Home » Jazz Articles » London Calling » Spring Heel Jack: John Coxon and Ashley Wales

Spring Heel Jack: John Coxon and Ashley Wales

Spring Heel Jack's roots were in dance music, with the duo being strong on electronically produced beats. It was really only on their 2000 album Disappeared that they first hinted at a taste for jazz, when they used John Surman on bass clarinet on the title track, and trumpeter Ian R. Watson (of Lob, among others) on three tracks including "Lester"; On these tracks, the soundscapes played down beats in favour of subtler environments more conducive to freer improvisation, a trend that developed further on Masses and Amassed. This January sees another development, as Spring Heel Jack play an eight-date CMN tour of England in the company of Shipp, Evan Parker, William Parker, Bennink and J Spaceman.

Spring Heel Jack's roots were in dance music, with the duo being strong on electronically produced beats. It was really only on their 2000 album Disappeared that they first hinted at a taste for jazz, when they used John Surman on bass clarinet on the title track, and trumpeter Ian R. Watson (of Lob, among others) on three tracks including "Lester"; On these tracks, the soundscapes played down beats in favour of subtler environments more conducive to freer improvisation, a trend that developed further on Masses and Amassed. This January sees another development, as Spring Heel Jack play an eight-date CMN tour of England in the company of Shipp, Evan Parker, William Parker, Bennink and J Spaceman. On December 19th, I spoke to John Coxon and Ashley Wales at Coxon's home near Columbia Road flower market in East London. I started by asking them about Disappeared and their contact with John Surman.

John Coxon: We had always been a bit shy of calling people, especially people we regard as musical heroes almost. It was the first time we had done that.

John Coxon: We had always been a bit shy of calling people, especially people we regard as musical heroes almost. It was the first time we had done that. Ashley Wales: On that album, it was the first time we had got anyone else to play anything on our records that we hadn't sampled. Before that, we had done all the stuff ourselves. We had never had a live drummer in or anything like that.

JC: We were quite anti—(AW: Musicians!)—kind of anti-musician. But if you are making beats, to play along to them is not the kind of thing we are really interested in.

AW: Also, the studio we had at the time wasn't set up for that. Trying to get a good drum sound is [difficult]...and then you've got all these fantastic breaks played by Clyde Stubblefield or whoever, that have got great sound, great snare, great bass drum—and if they haven't, you can take one from somewhere else. They have got the atmosphere. Someone has spent a lot of time miking up a kit, and they were great drummers.

All About Jazz: So why John Surman? Why did you start with him?

JC: He is one of the greatest living saxophonists. Ashley had been listening to him since he was about twelve years old. He'd been playing me Surman albums since we met. He is a wonderful player.

AW: The track we did, Disappeared, we were sitting there saying, "God, it would be good to have someone like John Surman playing the bass clarinet on there. I can just hear it." Neither of us could find a whole... we didn't want to make a composite. So we thought maybe we should get him to play on it, if he would like to do it. He was the man for the job. That was what that track needed. It was a great track beforehand, anyway, but his playing on it was wonderful. What a beautiful instrument bass clarinet is.

It always sounds bad, that we just rang John Surman up.

AAJ: Why?

JC: It sounds presumptuous. Especially us who are not able to play instruments like that. I play guitar; Ashley plays trumpet. But it is not like these people?

AW: They are consummate musicians. That is what they do. John Surman plays baritone sax, soprano, bass clarinet, alto clarinet, recorder, whatever. He is a fantastic musician and always has been. It is a little bit presumptuous to say, "Do you want to play on this electronic soundscape we've made in the studio?"

AAJ: So, you had the track and then you thought John Surman would be good over the top of it, rather than thinking of him and then conceiving the piece?

JC: Yes, we wrote the piece of music first. And this is the pattern we have followed since then. Originally with Masses the idea was to have individual voices on each track, but then we got more and more interested in the group improvisation thing.

AW: It is difficult if you have a separate player on each piece. What is it?

AAJ: A compilation album.

AW: Do we want to make a compilation album? No we don't. That was always the problem with a lot of drum'n'bass albums. They sounded like compilations of 12" singles. You want something a bit more coherent. If we'd have had soprano sax, trumpet, trombone, what would it mean? Is it like separate sonatas? Is it like a Poulenc album? Flute sonata, clarinet sonata, trio sonata? You know what I mean? You see those albums where they group all their instrumental works together. We didn't really want to make that because they are sort of unconnected, in a way, other than being by the same person.

