Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Stuff of Legends: Miles and Co. and Kind of Blue

Stuff of Legends: Miles and Co. and Kind of Blue

From the first notes of Bill Evans piano intro it starts to hook you. The resonant tones from Paul Chambers bass tip-toe in and the head to "So What" is played. Then the warm, soulful trumpet enters as a resounding, but subtle, symbol crash from drummer Jimmy Cobb sets off the beginning of Miles Davis' solo and musical journey. That expedition doesn't last for just one song, but an entire album. And not just any album.

From the first notes of Bill Evans piano intro it starts to hook you. The resonant tones from Paul Chambers bass tip-toe in and the head to "So What" is played. Then the warm, soulful trumpet enters as a resounding, but subtle, symbol crash from drummer Jimmy Cobb sets off the beginning of Miles Davis' solo and musical journey. That expedition doesn't last for just one song, but an entire album. And not just any album. It's Kind of Blue, a musical odyssey created more than 40 years ago whose vibrations turned into tremors felt around the world. They can still be felt.

It's been called the musician's Bible. What many consider the greatest jazz album of all time also routinely makes lists of the greatest music of all time. Its simple style belies a music deep in riches, pleasing to fans and critics alike, as well as turning the musicians upside down—something nearly unheard of in one package.

Duane Allman adored it. Herbie Hancock calls it "a doorway for the musicians of my generation," and Quincy Jones says if one album had to explain jazz, that one is it.

And now, marking its anniversary, two books have been released solely to discuss the legendary album and the legendary musicians who made it possible.

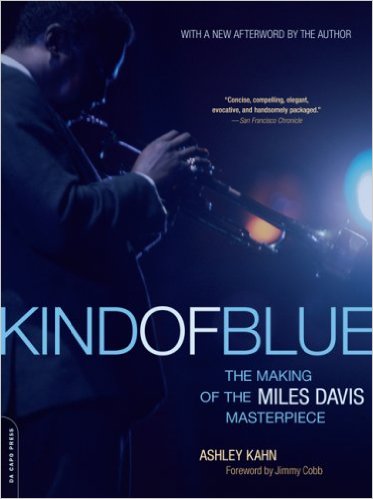

People wanting to know the behind-the-scenes story about the mythic creation—cut in only two sessions, March 2 and April 22, 1959—can do so with the reading of Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece, by Ashley Kahn (Da Capo Press) and "The Making of Kind of Blue; Miles Davis and His Masterpiece, by Eric Nisenson (St. Martin's Press).

Both are roughly 200 pages long and while, naturally, they cover much of the same ground, the tone of each is different, as is the route the authors take to explain this extraordinary music. Both contain interesting revelations for those who like stories behind the stories, as well as those who may be Milesophiles or Coltranians who lust for more inside information about such larger-than-life figures.

Kahn's book (read interview) is borne out of his own appreciation of the record, which he calls "the premier album of its era, jazz or otherwise." He did extensive research on the events by talking to Columbia staffers and various musicians and he presents a tale that begins with how Miles came to prominence and follows the path that led to the development of his special, unmistakable trumpet sound. The trail led not only to "Kind of Blue" but to other groundbreaking concepts by the ever-exploring trumpeter.

The forward of the book is by Cobb, the last living member of the group that laid down that music for the ages: Miles, saxophonists John Coltrane and Julian "Cannonball" Adderley, pianists Evans and Wynton Kelly, Chambers and Cobb. Cobb sheds no great light on the proceedings in the short intro. He remembers being excited because he was to make a record with Miles that day, always an event in itself. In retrospect, he says there was no way of knowing the music would have such a prevailing influence—one that is not likely to ever go away.

Cobb also recalls his fondness for recording in Columbia's studio on New York City's 30th Street, a former Greek Orthodox church that has since fallen to the wrecking ball. It was a venue treasured by musicians for its feel and sound and a site where many superb albums were cut. Kahn devotes a section to it.

Kahn's story follows Miles' early career and how the band was assembled. He explains things like Miles' influence on 'Trane, and how Davis' music evolved from his days with Charlie Parker to the modal form on which "Kind of Blue" is based. The form, while not invented by the group, was packaged and performed in such a way that it shook up the world.

Both authors acknowledge, rightfully so, the importance of George Russell, a composer, arranger and theorist who had been developing the modal form that Miles was so intrigued with. The many conversations the curious Davis had with Russell about modal music were key in the development of the style and the album. Based on improvising on scales inherent in a given note, the modal form allows solos of undetermined length, as opposed to the chord-based system of bebop, which is more structured and established solo length based on "running out" the changes on one's instrument.

The new system confused many musicians at first, even 'Trane, who was profoundly influenced by it. (Without a "map" of chords, Coltrane was at first confused on when to stop his solo, one anecdote has it. "Tell him to take the horn out of his mouth," Miles said dryly, in his distinct manner of cutting to the chase).

