Home » Jazz Articles » Talkin' Blues » Talkin' Blues with Jaimoe

Talkin' Blues with Jaimoe

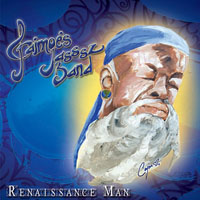

In late 2011 his Jaimoe's Jasssz Band released Renaissance Man (Lil'Johnieboy Records, 2011), an album that is generating well-deserved praise and a lot of buzz. Out front is Junior Mack on vocals and guitar, slide, and dobro, with Paul Lieberman on saxophones and flute, Kris Jensen on saxophones, Reggie Pittman on trumpet and flugelhorn, Dave Stolz on bass, Bruce Katz on Hammond B3 and piano, and, of course, Jaimoe on drums. There is great chemistry and an abundance of talent, and with Jaimoe's musical instincts, the future looks very bright for this band.

Keyboardist Chuck Leavell and now singer/keyboardist Gregg Allman have written biographies, and after an hour of candid conversation with Jaimoe, there's no doubt he could produce a page-turner as well. Amazing stories intertwined with his infectious laughter, what a treat it was to speak with Jaimoe.

All About Jazz: Congratulations on Renaissance Man, this CD was a long time coming, but well worth the wait. It struck me, your band is almost like two bands in one: a jazz band, but when you add Junior Mack to the mix, you also get a blues band with a solid horn section.

Jaimoe: Thank you. Actually, a lot of people had these kinds of bands before, but if you don't tell people something, they'll pretty much go along with what it is. The fact is, jazz is American music. So anything that a musician plays who's coming out of here, it's jazz. It may have originated in Germany, Sweden, Japan or elsewhere, but this is now part of us, and this was developed here. That's what it is, it's improvised music, it's jazz.

AAJ: . Lots of bands would be lucky to have a guitarist with Junior Mack's chops, and most bands would be lucky to have a singer with Junior Mack's voice—he's amazing, you've got the whole package in one, and if that weren't enough, he's writing great songs, like, "Drifting and Turning."

Jaimoe: He's a great musician and a great entertainer, and like you said, he's got the whole package: he plays the guitar, he sings, he writes songs, and he's a businessman. He was a computer specialist for 25 years, and worked for a big computer company troubleshooting, and they laid him off. So he began concentrating on his music, and played what he wanted to.

He ended up never going back. When they tried to call him back in, he didn't do it, and instead he became a fulltime musician.

I met him through a friend of mine named [Hewell] "Chank" Middleton, I've known him since he was 17 years old. We met in Macon when I first moved there in 1968. He kept telling me about Junior Mack. He said, " You don't know Junior Mack!? Frown [Jaimoe's nickname] you gotta meet Junior Mack!"

So one night before I went to the Beacon we met and I said, "Man you got anything I can listen to?" And he handed me this CD, he had it right in his pocket. It was Junior with Dave Stolz, the bassist in our band, and Kris Jensen, our saxophonist, and Dickey Betts. Those guys along with Mark Greenberg, one of Dickey's drummers, and Matt Zeiner his keyboard player, did a gig with Junior and recorded it.

So anyway, I called him up one day and said, "Hey man, I finally listened to your CD. Would you be interested in playing a gig?" Junior said he wasn't too busy, so I called this guy who owns a restaurant called the Double Down Grill in Avon, Connecticut and told him I wanted to do a dress rehearsal. But really it was just a rehearsal, I just wanted to play. I told him he could tell people, it's not going to cost you anything, and you can stay if you want to—you know, I didn't want to interfere with his business.

So I thought, in between the Super Bowl and the last official football game of the season would be the time to do it. We recorded that and put it out as a CD, and I think that's the best thing we've recorded.

AAJ: So that was from the first time playing together, almost like a jam session?

Jaimoe: The first time we ever played together. So there's Live at the Double Down in Avon, and another CD that's a recording of an Ed Blackwell Memorial Concert at Middleton. It's pretty good and the most different thing I've ever done.