JC: So when it came to Masses, as we developed the idea, as we wrote the pieces, it became clear that it would be better to do some whole group improvs, some duets, some trio ideas. We kind of developed the idea as it went on. But in a way, it started with that John Surman track.

AW: That was definitely the catalyst. We had talked for years about how great it would be if we could get all these musicians together. One of those things we would sit around and talk about in the studio when we were having a cup of tea.

AAJ: And with Surman you found that if you phoned him up he would do it?

JC: In fact we didn't even meet him. We sent him the track on DAT and his son recorded him doing it and then dropped it off. So it was nice to develop the idea.

When we met Peter [Gordon] from Thirsty Ear, we had this idea, and he mentioned the idea as well, because he had started The Blue Series with Matthew Shipp. So the whole thing developed from there.

AAJ: So how did you decide who to use on Masses?

AAJ: So how did you decide who to use on Masses? JC: A lot was to do with who Matthew was working with already—duos, trios or the band playing with David S. Ware, that group of people. The only people who we would have liked on it but who aren't were Gerald Cleaver, who wasn't available, and Wadada Leo Smith who lives in California. Daniel Carter is an undervalued player, who we knew nothing about beforehand.

AW: The same with Roy Campbell. He was fantastic. What a trumpeter! And a nice bloke as well. He got it straight away. He and Mat Manieri.

JC: The two of them really understood what was going on, more than anybody else. That sounds bad, like other people didn't understand what we were doing, but they clicked with it so immediately. I think Tim Berne understood because he has done that sort of stuff, re-recording and layering. But the duo that Mat Manieri and Roy Campbell played—"Cross"—was amazing. Mat Manieri was a revelation as well. In a way, the people we made Amassed with we knew a lot about. The people we made the first one with we knew less about.

AW: We had hardly heard any of Matthew's stuff. Now we know there is tons of it out there, but we just didn't know about it. I have been listening to the European people for years, and then other things came along like punk and dance. At the end of the day, you find that these people are still playing—well of course they are still playing! They haven't spent years pogoing or necking E's. They have carried on doing what they are doing, and it is even better.

JC: Their attitude appealed to us as well. These people have put their whole lives on the line, in a way, to play the music they believed in. That is a real jazz truism but it is so refreshing that the idea is to make exactly what you want to make, exactly how you want to make it and fuck the consequences, whether one person buys your record or nobody buys it. In some ways, drum'n'bass did as well, although it became very commercialised; you make what you believe in solidly, outside of any commercial pressure. That is what music is about. Certainly since Beethoven, the idea of an artist doing what they want to do in the way they want to do it has become a norm. But people have to make a living?

AW: Even Bach did. He had to write a cantata every fucking Sunday for the whole year. But it is still Bach.

JC: What's that one? The Peasant's Cantata ? Dreadful.

AW: Not my favourite Bach. But doing that enabled him to write The Art of Fugue.

JC: Part of the admiration you have for any musician or composer is that they stay true to themselves. The people, who we have made these last two records with, we admire them for sticking to their musical principles, through thick and thin, through playing in the subways, playing what they believe in.

AW: Lots of great things came out of punk. Without punk, you wouldn't have had The Pop Group or Cabaret Voltaire or The Gang of Four. After the initial three chords blundering around, there was some great music came out of it. All those influences came into it; you'd hear a Pop Group record and you'd think they are listening to Berio, they know their Albert Ayler, all the dub, all the reggae. But it was "let's just get up and do it." Perhaps the musicianship wasn't the greatest in the world, but it was never bothered with that. It was the actual fact of getting up and doing it.

JC: I've just been listening to that Lee "Scratch" Perry record, Doctor on the Go and it's a great record, twenty years ahead of its time.

AW: All those dub things were, compared to American or European pop music. They were using the studio as an instrument. It wasn't a new thing; The Beatles had done it, people like Berio had done it.

JC: It's like when people—especially Americans—say that electronics in jazz is a new thing. What are they talking about? It's not new. Like when they talk about it accessing music to people who wouldn't hear it normally. That's not the way it is. We're not interested in getting accessible, understandable breakbeats and putting stuff with them. It is not interesting to us.

AAJ: But don't you think there will be people at the tour dates who will not have heard Evan Parker before and who will have been drawn in by you guys doing it?

