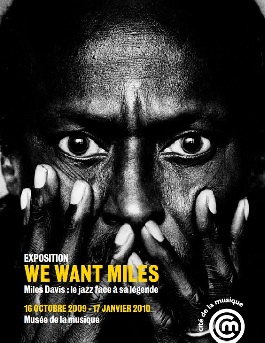

The exhibition “We want Miles - Miles Davis le jazz face a sa legende" is on until the 17th January 2010 at the Musee de la musique in La Villette, in Paris, France. It is an unusual exhibition that gives jazz a rare opportunity to look inside itself and to be seen and heard. We go on a journey through the life and times of Miles Davis guided by the inspirational curator Vincent Bessieres. There is something to satisfy the curiosity of Miles 'virgins', fans and bona fide Miles scholars at this intelligently designed informative exhibition where the visitors are bathed in music. The exhibition follows his career chronologically from his bourgeois childhood in Saint Louis (Missouri) to his concert at the same venue La Villette in 1991, highlighting key associates such as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Gil Evans, Wayne Shorter, Teo Macero and Marcus Miller and the genres he explored from blues bebop and rock to afro-funk and hip hop.

The most resounding impression visitors have while walking around the exhibition is their total immersion in his music. The music is non-stop and thanks to numerous 'sourdines' (Mutes) round auditoriums which give a dozen or so visitors the opportunity to listen to landmark pieces. Besides through headphones, the visitor can listen to more sounds : blissful listening to Miles' suite with Florence 'Jeanne Moreau' wandering around Paris in a scene from Ascenseur pour l'echafaud (Lift to the Scaffold), or escape the crowds for a minute or two to listen to an interview (one not to miss is the interview with Miles on Les enfants du rock in 1986). Also noteworthy is the draped door in the basement gallery which leads through to the famous concert Miles gave at La Villette in 1991, just a few weeks before his death - Miles and Friends, 1991. For every period of his life, the exhibition offers fans a multitude of great photos, (including the fabulous shots by Irving Penn for the launch of the Tutu in 1986) drawings, (the inimitable sketches for the sleeve design of On the Corner by Corky McCoy), manuscripts, instruments and a host of objects and documents. The legendary graphics for the sleeves of the Columbia records in the 1950's, his annotated autobiographical notes and 'To be white' signed by Davis in response to the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter's three wishes. It is all put together with finesse : in black and white for his acoustic period and splashing brilliant colour on electric dreams. We are constantly surprised and dazzled.

Far from merely celebrating the iconic figure of Miles, the show presents his life and work as a paradigm of the history of jazz itself, moving with the times as ever and it demonstrates how jazz is in constant dialogue with other music and art forms which reinvent and enrich it. It goes without saying, that Miles Davis encouraged this dialogue more than any other musician flirting with rock funk and hip hop, he even attempted to get in touch with Jimi Hendrix for a joint project which unfortunately never saw the light of day due to Jimi's untimely death. Ever anxious to fulfill its charter for informative, educational support the multimedia library at the cite de la musique has an e-tool running in parallel that comments on and explains the pieces that appear in the exhibition. We met with Vincent Bessières, the curator of this fantastic exhibition.

DNJ: Why put on an exhibition about Miles Davis in 2009?

Vincent Bessières: This exhibition is part of a series celebrating major musicians of the latter half of the 20th century. It follows exhibitions on Jimi Hendrix, Pink Floyd, John Lennon and Serge Gainsbourg. We wanted to devote one of these slots to a major jazz musician and decided that Miles Davis best represented a musician who was not only highly popular, but someone that would appeal to a wider public, as he was one of the major figures in 20th century music and a personality pivotal to the development of jazz. So we organised an exhibition on jazz with Miles Davis' career creating the main thread throughout. He covered so much ground - from be-bop, to cool jazz, arrangements with Gil Evans, modal jazz - in short over 50 years of ever-changing styles demonstrating the evolution of the genre.

The other reason the exhibition is on this year - 2009 - is to mark a triple anniversary. That of Miles' first trip to Paris, a journey that marked his artistic and personal life. He left the United States in 1949 because he was invited to play as a representative of modern jazz at the first post-war jazz festival which took part in the Salle Pleyel, a classical-music concert hall in Paris. He was only 23 at the time. He was welcomed as a jazz ambassador and hailed in the press, clippings from which are shown in the current exhibition, and there was great interest surrounding him even then. He was taken under the wing of the St-Germain des Prs intelligentsia, notably Boris Vian, as a creative force, not merely a musician who had come to entertain the club crowd. As for his personal life, his relationship with Juliette Greco is the stuff of legend now. She represented emotional and social freedom to him which American society at that time denied him due to segregation. 2009 is also a symbolic year as it marks the 50th anniversary of the release of Kind of Blue, one of the all-time landmark jazz records, popularising modal jazz. It is still the best-selling jazz record of all time. It's a jazz classic.