AAJ: Ed Blackwell, wasn't he a kind of free-style jazz drummer?

Jaimoe: Yeah, from New Orleans.

AAJ: I've been lovin' the Renaissance Man CD, but I've been mistakenly telling people I think it's one of the best debut CDs I've heard in quite a while.

Jaimoe: Well, Junior and some other people think if your don't make an album in a studio, it's not legitimate.

AAJ: I don't know about that, the Allman Brothers' At Fillmore East (Capricorn, 1971) wasn't recorded in a studio and that was certainly an album.

Jaimoe: [Laughs] Oh boy.

AAJ: It's kind of strange, the first time I listened to Renaissance Man I thought Gregg Allman must be singing harmony, I even checked the CD credits. To paraphrase Herman Cain, Junior sounds a lot like an Allman Brotha from anotha motha. Have people mentioned that a lot?

Jaimoe: [Laughing] No not a lot, it's pretty obvious when you listen to the CD, but when you listen to him in person, it's a completely different thing. You know, Junior still sings in a men's spiritual group with his church, and he's been doing that for about 30 years. He's also a disk jockey and does a blues show, he's a chef, all kinds of stuff, he's something.

So anyway, during this gig and we took a break, and I told him, "Man you play different than the rest of these guys." And Junior asked me, "Different?" And I said, "Man, I haven't heard anybody play like that since I left Mississippi, with the exception of one other guy, George Baker." He's from Baton Rogue, Louisiana and was the musical director for Marvin Gaye for about 12 years. They play very similarly, but George is more of a jazzer, but otherwise they are very similar.

Like Junior, he's got a great voice, he's a great guitarist, and he writes, but two completely different people. One's no better than the other, just different. But anyway, I told him, "You don't play like Derek, or Warren or any of the other guys. Don't get me wrong, it's just different, you've incorporated less rock into your playing, you're more bluesy." And Junior said, "Well how should I take that?" I said, "Don't worry about it, just keep doin' what you're doin'!"

So we did that gig, and I started thinking, I've got a bunch of guys here, so I need to think about keeping them together. So we started doing birthday parties and weddings, and that paid a lot better than what these clubs wanna pay you. So we did that for a while, and then we got the itching to be on the other side.

So I talked to this guy who's been booking the Allman Brothers since we've been together, and he booked us. The rest of it is pretty much what it is.

AAJ: Man it really worked out, you guys clicked.

Jaimoe: I couldn't have ask for more. I've heard some CDs and thought, "I sure wish I could have recorded something like that." I remember George Porter Jr., the bassist from The Meters, after they broke up, he released Things Ain't What They Used to Be (Independent, 1994) and man, what a record! You hear a record like that and think, "Man, I don't care what anybody else thinks about it, what a record, I really want to cut a record like that."

And I can say, thank God, I got my wish. I couldn't be happier with what we've come up with. And the guys—just great.

You know, I could have had three piano players. Jon Davis who played bebop with me back before I met Junior, Bruce Katz, and one guy who ended up getting shipped back to France. He was a most interesting guy—I called him Inspector Clouseau, because he was a little wiry guy, but he played piano, sang, played guitar and the drums. He was the Thelonious Monk of the band, I would get lost sometimes listening to what he was playing.

So my band was booked for the Wanee Festival down in Florida, you know it's down by the Swanee River. So I'm thinking, how are we going to get him down there? So, he can't fly and he couldn't catch the train, and finally Junior says, "I'll just drive down there, and that will take care of it." Then four or five days before the gig he says, "You know what, I'll just fly down, it will be alright."

And I told him, "Man, don't mess with taking an airplane," but he went down there anyway. Well, as soon as they saw his name, lights and shit went off, and they pulled him to the side. He'd been over here ten years, he just blended in until he went and tried to board that airplane.

AAJ: Man, that's sad.