JC: No. Very few. Jason might have an effect because he is in a famous rock band. And there will be fans of his who come that don't know much about Evan Parker, especially younger people. But I don't think Spring Heel Jack ourselves have a massive fan base of fourteen year olds.

AW: I don't think we are converting anyone to free jazz or improv. In the same way, I don't think we converted anyone to drum'n'bass. It was all out there anyway. Before he did his things with us, Evan had made 220 albums, probably more. I think it is like the library. People say, "No, I can't go into the library." "I wouldn't read that book or listen to that piece of music." Why not? It's there. If you've got a radio and a library, you've got free access to both of them. If you are interested in music, even if you've got no records or CD player, you can just have a radio. You've got access to these things.

AAJ: But there are people who won't cross the threshold to a library because it is a place they don't go to. It is the same with improv.

AW: The actual physicality of watching Evan and John Edwards and Mark Sanders together is fantastic. Or Peter Brotzmann. You'd have to hate music per se, everything, not to be moved by that. I was playing Trombolenium by Paul Rutherford the other day, and there is nothing on it that is unpleasant, avant-garde, squeaky door, nothing. It is just great playing. He is playing beautiful notes there, notes you recognise, sequences you recognise. Some of it sounds like Vaughan Williams towards the end, where he is playing all those natural tunings. This is beautiful, fantastic. Emanem is a great label.

AAJ: What sort of audience are you expecting, when you tour?

JC: Who goes to those kind of gigs? I don't know. There will be some people who go to see Jason. On his own he could fill the Albert Hall. There will be some people interested in Spring Heel Jack who know our stuff from before. And there will be a lot of people who are interested because of the basic core of the band; it is not a very common fixture. People who have heard the record and liked it will come.

AW: Ideally, we'd like it to be packed. But we don't want to just preach to the converted either.

AAJ: I think you will get people way beyond the improv audience. Like at the Adventures in Sound gig at the London Jazz Festival [which featured Evan Parker, Matthew Shipp, William Parker, Gerald Cleaver plus DJ Spooky, Matthew Bourne, and The Scorch Trio.] I couldn't have predicted that audience in advance. It was diverse.

JC: Gerald Cleaver's playing at that was amazing. Not just the playing but his whole demeanour.

AW: It was cool, in a nice way, not in a goatee-beardy jazz way. He was in complete control. He knew what he was doing. Although it was all improvised, you had the feeling that these people know what they are doing, know where they are going now. But you get that at a lot of improvised music. A lot of times you go to a gig and it just comes down to the physical side of things. There is only so much you can play. Even if you are using circular breathing, you have to have a break. What I love is the way there are no nods, no signs, no conducting or conduction, or anything like that. They just seem to know when they have run out of steam and someone is going to take a break. And then the other two are going to get on with their scraping and scrabbling. And then they are all going to come back in again. I especially love the bits where people are exhausted from playing, and you get those really beautiful moments when people are half out of breath but still playing something, so it is wavering or shaking. You get that hush when people are battered into submission. They seem to have this inbuilt thing, like a timer almost. How do they know, without looking at the clock, that it is time to stop? They haven't worked anything out beforehand.

JC: When Jason was talking to Evan, he was asking what happens. And Evan said, "Well, when you are playing you might get a little bit out there, so you think we'll bring it in a little bit, make it more tonal or whatever, and if it gets a bit too tonal you think then we'll break it down." It is sort of instinctive. What is exciting about it is the collective understanding.

People say, "How is the whole notion of electronics affecting the whole notion of jazz?"; In America, they seem to have taken to this idea of hi-tech jazz and all this crap. Ashley and I did an interview with this guy, who knew what he wanted to say, which was that this is changing jazz. Both of us independently had this conversation with him. And it is just rubbish. It is just not the case.

AW: Take Evan Parker. He needs no artificial manipulation towards his playing at all. He can sound like a cat crying or 20,000 geese flying overhead. He doesn't need sound processing?

JC: Nothing needs sound processing. That is like saying you need it to be interesting. Nothing needs it. The thing about the computer, and recording things straight onto the hard disc of a computer, is that the memory is enormous, and you can manipulate it very quickly. Poor John Cage doing it with scissors, the actual process was very difficult, very physical. Now you can record things onto a hard drive, which is like an infinite tape machine, that is all it is. In fact, in our recordings there is very little manipulation of sound at all. Yes, we took Tim Berne and harmonised him with himself; that kind of thing you can do very quickly, to see what happens, see what it sounds like. But, in general, we have respected the greatness of the playing on those two records and let people play. Sometimes we have taken quite a lot out. We have had a big collective improvisation that is not really working. The classic example is "Maroc" on Amassed, where we took everything out except Evan and Jason, because it worked, it sounded good. The computer is just a virtually infinite recording machine. When people play, you can see the sound files, the waveform, and you can move things around if you want to. But to be honest, we don't do very much of that at all. In general, what we do is compose bits of music and have people playing with those bits of music. There is a greater element of control than you would have with Tony Oxley and Derek Bailey playing with a microphone.

