Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » Sade, a Smooth Operator, sings of No Ordinary Love, and ...

Sade, a Smooth Operator, sings of No Ordinary Love, and Is That A Crime?

I suspect that at the core of most personalities is mystery

An Appreciation of the Music of Sade Adu, Andrew Hale, Stuart Matthewman, and Paul S. Denman, who write and perform songs about friendship, love, and sympathy in both cosmopolitan and common lives in a world driven by money and roiled by politics

An Appreciation of the Music of Sade Adu, Andrew Hale, Stuart Matthewman, and Paul S. Denman, who write and perform songs about friendship, love, and sympathy in both cosmopolitan and common lives in a world driven by money and roiled by politics "Wisdom is the flame, wisdom is the brave warrior who will carry us into the sun. I pray that it's swift though tears will come that fall like rain," sings Sade Adu in the "Slave Song" on the band Sade's album Lovers Rock (2000, Epic/Sony). "I see them gathered, see them on the shore. I turned to look once more. And he who knows me not takes me into the belly of darkness" is the beginning of an agony from which the song's narrator and her descendents must be delivered. The lyrics create a mythic image of salvation while suggesting the history of slavery and the struggle that followed, lyrics that are subtle while still being clear. Although the band Sade, made up of Sade Adu, Andrew Hale, Stuart Matthewman, and Paul S. Denman, has written and performed songs with social and historical concerns, they are typically known for songs about friendship, love, and sympathy: "When you're on the outside baby and you can't get in, I will show you you're so much better than you know. When you're lost and you're alone and you can't get back again, I will find you darling and I'll bring you home," sings Sade on the first song, "By Your Side," on Lovers Rock.

Friendship is one of the things I associate most with Sade, recalling one of the band's early videos in which its members sat in a restaurant and walked down a street together, looking very smart, very chummy. Other associations are: humility, sincerity, musicianship, intelligence, and multiculturalism accepted as a fact. Helen Folasade Adu, reportedly the daughter of a Nigerian economics professor and an English nurse, was born in Nigeria but grew up in England. (The band carries her name and consequently is often thought of not as a band but as an individual.) Sade Adu is the principal lyricist for the group, and her method seems to be to admit feelings, quote conversations, describe actions, transcribe observations and perceptions, recall memories, use metaphor, sometimes amazingly fresh metaphors, offer advice and consolation, and declare meaning. Stuart Matthewman plays guitar, woodwinds, and saxophone, Andrew Hale keyboards, and Paul Denman bass; and the music has an acoustic sound—and one can imagine hearing it in a private club or small room, though the group fills large venues. Usually, though not always, the music seems more reflective and plainly declarative than expressive. Although the band has been well known since the mid-1980s, Sade Adu remains something of a mystery.

I suspect that at the core of most personalities is mystery—a hunger for experience, a capacity for pleasure, a need for thought and purpose, a desire to love, and an appreciation of beauty, a life force, that knows itself and knows intuitively there is no object that satisfies, no object that is its natural or sole focus, though it may choose from among those it is aware of. The mystery of who we are and why we want what we want is something we glimpse in other people, and usually the closer we get to the mystery, the more strange people seem; and the farther we are from the mystery, then, the easier it is to accept clichés and conventions about who people are, and the more normal they seem. What's interesting about Adu and her collaborators is that their work together remains the primary language through which her personality and concerns, and possibly even theirs, can be discerned (though the other members have performed without Adu in a band called Sweetback).

Lovers Rock, almost quietly released after a long break, became another popular recording. Admirers and detractors might say that it is predictably a Sade record. (The lyrics are Adu's and the music is credited to the entire band for all but two songs.) In "Flow," love is described as a comfort of nature, with comparisons to sea and light, and Adu sings, "Take up your love and come to me," as if it were the most probable mystical summons. The very affecting "King of Sorrow" has her "crying everyone's tears. I have already paid for all my future sins." Sometimes the only way to say something is to say it, without preamble or apology, and that's what she does, as when she asks for care and truth in "Somebody Already Broke My Heart," singing "Here I am, so don't leave me stranded on the end of a line, hanging on the edge of a lie. I've been torn apart so many times, I've been hurt so many times before, so be careful and be kind.

