Home » Jazz Articles » Talkin' Blues » Talkin' Blues with the Groovemaster, Jerry Jemmott

Talkin' Blues with the Groovemaster, Jerry Jemmott

Jemmott was with singer Aretha Franklin, the Queen of Soul herself, when she conquered San Francisco's hippie community at the Fillmore West in March of 1971. The album, drawn from this series of concerts (with a surprise appearance by singer Ray Charles), earned her a gold record, and was something she would later refer to as a highlight of her career.

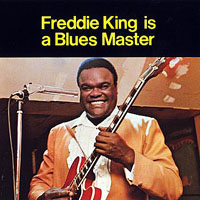

Jerry Jemmott's blues credits are truly remarkable: in addition to B.B. King, Freddie King, Mike Bloomfield, Duane Allman, Otis Rush, Johnny Winter, Warren Haynes, Derek Trucks, there's his legendary association with Cornell Dupree, Bernard Purdie, and King Curtis. In my last column, Jimmy Herring had this to say about him: "He's a genius, there's just nobody like him. He's the sound that defined an entire generation. I love Jerry Jemmott, it doesn't get any better than that."

Another of his seminal achievements, which will no doubt be watched by generations yet unborn, was his collaboration with Jaco Pastorius on the instructional video Modern Electric Bass (1985). Even beyond its instructional value, because it was done so close to Pastorius' death on September 21, 1987, it provides an invaluable insight into this extraordinary musician and composer. Pastorius had this to say about Jerry Jemmott: "He was my idol. That stuttering kind of bass line, bouncing all around the beat but keeping it right in the groove—well, they don't call Jerry the Groovemaster for nothing. He's the best."

In this extensive interview Jerry Jemmott speaks about all this, as well as his wide ranging session work for Atlantic Records, and his current gig with blues/rock legend Gregg Allman.

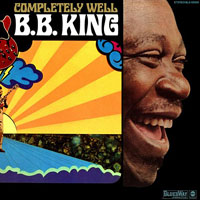

B.B. King

All About Jazz: I want to ask first about the sessions with B.B. King for "The Thrill is Gone." When you guys finished and heard the playback, was it just another song that day, or did you have the feeling that this could become something momentous?

Jerry Jemmott: You have to look at it from our perspective. We came together to revolutionize his music, so it was with great intent that we set forth. We were thinking in terms of taking things apart and reconstructing the music so to speak. But it happened naturally through the selection of the people involved, starting with the contractor, Herb Lovelle. Earlier in the '60s he had worked with the same producer for Bob Dylan to make his music more accessible.

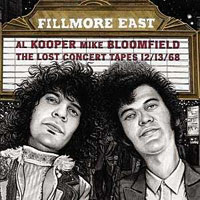

That's part of the reason you know Bob Dylan today, because of Herb and his partner, whose name escapes me right now, but they had a reputation around New York for being able to turn peoples' music around. So, for that reason, they called him to do the B.B. King sessions. He played the drums, Paul Harris was on keyboards, and Al Kooper was there—so we knew we were there for a reason. They had about 20 minutes of a live party album, but it wasn't enough for a full album, so they had the idea of coming into the studio.

In the studio you can construct things and make a memorable recording. So if you do something, you're thinking, let's make this the definitive version of the song. That's always my approach when I go into the studio. As it turned out, later I learned from B.B. that he'd been working on "The Thrill is Gone" going back six years prior to this session. He'd performed it live a few times, but he could never quite get it the way he wanted it.

He was comfortable letting us do our thing because the previous album had been successful and the song "Why I Sing the Blues" had gotten a lot of air play, so he was happy with that. So the next time we came together in the studio he brought in "The Thrill is Gone" and said, "Let's see what we can do with this."

He was comfortable letting us do our thing because the previous album had been successful and the song "Why I Sing the Blues" had gotten a lot of air play, so he was happy with that. So the next time we came together in the studio he brought in "The Thrill is Gone" and said, "Let's see what we can do with this." It was Herb's idea to put strings on it.