The reason the records we have made work well and are interesting to listen to, is that we haven't set ourselves up as propagandists for the electronic idea. Like DJ Spooky's idea of "21st Century Jazz." It is propaganda and is irrelevant. Twenty-first centuries jazz exists without him or with him. It doesn't make any difference. Evan Parker will be blowing saxophone, and that is 21st century jazz. And if he lived to the 22nd century, it would be 22nd century jazz. Propagandising something smacks of record companies trying to sell records, and that is what I hate about it. The notion of new electronic jazz has got to be resisted. The truth has got to be told. It has got to be said that it is not something new.

AW: One of the first things I heard John Surman play was on "Jazz Today" with Charles Fox [on BBC radio] and it was with SOS with Mike Osborne and Alan Skidmore. The first piece was one John Surman had written called "News for the Day" (or something like that). It was him playing soprano sax through an echoplex with a wah-wah pedal and a sequence going on behind him. I remember sitting there, thinking "fucking hell!" but afterwards, Charles didn't say, "20th century jazz!" He just said it was John Surman using pedals. No one said, "This is new." It was just there. I can't remember what else they played on the programme that night, but it wasn't like that. No one said this was the new direction in jazz, it was just what SOS were doing at that moment.

JC: Ashley and I are not consummate musicians and we are interested in composition but I don't think you can go any further than that and say electronics are revolutionising jazz because they are not. In fact, the players are revolutionising our music rather than the other way round.

AW: Electric Miles Davis hasn't revolutionised Wynton Marsalis's playing. Thirty years on, they are still playing Dixieland?.

JC: You could argue that Matthew Shipp is still playing Dixieland, in that he plays "When the Saints Go Marching In."

AW: You should be allowed to play whatever you want, whenever you want...

AAJ: ...without becoming "a movement.";

JC: Movements are really dangerous.

AW: They fuck everything up. Look at punk. Not only did it become mainstream, it became a joke—the mohicans, the leather jackets. It becomes a tag to sell it, to get it into the mainstream.

AAJ: So what do you think of the whole Blue Series thing on Thirsty Ear? Is that a movement? Or is that happenstance, you're just on it?

JC: It is happenstance. Both of us admire Matthew Shipp's playing and his attitude to music. But when we were making records that people said were drum'n'bass records, we had the same thing. People were saying, "Drum'n'bass is doing this to music." And we would say that was nothing to do with us.

It is a good question that you ask, because it would be easy for us to get drawn into the question of what we think of the other records in the Blue Series and how we relate to them. It is a bit difficult for us to answer. I have misgivings about some of the things that Peter Gordon would say, because he is convinced about some things because it is in his interest to be so. But we have a certain alliance with him because he is allowing us to make the records we want to make...

AW: ...and you can't bite the hand that feeds you.

JC: You could say, "What do you think of the other records that combine electronics and jazz?" and I'm not that interested in them. I'm much more interested in the playing of people who have got some freedom to play without being bludgeoned by other sounds. Hopefully, we are able to do that, but it is very arrogant of us, or me, to say that. It is like saying we have respect for such-and-such but other records don't seem to have quite the same respect for the clicks and whirs of an acoustic instrument. So it is a bit difficult to answer. I have got my views and they are quite strong. If I was recording for ECM, I might say about the horrible reverbs or whatever. It is a bit difficult to get into that situation because we have been let —by Peter Gordon and Matthew Shipp between them—into a world which is difficult to get any kind of entry into unless you are a shit-hot improviser or you are part of the jazz tradition that everyone recognises and respects. We are not in that position. So it is very difficult to be too hard about records that you might not like.

AW: It is like religion. Everyone is entitled to believe in what they want. Everyone is entitled to make the kind of records they want.

JC: I have been reading this book by William Faulkner. His great thing is that there is no central truth. There are facts, and there are perspectives on the facts. Depending on how dogmatic you are, you see your perspective on the facts as truth.

