Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Steve Tibbetts: “Northern Song” and the Sounds of Silence

Steve Tibbetts: “Northern Song” and the Sounds of Silence

With the first four songs completed on the previous day, they are now deep into what will be the side-long "Nine Doors / Breathing Space." Tibbetts plucks ghostly guitar notes while Anderson underlays a foundation of harmonic percussion. Unbeknownst to the foursome, however, things had taken a downward turn.

Via phone from his home in Minnesota, Tibbetts takes a break from helping his kids with their homework to explain what happened. "We were getting pretty tired. Halfway through, Marc's congas went flat, which meant that a whole bunch of loops [pre-recorded sounds] that I had—drones of sitars, orchestral sections, monks—sort of an omelet that I had wanted to use like a Rothko [abstract artist] backdrop to the congas and my playing didn't work. We would have had tri-tones and flatted ninths all over the place. It just didn't work and I was really upset about that. But we didn't have time to re-do it and it was my fault—I didn't notice that the congas went flat. "

In a separate conversation, Marc Anderson elaborates, "Kind of a signature of what we did together was to use drums a lot like melodic instruments, to create melodic motifs, particularly with conga drums. And then be able to put things around them because they were specifically pitched. All of a sudden these loops, which were cool and really did fill the thing out weren't usable."

Tibbetts wanted to redo the recording, a decision not favored by Eicher, whose working style was based on capturing the moment. This was in direct contrast to what Tibbetts was used to from his previous self-produced albums, when he often spent weeks or more at a time on one track. "Manfred was adamant," Tibbetts recalls, "He said, 'I think it would be too much to have all the loops come in.' I felt, 'Well, you think that because you're tired too.' However, that was the way it was done and I wasn't happy about that. We listened to it, and in fact, the more I disliked the record, the more Manfred seemed to like it. He got excited enough about it to call [saxophonist and ECM recording artist] Jan Garbarek and his wife to come over and listen to the final play. When it was over, I went to pack up my gear and Jan came up and said 'I think it's a good record,' and I said it just drove me crazy and I can't stand working this way. He said, 'Yes, yes, I don't think it would be a good record unless you felt that way.'"

Anderson had a different perspective. "Making Northern Song, for me, was fun. It was torturous for him, but fun for me." He ruefully jokes, "It's not the only time in our long history together that something I've done hasn't worked out well for him!"

So upset was Tibbetts at the time that he told the Twin Cities Reader, "Downbeat was correct in giving [previous album] Yr five stars, but this album is just good, it's not great. If people go crazy for it just because of the ECM label, that'll make me sick." ("I was somewhat petulant...young and annoyed" he says now in regard to that article). In the end, Tibbetts didn't harbor any long-standing ill feelings toward ECM. He's recorded all of his subsequent releases for the label, and in fact, one of the highlights of recording Northern Song was the chance to work with Eicher. "[Looking back,] it inspires a great deal of nostalgia," he says. "We worked all day long. We'd go out and have lunch, we'd have goat cheese on hard rolls and talk. I was a huge fan of ECM and I couldn't wait to have our coffee breaks or our lunch breaks and talk to him about Bill Connors and Garbarek and Keith Jarrett, and Eberhard Weber and all these icons—John Abercrombie, Collin Walcott. You know, the amazing conversations we had. And he enjoyed the fact that I knew the catalog. At that point there were only a hundred and something records out, but I knew them all."

Anderson concurs, "I loved being at Talent Studios and with Manfred Eicher and Jan Erik Kongshaug. I had no idea how I deserved to be there so the whole thing just seemed like a crazy dream to me."

Tibbetts had pursued ECM, a label seemingly custom-made for the ambient/experimental sound of his music. He had already recorded, engineered, produced and distributed his first two albums himself. They're dense with ideas, containing guitar freakouts, contemplative passages, and miles of tape loops and percussion. He submitted one, Yr, to ECM, along with a letter composed of cut-up and pieced back together rejection notices he had received from other labels. The combination of this audacious approach, as well as the quality of the music, intrigued ECM enough to offer him a recording contract.

He and Anderson prepared diligently for the three day marathon recording session they were allotted. This set up a disconnect with Eicher's approach before they even arrived, as Anderson says. "We had rehearsed and planned the way we were going to make that record, which Manfred wasn't that keen on. That wasn't his style. His style was to be more interactive and kind of allow the event to happen. But Steve and I came in with a very specific plan: 'We'll track this first, we'll track this next..." We had rehearsed making the record numerous times so that we could actually do it in three days."

Both musicians were looking forward to their first visit to Europe. "We were 27 years old and I don't think either of us had even been to Mexico or Canada, so this was a real adventure for us," says Tibbetts. As the plane landed in Oslo, though, recalls Anderson, "Steve looked out the window and said 'It looks like Duluth.' It's not that much different than northern Minnesota." Steve comments now, however, that the light in Norway was different. This echoes a similar comment made by Eicher in ECM: Sleeves of Desire, a book about the album cover art of the label: "At times I experience music 'cinematically.' What is felt through sound becomes a visual panorama. For instance, when I record in Norway, certain impressions and associations have an effect on the work we do in the studio: the light, the intense winter darkness."