AAJ: Sometimes those string things can really transform a song. Like James Brown's "It's a Man's World," I've heard a version without the strings, and man, the strings really did the trick.

JJ: Oh for sure, without a doubt! Strings are beautiful.

AAJ: Were the strings on "The Thrill is Gone" live with you guys?

JJ: No, that was Herbie Lovelle's idea, and Bert de Coteaux did the arrangement after the fact. Bert is great.

AAJ: Oh man, those cellos are wild.

JJ: Yeah, what they would do in those days is pick up the rhythm parts and duplicate and amplify them. Then they would take the rhythm section down in the mix and you would hear the strings.

AAJ: It's so cool, the way he did it, it's like a spontaneous dialog between you and the cellos.

JJ: Bert was phenomenal, he was able to pick up on that, and on the lines that Hugh McCracken was playing. That's their technique, it's called sweetening. Sometimes it's accentuating or it can be a call and response.

AAJ: Have you seen B.B. out, or on video lately? A few years back at the Crossroads Festival, even in his 80s, his voice was just unbelievable.

JJ: I haven't seen him recently, but I started going out to see him in the 1980s because I hadn't seen him since the '60s. It had been almost a 15 year gap from the time that we recorded "The Thrill is Gone," and he was so warm and affectionate when he greeted me. I was embarrassed because of all the praise and appreciation he showered on me for my work when he introduced me to the musicians in his band—I think that was in Newark, New Jersey.

I've seen him a few times after that, I've kept up with him until—it was 19...no 2000, [laughing] I feel like Champion Jack Dupree. He'd be talking about the 1800s and then say, "No, I mean the 1900s!" And we all would crack up, we were in our 20s, so he was an old man to us, talking about the 1800s, when he was a boy.

So anyway, I saw him last in 2006 and he sounded great, and I hear from people that he's dropped a lot of weight and he's feeling good. The fact that he's singing great, I'm not surprised.

King Curtis, Jerry Wexler

King Curtis, Jerry Wexler AAJ: When you met King Curtis, that was in the mid-'60s when he was really riding high. He'd opened for the Beatles when they played Shea Stadium.

JJ: Yes I met him shortly after that as I recall. Other people have told me that he'd seen me play years prior to that, but I hadn't had any contact with him. I used to play every little nook and cranny club around New York when I started out. Court Basie's, the Barron Club, Smalls up in Harlem—so he was familiar with my playing back then, but I didn't actually meet him until 1967.

AAJ: People from my generation tend to think of him in terms of R&B and rock 'n' roll, but I'm guessing his tastes and skills went much deeper, is that right?

JJ: Yes his roots went deep into the jazz circle, he'd played with Lionel Hampton, you know, swing and straight ahead jazz. He knew what to play for each style, so when you think of rhythm and blues, it's blues and rhythm. So he could take his jazz improvisational skills and move things around to create these unique sounds. We were coming out of New York and thought we were sophisticated; we brought things like the Latin influence, but he brought influences from Chicago, New Orleans, and the South.

Even musicians from the West, you know when you think about it, it all came out of this place (Mississippi) and spread out everywhere.

AAJ: I've heard that King Curtis could also play guitar, did you ever see him play guitar?

JJ: Oh yeah! I can't recall him recording on guitar, but sure, he'd show someone how to play a part, or play an idea. He'd write songs on the guitar and then transcribe it for the saxophone.

AAJ: And man, he knew how to spot a great guitarist.

JJ: That's for sure!

AAJ: Did you ever hear that he had Jimi Hendrix in his band for a while, back when he was still known as Jimi James?

JJ: Sure, that's when Jimi came to New York. That's when Chuck Rainey was in the band. I wasn't in the band then, but Cornell always used to talk about Jimi being in the band—so that was at the beginning, and that was quite a band.

Jimi had been with the Isley Brothers before that. It's funny how musicians can be floundering here, and then go to Europe with a more receptive audience and really turn things around.