The third anniversary is the 40 years since Bitches Brew was recorded, an album which marked the advent of jazz-rock and an emblematic shift in Miles' career. After having explored the genre of jazz, he broke through musical boundaries exploring different instruments, rhythms, styles and influences, the like of which had never been seen on the jazz stage. From then on nothing would be the same. Despite a return to traditionalism in jazz, this very reversion is due to a reaction to the irreversible, avant-garde direction in which Miles took the genre, following the recording of Bitches Brew.

DNJ: Was there a major break in Miles' work when he went electric in 1968?

VB: I would rather term the change a turn or a 'detour', as it is described in the exhibition. We see Miles in Germany in 1967, in a suit before an audience in a black and white film in a traditional concert setting. Three years later everything had totally changed: 2 keyboards instead of a piano, an electric bass instead of a double bass, a crazy percussionist bringing fresh dynamic rhythm to the set and a whole new groovy artillery of instruments. The concert is out of doors and the audience is full of hippies. In three short years he had mutated and would never go back. This revolution brought jazz to a whole new audience, but was slated by jazz critics.

DNJ: As curator of the exhibition how did you rise to the challenge of incorporating music?

VB: With the 'Cit de la Musique' and the designer team of 'Projectiles', we wanted to make music central to the exhibition, because that is what we are showing and we felt we had to do it justice. We literally built the exhibition around it, creating little auditoriums: these rooms dotted around the exhibition space mirror the shape of the Harmon mute Miles used, which was a kind of signature for him. These 'mutes' play music, which was fine-tuned by a sound engineer. I wanted to offer visitors direct contact with the music for optimum shock factor. There is also a 'plug and play' system alongside, which allows visitors a chance simply to plug in their own headphones and listen to interviews and a variety of selected pieces.

DNJ: How did you choose the exhibits?

VB: Everything that is on show from the paintings to Teo Macero documents, sheet music, trumpets, photos, videos, costumes, album covers etc. are there to put the music into context. All the exhibits were chosen for this purpose. The sheet music should hold some meaning for visitors, even for those who do not read music. The Birth of the Cool scores are there to demonstrate the work involved in arrangements - the major task of writing as opposed to the work of bop musicians who improvised without music under their noses. Every object serves to highlight different elements of the music, even Basquiat's paintings which, in my opinion, demonstrate the admiration Miles had for both Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker.

DNJ: Why did you choose to exhibit Miles' trumpet and Coltrane's saxophone for example? Isn't that a bit fetishistic?

VB: Miles' trumpets changed with him and the different finished motifs: his signature underlined his personality and his desire to be unique and the various trumpets on show demonstrate this. Showing Coltrane's sax was a way of underlying how that music was a meeting of minds. Kind of Blue is extraordinary not just thanks to Miles, but also to the participation of Bill Evans, Cannonball Adderley, Coltrane, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb. Besides being a touching symbol reuniting these instruments after 50 years, it was important for me to draw the sole focus away from Miles and display some of the meetings, which shaped his career like the one with Coltrane. I wouldn't have included Sam Rivers' sax for instance: he made only one record with Miles in just three months.

DNJ: I am pretty impressed by the relationship with time in the exhibition, was it a determining factor?

VB: I didn't want to slice up each album and create a digest of Miles Davis' work. Some last between 15 - 20 minutes and this was out of respect for each piece. This created a different relationship with time. In addition, to appreciate the evolution of his music it is necessary to take breaks, which slows down the rhythm of the visit to the exhibition. I conceived it as an immersion in the universe of the artist, the legend in a narrative sense, which gets beyond the myth. It follows the story. It is a labyrinth (his family liked the fact that there are no corners: they are all rounded off just as in Miles' home, because he was afraid of corners) but one that uses dark and light - with zones that are lit so as to correspond to Miles' personality, which had stormy moments as well as bright ones).

DNJ: To all intents and purposes he is a very ambiguous character, as some of the interviews in the second half of the exhibition demonstrate.

