Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Thomas Stronen: The Tin Drum

Thomas Stronen: The Tin Drum

This is what they say in Japanese music: if the next hit won't change the music, then don't hit it. It is like the opposite of jazz in a way, where there's too much information all the time.

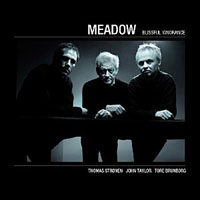

Strønen is also one-half of Humcrush which, since coming together in the early part of the new millennium with Supersilent keyboardist Ståle Storløkken, has taken its own path down the road of in-the-moment composition. Its third album, Ha! (Rune Grammon, 2011), has just recently been released, and documents the duo's ongoing collaboration with experimental Norwegian singer Sidsel Endresen. Blissful Ignorance (Hecca/Edition, 2010) documents the first meeting of the lyrical Meadow—a trio with Strønen , Norwegian saxophonist Tore Brunborg and British pianist John Taylor—while The woods are not what they seem (BJK-Music, 2010) represents another first-encounter of sorts, by the newly formed Needlepoint, a trio with bassist Nikolai H. Eilertsen and guitarist Bjørn Klakegg.

With so many concurrent projects, there's an unmistakable thread that runs through them all: Strønen's remarkable ear for color and texture, and an approach that values the collective over the individual.

All About Jazz: Where is your music coming from?

All About Jazz: Where is your music coming from?Thomas Strønen: If I look back now, I don't know why I started playing drums at all. I am half-German—my mother is German—and we were in Germany visiting when we passed a shop, where I saw this little drum in the window, like the one in the film The Tin Drum (1979). I was five years old and I just stopped in front of the window and said, "I need that drum." My mother didn't even think about it. This was probably the only time I've cried for hours, so at the end my parents gave after and bought me the drum. On that day my drum replaced my teddy bear; I had it with me in bed, I had it hanging round my neck while I ate and while I was brushing my teeth. I had it with me practically everywhere and I got an extremely big kick out of playing it. Obviously I was doing all the other stuff kids do, like playing football, but drumming was definitely The Thing.

AAJ: Were you active musically in school?

TS: Yes, I was very active. At age nine, I started in a school band and three years later I started a rock band together with three friends. We began to write material and lyrics quite early. We were ten or eleven when I wrote my first lyrics (I can still remember them) and wrote songs just by trying them out on piano and guitar. We were playing a kind of soft rock. We thought that we were pretty heavy at that time, but in fact it was really soft.

By chance, a local composer and trumpeter called Terje Johannesen, employed as a kind of social worker meant to encourage and promote young bands and musicians, helped us out. He was also the leader (and composer) of a semi-big band called Slagen Band (a band that included many great young musicians, like Martin and Lars Horntveth of Jaga Jazzist, and Vidar Johansen, at different times). The band was a bit similar to Oslo 13, which was Jon Balke's first project with a larger ensemble before starting the Magnetic North Orchestra. At age 14 (and with no references to improvised music), I joined the band. Most of the musicians were in their thirties and forties, so the learning curve was rather steep.

The guys in the band started giving me tons of records and took me to concerts; they sort of raised me musically. I played in that band for six years and that's when I started improvising. I didn't know anything about the American jazz tradition at that time; I only knew European and Norwegian jazz-influenced music. I never got to know (or like) the fusion jazz-rock scene because I went straight for a more open kind of music—ECM Records and that stuff.

When I went to high school, I decided to study to become a marine biologist, studying math, chemistry and physics and stuff like that, because I thought that was the right direction. During high school, music took most of my focus, and so I changed my mind and went to the Trondheim Jazz Academy to study jazz and composition for six years. At this stage I discovered the American jazz tradition through lots of recordings and concerts.

AAJ: What are your main influences?

AAJ: What are your main influences?TS: Because of my background, I was never concerned about different genres or if something was "real" jazz or not. I had periods when I was listening to the different periods of Miles Davis' music, John Coltrane and American music in general. Later, I got very influenced by Japanese music, electronic music, classical music and choral music. I got very interested in Eastern music in general, like Pakistani and Indian music. I also discovered classical music, fell in love with Glenn Gould's interpretations of Bach, and various string quartets.

Looking back, it's obvious I was living in a bubble while studying in Trondheim. I got up really early, was at school at seven in the morning, practicing and listening to records. That, and going to concerts, was all I did. I realize that I was a very structured student all those years, as if I knew that, after that, a totally new life would begin.

I was very lucky at crucial points in my life, in terms of meeting people that would influence and inspire me. At the jazz academy I met [trumpeter] Arve Henriksen, and shortly after, I met Iain Ballamy, and we started working together. You know, I met people with open minds and I started being part of their playing.