AAJ: It's interesting, I always thought you, King Curtis, Cornell Dupree, and Bernard Purdie transcended racial barriers, and you connected a lot of white Southern players with R&B. When I was growing up, most black kids weren't interested in The Beatles or Jimi Hendrix and that kind of thing, but among white kids soul music and R&B was also very popular. Still, they remained still two very distinct worlds.

But you guys connected with a rock audience in a different way, you kind of lived in two worlds. I guess when you're out with Gregg Allman on the road you still feel that special connection you guys forged.

JJ: I certainly do, and that's all part of the King Curtis legacy. He was the one who was proactive and recording their material. Before him it was the white artists who recorded the black artists' music and would have hits with it. A lot of times the black artist's music would be shelved because all of a sudden a white artist's cover version would take over the airwaves. Historically that's the way it came down.

[Laughing] King Curtis would take music that white artists had done and cover it. Looking at it in retrospect, he wasn't the first to do it, but he did it a lot! You know, coming from the jazz world, it was common for jazz musicians to take Broadway show music, which was often the popular music of the day, and jazz it up. He would just do it on music like "Whole Lotta Love!"

AAJ: It interesting, I heard an older interview with Eric Clapton and he was asked what his favorite recording studio experience was, and he said it was with King Curtis doing a song called "Teasin' " when he was working with Delaney and Bonnie.

JJ: That's beautiful.

AAJ: So how about you, what session would it be?

JJ: That's difficult, because I would like to pick different periods in my life. As you get older, the glitter and the awe kind of wears off, and you feel like this is business. So let's say when I was young and worked with Nina Simone, and later sessions with her, those were magical.

AAJ: Another interesting thing about King Curtis is his role at Atlantic Records. Could you could share something about how he and Jerry Wexler worked together and influenced each other creatively?

JJ: He had a talent for bringing artists into the studio and surrounding them with the right musicians to achieve a goal. He had a knack for putting the right people together, he would often cross country, rock and rhythm & blues.

He and Jerry worked well together, and they were making the right phone calls. In the beginning King Curtis would call me, and then Jerry began to call me directly. Jerry was also interested in the overall production in a supervisory capacity.

AAJ: He was also a creative guy too, right? Not just about budgets and things?

JJ: Definitely. He also understood that by making the right calls, the less he would need to be involved. He could sit back and give directions, and he knew how to communicate with people. He allowed us to do our thing, and trusted us to come in and do the right thing.

He might have an idea and then ask one of us to interpret it. He and King Curtis were both very good at communicating the ideas they wanted us to interpret. They were "people people."

King Curtis was more musical and could explain what he wanted you to do. Jerry might mention another style, or occasionally another artist to convey what he wanted. He might get the feeling and start dancing or doing stuff.

AAJ: Did you start out with King Curtis in his band, or in the studio?

JJ: I didn't want to play with King Curtis's band live after he recorded "Memphis Soul Stew" without me. He had promised me studio work to get me to join his band. Becoming a studio musician was my focus and goal. The seed was planted in my head by a trumpet player named Richard Dugan, he was a bit older and had hung out with a bunch of the studio cats like Snooky Young and Ernie Royal in the early '60s.

So the promise of studio work is how King Curtis lured me out onto the limb and into touring. This meant I had to give up my day job, and I had just started a family.

So when he recorded that without me, I was pissed. I was only 20 years old. He explained that he wasn't the producer on that session and hadn't made the calls. But I left the band and joined Lionel Hampton's band. [Laughing] I ended up having some differences with Lionel along the way and he fired me. So I ended up back in New York without a job, and King Curtis called and said, "Look, you don't have to be in the band, just make my records." So he started calling me for his records and for other peoples' records.

Muscle Shoals

Muscle Shoals AAJ: Jerry Wexler said that he preferred what he called the "Southern Style" of recording, working without sheet music and letting the musicians work it out on the spot. He said it was more creative, but also cheaper if you don't have someone running around altering charts and sheet music—that costs time and money.