Lovers Rock, almost quietly released after a long break, became another popular recording. Admirers and detractors might say that it is predictably a Sade record. (The lyrics are Adu's and the music is credited to the entire band for all but two songs.) In "Flow," love is described as a comfort of nature, with comparisons to sea and light, and Adu sings, "Take up your love and come to me," as if it were the most probable mystical summons. The very affecting "King of Sorrow" has her "crying everyone's tears. I have already paid for all my future sins." Sometimes the only way to say something is to say it, without preamble or apology, and that's what she does, as when she asks for care and truth in "Somebody Already Broke My Heart," singing "Here I am, so don't leave me stranded on the end of a line, hanging on the edge of a lie. I've been torn apart so many times, I've been hurt so many times before, so be careful and be kind. Somebody already broke my heart." These seem to be simple sentiments and sometimes, not always, simple songs, but the feelings and attitudes they convey—despair, fear, devoted love, friendship, and understanding—have the largest place to play in human life; and the songs I've quoted thus far require one's whole attention while listening.

"All About Our Love" is an affirmation of love. "Whatever may come, we can get through it," is one line, and though reassuring, it does not, in this case, carry any more weight than it would in life. That may say something about the transparency of Adu's lyrics.

Sade Adu sings in "Slave Song" the lines "I pray to the Almighty let me not to him do as he has unto me. Teach my beloved children who have been enslaved to reach for the light continually" over an almost stuttering rhythm, an almost tribal beat, possibly a form of syncopation. That does not seem merely noble sentiment, but a lurking knowledge that one can easily become vengeful, destructive, ruining not simply an enemy but one's self.

However, when the singer has a conversation with the moon in which she asks the moon to keep her beloved safe in "The Sweetest Gift" the image is at once timeless and a bit too much. (I have read that the song is a lullaby for her daughter, a fact that may qualify, or disqualify, my reservation.) An interesting though not unpredictable aspect of Adu's lyrics—and vision—is how often the innocence of a human spirit embodied in a word or gesture is followed by the world's (or just one man's) betrayal of that spirit, as when in "Every Word" Adu sings, "All the time you were smiling the same smile, I was loving you like a child. I really trusted you. Every word you said, every word you said. Love is what the word was." One may more expect betrayal in politics, in the move from one nation to another, in the jostling of one group against another. "Immigrant," written by Adu with Janusz Podrazik, describes an immigrant who has not been welcomed: "He didn't know what it was to be black 'til they gave him his change but didn't want to touch his hand. To even the toughest among us that would be too much." I find those two lines striking whenever I hear them. I imagine the scene, remember similar scenes in my own life in my native country, the United States of America, and think that those lines and others in the song capture not only the failure to live up to our full humanity but also a betrayal of the often spouted Christianity: "He was turned away from every door like Joseph," and "The secret of their fear and their suspicion standing there looking like an angel, in his brown shoes, his short suit, his white shirt, and his cuffs a little frayed. Coming from where he did, he was such a dignified child."

The title song "Lovers Rock" seems to be more about the spirit of music itself (the urge to create, connect, or express love?), rather than an ordinary personal acquaintance: "I am in the wilderness. You are in the music in the man's car next to me. Somewhere in my sadness I know I won't fall apart completely, and in all this, and in all my life, you are the lovers' rock, the rock that I cling to."

The last song on Lovers Rock is "It's Only Love That Gets You Through," also written by Adu and Podrazik, and it's about a young woman who has gone through hard times while still managing to love. "You know tenderness comes from pain. It's amazing how you love," sings Adu.

Lovers Rock is a good album, but, musically, I thought Sade's Love Deluxe (1992, Epic/Sony), the preceding studio album of new material, was an interesting development. The band's jazz and rock influences were evident in Love Deluxe, but there was also a new tautness in its sound, almost a tension, but certainly a perceptible strength. However, the lyrics of Love Deluxe weren't always as impressive or surprising as those on Diamond Life (1985, Portrait/CBS, though released in 1984 in Britain), Promise (1985, Portrait/CBS), or even Lovers Rock. (I always thought 1988's Stronger Than Pride on CBS was the band's weakest album; and I haven't yet heard all of its' recent live album, Lovers Live, 2002, Epic/Sony, though what I heard seemed similar to the studio versions of the songs.)