Jaimoe: Yeah, a really nice guy and a great player, Mathais Schuber is his name.

AAJ: We've got to get you guys over to Europe for a reunion concert.

Jaimoe: Book us!

AAJ: Jaimoe I read that you played with Sam & Dave for a while.

AAJ: Jaimoe I read that you played with Sam & Dave for a while.Jaimoe: No, no, no. It's funny how I can't get some of these things cleared up. Sometimes I think, maybe I should just go ahead and take the free ride. But no, I didn't play with Sam & Dave, however, I did play on quite a few shows that Sam & Dave were on. Like in the Apollo Theater on the Otis Redding tour I did in 1966. Sam & Dave were the co-stars.

AAJ: Is it true that Otis Redding said that he wouldn't be booked on any more tours with them because they were like human-dynamite or something like that?

Jaimoe: No, that's why he hired them in the first place. They put fire on him, you know, when he came on the stage after them, he was quite inspired. See, Otis was one of those guys who was not gonna be outdone. You know, that disease, Little Richard had it, Johnny Winter used to have it, and Jerry Lee Lewis.

You know, they'll get up and perform everything they can think of, so that whoever follows them won't have anything left to play, because they've played everything under the sun! Man I know some guys like that, and I know some guys who took care of them too.

Anyway, Otis wanted somebody who was gonna put fire on him. So when he came out on stage, he was left with no choice, he had to be on fire.

AAJ: That's important to know, because that is out there that Otis didn't want to be booked with them.

Jaimoe: You know, it's not that they were so much more, but it was like, "There's two of them and only one of me." So somebody took something out of context, because Otis loved working with those guys because they put fire on his ass.

Joe Tex, James Brown, Otis, Wilson Pickett and a couple of other guys, they had this thing going, this positive competitive thing. So if one of them ran into another, it was like, "I'm not gonna be outdone." But it was positive, and they were the best of friends.

From left: Dickey Betts, Jaimoe, Gregg Allman

From left: Dickey Betts, Jaimoe, Gregg AllmanI remember one day down in Muscle Shoals, I figured I'd been there long enough, so I asked Duane Allman, "Man, tell me something, why do you want to have two drummers?" And he said, "Because Otis Redding and James Brown had two drummers." So I didn't ask him anything else, I said something like, "Well, that's cool, because I was one of the drummers with Otis." But when I played with Joe Tex and he tried to do that two drummer thing, it never worked like the way Butch and I play, because those guys weren't that kind of player and I didn't know what I was doing. I did that double drumming thing in high school.

There was this guy named Benny Lockhart who was a great drummer, but in football season he played football. I was only a partial drummer because Benny Lockhart and Lem Barney, you know the football player—we all played drums together in the band in high school. At halftime Lockhart would go to the locker room and change into his band uniform, play with us, then change back into his football uniform and finish the game! And that's the truth.

AAJ: That's wild! And the coach let him get away with it?

Jaimoe: As long as he could do what he was gonna do, and the coach was somewhat of a drummer himself. You know, in black schools all kinds of stuff happened, people were basically allowed to do what they wanted to do as long as it didn't screw up something else.

You know, like these guys playing football and baseball—man, there ain't nothing new about that. Everybody did that. Football, baseball, basketball, it just got down to a point where some schools might not stop you, but if someone was a really good basketball player, they might say to him, "You don't want to go out there and play tight end, you're too good of a basketball player." You know, they were afraid he might get his leg broken, a knee injury or something, and then not be able to play basketball.

That's the way it was in black schools, a kind of convenience. Why were they so good at what they did? Because you had to do the best you could with whatever you had. And when you do that, you always find out things that last much longer.

Man I wish they would have had these videos when I was growing up. But then it's also kind of like the way you learn to play the drums in Africa. I heard Max Roach talking about it, the master drummer sits with his back to his student. He makes a sound on the drum, then you make the sound, but you don't see what the hell he does. He just makes a sound on the drums, if you can't make the sound, you don't come back for your next lesson until you can make the sound.