JJ: [Laughing] The Southern Style was when people would come in and play all day for half the money! That's what he was really talking about, bless his soul.

AAJ: Was Jerry the guy who got you down to Muscle Shoals?

JJ: Yes. I made four trips for him. I took over for Tommy Cogbill. I guess he got the idea when the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section came up to New York and I recorded with them then—that was the first session I recorded with Aretha Franklin.

Initially I was there as an observer. King Curtis called me and asked me to come in, and said, "Bring your bass, you might play, you might not. But I want you there." So I sat around in the morning from ten to one while they were working on this song. They were going over and over on it, and it just wasn't happening. So around two Jerry Wexler told me to go in and see what I could do.

I've always had a knack for knowing how music should sound. I get an actual physical reaction when music doesn't feel right to me. I had sat there in agony, and kept asking, "Don't you hear that?" So when I finally got a chance to play, it caused everyone else except Aretha to change their part. They had been approaching it as playing against Aretha to create a contrast, and I began playing with her.

And that's when we recorded, "Think." On the third take it was done. So after that I stayed on for the sessions and Tommy switched to guitar. That's when I first played with Roger Hawkins, Jimmy Johnson and Spooner Oldham.

So after that Jerry called me and asked me to go down South to Muscle Shoals to play with them, as opposed to having them come up here. So we worked it out in terms of what I was going to get paid for multiple sessions as opposed to the regular rate.

AAJ: Muscle Shoals is in Alabama, but near the Tennessee line, kind of between Nashville and Memphis. I've read stories of Aretha's husband drinking with the good ole boys at Muscle Shoals and things got kind of tense. So I was curious, what was your initial impression of Muscle Shoals? It seems kind of strange, they had all these good ole boys and these R&B artists like Wilson Pickett coming through, yet it worked so well.

JJ: That's true, I read about that with Aretha, and after that, she didn't go there, they went to New York or Miami to record with her.

When I got there in 1968 it was cool, in the studio everyone was minding their Ps & Qs and was on their best behavior.

Duane Allman

AAJ: You and Duane Allman were friends, and about the same age, so I was hoping you could share a bit of your first impressions. Dickey Betts once said that Duane Allman had a personality a lot like one of his heroes—Muhammad Ali. He seemed to have so much confidence, there's a great quote from Duane, "It's a rat race out there, but my rat's winning!"

JJ: [Laughing] Right, we were only about six months apart. What Dickey said is a good description of Duane, he was a fighter. He was a strong personality, and his look back then made him stand out, a long-haired blond hippie—that was new back then, it was the '60s and the beginning of the Flower Power thing.

From left: Duane Allman, Jerry Wexler, Jerry Jemmott

From left: Duane Allman, Jerry Wexler, Jerry Jemmott Of course, he was from the South, and he was very soulful—that's the thing I remember most of all about him. He had a lot of compassion for music and for people, and he was strong in that sense. That Muhammad Ali reference is really cool, because he fits that, he was strong, really strong.

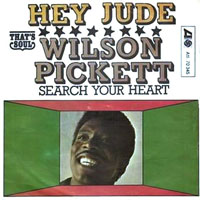

And his brother Gregg says the same thing about him. Of course my connection with him was primarily about the music, and his passion about the music was really strong, he went for it. I remember Wilson Pickett started calling him Skyman, and later that somehow became Skydog. He was cool people, he was great.

AAJ: I read that he was renting a cabin down around Muscle Shoals, how about you?

JJ: Oh no, we stayed at the Downtowner when we worked together there. The funny thing is, we always met up at the airport coming in from Atlanta, so I'd always page him.

The last time we went down there, we both had misgivings about going down there, and we didn't want to go down there anymore.

AAJ: That was a different time for sure. Remember that Peter Fonda movie Easy Rider (1969), you know the rednecks in a pickup shoot a hippie at the end. Rednecks used to say they hated the movie, but at least it had a happy ending.

