had accomplished.

AAJ: What were some of the challenges involved in the making of this project?

AL: Working against those goofy images of Fat Elvis in Vegas. Any time we showed him in the jumpsuit, it just felt like it was impossible to see beyond that or to hear what he was doing. And the second half of the story—Elvis in the movies and Elvis in the 70s—was tough because we wanted to make clear the disappointments but also try to understand them, see what led to the decisions he made, and also not just feel like a long slide toward a terrible end that we already know is coming. The person who really made a huge difference, who provided some of the material that really locked in the points we were trying to make, was Tom Petty. He was the very last interview we did for the film, and of course it was one of the final interviews that he gave before his death. But he was so good and clear and specific and really brought home a few very central concepts for us—obviously the emotional impact of hearing from him greatly amplified after he passed, but the edit was already done, and he was just as prominent in the film, before that terrible news.

AAJ: What do you hope audiences will take away from this film?

AL: See above—I hope they can see past the contemporary image of Elvis as just a hillbilly who got lucky, or as a white guy who stole black music, and consider the actual artistry of his music. I hope they can understand that when he cut 'That's All Right Mama" at Sun Records, it wasn't just a fluke, but was the result of active study and pursuit of different music and styles in a very radical way.

AAJ: What the future holds for you when it comes to work?

AL: Trying to find the next big project—in conversations about a few potential books and documentaries, but we'll see what actually shakes out. Meantime, still doing three hours every weekday on SiriusXM satellite radio, and journalism when it's there to do.

< Previous

Chris May's Best Releases of 2018

Next >

Everything's OK

Comments

About Johnny Cash

Instrument: Guitar and vocals

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.