AAJ: Wow, that's interesting, and it breeds creativity.

Jaimoe: Right!

AAJ: I also wanted to ask you, when you were backing Otis Redding, did you ever run into Jimi Hendrix on tour when he was with the Isley Brothers?

Jaimoe: No, he was a little before me. I think he was a paratrooper or something when I was in high school, so he must have been two or three years my senior. He must have been about Otis's age.

AAJ: You guys played with him at the Atlanta Pop Festival in 1970, did you get a chance to meet him then?

Jaimoe: Oh, I knew Jimi before that. When I first went to Macon, Georgia in July 1968, it was to work in Phil Walden's recording studio as a session player for what would become Capricorn Records. I had no idea who the Allman Brothers were when I went to Macon.

Jaimoe: Oh, I knew Jimi before that. When I first went to Macon, Georgia in July 1968, it was to work in Phil Walden's recording studio as a session player for what would become Capricorn Records. I had no idea who the Allman Brothers were when I went to Macon.But they had only just found a building for the studio at that point. So I started playing around town with some guys I knew from being in Otis's band and Percy Sledge's band, and that rhythm and blues circuit. So I was playing with this guy Percy Welsh, who was a drummer for John Lee Hooker in his hot days, and Eddie Kirkland, the guitarist who got killed in a car accident about a year ago. They had played in John Lee's band together, so I was playing with them at Ann's Tick Tock club.

You know the Little Richard song, "Whoa oh oh Miss Ann, you doin' somethin' no one can?"

AAJ: Oh yeah , sure.

Jaimoe: Well we were playin' at that joint for a while, it was still there when I got to Macon in '68. Anyway, one day I get a call from the office down at the recording studio, it was Twiggs who would later become the Allman Brothers' road manager, and he had been the road manager for Percy Sledge when I had been in his band.

He said, "Hey Jaimoe, I got something I want you to listen to man. I've got an idea." So he had an idea involving a guy named Johnny Jenkins, who was a blues player—he played some Chuck Berry and stuff, but he was a real blues player, and a hell of a guitarist.

AAJ: Yeah, didn't he do that song with Duane, "Down Along the Cove?" That's great.

Jaimoe: Yeah, that was a track that was cut in Muscle Shoals for the record they were trying to put out on Duane. They were trying to cut a record on him and Duane even sang on a couple of them, they had picked "Down Along the Cove" for him to sing, and a couple of funny tunes like "No Money Down" about getting a car, and "Happily Married Man."

Jaimoe with Duane Allman's daughter Galadrielle at the 2012 Grammy Awards

Jaimoe with Duane Allman's daughter Galadrielle at the 2012 Grammy AwardsAnd one day Duane said, "Man, my brother is the singer. I ain't no singer, and I'm tired of this shit!" So he stopped doin' it. He was very adamant about it.

So back to the call from Twiggs, they wanted to make Johnny Jenkins into the next Jimi Hendrix. See, when Twiggs was on the road with Little Richard, Jimi Hendrix was the guitarist. And the guy who wrote, "Tell It Like It Is" that the Neville Brothers sing, is George Davis, who was the bassist in Little Richard's band. So George Davis and Jimi Hendrix were in Little Richard's band when Twiggs was the road manager.

AAJ: Holy smoke, that's wild.

Jaimoe: And it gets nicer and nicer on down the line! You know "Mardi Gras Mambo," that was the first song that Nevilles ever cut; they were high school kids when they cut it, young teenagers. And George Davis was the alto player on that.

So Twiggs tells me, "Jaimoe, listen to these records. I'm gonna be back in a couple of days, and I want you to tell me what you think of it." Well if it hadn't been for those records, I probably would have never played in Duane Allman's band, or anything like that, because I thought all that shit was loud-ass music. And I had no desire for it, because it was so damn loud you could never hear it well enough to understand it in the first place.