So here's Duane with shoulder length blond hair, and blacks and whites didn't hang together in the South back in the day—so how was it, were you guys able to hang out outside of the studio?

JJ: Well, we'd go from the airport by cab to the Downtowner, and we'd take a cab to the studio, and a cab back to the Downtowner. So we'd hang out there and jam, and do the same thing the next day. So we really didn't have much contact with the local town.

You know in 1967 and 1968 I had a huge Afro. I was the first kid in my school to have an Afro [laughing]. My barber died, I didn't know I was starting a trend, I couldn't get a haircut because my barber died. From 1961 on, I started letting my hair grow.

AAJ: When you guys worked with Aretha, were you and Duane with her in the studio, or where things dubbed in later?

JJ: Well he came in later. My first sessions with Aretha were just with the cats from Muscle Shoals, and then with the next series of sessions, somewhere along the line he came aboard.

AAJ: So she wasn't necessarily in the studio with Duane?

JJ: Oh yeah. He would have been there, all those sessions were done live. By live, I mean everybody who was going to be there on the session was in there at the same time. Cissy was in there with the Sweet Inspirations ready to jump on the background vocals as soon as we finished. The horns would come on later. It would be the rhythm section, and while we were playing they'd be figuring out their parts. Most of my sessions, like with B.B. King, were the same way. A lot of sessions were done live in those days.

AAJ: It's really kind of fascinating, you know Wilson Pickett's recording of "Hey Jude" is what put Duane on the map in the music world, and you were there with him for that. And it kind of went full-circle you were also there with him for the Herbie Mann sessions for Push Push, his first and only jazz outing, and the last full album he recorded. So you were there at the beginning and at the end.

AAJ: It's really kind of fascinating, you know Wilson Pickett's recording of "Hey Jude" is what put Duane on the map in the music world, and you were there with him for that. And it kind of went full-circle you were also there with him for the Herbie Mann sessions for Push Push, his first and only jazz outing, and the last full album he recorded. So you were there at the beginning and at the end. JJ: That's true. And I remember talking with him after our last session together before the started his band, and I told him, "I'm not gonna do this anymore, I'm gonna stay in New York and do jingles and films." You know, there and in the studios in New York, I wasn't just playing. Without charts I was doing a lot of arranging and not getting any credit or pay for it—so I was tired, really burnt out. At that point I was only 22 or 23.

I remember Duane felt the same way, and he told me he was going home to start a band with his brother. And that's what he did, and I didn't see him again until the sessions with Herbie.

It's ironic, forty years later Duane's brother Gregg tells me a story that when he was in California he brother called him and said he was going to get a band together, so come back home, I've got this great bassist with these long fingers.

So when Gregg shows up, he asked Duane, "So where's the bassist with the long fingers?" and Duane told him, "He's up in New York, he's making too much money doing commercials and stuff."

Gregg told me Duane would tell him all kinds of stuff as they were coming up. They were only a year apart, but he played that older brother thing to the max with Gregg. That was just one of many things like that; Duane always had a plan, even to keep Gregg out of the Army.

But that was the thing about Duane, he had direction and he had conviction, and if he told you something, he could make you believe it.

AAJ: Of course by the time of those Herbie Mann sessions you'd played with all kinds of jazz legends, so I imagine Duane was relieved to see you and Bernard Purdie in the studio. Do you think that was intimidating for him in that setting?

JJ: Well we didn't call it crossover back then, but we'd been called in to basically crossover— and, like I said before, as musicians we weren't thinking it terms of labels, we were constantly crossing over. Now I call it downloading, you know, whatever you need to create the right fit is what you pull down.

So Duane was cool like that, playing different types of music, I don't think he was intimidated. They wanted lead guitar and slide, so that's what he did. He did his thing.

AAJ: How did you get the news about Duane?

JJ: When he had the accident I was in Atlanta going to a gig with Roberta Flack, and we were listening to the radio when a news bulletin came on.