Suddenly, you find yourself onstage, realizing that music moves you and takes all your energy. The only choice was to take it seriously. I guess I've always been focused on playing my music, the music I wanted to play. I've never been a drummer for hire, just playing a drum score. So it was pretty clear to me, quite early, that I needed to find musicians who fit my way of thinking and playing, and that I was more of a colorist and soloist as a drummer. I like to be in the center, where everything is happening, I like to have the possibility of changing direction, not just be polite, sit aside and follow up the soloist. I need to be in it.

AAJ: How did you come to combine drums with electronics?

TS: Well, that's quite interesting, because it wasn't on purpose. It happened when I met Arve Henriksen; it was his fault, actually. I was sitting in the studio practicing from morning till night, and at some point I got extremely tired of the sound of my drums and the cymbals. They just annoyed me a lot, and I told Arve that I was bored with the sound. He suggested I buy a sampler to play along with. I had never seen a drummer work on samplers at all, so I asked him what should I buy, and he suggested the sampler that he had. I bought it and started working on it. I started recording rudiments in different time signatures and tried improvising on that, worked on fully formed rhythms and grooves, and slowly adding a few effects and finding out how to use them.

AAJ: There's a certain rhythm in your movements. Are the electronics an addition or an extension to your drums?

TS: In the beginning I was terrified about moving my hands away from the drums. It was very challenging and I realized that I had to practice playing and doing the tunings. In the beginning, it sounded horrible; it was either one thing or the other. It was like learning a new instrument, in a way, and then it just developed. Now it is a natural part of me behind the drums. These days it isn't any different from moving to a cymbal or a drum. It is a whole.

AAJ: Last year at Enjoy Jazz, [trumpeter] Nils Petter Molvaer said, during an interview that took place just before the show you did together, that everything in the show was going to be improvised. Are you actually experimenting together along a specific conceptual track or does it just happen?

TS: Improvisation is like a language you have the words for, and you just have to put them in the right order to make meaning out of them. Sometimes, when the communication is good, you listen and you talk and it all goes very naturally, and the conversation may take a different turn because of the "things that have been said" or the chemistry; sometimes you deliberately take a turn to make things more interesting. Iain and I have played together since 1997 and we still rehearse a lot. We meet several times a year and we rehearse one week at a time, ten hours a day. We talk, we play and we agree upon the parameters of our conversation.

AAJ: Do you have an ideal audience?

TS: I can't really say. I'm always surprised that people like the music I play, because I know that it is challenging. It is different in every country and every culture. I am excited about tonight [performing with Food at Romania's Garana Jazz Festival 2011] because I know that it is going to be a big crowd and the music that is presented before us [Hiromi Uehara Trio] will be very different. We're not reaching out to the audience that way. We are inviting them, and they have to come along of their own free will. I was very surprised the other day, in London, when a woman in her late fifties came to me after a show at a quite conservative party and told me that she had never experienced such a thing in her whole life. She said that she had closed her eyes and was in a movie where she was doing her own visuals. She opened up and she just let the music come to her. There's nothing to understand about my music. You just have to take down your guard and let it speak to you.

AAJ: Do you think that there's a common Nordic jazz heritage? If so, what would its characteristics be?

AAJ: Do you think that there's a common Nordic jazz heritage? If so, what would its characteristics be?TS: Nordic Jazz was something that started in the late sixties. Today what is called Nordic Jazz is not disappearing, but it is developing into something else. These days, Nordic musicians want to belong to a larger category; they don't want to be restricted to that geographic denomination anymore. I think the heritage is about openness. Jon Christensen, Arild Andersen, Terje Rypdal, Jan Garbarek and a few others brought in a wide spectrum of genres, from classical music, from rock, and from ethnic sources Garbarek, for example, was into John Coltrane and Gato Barbieri, but he did it in a different way and added new flavors.

AAJ: Where do you see the role of drums and percussion in general today? Has anything changed there in the last 30 years?

TS: It is quite difficult to answer, being in the middle of it. But the roles have definitely changed. The drummer is not there to merely keep the rhythm anymore. They've moved from backing up soloists into the center of the music-making, and in many bands the drummers has a totally free role, while other guys are keeping the time. Compared to 30 years ago, drumming has become more about color and texture, but the actual playing hasn't changed that much. We still listen to Roy Haynes and think, "God, how can you play that funky," but the role of the drummer has definitely changed. Drummers plays in different settings, with DJs or samplers, and there is a lot of mixture between scenes, like classical meeting metal.

AAJ: You are involved in quite a few parallel projects. Would you like to develop their significance? What are the points of convergence, what differentiates them? What side of you do they each represent?