Diamond Life, which yielded the popular singles "Smooth Operator," "Your Love Is King," and "Hang On To Your Love," was the album that introduced the band to the world, and my own favorites from the album are "Frankie's First Affair," "When Am I Going to Make A Living?" "Sally," "I Will Be Your Friend," and "Why Can't We Live Together?" Most of the songs on the album were written by Adu with Matthewman, and it is an unusually accomplished, distinctly cosmopolitan recording.

"Frankie's First Affair" is about a charmer who falls in love, someone who now understands the people who had been infatuated with him: "You know now they really did care, 'cause it's your first affair...Where is the laughter you spat right in their faces?...It's your turn to cry." And in "When Am Going to Make A Living?" Adu sings about the ordinary working world: "They'll waste your body and soul if you allow them to," and notes: "See the people fussing and stealing, too many lies, no one is achieving. Have I told you before? We're hungry for a life we can't afford. There's no end to what you can do, if you give yourself a chance. We're hungry but we won't give in. Start believing in yourself. Put the blame on no one else." The song's last line is "Hungry but we're gonna win," and, of course, win she has.

"Frankie's First Affair" is about a charmer who falls in love, someone who now understands the people who had been infatuated with him: "You know now they really did care, 'cause it's your first affair...Where is the laughter you spat right in their faces?...It's your turn to cry." And in "When Am Going to Make A Living?" Adu sings about the ordinary working world: "They'll waste your body and soul if you allow them to," and notes: "See the people fussing and stealing, too many lies, no one is achieving. Have I told you before? We're hungry for a life we can't afford. There's no end to what you can do, if you give yourself a chance. We're hungry but we won't give in. Start believing in yourself. Put the blame on no one else." The song's last line is "Hungry but we're gonna win," and, of course, win she has. I was never sure if "Sally," who opened her arms to many young men, was a friend, a social worker, or a sexual exploiter, as described in the song that bears her name—but in light of the male plights Adu describes and the fact that it is Adu singing, I'm inclined to think Sally's a friend: "Put your hands together for Sally. She saved all those young men...She's doing our dirty work...She's the only one who cares..." The intentions in "I Will Be Your Friend" are unmistakable. "I'll love you for a thousand years," sings Adu.

It is easy to hear how such a thematically varied work would be welcome in an English world as represented in the Hanif Kureishi/Stephen Frears films My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (1987). In his introduction to a collection of his screenplays, Kureishi has written, "This was the mid-1980s—that fevered time...In London new clubs and restaurants were opening to sell-out crowds. Soho was full of people making pop promos and commercials. Good newspapers and magazines were being started. Parts of London seemed gripped by money madness... Sammy and Rosie Get Laid was an attempt to reflect the fragmentation of that time: a young affluent middle class with 1960s values gentrifying working-class areas; riots and the creation of an unemployed and alienated underclass, necessitating the growth and increasing empowerment of the police; and a Third World Muslim whose country was being Westernized, coming to the West and being bewildered by the spiritual chaos he discovers." ( London Kills Me, Penguin Books, 1992.) In a journal about the making of Sammy and Rosie published in the same book, Kureishi writes, "I know now that England is primarily a suburban country and English values are suburban values. The best of that is kindness and mild-temperedness, politeness and privacy, and some rather resentful tolerance. The suburbs are also a mix of people...At worst there is narrowness of outlook and fear of the different. There is cruelty by privacy and indifference...My love and fascination for inner London endures. Here there is fluidity and possibilities are unlimited." ( London Kills Me, p. 163.)

Diamond Life, which sold about six million copies internationally, closes with Timmy Thomas's "Why Can't We Live Together?" and the band's tight groove and the pointed lyrics issue a question and a promise: "Tell me why, tell me why can't we live together? Everybody wants to live together. Why can't we be together? No more war, no more war, just a little peace. No more war, no more war. All we want is some peace in this world...No matter, no matter what color, you're still my brother."