So I sat down and listened to these records he brought me: Are you Experienced (MCA, 1967) by Jimi Hendrix, a Greegree album with Mac Rebennack, Time Peace: The Rascals' Greatest Hits (Atlantic, 1968), and Disraeli Gears (Atco, 1967) by Cream. He came back and I said, "Them cat are playin' jazz." So he says, "You like that huh?" And I said, "Yeah man, I like it."

So he explained his idea about Johnny Jenkins. When he was out on the road with Little Richard he had taken some Johnny Jenkins records along and played them for Hendrix. And Hendrix liked them. So Twiggs had this theory, that some of the stuff that Hendrix was now playing was stuff that he had picked up off of the Johnny Jenkins records. So he thought he could create this Jimi Hendrix character out of Johnny Jenkins. And I'll tell you, it didn't work.

We created The Johnny Jenkins Blues Revival. I was the drummer, and a guy named Ron Graybeal was on bass. So that's when I met Hendrix, it was 1968. They came to Atlanta and I couldn't hear shit, they were just as loud as everything else. They had amplifiers stacked up completely across the stage, and at least three high. But you couldn't hear anything they were playin'!

But Jimi was a nice guy. I became real good friends with those guys, not so much with Jimi, he was kind of a quiet guy off to himself, but Mitch and Noel Redding up until their deaths. Especially Redding, whenever he would come to New York he would always find me, or I would find him.

The last time I saw Noel, he came to a joint in New York City and I was doin' something in a kind of All Star band, Warren Haynes was in it at one time, Bernie Worrell who played keyboards for Parliament-Funkadelic, and a few more guys. So anyway, my wife tells me, "Hey, that guy wants to see you." And I said, "What guy?" And she says, "That bassist from Jimi Hendrix." I said, "Noel?" She said, "He stood there I don't know how long waitin' to talk to you."

[Laughing] When I figured out who she was talking about, I realized Noel had died his hair jet black. So I went looking for him and couldn't find him, and not long after that he died.

And in 2008, Mitch Mitchell died in Portland after a gig, a Jimi Hendrix tribute thing. He played the gig, went back to the hotel and died.

AAJ: You know on stuff like "Manic Depression" and "Fire," Mitch Mitchell had some chops.

Jaimoe: Oh man, Mitch was a hell of a drummer.

With The Johnny Jenkins Blues Revival we played this club on 42nd Street in New York for about a month, and everybody and their mammy came in there. Quite a few of them would sit in, but Jimi would never sit in. Jimi would just come in there and sit with his entourage of women, just a slew of them!

They'd just kind of swam in the place and swarm out. They reminded me of bees, the way Jimi would move and whoever was with him. But all these cats would come in, we played with Johnny Winter, Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady before they were Hot Tuna—they were still in Jefferson Airplane then. Man a lot of people sat in with The Johnny Jenkins Blues Revival when we were there.

AAJ: The Allman Brothers opened for B.B. King and Buddy Guy for four nights at the Fillmore West in January of 1970. Could you share something about that?

AAJ: The Allman Brothers opened for B.B. King and Buddy Guy for four nights at the Fillmore West in January of 1970. Could you share something about that?Jaimoe: Oh boy, oh boy. When I was talking about those guys like Little Richard, early Johnny Winter, and Jerry Lee Lewis—well Buddy Guy was another guy like that. When the gig was all over they had a jam session, and that night Buddy pulled one of those deals.

So after that show, the talk among the musicians, and if you ask anyone from the Allman Brothers Band about that, this is what you'll get. Buddy got to soloing and he tried to play everything he could think of, and dancing, the whole bit. And when someone else would be soloing, right in the middle of it, every chance he got Buddy would be jumping in. And B.B. King got a chair, and pulled it up after one of those solos, and said, "Hey Buddy, you wanna sit down and talk about it." That went all over the damn building, everybody heard that. So if you ask the musicians who were there, that's probably what you'll hear, B.B. tellin' Buddy to come sit down [Laughing].

