Home » Jazz Articles » Genius Guide to Jazz » A Brief, Yet Largely Incomprehensible, History of Blue Note

A Brief, Yet Largely Incomprehensible, History of Blue Note

To narrow it down to the essentials, I pictured the Cliff's Notes of the Reader's Digest Condensed version of Jazz history. To that end, I looked back to my own college years, and called upon everything I still remembered after years of studying music. How much would be left, after decades of lying dormant as I've established my place as the Dean of American Jazz Humorists®? It boiled down to:

- The treble clef looks like a backwards ampersand. The bass clef kind of looks like a big comma.

- FACE and Every Good Boy Does Fine, whatever the hell that means.

- It is possible to play David Werden's arrangement of "Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms" on the euphonium with a blood alcohol content as high as 1.2%.

- Flautists are generally divas or aspiring divas. Women who play trumpet or French horn are difficult to kiss because our embouchures are incompatible. Low brass players are out, both because it's like kissing myself and because one of us ought to be sober enough to drive. Saxophonists tend to be high maintenance. My best bet for any real play is the clarinet section.

And that vital information only set my parents back 12 grand.

I imagined a recent college graduate in the year 2054, sidling up next to a person that his Hottiscope has identified as biologically female with all-OEM parts. Her DNA data-comp of him reveals that his genetic code was custom modeled for optimal long-term handsomeness and earning power, and that she can safely disable his sex drive before his inevitable mid-life crisis kicks in and he leaves her for a 23 year old yoga instructor.

As they begin chatting over a reproduction of a late-20th century 18 year old single malt Scotch from the Boozynth, she decides to test his cultural awareness and ability to appear genuinely interested in what she's saying even though her EmotiScan bracelet says that there's probably not enough blood left in his brain at this point to comprehend a word of it. She confesses her love of Jazz, "particularly the really old stuff like Medeski, Martin and Wood."

Immediately, he's transported back to Introduction to Jazz class from his freshman year. There's no time to access his auxiliary recall on the Cloud, and he doesn't want to risk just reciting a Wikimemory crowd-thought to her. He desperately tries to bring back the stuff his Marsalisbot® autoprofessor kept going on and on about. Words and mental pictures begin flashing in his head, just like back in the day before they banned neural advertising when they discovered the horrifying atrocities the subconscious could make a normal person commit for a Klondike bar.

Louis Armstrong. NEW ORLEANS. Duke Ellington. COTTON CLUB. Miles Davis. COOL JAZZ AND FUSION. KENNY G. NAUSEA AND VOMITING. BLUE NOTE. THE FINEST IN JAZZ.

"Blue Note." he says, coolly.

"Pardon me?" she responds.

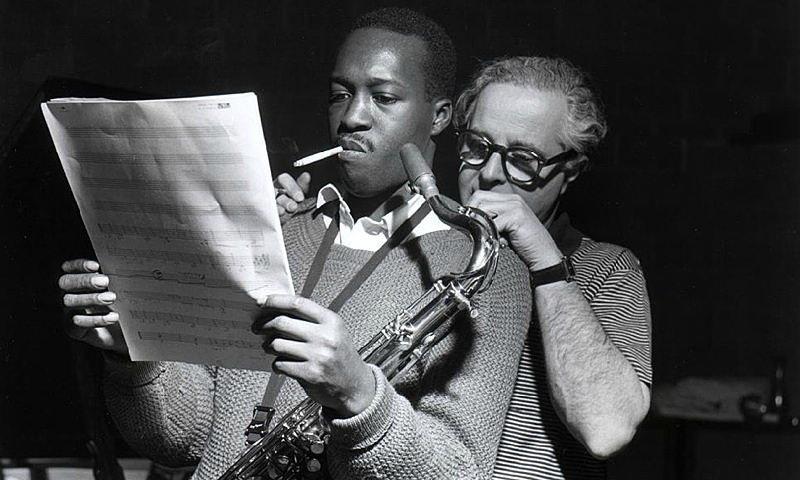

"Blue Note Records. Some of the finest recorded Jazz ever captured on any medium, plus the invaluable documentary significance of Francis Wolff's photographs and the game changing album cover art of Reid Miles. Not to mention Rudy Van Gelder's legendary studio production." he expounds, drawing upon the few salient facts still remaining in the alcohol-soaked corner of his long-term memory containing his early college years.

"Wow, you really know a lot about Jazz." she says, admiringly, as he streams John Coltrane's "Blue Train" directly to her mind-fi enabled Beats by Dr. Dre cochlear implants. Next thing you know, they're back at her place. He dazzles her with corneagrams of Reid Miles's iconic album cover art, while she thoughtcasts futuregraphs of their predicted offspring to the iFrame on her coffee table. As he fills her head with the seductive strains of "Along Came Betty," by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, her Sensescent perfume takes on the characteristics of freshly baked gingerbread both to appeal to his brain's pleasure center and temporarily distract him from plotting the most efficient way to get her bra off. Which is why it is absolutely vital to preserve the elemental components of Our Music's history. Some future couple's awkward, sweaty initial hook-up might one day depend on it. And with it, generations of potential Jazz fans to follow. Especially when Dad has a few too many at Thanksgiving and tells the story of how Blue Note provided the pass code to the Chastitech security device on Mom's undergarments. And Mom thinks twice about reactivating his erectile function for the holidays. There's a lesson there for young boys and girls alike, though I've forgotten exactly what it was.