VB: I didn't want to judge him or single anything out. I wanted to present what a complex character he was without making any value judgments. The end of his life was a rather ambiguous time and this is reflected in the exhibition. His work is presented objectively, as is the man. leaving visitors to make up their own minds.

DNJ: Who are Miles' heirs and how did you collaborate with them?

VB: His official heirs are Cheryl, his eldest daughter for whom he composed a song in 1947; Erin his youngest son who toured a little with his father and Vince Wilburn his nephew, who played on Miles' comeback tour in 1980 on The man with the horn. He was the drummer on the album and co-produced Decoy and You're under arrest in the mid-eighties, as well as playing drums on Aura. He had an intimate knowledge of Miles' music and maintained the network of 'Miles alumni'. His three official heirs took a keen interest in the exhibition and the fact that it was taking place in Paris. They gave very positive feedback and were enthusiastic about the project, but didn't have detailed inventories of their own collections. They had an incomplete idea of what they owned that could be of interest and it was only by going to see them directly and choosing the pieces and objects that interested me in situ that I was able to make those choices. Thanks to their co-operation, I found rare film footage of Miles boxing and studio archives filmed in 1972.

DNJ: In the preface of the superb exhibition catalogue you quote Miles: “I changed the face of music five or six times", why?

VB: 'Birth of the Cool' changed music. Even though when you listen to that record it's far from perfect and badly recorded, but the arrangements are revolutionary and simply breathtaking. 'Kind of Blue' is a different kind of revolution, this time with regards to improvisation marking the end of traditional chord structures. 'Kind of Blue' popularised modal jazz that has influenced numerous other genres of music. Then, his so-called Second Quintet which forms the basis of modern jazz, which didn't so much revolutionise jazz as create ripples which are still felt today. Look at the influence of Herbie Hancock on jazz pianists, or Ron Carter on bassists, Tony Williams' influence on drummers and Wayne Shorter's impact on saxophonists and on compositions, not to mention the way the group played together dilating from the inside out, it's extraordinary. Branford Marsalis' quartet is a direct result of this. Mark Turner grew out of Wayne Shorter. The first two albums of Miles' electric period - 'In a silent way' and 'Bitches Brew' - which heralded the beginning of jazz-rock were incredibly powerful. The ground-breaking way everything was mixed up in the studio - all the riffs, the pedals - was utterly revolutionary in the world of jazz. Miles' radical group really explored this new direction between 1972 and 1975. Marcus Miller's compositions on 'Tutu' made it an album 100% tailor-made for Miles, something that was previously unheard of in jazz. He had a wariness of technology (synths, drum machines, programming) which Miles took in his stride. Even though this music reflects the time when it was made, it has aged fairly well. All in all, I believe that Miles changed the way we look at jazz and jazz musicians.

DNJ: How did he change our perceptions?

VB: He proved that jazz could be popular. Right up to the end of his life he scaled the heights. He was of course not alone in his pursuit of perfection and reinvention and he reaffirmed the fact that jazz was music that demanded respect of the highest order, not just easy listening. There are some who hold very firm views on this point, running the risk of not being understood. This too, in my opinion, is also a way to change music.

DNJ: Did he make jazz more noble?

VB: Duke Ellington did that. Miles Davis proved the independence and sovereignty of jazz, creating a body of work and with it reaffirming his own autonomy. Miles did all he could to reinforce the idea of genius in black music and the fact that an idea of what it should be could not be imposed upon anyone in any way. He believed that this music grew out of the Afro-American community not as a folklore, but as an ability to assimilate European chord sequences, African rhythms, rock riffs and binary funk rhythms. His idea was that all of this could be assimilated, integrated and refashioned. I think that's what he thought. When people asked him: “Do black musicians play better than white musicians?" he never said that there wasn't a difference, nor that black musicians had an innate gift. He said that black musicians have a capacity to hear and grasp rhythms that allow them to do things differently. That fascinates me. He never said you have to be black to play bop, that wasn't his bag, just that having grown up listening to that music you are bound to do things differently. If you want to play in a binary way, you can. He described a real autonomy and independence and was someone who would never be dictated to in any way. Yet Miles is not a major figure in the struggle for racial equality, he was a symbol of it. He drove around in a Ferrari under the police's nose, put Frances Taylor on the cover of the album “Someday my prince will come' and was a staunch supporter of the idea that jazz musicians would never be told what to do or how to play. These actions spoke louder than words and reinforced his own freedom. This is how he chose to take part in the struggle, not marching but just being free-minded.