AW: What is that Kurosawa film?

AAJ: Rashomon.

AW: Four different views of the same happenings.

JC: How do you translate that into music? That really appeals to me. Having said that, if you look as Masses and Amassed, they are the same bits of music, the same compositions done by different people, one in the American context, one in the European improv context. You could make a record of the same track, over and over and over again.

AW: It's called a remix?

JC: It's not really. I suppose dubs are, but they're functional.

It is interesting that the most rarefied, intellectualised and potentially elitist music is made by the people who refuse to justify that position, such as Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Paul Rutherford, people who are politically very astute and definite about the completely democratic group improvised thing.

AAJ: Are they still like that when you work with them? Paul Rutherford is notoriously like that.

JC: Yes. Paul and Ashley are quite similar in that.

AW: He is old school socialist. He is still a socialist, which I admire in people. These days it's bad to be a socialist. Fuck off! See all the crap going on around you all the time. It is nice to meet people who still believe in that and haven't had it all knocked out of them. I've had it knocked out of me a long time ago.

JC: I found Paul Rutherford really inspiring, the way he is really passionate about political things like the war.

AW: I like that, because we did give up when ecstasy came along. Everything went out the window. It is good that people still think like that and believe what is right. It comes across in their playing, in the music they make. I just wish more people were like that.

JC: It is interesting, because you talk about the notion of control, getting away from situations where people are controlling you or are able to control you. We were talking earlier about making collective improvised music, where we want to be able to control the final outcome, we want to finish the record off. And it is quite an interesting and possibly difficult notion. Ashley was saying that it is nice to be in control of the finished thing, of finishing the thing off. But why should we have more control than Paul Rutherford or Kenny Wheeler or anyone else? By taking things out, why should we do that, why should we have the power to do that? As soon as you go down that route and question everything, then you are in a situation where you need total collectivity, no leader, an anarchic point of view, and one that I totally subscribe to in fact. Except that when you are making a record, you want to be able to take that out if you want to.

AW: That goes against everything that you are saying. It has got to be somebody's record?

JC: The person whose record it isn't is the record company's. Although legally it is theirs because they paid for the recording. That is what is great about the Incus recordings, or whatever, to have your own record label where you are completely in control collectively of what records you release and why you release them.

I was listening to Ascension this morning, and thinking it was a really radical record, and then I put on Free Jazz by Ornette Coleman and it just further out there, right from the start, five or six years before Ascension. It really is much more of a collective improvisation, whereas Ascension has more of a theme. Ashley and I had that in the studio, asking people like Han Bennink to play in a regular way because it has a key, it is not completely democratic pitchwise. You can play a drone in a particular key and people will play along to it, which is a kind of coercion, if you like. Most of our tracks have a key, and it is quite interesting that we are asking people who are interested in playing in a way in which key, rhythm and pitch is not dictated to them in any way whatsoever.

AW: But these people have the ability to play along to a key and still be completely free. Even on a track like "Lit" on Amassed, we didn't write the horn solo for Kenny Wheeler. That is completely Kenny.

JC: He is more of a composer. He is more interested in keys.

AAJ: On control. You were saying about picking particular bits out from a collective improvisation. How do you envisage that working when you play live? How much live manipulation will you do?

JC: We have no idea.

AW: We are not going to do that. We will not have their instruments linked up to something that we control or process. They will be playing what they want to play.

JC: All we can say is that this is the idea we have for it, and see what happens. We will start with a version of a track...

AW: ...and we will start it off.

JC: When I played piano with Han and Evan, Han made a comment that he was following me. That was because I wasn't listening to him as much as he was listening to me. But it shocked me. I wasn't trying to dictate anything from my playing; I was just playing. But live, we would like to represent some tracks from the album; I think that is obvious. If we do "Wormwood" or whatever, that has a key and a pace. That is how we will start it. I don't know what will happen after that. We have very limited experience of playing in that way with those groups of people.

AW: We have a basic set that we would like to do, certain things based on certain tracks in certain places. But we have learnt from experience that if you are playing with these people you can't prescribe what they are going to play, you can only suggest something. They are open for that.

London Calling "Best of the Year" List

Atomic Feet Music (Jazzland Acoustic) With this album, Jazzland demonstrated that the Oslo nu-jazz scene was about more than jazz plus beats. This is acoustic jazz in the tradition of Ornette (and beyond), played with energy and style. Debut of the year.