Let's just pretend those last few paragraphs never happened, shall we?

Blue Note Records is, indeed, the marquis label of one of the most important eras in Jazz history. Founded by German immigrant Alfred Lion and writer Max Margulis (who put up the start-up cash, back in the days when writers actually earned money) in 1939, after the fabled Lost Generation had finally gotten the bathtub gin and existential angst out of their systems and were ready to act like they had some damned sense. The fledgling label began to document some of the most significant artists and achievements in Jazz over the next several decades.

From the very beginning, quality was of the utmost importance to Lion and Blue Note. He approached Jazz with an uncommon seriousness and focus. This was a time when most record companies were content to appeal to the lowest common denominator with saccharine pop tunes, and paid their artists with brightly colored beads and pebbles. Lion distinguished his marque from their competition by going the extra mile to ensure the best quality recording, taking the unheard-of step paying musicians for their rehearsal time. A recording engineer from rival label Prestige, who shall remain nameless because I forgot to write it down, said "The difference between a Prestige release and a Blue Note release is two days rehearsal time."

Lion then began recruiting some of the biggest names in Jazz. When he discovered that it was difficult to fit those large, unwieldy names on the 10" album covers of the era, he changed tactics and went after the premiere talent of the day. The label's catalog reads like a who's who of Our Music: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bud Powell, Art Blakey, Milt Jackson, Jimmy Smith, Lee Morgan, Jackie McLean, Sonny Rollins, Wayne Shorter, Horace Silver, Dexter Gordon, Ornette Coleman, just to name a few that I remember offhand without having to dig out my notes again.

Jazz experienced a period of unprecedented exploration and innovation, and became the soundtrack of the liberated mind instead of just mood music for liquored-up young adults to put the make on one other. Blue Note firmly established itself at the vanguard of this movement, recording some of the most important music of this critical period in the evolution of Our Music.

BeBop, first invented as a musician's reaction to the stifling Swing charts and rigid musical parameters of the day, began to gain a foothold in the late Forties. A liberating, technically challenging, aurally invigorating music that had been incubating in after-hours jam sessions, it represented a paradigm shift from the "good time" music Jazz had always been. This exhilarating new sound was brought to Lion's attention by musician and talent scout Ike Quebec (whose real name was Ike Saskatchewan).

Blue Note's foray into BeBop began in the late Forties with the recordings of Thelonious Monk, who is often called the "midwife of BeBop" (he was present at the birth, but that baby doesn't look anything like him). Monk's seminal recordings failed to garner critical and popular appreciation at first, but soon became recognized for the landmarks they are after people figured out he wasn't an actual monk. Even then, albums by friars didn't exactly jump off record store shelves; not after the commercial and critical failure of Trappist oblate Thomas Merton's Seven Storeys of Swing.

At the dawning of the Rock and Roll Era, Jazz was relegated once again to a genre mostly reserved for people who had jobs and paid bills. The semi-idyllic Fifties set the stage for a Renaissance in American intellectualism, except without the silly hats and all those damned Borgias of that other Renaissance. All fields of creative endeavor prospered in an environment where being smart was a positive virtue, and even being an insufferable pedant wasn't automatically considered grounds for a bitch slap.

The label documented the evolution of BeBop to Hard Bop, a more melodic and emotionally expressive form meant to return Our Music to black audiences. These earliest adopters of Jazz had largely been ignored during the period during which the music was seemingly more interested in catering to the sort of person who were very concerned with the plight of African Americans in society even if they didn't know any of them personally.

By the Sixties, both the arts and society were both straining at their boundaries and experiencing a decay of objective standards. Art became whatever the artist said it was, and "post-constructionist thought" became the accepted euphemism for just talking out of one's ass. Our Music went through its Free period, beginning with Ornette Coleman's warning shot across the bow of traditional Jazz and reaching its apex right about the time Coltrane's conversations with God started to sound like he was drunk-dialing the Almighty.

Blue Note remained steadfast to its mission during this period, remaining open to the best of Our Music whether it was the tuneful strains of Hard Bop or the angular deconstructions of musical form prevalent in the Avant-Garde. But the inevitable winds of change were in the air. Alfred Lion sold Blue Note in 1965 to Liberty Records and retired in 1967 after nearly 30 years at the helm.

Francis Wolff continued on with the esteemed label until he passed on in 1971, some say to avoid having to try to keep a straight face while photographing the ridiculously-attired Fusion groups of the Seventies. How Jazz artists managed to go from natty suits and ties to bell bottoms and half-buttoned polyester shirts in less than a generation is a mystery that fashion historians are still at a loss to explain.