The light and expansive landscape is partly responsible for the unique juxtaposition of silence next to sound on Northern Song. In most of the songs, there are times when the music falls away and the listener is left with just the sound of his or her own heartbeat and breathing. The gravity of these passages of silence give the sound around them more meaning, more significance.

In general young musicians want to fill space with lots of notes. So, in retrospect, it would appear that Tibbetts was being especially daring being so consistently minimalist and quiet on his first work for a major label, a shift in direction from his busier prior work. However, he says now that that approach wasn't necessarily an intentional direction at the time. "I didn't originally intend to use that much silence but Manfred liked that, so we extended that and it worked very well on the first side [of the record]. He continues, "I don't think I was smart enough to say that [it was a direction]. That was only my third record. The first record was just sort of a stoner fest, it wasn't very intelligent, it was just me screwing around in a college four-track studio. The second was really learning the craft of recording and all of a sudden I'm on number three. It was not much of a direction at all, I think. It was just a coincidence, more than anything." However, he did realize at the time, that, due to ECM's high standards and state of the art equipment, "If I was ever going to use silence as a color, this would be the time."

This recording philosophy of Eicher's is expounded upon by Ketil Bjornstad in Windfall Light: The Visual Language of ECM. "Being produced by Manfred Eicher is a purification process for a musician. At best, you feel as though you have been freed of several pounds of dross after a studio session. Unnecessary notes and phrases suddenly become especially conspicuous, because the producer has consistently made it clear that silence is the very prerequisite for music. This forces the musician into an asceticism that is, paradoxically, liberating." This method would have a great influence on Tibbetts and help shape the direction of his future music. In his press release for 2010's Natural Causes he says, "I like the idea of freezing silence or gaps into the fabric of the music."

No, it wasn't the silences that troubled Tibbetts about Northern Song. It seemed to be more about the focus on spontaneity and not re-recording sections or pieces. In that "petulant" 1982 interview mentioned above, he says "I understand now that you can dehumanize music by taking out all the mistakes. It's just too bad that the process of losing my pants is on vinyl." It was, indeed (along with the focus on silences) a different approach from the norm, but one more in line with the spirit of jazz—a music largely based on improvisation. As Anderson says, "It was about the spirit of the moment, and there are lots of ECM records that are not necessarily great records but Manfred put them out because that was what was happening at the time and he thought it was important. That was an interesting perspective for me to learn about." He continues, "I was already studying and playing drum music and music styles from places where it isn't about reworking. I was performing a lot and it was more of a performance perspective. You know, you get the best performance you get and that's what it is."

Song titles such as "The Big Wind," "Form," "Walking," and "Aerial View" convey a marriage of sound and word. The strong Asian influence present in much of Tibbetts' music is less obvious here, but an openness to non-western music, as well as a reverence for the natural world and big landscapes still prevails. The songs sound like music for a locale defined by the elements and surrounded by a lot of primeval space. Space and sky, time and wind, rock and earth. More accurately, it's the music of a rich wild nothingness. A wild nothingness sometimes dark, occasionally lonely, but just as often warm, intimate and inviting.

Lead track, "The Big Wind," is a good example of what kind of sonic landscapes they were creating: a repeated guitar riff intermingles with resonant, chiming percussion, slowly building until the guitar falls away, leaving only shakers and congas. The guitar slowly creeps back in, accompanied by a short, subtle low roar till it all breaks like a drenching rain and everything eases back down into peacefulness, the calm after the storm.

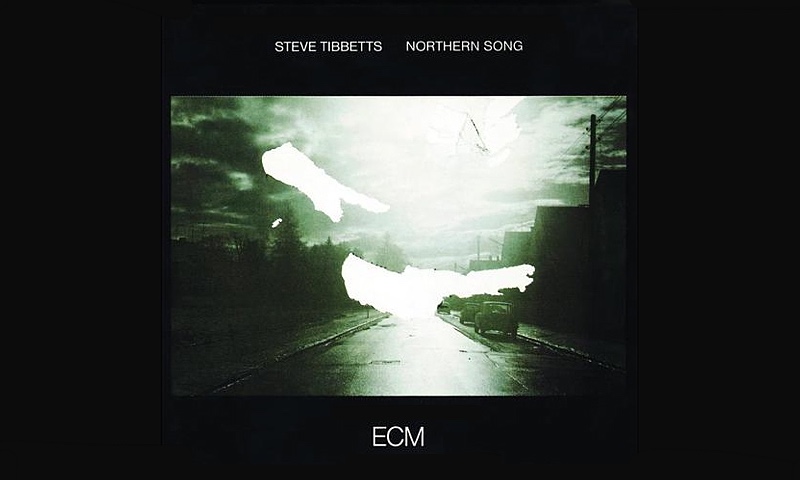

Tibbetts says that many people mistakenly call the album Northern Lights. It could just as easily be called Northern Town, due to the black and white cover photograph of a road, some parked cars, roofs of buildings, a tall pine, and a big sky. The absence of color emphasizes the essentials of form and shape, but here it's through a filter of memory and dream in the overexposed and washed out picture. Some sections have been ripped away, giving it a fragmented feel, as if we're supposed to fill in the missing pieces to this incomplete dream/memory. Lettering (as on most ECM releases) is a study in minimalism, with simple, unobtrusive block letters. It's a particularly successful pairing of album cover and music.

