Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » When is a Jazz Festival (Not) a Jazz Festival?

When is a Jazz Festival (Not) a Jazz Festival?

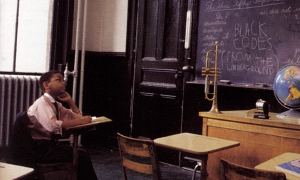

Courtesy Egghead06 and Skip Bolen

It's becoming almost pandemic for jazz festivals around the world to be challenged for deciding to broaden their programming into areas either peripherally related to jazz... or, in some cases, away from jazz entirely. Festivals like the near-iconic Montreux Jazz Festival, the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival and the Ottawa International Jazz Festiva have become easy targets for purists, who are loudly proclaiming "This isn't a jazz festival" because artists like Robert Plant's Band of Joy, Daniel Lanois' Black Dub, Seal and Deep Purple are showing up in the schedules. But the important questions are: why is this happening; and, when does a jazz festival stop being a jazz festival?

The answer to the second question is, of course, as contentious as the longstanding debate about what jazz is and—for some, more importantly—what it isn't. But examining the practicalities of managing a festival sheds some light on matters that many may not consider. And if it is fact that festivals are now being forced into a broader programming mindset than ever before, then looking at the schedules of those either in progress or looming on the horizon reveals plenty of food for thought.

Those who believe that a jazz festival stops being a jazz festival the minute it introduces any non-jazz into the program are advised to stop here. After all, there is, then, absolutely no justification for calling a festival like the OIJF a jazz festival, because it has Plant, Elvis Costello, Youssou N'Dour and Black Dub at its main stage this year. And, it's true, that this festival—which has long retained a reputation of purity long after larger festivals like Montreux bit the bullet—has significantly altered its main stage programming, with four of its eleven evenings bearing tenuous connection to jazz at best and three a little more closely tied, leaving only four shows that just about anyone could call jazz (though those who believe fusion doesn't count will be reduced by another two). But let's look at this festival and others, as a whole, before whitewashing them.

Fact: every festival is facing significant funding cuts—from both private and public sectors—the result of a global economy that often says, when times are tough, reduce funding to the arts. OIJF lost $80,000 in its bottom line last year, and like every jazz festival in the world, is also having to deal with the very real issue of demographics. Visit most jazz festivals and the preponderance of gray-hairs and no-hairs speaks to the challenge (and, largely, failure) of bringing a younger audience through the gates. And this isn't just a matter of ultimate survival, though jazz festivals that continue to appeal exclusively to the aging baby boomer population will most certainly go under within the next 10-15 years—if that. It's a matter of current economics. Government funding, for the most part, doesn't come with "no strings attached"; it's heavily tied to tourism, which means that if a jazz festival (or any festival) cannot show that it is bringing tourism dollars into its city, it'll have a hard time obtaining it. And while private sector funding is less directly tied to tourism, it is tied to profile, and how many people come to the festival and walk away with their logos in their heads. If audiences are shrinking, you can be sure that private sector funding will be reduced accordingly.

These are realities that each and every festival has to deal with, year-after-year. And some festivals—Kongsberg, Molde, Montreal, Montreux, New Orleans and Ottawa, to name just six—are all facing the same general problems, irrespective of country or continent.

One suggestion, from those who have a problem with broader programming, is to pare back ("get back to your roots") and become smaller, niche festivals, but in practical terms that simply isn't possible. You can't put the toothpaste back in the tube, they say, and festivals would have a near-impossible challenge of selling funders with the premise that "we're going to become a smaller, more focused festival, and appeal to a smaller, more select audience. Now, how about some money?" As is usually the case in a world driven by bottom lines, even artistic pursuits like festivals are expected to grow—to become bigger and better. Shrinking sends a bad message to just about everyone, and will do absolutely nothing to support the solicitation of funding, sponsorship and other critical forms of partnership that help festivals with everything from nailing down venues and getting instrument support to paying travel expenses to bring in artists from abroad.

Festivals must find new ways to attract that holy grail of attendance, the younger demographic, and they need to do so in increasing numbers. Sure, bands like Béla Fleck and the Flecktones will continue to bring in the jam band crowd, but it's megastars like Plant, Costello and Black Dub that are certain to bring capacity crowds of all ages to jazz festivals this summer. So, perhaps, it's also important to look at the acts festivals are bringing in to help bolster their bottom lines, and assess whether or not they are quality acts, acts that bring a certain amount of prestige, or are they acts that are about dollars and cents, and nothing more.