Diamond Life, which sold about six million copies internationally, closes with Timmy Thomas's "Why Can't We Live Together?" and the band's tight groove and the pointed lyrics issue a question and a promise: "Tell me why, tell me why can't we live together? Everybody wants to live together. Why can't we be together? No more war, no more war, just a little peace. No more war, no more war. All we want is some peace in this world...No matter, no matter what color, you're still my brother." One of the interesting things about Adu is that she hasn't become negatively entangled in the racial confusions of our time. I've never heard her asked to take sides in the usually foolish arguments involving race in America. I don't know if things are the same for her in England, Spain, Nigeria, or elsewhere. ("I try to write for the world," said the Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta, who has long lived in England, when asked about her intended audience. Emecheta's reputation, based on books such as The Bride Price, Double Yolk, and Second Class Citizen, has not protected her from acrimonious personal and political attacks from fellow Nigerians. See: Interviews with Writers of the Post-Colonial World, edited by Feroza Jussawalla and Reed Way Dasenbrock, Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1992, pgs. 85-87) Sometimes we actually do accept people for who they are—rarely, it's true—and it's possible that Adu and her band are one case.

Often it is people of African descent in America who insist on racial allegiances. People who see themselves as being on the margins of society tend to both fetishize normality—inordinately adore house, family, job and the symbols of security and success—and also have a special regard for outlawry—self-indulgence, sex, violence, excess of various forms: and they understand the acceptance and rejection of social norms but not indifference to them, not genuine independence. The great thing about "white' history and culture is that there are so many examples and counterexamples of virtuous and vile behavior that one is never in doubt that one is dealing with human behavior, whereas "black" behavior has been so circumscribed, especially in the public or popular mind, between the servile and the transgressive that it is easy to think of an act as very black or not black at all. One can imagine a black man who is heroic or weak by white or black standards but not one who is independent of both standards: it may be then impossible to imagine a genuinely free black man, and that is very dangerous and very sad. Is it possible to imagine a free black woman; and is that what the Nigerian/English Sade Adu is?

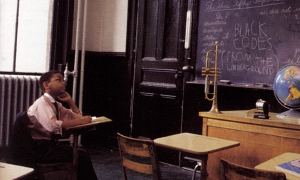

What is the burden of "race"? It is entering a discussion about music and transforming it into a commentary on politics. It is the confusion of subject, object, and meaning. This is exemplified by the substituting of political meaning for personal or artistic meaning. The burden of race? It is an attempt to achieve or contemplate beauty that is then distracted by thoughts of slavery and social discrimination, by the horrors of history—the destruction of personal impression by a terrible historical imprint.

And, Kwame Anthony Appiah has written: "'Race' disables us because it proposes as a basis for common action the illusion that black (and white and yellow) people are fundamentally allied by nature and, thus, without effort; it leaves us unprepared, therefore, to handle the 'intraracial' conflicts that arise from the very different situations of black (and white and yellow) people in different parts of the world." ( In My Father's House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture, Oxford Univ. Press, 1992, p. 176)

Yet, the burden of race is often mindlessly accepted. Sade Adu, a singer and writer and woman who has never slavishly served the market nor politics, deserves better, deserves specific consideration.

The Best of Sade (1994, Epic/Sony) has "Your Love Is King," with the lines, "Your love is king. I crown you in my heart," and "Hang On To Your Love," with the lines, "Gotta stick together, hand in glove, hold tight, don't fight, hang on to your love," and "Smooth Operator," the song about an international lover who lives a "diamond life." Also on The Best of Sade : "Jezebel," a moody ballad, with gorgeously serpentine saxophone playing, is about a girl born with few social assets other than physical appeal, who "when she learned how to walk, she learned to bring the house down." She seems to do questionable things for money and new dresses. Adu's line readings of "Jezebel" are careful, incisive, both sympathetic and tough as she mimes the character's dimensions. "The Sweetest Taboo," is a joyous song, light, up-tempo, about love: ..."If I tell you how I feel, will you keep bringing out the best in me?...You give me, you're giving me the sweetest taboo, too good for me...There's a quiet storm, that is you..." and "every day is Christmas, and every night is New Year's Eve." "Is It A Crime?" is a torchy ballad, beautifully written and performed, moving from detail to detail in language and voice as a woman considers her recent lover's new relationship. Adu sings, "Is it a crime that I still want you, and I want you to want me too? My love is wider, wider than Victoria Lake. My love is taller, taller than the Empire State. It dives and it jumps and it ripples like the deepest ocean. I can't give you more than that. Surely you want me back? Is it a crime?"