AAJ: You are involved in quite a few parallel projects. Would you like to develop their significance? What are the points of convergence, what differentiates them? What side of you do they each represent? TS: I try to not play into too many bands. I feel that instead of using all the different aspects of my musicianship in one band, I can sort of use some sides and go really deep in a certain direction. For example, Food is connected to my listening to a lot of Japanese music, where I use space and texture, trying not to play all the time, trying to play open, trying to believe that one hit will change the next movement. This is what they say in Japanese music: if the next hit won't change the music, then don't hit it. It is like the opposite of jazz in a way, where there's too much information all the time.

So this band is very much about daring to be open and daring to develop things all the time. You can have one tune lasting for fifteen minutes if it's interesting enough. It has a lot to do with texture and about being one big sound. There will be sounds you will identify, and others you won't be able to tell where they are coming from. Even if we improvise we like to have a strong shape, a strong form so that you have the feeling that it is composed, even if it is not.

It is a very well-defined music compared to Humcrush, where we are taking more risks, and which is a lot quicker. Humcrush is like you put something into a blender, and everything goes faster and comes out spattering as something else. Here you can have five tunes within five minutes, totally different things, even if we sometimes stretch out, it can be much more extreme. We can have one gig being extremely loud all the time with no dynamics, but working on other parameters like sounds, shifts, energies or beats. It is more outrageous; there is more power in it. It is probably hard in one way to listen to, and it is really about having big ears and reacting to the other guy—or woman, when we play with Sidsel Endresen, who's featured on our latest record.

Meadow, where I play together with [pianist] John Taylor and [saxophonist] Tore Brunborg, is more of a chamber group, into colors, extremely into detail and dynamics. We work a lot on the dynamics, from silent to even more silent; playing really softly and compressed

And sometimes I just play solo with Pohlitz, which began as an exercise when I started playing with samples. I just play percussion, I don't play drums with Pohlitz, I just sit on the floor and there are sounds, bells and gongs all around me.

Food, with Special Guest Christian Fennesz

From left: Fennesz, Iain Ballamy, Thomas Strønen

AAJ: Have you ever been to Bali?

TS: No, I haven't been to Bali. Actually I started checking out Gamelan music after I did the solo record, Pohlitz (Rune Grammofon, 2006) record. In many reviews, journalists referred to gamelan music, while I knew very little about it. I was more into Steve Reich, John Cage and Arne Nordheim, and then it was more like building up things from the beginning, patching samples and creating a small world of sound and also letting the audience be with me along the whole trip. In the beginning, you hear the absolute sounds, before I start putting it together and making small compositions out of them.

After I did that record, I needed to do something else, so I started to write for string quartets; on the compositional side, that's what I spend most of my time on these days.

Selected Discography

Humcrush/Sidsel Endresen, Ha! (Rune Grammofon, 2011)

Food, Quiet Inlet (ECM, 2010)

Needlepoint, The woods are not what they seem (BJK-Music, 2010)

Meadow, Blissful Ignorance (Hecca/Edition, 2010)

Various Artists, Money Will Ruin Everything 2 (Rune Grammofon, 2009)

Trinity, Breaking the Mold (Clean Feed Records, 2009)

Humcrush, Rest At Worlds End (Rune Grammofon, 2008)

Food, Molecular Gastronomy (Rune Grammofon, 2008)

Maria Kannegaard Trio, Camel Walk (Jazzland, 2008)

Humcrush, Hornswoggle (Rune Grammofon, 2006)

Mats Eilertsen, Flux (AIM, 2006)

Various Artists, Until Human Voices Wake Us And We Drown (Rune Grammofon, 2006)

Thomas Strønen, Pohlitz (Rune Grammofon, 2006)

Food, Last Supper (Rune Grammofon, 2005)

Thomas Strønen, Parish (ECM, 2005)

Thomas Strønen/Ståle Storløkken, Humcrush (Rune Grammofon, 2004)

Parish, Rica (Challenge, 2004)

Photo Credits

All Photos: Richard Wayne

< Previous

Cartography

Comments

Tags

Thomas Stronen

Interview

Adriana Carcu

Food

Iain Ballamy

Arve Henriksen

Mats Eilertsen

Humcrush

Supersilent

Sidsel Endresen

Tore Brunborg

John Taylor

lars horntveth

Jaga Jazzist

Jon Balke

Miles Davis

John Coltrane

Glen Gould

Enjoy Jazz

Nils Petter Molvaer

Jon Christensen

Arild Andersen

Terje Rypdal

Jan Garbarek

Roy Haynes

Steve Reich

John Cage

Arne Nordheim

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.