Gregg told me that Duane never liked to ride with the pack—he had two speeds, park and 60, and I knew back then that he liked to drive fast, but that news hit me really hard.

Touring with Aretha Franklin

AAJ: Another really sad thing was the tragic murder of King Curtis in the summer of 1971. On Aretha Live at Fillmore West (Atlantic, 1971) you hear her say how much she enjoys playing with you, Bernard Purdie, Cornell Durpree, and King Curtis, and how she's looking forward to years of working together with you guys. That was just such a magical combination.

JJ: It really was. And King Curtis put that together. Like I said before, I'd told him, "I didn't want to go on the road anymore—so don't call me to go on the road." So I told him no, the first time he asked. We were in the studio recording something of his, and I remember him telling me about the project, what he had in mind, and who would be in the band.

Eventually I relented. We had a special connection, there were a lot of guys out there, but he knew what he wanted—and he wanted me. He knew my spontaneous interplay with Cornell, Purdie, Billy Preston and the singers was what this band needed. So he had that vision, and he sold the idea to Jerry Wexler.

He and Jerry saw that by playing to the hippies, they could open up a new market, and this band was the vehicle to get it there.

AAJ: You know what I thought was really cool about that idea, at that time there were lots of black female singers in sequined gowns standing out front. But now we also got to experience Aretha as a musician in the band. She had great feel on the piano and seemed to really enjoy being part of the band.

JJ: She of course was the center, and we all gravitated towards her, and that's the way it's supposed to be. It was about her and what she stood for, the whole tradition of black rhythm and blues performers, putting on a real show. She brought all that, and a church feel. So King Curtis was attuned to all that.

That show at the Fillmore was great, but by the time we got to Switzerland for Montreux we were on fire. When you listened to the recordings from Montreux, they are faster and more intense. Some are available on my website.

Gregg Allman, Derek Trucks, Susan Tedeschi

AAJ: You and Bernard Purdie were at the Allman Brothers 40 Year Anniversary at the Beacon a few years back when they did a tribute to King Curtis. You must have been touched to see how the fans remembered you guys after 40 years.

JJ: I was, and I was pumped up being there, you know, representing, and also being able to express my gratitude to Duane and King Curtis and that whole circle of people, and friends from that time who were part of Duane's life.

That's actually how I got the gig working with Gregg. He called me a couple of weeks later and asked me to join the band. So it was great, everything is a leap of faith, and it turned out that something good came out of being there.

AAJ: And after 40 years, you really are coming full-circle.

JJ: [Laughing] My life's had a lot of full-circles!

AAJ: Are you enjoying playing with Gregg Allman?

JJ: It's a great opportunity to see a lot of my fans. They come out and bring me recordings I've done, and I go, "Wow, you've got this!" We share a lot of the same fans, because going back Gregg and Duane's music intertwined with mine. The same with their styles, they were into jazz, country, blues, R&B, and rock—you know those cats were swinging.

Gregg has still got the same flavor and mentality about music, and he's looking to make new music and to play different types of music. So playing with him gives me a great opportunity draw on my arsenal of styles that I've played over the years. We play some country, some jazz, some blues, some rock, some pop, you name it. And however people want to describe it, his hits.

Because of all the different styles you get all kinds of people coming out: bikers, hippies, straight-up guys, and Southern blues guys. So the audience is different, it's a conglomeration, old and young, they bring their kids, the grandparents are there. It's wild, people will follow the bus for three or four hours just to get an autograph.

It's a great experience to play with a super star like that, an icon.

AAJ: I caught you guys at the show in Bonn last summer, when you were touring Europe. That was the one where you guys were with Derek Trucks and Susan Tedeschi. I remember a couple of days afterwards the news came out that you were going to have to cut off the tour because of Gregg's health. All the people I know who saw it were amazed—my immediate thought was wow, that guy is a real trooper. That was a great show, and I would have never guessed Gregg was ailing.