Kahn debunks some of the myth about the music. He notes there is evidence that Miles may have written "All Blues" months ahead and his bands may have played it in some form. Legend has it the music was sketched out quickly, handed to the musicians just hours beforehand, and all done in one take. Some of the music was new to the players at the recording session, but, in fact, there were many stops and starts during the recording. (Kahn was allowed to listen to the Columbia master studio tapes...nirvana!). However, the music was completely fresh and the incredible solos invented in the moment. There was only one complete take of each song and that take became the music on the record, except for "Flamenco Sketches," which went through only two takes. (The second is added on the latest CD release of "Kind of Blue").

Both authors explain how Evans was probably responsible for writing "Blue In Green," at least co-wrote some others, and was rankled about the lack of credit he received.

Both authors explain how Evans was probably responsible for writing "Blue In Green," at least co-wrote some others, and was rankled about the lack of credit he received. In his description of the two sessions, Kahn does a nice job of taking the reader into the studio. He quotes some of the conversations gives a nice feel for what went on—things like how Kelly was upset when he showed up and another pianist, Evans, was there. (Miles had developed the album concept with Evans in mind, even though he was no longer in the working band, that seat having been occupied by the Kelly, a brilliant pianist in his own right).

The Kahn book also carries a lot of minutia that may be interesting to fans: where the engineers were located, what kind of tape was used, the number of microphones and how musicians at that time self-regulated themselves in the mix by standing in certain positions or playing louder or softer. He even notes how the first albums had the songs listed incorrectly, and how Adderley's name misspelling (it came out as Adderly) was never corrected until CDs came out.

The book is supremely packaged, filled with photos from the second session (at the first, Kahn explains from his research, no one had a camera. Two people, including one of the engineers, photographed the second). It also has pictures of Columbia memos, including a list of what the sidemen were paid for one session ($64.67 for all except Cobb and Chambers, who received $66.67, including "cartage"). The inside of the front and back cover is classic, coated with the hand-written notes about the music penned by Bill Evans.

Like Nisenson, Kahn explains how the music affected people in that time and how it continues to be not only hugely influential, but still a huge seller.

Nisenson's approach is different. He begins to equate Miles and the music with the societal fabric of the time and draws a parallel with blacks beginning to stand up more against racism.

Nisenson was a personal friend of Miles, long after the "Kind of Blue" era, and some of the observations come from that. One particularly interesting story unveils an admission late one night the author heard Miles make to friends. Davis was notorious about refusing to look back at his music, always moving ahead to new, fresh ideas. But pressed this occasion about what music was most special to him, "Kind of Blue," jumped quickly out of Miles' mouth, Nisenson says. One can almost hear the gravel voice giving the curt admission.

Nisenson gives a short bio of each musician and relates their significance to the project and to music in general. His inclusion of a chapter on Russell is fitting. While most people know about the likes of Coltrane, Adderley and Evans, it is nice to see he calls Cobb an under appreciated musician whose work should place him in the pantheon of great drummers. He also calls Kelly (who played only on "Freddie Freeloader") "one of the greatest of all modern jazz pianists," an opinion that unfortunately, is not repeated enough. (When people say "Wynton," he, and not a certain trumpeter, should be the one that springs to mind).

Nisenson, too, has good anecdotes about the musicians and a sound feel for how and why the music was made. He doesn't quote people on how the music is perceived by others as much as Kahn. Instead, he offers more of his own personal feelings and observations. His chapter on the sessions themselves is less compelling and his research not as wide-reaching as Kahn's. He doesn't give the full flavor of the recording sessions, though his thoughts are certainly not without value.

Some of his points are well thought out and insightful. Others lead to head scratching. It is disconcerting throughout, that Nisenson often makes self aggrandizing references to his other books, speaks in "I was thinking..." and "I always feel..." tones, rather than letting the story unfold for the reader. And, like his book on Coltrane, some of his comments are off the wall. He is knowledgeable, yes, and provides some good information, but he lacks as a writer. His lecturing at times is annoying and his conjecture about music can be baffling. After writing an entire book on Coltrane (which is also speckled with his pontifications) he now professes that 'Trane may have been just a self-indulgent musician.

Nisenson opines that letting Cannonball play on "Flamenco Sketches" was an egregious error (He would know more about it than one of the great musical minds of humankind who hired Adderley and ran the sessions?) At another point, he states that no one knows how Evans began a heroin addict, "but it was almost certainly [through] Philly Jo Jones." Sure, there is no slander when both individuals are dead, but it is a large aspersion to cast without evidence, even though Jones (one of Miles' greatest drummers) was a longtime junkie.

Nisenson's book is also devoid of any photos at all, so is visually bland in comparison.

Both authors skillfully portray how mystifying, and yet how wonderful, the mellow, moody and provocative "Kind of Blue" is to this day, and how it is of immense historic importance.

The choice? Well, for the best perspective, it always good to read both the conservative New York Post and the liberal-leaning New York Times. Both these books have value. If you're only going to read one, Kahn's even viewpoint, broad range of research, better narrative style and the slick packaging wins the day.

< Previous

Boston Boy: Growing Up with Jazz

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.