Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Guitarist Fred Fried on 'When Winter Comes'

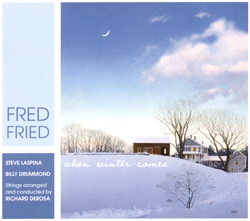

Guitarist Fred Fried on 'When Winter Comes'

I

Fred Fried is a gifted guitarist and composer. He plays with a soft, subtle, and complex touch that takes full advantage of his skilled, emotive compositions. Fried is not only a gifted musician, he is also a man of great thought with whom it is fascinating to discuss music, history—just about any topic at all. Like many jazz musicians, he possesses both a keen intellect and great depth of feeling. It was as a result my distinct privilege to speak with Fried about his latest release, When Winter Comes.

Fred Fried is a gifted guitarist and composer. He plays with a soft, subtle, and complex touch that takes full advantage of his skilled, emotive compositions. Fried is not only a gifted musician, he is also a man of great thought with whom it is fascinating to discuss music, history—just about any topic at all. Like many jazz musicians, he possesses both a keen intellect and great depth of feeling. It was as a result my distinct privilege to speak with Fried about his latest release, When Winter Comes. The conversation took place early in the morning, and after discussing our mutual need for coffee, we began.

AAJ: Could you describe the origins of When Winter Comes, particularly the concept of using orchestrated strings?

Fred Fried: Well, you read the liner notes of course, and that is all true. I knew about Richard DeRosa. I had heard his arrangements on a recording about 12 years ago, so I just called him up. I always tend to write tunes that don’t seem to be your standard jazz vehicles. They seem to be more. There’s more harmony to them. I take melody very seriously. That’s what moves me. Actually, one of the things that got me interested in this whole thing was, strangely enough, Sibelious. Do you know about that?

AAJ: Not the composer?

FF: No, no, the software. The software was named after the composer.

AAJ: No, I’m not familiar with it.

FF: It’s a music writing software that enables you to notate music on the computer... which is becoming quite standard. That and Finale. So I got this just to print out my tunes so people can actually read them—my handwriting is pretty terrible—and turns out one of its features is that you can have your music played back over the computer speakers, by any number of instrumental voices. Now, most of them are terrible, I mean the guitar sounds are awful, everything is awful, except the piano and the string sounds are O.K. So I would write it out how I wanted it, and then I kind of said to myself, ‘Now, I wonder how this would sound on strings?’ And it was so nice hearing these tunes played back, that I was just amazed.

AAJ: Going back for a second to what you said about melody and harmony, one particular track immediately came to mind, “Hold Your Breath”, which has that beautifully penetrating melody. It’s not a typical jazz improv vehicle.

FF: Well, I’m approaching it more like a composer. I’m never thinking, ‘Is this going to be fun to blow on?’ If I did that, they wouldn’t come out anything like the way I want. And, again, some of them are very hard to blow on. I figure that’s a trade off. I want the song to be the way I want it, wherever it’s going to go. Like that piece, it’s got that section where the bass line goes up chromatically with that little motif (humming) and, I don’t know, I just love harmony and like to do different things. Fortunately for me, I didn’t presume to be an arranger, especially a string arranger...so I figured if I want this to be as good as it can be, I’d call Rich and see if he was interested.

AAJ: He did a fantastic job.

FF: Yes, he did.

AAJ: It seems you are both coming from a similar place.

FF: Right. I think he feels the tunes the way I do. To my great wonderment and joy. What he did, he gave them to me all on MIDI first, sort of simulated orchestrations, with simulated guitar sounds and everything...even then, I was struck immediately.

AAJ: So it seems technology is really opening things up.

FF: Well, it’s really a double-edged sword, the advent of MIDI and synthesizers. It really gives the composer freedom and at the same time a lot of what you hear in movies and recordings is not what you think it is. A lot of people have been put out of work.

AAJ: I also wanted to ask about the specifics of playing on a seven string.

FF: Actually, the seven string is getting very popular, though I’ve been playing it for years. George Van Eps invented it. The first one was built in 1938. What it is, is the low A string tuned an octave lower than the regular A string on a guitar... Basically it just gives you deeper range. You can get way down there in the bass register, not quite as far down as a real bass, but not too far from it, and I have found...I can voice chords in ways that you wouldn’t think you could voice them. Meaning, I can put—I don’t want to get too technical here—but I can come up with chords a standard player might not think of. Well, he might think of them, but there are two strings on a guitar where you might usually put the roots, and I can put my root on the seventh string and use the other two for other intervals of the chord. But anyway, it’s just an extended range. Some people just use it to play bass lines, and don’t use it to that great an extent, but others, like George van Eps, obviously do. I think it’s most effectively used when playing the right hand finger style, as opposed to pick, because playing with your fingers you can choose exactly when and which strings, and what notes to hit at what time... If you want to play with blazing speed, maybe the pick is the way to go, although I’ve always said you can do anything with anything as long as you have a mind to do it.

AAJ: In your notes, and just listening to your work, you can hear the influence of the piano.

FF: Right.

AAJ: We hear that a lot, the phrase “playing pianistically”. Could you explain a little what that means, to play pianistically on the guitar?

FF: That’s a good question. What that means to me is that, well, when you listen to a pianist he has two independent hands, and when you’re hearing the chord you’re hearing a line, and the chord’s not stopping because he’s playing a line, or both hands are playing together, or they’re playing harmony together, parallel harmony, any kind of contrapuntal harmony, as opposed to when I hear most guitar players, even when they play solo guitar, what I hear mainly is a chord and then a line, then a kind of punctuation chord, or something like that. It’s not one seamlessly flowing thing that you would hear with a two-handed pianist. And to me I would always rather listen to that... What pianistically means to me is that you have your melody, and harmony, and maybe your bass notes going on simultaneously, and not even always simultaneously, when you listen to a jazz pianist, the left hand is comping chords here and there, but the right hand line does not have to wait for it...the two hands are of one piece. Which is what I strive for, especially on solo guitar.