Liberty was purchased by United Artists Records in 1969, who themselves were acquired by European heavyweight EMI in 1979. After a frenzied round of mergers and acquisitions, during which the whole mess was briefly owned by Wild Kingdom's Marlon Perkins (who thought he was buying an Emu for his own "personal use"), EMI eventually phased out the Blue Note label to make more room in record store bins for their roster of openly Swedish artists.

One hallmark of both Jazz and its champions is their indomitability. Jazz has been declared dead more times than Jennifer Aniston's movie career, yet always manages to keep going. Blue Note was simply too great a thing to remain gone forever, much like McDonald's McRib sandwich. And like the McRib, Blue Note represents that uniquely American ideal of doing whatever we feel like and to hell with what anyone else thinks. If we want to eat mysterious slabs of processed pork slathered in a chemically derived facsimile of barbecue sauce and listen to atonal explorations of how many different noises a man can beat out of a piano, it's nobody else's damned business.

Blue Note was resurrected in 1985 both to celebrate its legendary past and to continue its mission to bring the finest in Jazz to discerning listeners everywhere. Not coincidentally, this was the same year I entered Mars Hill College (now Mars Hill University, following a brief period during which it was Mars Hill Discount Tire Warehouse). It was while on The Hill that I learned a full appreciation of Jazz, began to discover my voice as a writer, and tore through the marching band's clarinet section like a tornado through a trailer park.

It was during this period in my life that Blue Note was instrumental (pun unintended, but I'll take what I can get) in my journey to the very heart of Our Music. A double album collection of The Best of Blue Note introduced me to the world of Jazz that existed beyond the hackneyed repertoire of high school Jazz band and the sadly limited bins of small town record shops where the Jazz section contained four copies of Chuck Mangione's Feels So Good album and half of a Mountain Dew someone left there to free up a hand with which to shoplift AC/DC 8-tracks.

In the intervening decades, Blue Note has continued boldly into the future. Though rooted in the greatest Jazz of the mid-Twentieth Century, Blue Note today continues to document the journey of Our Music no matter how far from the familiar that trail may lead. Blue Note has continued their dedication to quality recordings regardless of where that music may (or may not) fit into the traditional categories.

The label has expanded their scope to cover the wide range of new sounds now blossoming in the post top-forty American musical diaspora, in an era where consumers have almost unlimited choices. Music buyers are now free to discover the full scope of sounds that live beyond the soulless, prefabricated corporate product that once reigned supreme in the pre-Digital age.

To that end, the Blue Note umbrella now extends over such labels as Virgin Classics (which doesn't mean what you think it does, perv), Narada (Not to be confused with poet Pablo Neruda, whom, as of this writing, continues to be dead), Back Porch (folk and Americana, for the sort of person who proves my assertion that no good ever came from someone with a Master's degree and a banjo), Higher Octave (Jazz in ultrasonic frequencies, for dogs), and the esteemed Mosaic (reissues in limited edition box sets which, when disassembled and laid out in the proper order, form a larger composite image).

Under the able leadership of Bruce Lundvall, recognized as one of the most powerful men in Jazz with a dead lift of over 850 lbs., Blue Note returned to relevance and reclaimed their rightful place among the most esteemed and storied labels in recording history. Lundvall stepped away from the helm in 2010 to become Chairman Emeritus, which means he gets to keep his sweet parking spot and the card that entitles him to a free appetizer at any T.G.I. Fridays for life.

Lundvall was succeeded by mega-producer, musician and Eighties pop star Don Was as Blue Note's leader. Many view Was taking the helm of the venerable label as penance for him releasing the song "Walk the Dinosaur" on an unsuspecting public in 1988. Remember the band Was (Not Was)? So does he. Which is why he is now singularly focused on continuing Blue Note's well-earned reputation for delivering The Finest in Jazz. It is to be hoped that when my generation faces their reckoning for having produced Grunge, they will do so with the same class and dedication.

So it is therefore resolved that the story of Blue Note is inextricably intertwined with the story of Jazz itself. One simply cannot be mentioned without invoking the other; just you try it and see what happens, Paco.

Till next time, kids, exit to your right and enjoy the rest of AAJ.

Photo Credit

Francis Wolff / Mosaic Images LLC ©

< Previous

Basement Sessions Vol. 2

Next >

Fourteen

Comments

Tags

Genius Guide to Jazz

Jeff Fitzgerald, Genius

United States

Louis Armstrong

New Orleans

duke ellington

Miles Davis

John Coltrane

Art Blakey

Bud Powell

Milt Jackson

Jimmy Smith

lee morgan

Jackie McLean

Sonny Rollins

Wayne Shorter

Horace Silver

Dexter Gordon

Ornette Coleman

Ike Quebec

Thelonious Monk

Chuck Mangione

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.