Good times come and go, and life, "it's like the weather, one day chicken, next day feathers. The rose we remember, the thorns we forget. We love and we leave, we never spend a minute on regret. It's a possibility, the more we know the less we see," sings Adu in "Never As Good As The First Time," a rather brave and witty song for the band's second album. The lyrics of the song capture youthful resilience, which is very different from the singer's crying, "somebody already broke my heart, be careful and be kind."

"I won't hate you, though I have tried. I still really really love you. Love is stronger than pride," Adu sings on the honest and even wise "Love Is Stronger Than Pride." She goes further: "I won't pretend that I intend to stop living. I won't pretend I'm good at forgiving but I can't hate you, although I have tried. I still really really love you. Love is stronger than pride." And this is a terrific detail: "Waiting for you would be like waiting for winter. It's going to be cold—there may even be snow."

I think "Paradise" and "Nothing Can Come Between Us" are two of the weakest songs on the Best Of album; they are good intentions about good intentions. And "No Ordinary Love"—with the lyrics, "I keep crying. I keep trying for you, there's nothing like you and I baby. This is no ordinary love"—is a song I like, I like the idea of no ordinary love, but the lyrics do not convince despite the singer's insistence. (There are no persuasive metaphors or details.) "Like a Tattoo," written by Adu with Hale and Matthewman, has more imaginative language—about love and deception, sun and a distant river, age and youth—but I don't think it's a truly remarkable song, though the idea of shame worn like a tattoo is not uninteresting, and the music's piano and guitar stylings remind me of music from Spain. Oh, maybe it is remarkable.

"Look at the sky, it's the color of love," and "you gave me the kiss of life," Adu sings in "Kiss of Life," unfortunately another good concept without much illustration. "Please Send Me Someone to Love," a prayer for the well-being of mankind that includes a personal wish for a lover is a thoroughly winning song; a slow dance song, it sounds sweet and old-fashioned and it charms. "You show me how good love can be" is a line from "Cherish the Day," a song of commitment, and when I hear Adu sing the line I believe it, but when I think about the line I doubt it. Thinking about the weaker songs in her oeuvre, it's clear to me that Adu's voice—low, a little rough, warm, sincere—is the element that can determine whether a recording, rather than a song (a song is lyrics and music—form, not merely sound), will be deemed good or not, pleasing or not.

"Pearls," written by Adu and Hale, from Love Deluxe and the last song on The Best Of Sade, is one the band's masterful songs: it's a drama featuring a Somalian woman "scraping for pearls on the roadside"; and the lyrics compare the Somalian woman's state ("she cries to the heaven above, there is a stone in my heart") to the pain of new shoes, an intentionally inadequate contrast, a way of saying there's little in a comfortable western life, and in Sade Adu's life, that compares to such fundamental need. The "pearls" the woman searches for on a roadside for her little girl seem to be fallen grains of rice. (The year before Love Deluxe 's release, in 1991, Angelique Kidjo's album Logozo, on Mango/Island Records, had a song on it, "Kaleta," that presaged "Pearls." Written by Kidjo and Jean Hebrail, "Kaleta," said, "You who watch me from above, you who remain indifferent before the children who are killed, remember that you are not immortal. For he who remains silent before the misery of our children should not forget that suffering and death spare no one.") In "Pearls" the Somalian woman "lives in a world she didn't choose and it hurts like brand new shoes." Isn't choice the essence of freedom? Some of us work hard to have choices; and we convince ourselves we have choices even when circumstances deny them. We insist on the ability to choose our own attitudes to dire circumstances if all other choices are gone. Most importantly, with this song, as with others, it is easy to see that Sade Adu extends to people very different from herself a friendship, love, and sympathy similar to that she feels for her intimate acquaintances, making inequality of wealth, making politics, deeply humane, intelligent, and a fit subject for art. Of course, it was Auden who noted in his "Musee des Beaux Arts" that artists have long known that suffering takes place while someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along; many may know, but not all show. Sade Adu, Andrew Hale, Stuart Matthewman, and Paul S. Denman, and the musicians and producers who have helped to produce their songs, have been creative and more: they have been transformative, transforming passions into believable stories and also the facts of common lives into ideas and images that are hard to forget, something requiring no ordinary love.

< Previous

David Bromberg Live: No Matter What I...

Next >

Rhodri Davies

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.