AAJ: That’s been a development even within jazz piano right? Which brings up the influence of Bill Evans.

AAJ: That’s been a development even within jazz piano right? Which brings up the influence of Bill Evans. FF: Right, right. You listen to him and you hear how he not only plays his harmony but how with his right hand, he’ll harmonize with his right. It’s layered almost. More dimensional.

AAJ: It’s my understanding that that is something that didn’t really develop until later in jazz piano because they were still emulating horn lines.

FF: That horn line concept was so influential, and rightly so, when you heard guys like Lester Young and Charlie Parker playing those lines. Let’s face it, the improvised line is one of the cornerstones of jazz. It’s the horn player. And I think people are more attuned—the audience—to the actual line, and rhythm actually, than harmony. So it’s no wonder, and even if you are going to play like a piano you better be aware of those horn players who played such great lines because that doesn’t mean that you should be playing boring lines because you can harmonize.

AAJ: Which is what Evans was capable of doing.

FF: That’s right. He played wonderful lines with wonderful harmony. So he had it going on all fronts, from all angles. He was quite remarkable.

AAJ: To me the deepest connection I can hear between your playing and Evans’ is the use of space.

FF: That may be true, in that I’m not trying to cram in a lot of lines. To me harmony is what moves me in music, obviously when you talk about harmony, melody, and rhythm in music you’re kind of making academic distinctions here. They’re all part of one another. But for purposes of discussion you have to talk about them. And since I was a little kid, since before I knew what harmony meant, chords moved me, including rock and roll, or even old songs, but they sounded new to me, they just got to me. I think I kinda never lost that. Sure, I get bored with certain harmonic progressions, and I have to go look for something new, but I am always looking for something that touches me emotionally.

AAJ: That is an endlessly debatable topic that I’d love to talk to you about extensively. It’s almost impossible to avoid the word ‘emotion’ when talking about music. It’s something you don’t always find in discussions of other art forms, but in music it’s standard practice.

FF: Music is the one form that bypasses the intellect. As much as players, especially jazz players, need their intellect to play, ultimately, it’s the feeling that gets conveyed. It’s funny. I don’t think you’ll find a musician who will not say that emotions important. I mean, I hear musicians that sound absolutely cold to me, but they’ll say the same thing.

AAJ: Which shows the range of what emotion can mean.

FF: That’s true. What’s emotional to me may not be to them, and vice versa.

AAJ: I think you said it really well when you said, ‘music is the wordless expression of the human spirit’.

FF: ...it’s like when I write, or even when I listen, I’ll analyze later, if at all. I’m just waiting, wordlessly. I wait for the right melody, or the right harmony to come along. It’s not an intellectual process. A lot of work went behind it...but I’ll sit with it, waiting. Some tunes just write themselves, others take a month or more, and I’ll just do a little bit everyday. Basically my criteria is: does it set well with me. Not, “Are there that many bars?” “Does it reach this plateau, and then do such and such?” You might find [that] in a composition book. You want to do this... I think through years of writing, and playing, and hearing music other than jazz, I have an instinct—at least it’s my instinct. I know what I want. I know when I’m happy with something. And I know when to throw something out... You listen to some of the great American composers—Richard Rogers, Jerome Kern, Gershwin—they really had some stuff happening. They could write beautiful melodies. And their concern wasn’t whether [they were] good blowing tunes. A lot of them happened to be... Maybe academics later formulized it. There are books on songwriting. But I think those guys—Irving Berlin, etc.—they had an instinct for melody, and the logic of certain melodies...I mean, do you know a tune called “I’ll be Seeing You?”

AAJ: Yes.

FF: To me—I hope the younger readers don’t say, ‘this guy is an old fogey’—to me if I hear that song, even sung, by someone really good, I think it’s one of the greatest tunes ever written. The way it’s structured. It’s got motifs, the lyric too. It is very sentimental.

AAJ: I wanted to ask my last question about your solo work, and your trio recordings, for example Infantry of Leaves. Could you describe a little the difference between playing in a solo situation, a trio, and in a quartet/quintet grouping?

FF: I really enjoy both. I enjoy playing with a trio, or quartet, but interestingly enough, they both have a different kind of freedom. Playing with a trio you don’t have to lay down the harmony all the time. There’s the bassist, you’ve got the drummer, and you’ve got the interaction. You’re working off one another. You’ve got the form of the tune that you’re playing, in a way though, obviously, I’ll take a few more single lines because it’s not incumbent upon me to get everything happening. In fact, it would be counterproductive to play a bass line while Steve LaSpinna’s playing a bass line. And I’m never going to play a bass line as good as he’s gonna play anyway, but that support, that rhythmic support and harmonic support, is wonderful. That gives you a certain kind of freedom to play on top of that. Playing solo, the freedom is, with anything I want to do, I don’t have to wonder if the bassist is going to be where I’m going to be. Usually, I’m playing a tune in tempo. I still want that rhythm to be solid, but as far as what chord I’m going to play, what substitution, now that’s totally up to me. That’s where I very much like to be creative. I’ll re-harmonize it one way going one time around, and do something different the next. There’s a lot of freedom there. You’re only dictating to yourself. Obviously, you don’t have the interplay, but you know, maybe there is some interplay, between you and the other you, I don’t know. You’re giving yourself ideas.

Visit Fred Fried on the web at www.fredfried.com .

< Previous

Monty Alexander Speaks

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.