Derek Bailey Ballads (Tzadik) In a year that was rich with Bailey releases old and new, this album of standards was the most remarkable. If one doubted Bailey's ability to surprise, after collaborations such as Mirakle and Derek and the Ruins, this killed those doubts. But it is as instantly recognizable as any Bailey, and fits seamlessly in with his other work.

Derek Bailey Ballads (Tzadik) In a year that was rich with Bailey releases old and new, this album of standards was the most remarkable. If one doubted Bailey's ability to surprise, after collaborations such as Mirakle and Derek and the Ruins, this killed those doubts. But it is as instantly recognizable as any Bailey, and fits seamlessly in with his other work. John Coltrane A Love Supreme (Deluxe Edition) (Impulse) The only re-release included here, and allowed into the list because of its inclusion of the newly-released sextet versions of "Acknowledgement" with Archie Shepp and Art Davis added to the quartet. I have no need to sing the praises of the original, but these sextet pieces are not mere filler; they have an energy and immediacy that rival it.

This is an appropriate place to mention my favourite jazz books of the year. They are The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD (6th edition) (see last month's London Calling" for more details) and A Love Supreme by Ashley Kahn, a perfect complement to the above album. It tells the background story of the creation of this classic, including interviews with all the surviving participants—most notably Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner and Rudy Van Geldner. It is fascinating, and sent me scurrying back to listen to the record again and again and again.

This is an appropriate place to mention my favourite jazz books of the year. They are The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD (6th edition) (see last month's London Calling" for more details) and A Love Supreme by Ashley Kahn, a perfect complement to the above album. It tells the background story of the creation of this classic, including interviews with all the surviving participants—most notably Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner and Rudy Van Geldner. It is fascinating, and sent me scurrying back to listen to the record again and again and again. Gerd Dudek 'Smatter (Psi) Dudek's first release as leader is a surprisingly straight-ahead but hugely enjoyable jazz album. It also demonstrates that Psi will be more than just a label to put out Evan Parker records.

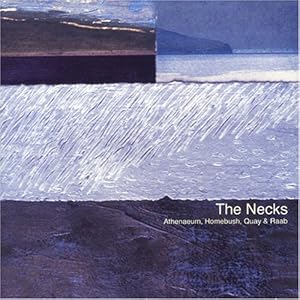

The Necks Athenaeum, Homebush, Quay, Raab (Fish of Milk) The Necks go from strength to strength. Their appearance at the London Jazz Festival was one of my favourite gigs of the year (jointly with Brian Wilson at the Royal Festival Hall, but that's another story). Their last album Aether (on my best of 2001 list) has just been released outside of Australia, to rave reviews. But this newly released four-CD live set, taken from concert appearances from January 1999 through to March 2001, looks set to top it.

The Necks Athenaeum, Homebush, Quay, Raab (Fish of Milk) The Necks go from strength to strength. Their appearance at the London Jazz Festival was one of my favourite gigs of the year (jointly with Brian Wilson at the Royal Festival Hall, but that's another story). Their last album Aether (on my best of 2001 list) has just been released outside of Australia, to rave reviews. But this newly released four-CD live set, taken from concert appearances from January 1999 through to March 2001, looks set to top it. Mujician Spacetime (Cuneiform) Fourteen years into their time together, Keith Tippett, Paul Dunmall, Paul Rogers and Tony Levin are producing music as fresh and vibrant as ever, fuelled by their almost telepathic understanding of each other's playing.

Evan Parker Lines Burnt in Light (Psi) Parker inaugurated his own label with this solo soprano sax gem, his best in a decade. An instant classic.

Spring Heel Jack Amassed (Thirsty Ear) A worthy successor to Masses and a progression from it. See above.

Tomasz Stanko Soul of Things (ECM) Stanko was another highlight of the London Jazz Festival. Just like that gig, this album featured his young Polish quartet, on a programme of moving, original compositions.

Tomasz Stanko Soul of Things (ECM) Stanko was another highlight of the London Jazz Festival. Just like that gig, this album featured his young Polish quartet, on a programme of moving, original compositions. Cecil Taylor Feel Trio Two T's for a lovely T (Codanza) An awesome prospect—ten CDs worth of Taylor, Parker and Oxley on peak form in London, in 1990. Put simply, a lifetime's listening pleasure. Essential.

< Previous

E=Mas Cabeza2

Next >

Take It from the Top

Comments

About Spring Heel Jack

Instrument: Band / ensemble / orchestra

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.