AAJ: Then there's the story of Eric Clapton coming to see you guys with Tom Dowd in Miami, when Duane looked down and saw him and stopped playing. I wondered, how well do you remember that concert, and when did you first discover Eric was sitting in the front row?

Jaimoe: I don't think he was sitting in the front row, I remember him standing over to the side, and it was in the afternoon, about 3 o'clock or so. Tom told Eric that Duane was playing at this gig, and I remember Tom later saying that Eric said something like, "You mean the chap, the slide player from Rick Hall's studio?"

So yeah, Clapton wanted to immediately go down and hear him play. Something that freaked Eric out, and I saw the same thing with Sonny Rollins and Coltrane—Eric Clapton wanted to know how Duane Allman could be such a great guitarist, and he had never heard of him. You know, where did this guy come from, how could he be all that, playin' all the guitar he was playin'?

I'll tell you something really interesting Alan, what will freak anybody out, is when they hear somebody doing something interesting with a very different approach from what they use, it makes them wonder. I've sat down and studied stuff and come to the conclusion it's all kind of the same, but it has to do with the approach, that's the difference and that's all there is to it. When I tried to figure out how Tony Williams played a certain figure he played on a Miles Davis record when he was only a 17 year-old, I was thinking, "What the hell was he playing?"

So I sat down and I figured it out, playing it every which way, from this hand to that hand, every possible way I could think of to play it, but I still wasn't satisfied with what I was getting. You can break something down, but you can't cop the personality. That's the thing; you can't capture someone's personality. That's the secret to the whole thing, the personality.

AAJ: I also wanted to ask you about the atmosphere during Eric Clapton's 2009 appearances with the Allman Brothers at the Beacon, especially on the second night, that was electrifying.

Jaimoe: You know there are very few musicians, unless they've played together before, who just come out and relax and fall in and play. After the first night, he played and he left. The second night, he was going to play, and then come out and play again. What happened was, he just came out and played, without planning in advance, no this tune and that tune, instead he just came out and played. That's what the difference was.

For myself, I really liked Eric most when he was in Cream. But what I found out at the Beacon is that the motherfucker can play, he can take care of himself.

AAJ: Last question, there was a movie some years back called, Almost Famous (DreamWorks, 2000) which was supposed to have been inspired in part by the Allman Brothers. Did you see it, and if so did it reflect what your life on the road was like back in the day?

Jaimoe: Some people thought it was about Lynyrd Skynyrd, but there was a band in Warner Robbins, Georgia called Stillwater, and I thought the band they portrayed in that movie was more like a Stillwater band than anybody.

I remember when it came out, somebody said, "Man you wanna go watch the story of your life, go watch this movie." Well I saw the movie and I said, "The story of whose life?" If it were the Allman Brothers story, it would have to be put through a very, very high tech health department before it could be released [laughing]!

In an unsanitized Allman Brothers Band real life story, the promoter played by Marc Maron in the Almost Famous movie wouldn't have come off so easily.

Twiggs Lyndon, the road manager mentioned by Jaimoe, allegedly stabbed a club owner three times with a knife and was arrested for murder on April 30. 1970. His defense lawyers pleaded temporary insanity because of the stress of living on the road with the band— and he was acquitted by the jury.

Photo Credits

Page 1: Carl Vernlund. All Rights Reserved

Page 3: Carter Tomassi, messyoptics.com

Page 4: YouTube screen capture

Page 5: Courtesy of Jaimoe

< Previous

Obsession

Comments

Tags

jaimoe

Talkin' Blues

Alan Bryson

Shore Fire Media

United States

Otis Redding

Allman Brothers Band

Chuck Leavell

Gregg Allman

Ed Blackwell

George Porter

Thelonious Monk

Johnny Winter

James Brown

Max Roach

Jimi Hendrix

warren haynes

Bernie Worrell

Eric Clapton

Sonny Rollins

Tony Williams

Miles Davis

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.