Certainly Plant, Costello and Black Dub are prestige acts—as are Paul Simon and Derek Trucks, both of whom are performing at Montreux this year. And, while it would be a stretch to call any of these acts jazz per se, digging a little beneath the surface reveals, at least, some tangential connections: Plant's roots in the blues are well-known; Costello has worked with jazz artists, including guitarist Bill Frisell on their Deep Dead Blue (Warner Bros., 1995) EP—even singing a Charles Mingus tune; Black Dub's drummer is Brian Blade, certainly no stranger to the jazz world; Paul Simon has collaborated with many jazzers on albums and on tour, including Steve Gadd and the late Michael Brecker; and, while Trucks fits more squarely in jam band space, he has been known to put his slide to work to the occasional jazz tune—his first album, The Derek Trucks Band (Landslide, 1997), released when he was just 17, containing not one, but two tunes by John Coltrane, and a cover of Miles Davis' "So What" to boot. The same, sadly, cannot be said of Deep Purple, Ricky Martin, Liza Minelli and Arcade Fire, all performing this year at Montreux.

It's also of no small importance that if these larger scale shows bring in the crowds that festivals hope, they will absolutely help to fund jazz acts performing in smaller venues—and to more realistically sized audiences—such as Atomic, Christian McBride, Vijay Iyer and Kenny Wheeler / Myra Melford in Ottawa; and Ahmad Jamal, Anat Cohen and Terence Blanchard in New Orleans. Montreux is a little different in that, for the most part, it operates in only two large venues, which brings its programming into more question, as it doesn't really have any small venues for lesser-known jazz artists. And that means its decision to book acts, in previous years, like Motorhead and Alice Cooper far more questionable. Whether or not Montreux is, in truth, a jazz festival may be a good question, but how about New Orleans and Ottawa?

One good yardstick to decide whether or not a jazz festival is a jazz festival is the answer to a single question: can you attend the festival for its entire run, ignore the non-jazz programming, and still be immersed in a broad cross-section of jazz each and every day... even facing difficult choices about what you decide to see? In the case of Montreux, the question is, sadly, a resounding no.

But if you're already attending the New Orleans festival, or are making plans for Ottawa, the answer is an absolute and unequivocal yes. Sure, those who only think of OIJF for its main stage in Confederation Park will bemoan the dearth of previous year mainstreamers like Dave Brubeck, Latin artist like Paquito D'Rivera, or specialty projects like Jimmy Cobb's Kind of Blue tribute band. But move into one of the festival's two indoor venues, the tented OLG stage, or the new Canal Stage for the early evening Great Canadian Jazz series, and you've 11 days and 83 acts that are undeniably well within the jazz sphere. New Orleans' programming is almost exponentially larger, with 12 stages, and shows beginning in the late morning, and running through to the early evening. Is it really so offensive to go to a jazz festival that is programming some peripherally related—or even totally unrelated—acts, when you've got so much "real" jazz from which to choose?

Here's the reality check. There are really only two choices for most jazz festivals around the world: insist that festivals retain their absolute purity, and watch them run themselves into the ground in short order; or accept that a broader purview is necessary, in order to exist, as long as that purview isn't at the expense of a primary jazz focus. Me? I'll be first in line for Robert Plant and Black Dub, but I'll also be lining up for Atomic, The Thing, Joshua Redman and Brad Mehldau, Kurt Elling and Jonas Kullhammar. And I'll be all the richer for it. Jazz, after all, has always been about inclusion and cross-pollination, rather than exclusion and a glass box mentality, hasn't it?

Comments

Tags

Opinion

John Kelman

United States

Bill Frisell

Charles Mingus

Brian Blade

Steve Gadd

Michael Brecker

John Coltrane

Miles Davis

Atomic

Christian McBride

Vijay Iyer

Kenny Wheeler

Myra Melford

Ahmad Jamal

Anat Cohen

Terence Blanchard

Dave Brubeck

Paquito D'Rivera

Jimmy Cobb

The Thing

Joshua Redman

brad mehldau

Kurt Elling

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.