The process of choosing the image took place while Tibbetts and Anderson were still in Europe. After recording was completed, each did some travelling with Eurorail passes before meeting up at ECM headquarters in Germany. Tibbets says, "By the time we got to Munich, Manfred had the office rallied around the project and he had a number of possible covers for us." Photographer Dieter Rehm presented a few options, one of which—a shot of burning grass—later ended up on the Paul Motion album Psalm.

Tibbetts was drawn to one particular photo, though. "[Rehm] was messing around with emulsion and the way that photo looked is the way I felt in Norway. Sort of broken, scratched and clouded over. The light in Norway was different. Shadows were very long and it was overcast the whole time. This is the country of Edvard Munch [The Scream]. Munch was Norwegian and his pictures were in all the hotels and everywhere so it seemed to be 'of a piece.' I was not all that insanely happy about the record, the sun never came out—the sky would lighten around 10:00 and start to darken around 3:00 in the afternoon. The streets looked like the cover and I felt like my own emulsion had been torn off, so it seemed appropriate." The back cover photo of the guitarist and Anderson unintentionally captured this feeling as well for Tibbetts, as he related in the Twin Cities Reader article: "[It looks] like I sat on a syringe full of sodium pentothal."

The title came about in a less readily apparent way, as an oblique nod to The Beatles' publishing company "Northern Songs," which was on Tibbetts mind with the fairly recent assassination of John Lennon. "It's not exactly a tribute, just something that seemed to fit with where we were going, what we were doing, and the two words worked together on many different levels."

Reviews of Northern Song were among the most polarized he has received in his long career.

Stereo Review said, "In a sense, this album is an acknowledgment of the ultimate power of silence over music. Listeners wedded to form and structure and momentum will probably find Northern Song unsettling, even exasperating. Those who can allow themselves to be transported in the few moments a struck chord endures against the power of silence should find it captivating."

On the other end of the spectrum, J.D. Considine wrote in Musician: "Until I heard Tibbetts do it, I never knew that a guitar could hum like my refrigerator. Of course, with the benefit of Manfred Eicher's production know-how, it hums more prettily than my old GE No-Frost, but I'm doubtful if that's enough to make me play the album again. Maybe if they showed me where the ice maker was..."

The Oakland Tribune proclaimed "It has overtones of classical, jazz, rock and Martian style but mostly it is just an extreme pleasure for the senses. Approach with an open mind." Overtones of Martian style or not, Tibbetts is more accepting, if not exactly fond, of the album now.

He feels that Anderson's percussion carries the album and remembers that during recording, Anderson "kept telling me, 'Steve, let him [Eicher] produce it, let him produce it.' In some ways he was a much more experienced musician. He'd played with a lot more people and been out more than I had, so he was a little more ahead of the curve than me."

For the followup album, Safe Journey, recording was wisely done in St. Paul, MN with Eicher only brought into the picture for the mix, which was done in the same Oslo studio as Northern Song. Steve says this method worked much better. "It was very pleasant. I came very prepared, bringing elaborate visual representations of how the mix should 'look.'" "Test," the first track on Safe Journey, begins with a slow fade in from stark silence. Fast percussion with ominous bass tones rising and lurking in the shadows introduce things before a squawk of angry electric guitar. It's not a stretch of the imagination to view it as a protest against the previous album.

Marc Anderson has a tempered appreciation for Northern Song these days. "The last time I heard it I thought, 'Wow, it sounds great, it sounds really good.' I mean, the sound is great obviously. I don't think it's our best record, but I do think it's a really good record."

"As time goes on," Tibbetts says, "it's meant more to many other people than to me. I've met many people travelling for whom it's their favorite record. So, there's something to it. Manfred emailed me a year ago and said it would be nice to work together in the same room again and it might be. It might be good to revisit that. Though, that studio is gone—it would be Jan Erik Kongshaug's Rainbow Studio now. That would really be a wonderful thing to do. I think. At the time, I thought 'I will never do this again. This was a mistake.' But as time goes on, no it wasn't a mistake."

Tags

Steve Tibbetts

Interview

Rob Caldwell

Oslo

Manfred Eicher

Jan Garbarek

Bill Connors

Keith Jarrett

Eberhard Weber

John Abercrombie

Collin Walcott

Ketil Bjornstad

The Beatles

John Lennon

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.