JJ: That was a truly great show, I remember because I kept a big poster of it and had everybody sign it.

AAJ: I remember when Derek and Susan sat in with you guys, and you and Susan were connecting on stage, it was really special.

JJ: We did, and we had a great time. Every time I've played with Derek and Susan it's always been a lot of fun. It's great to see these younger people coming up and embracing the musical tradition and caring it on.

AAJ: They've got that gift of carrying on the tradition, but also leaving their own mark on the music.

JJ: They really are something. In fact it was a friend of theirs, Jack Devaney, who is responsible for me getting into the Gregg Allman camp. I think he introduced me to Derek first, then Otiel Burbridge, and then Susan; and eventually I met Gregg.

They are really good people, and they are an extension of Duane and Gregg. That's still what Gregg is about, they are all solid people who want to do good and make great music.

Derek's playing is unique. There's a great rhythmic aspect to his playing, his technique and that strumming thing he does—what can you say, he's just got it, he's making new music on the instrument every day.

AAJ: One thing he and Duane share is that horn quality.

JJ: Yeah Derek loves listening to melodic things, and his interest runs deep in John Coltrane and the whole jazz world. He's deeply involved in making improvisational music.

AAJ: I wanted to mention a couple of other guys in Gregg's band: Steve Potts on drums, and Scott Sharrard on guitar. I was particularly impressed with them. Scott plays those songs that have been played a thousand times, and he manages to bring out something new, staying true to the feel, but using his own voice and making it interesting. Respect.

JJ: I'm glad to hear that, because they really put a lot of work into what they do. And you know his hero is Cornell Dupree.

AAJ: And he gets to play with you night after night, it doesn't get much better than that.

JJ: He has a blast, and he's really embraced the challenge of playing that music that's been played so often, and is so well known. So he gives them what they want, but does his own thing too. It's a hard job because the music is very guitar-centric.

AAJ: Also I wanted to mention your sound engineer on the tour. With Derek and Susan's band, the sound slipped into a bit of a sonic-blur at times, and although you guys were almost as loud, your sound was very clear and distinct. I was very impressed.

JJ: His name is Michael Jackson, and he hails from Berkley, California. He's an impressive guy and a beautiful individual. Highly intelligent and intuitive. He makes it easy for us.

AAJ: Another thing that stuck me when I saw you with Gregg Allman is that you guys covered the song "Ridin' Thumb." That really blew me away, because I'd forgotten that King Curtis had covered that song. I remembered it from the original, it was on an obscure Seals & Crofts album that was released before they signed with Warner Brothers. I thought, "How in the world did Gregg find this?"

JJ: You know what, that's the last recording King Curtis ever did, we finished recording that right before he was killed. The last song he ever recorded was "Ridin' Thumb."

I'm not sure how he came upon it, but he was always listening. And he was like that, he'd hear a song on the radio on Monday and he'd cover it, and by next Monday [laughing] it would be pressed, packaged, and ready for delivery.

He had the connections and the company behind him to do stuff like that. Let me think, "A Whole Lotta Love" was a single like that.

Mike Bloomfield and Johnny Winter

Mike Bloomfield and Johnny Winter AAJ: You're actually the first person I've interviewed who knew Mike Bloomfield.

JJ: Ah, Mike Bloomfield. Wow.

AAJ: Well thank goodness Al Kooper discovered those tapes of the Super Session (Columbia) at the Fillmore East from 1968. And then when I heard it, Mike Bloomfield introduced you to the crowd, and I had no idea you'd played together. Did you know Mike prior to that night?

JJ: I knew him prior to that night and up until he died. I remember when he died. Jaco Pastorius and I were hanging out when we heard that Mike had died.

Mike and I worked a lot together in the studio, but there wasn't much chance to get too personal. I can't recall exactly which sessions; it might have been a session with the organ player Barry Goldberg.

Mike was cool, a generous guy, full of love, and he was a great musician..

AAJ: I like to pin down where guitarists' influences are from, but Bloomfield is a challenge in that regard. I don't know if Mike ever mentioned it, but I wonder if Cornell Dupree influenced his playing—not his single note playing, but he and Cornell both had that knack of playing in a way that's not quite lead, and not quite rhythm. Playing groups of notes moving up or down the neck.

JJ: Cornell certainly had that, and it's almost a lost art in a sense. I try to do something similar when I play bass, I have the basic part, but I also have a harmonic or melodic part that's going to intertwine. [Laughs] That's called good taste. Knowing what to play, and when to play it.

AAJ: What really struck me about that Fillmore concert is that it was truly musical history. You guys called Johnny Winter up on stage, and in Al Kooper's liner notes it mentions that concert was on a Friday night, and by Monday morning Johnny Winter had a record contract. You've been part of so many things in your career, but I'm guessing that seeing an unknown skinny albino from Texas with shoulder length white hair deliver the blues so powerfully is something you probably remember.

JJ: Right, I didn't know who he was, like you said, a tall skinny white guy from Texas coming up and playing his butt off. You know, I've done plenty of talent shows, or showcases, so for me that kind of thing was just another day at the office. You do your best to make the people sound good, but you just knock it out, like you know, "Who's next?"

But I'm glad to hear that it paid off for Johnny!

AAJ: Did Al Kooper give you a heads up that he was bringing that out, did you get an advance copy or anything?

JJ: No, I had no idea. I'd heard about it, because there were some bootleg copies going around, and people started sending them to me.

I saw Al at a book signing he was doing out in Long Island sometime after 2000, and I believe that was the first time I'd seen him since the session at the Fillmore. I think I've heard just about all of it, and I've got some nice reviews on it.

AAJ: I have the feeling that if Bernard Purdie had been with you that night, that might have been an iconic recording rather than disappearing in the vaults for over 30 years.

In the liner notes Al Kooper wrote that it was his mistake hiring John Cresci to play drums on that particular gig because he wasn't too familiar with Chicago style blues, and he stepped on your groove. Still, it was an amazing piece of history.

JJ: When those situations occur, it really puts an extra load on me, but it's my job to make the band sound good—sometimes it's easy, sometimes it's hard to do.

AAJ: Let me jog you memory on another time you worked with Mike Bloomfield. He and Nick Gravenites produced Otis Rush's Mourning in the Morning (Cotillion Records, 1969) in Muscle Shoals. What fascinated me is that you and Duane Allman played on those sessions with Mike Bloomfield.

JJ: Mike produced that record? That's funny, it was at F.A.M.E. in Muscle Shoals and I remember Otis, Duane, and Nick, but I don't remember Mike being there. It's been 40 years, that's a long time, but sorry Mike, I don't remember him being there. [Nick Gravenites confirmed that Mike was indeed there. We can look forward to a future interview with Nick].

< Previous

Celebrando

Next >

Portage

Comments

About Jerry Jemmott

Instrument: Bass, electric

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

Jerry Jemmott

Talkin' Blues

Alan Bryson

United States

B.B. King

Duane Allman

Allman Brothers Band

Herbie Mann

Johnny Winter

Aretha Franklin

Ray Charles

Freddie King

Otis Rush

warren haynes

Derek Trucks

Cornell Dupree

Bernard Purdie

King Curtis

Jimmy Herring

Jaco Pastorius

Gregg Allman

Bob Dylan

Al Kooper

James Brown

Herb Lovelle

Champion Jack Dupree

Jimi Hendrix

The Beatles

Nina Simone

Susan Tedeschi

John Coltrane

Steve Potts

Paul Desmond

Charlie Parker

Gil Scott-Heron

archie shepp

Les McCann

Eddie Harris

Idris Muhammad

Lester Young

Cannonball Adderley

Yusef Lateef

Walter Booker

Horace Silver

Jazz Messengers

Count Basie

Carmen McRae

Paul Chambers

bob marley

James Jamerson

Johnny Otis

Etta James

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.