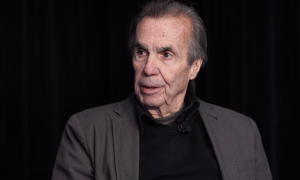

Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Ray Russell: Playing with Time

Ray Russell: Playing with Time

Russell's Now, More than Ever reunites the guitarist with long-term collaborators and old sparring partners, drummers Gary Husband and Ralph Salmins, bassists Mo Foster, Jimmy Johnson and Anthony Jackson and keyboard player Jimmy Watson, in an energized collective performance that brings together the various strands of Russell's long and varied career.

From his session-musician days in the 1960s, Russell went on to play with keyboardist/singer Georgie Fame and the Blue Notes and singer- songwriter Cat Stevens. But jazz was the music that motivated Russell more than anything, and he made a series of critically acclaimed records in the late 1960s and early 1970s that reflected his free-jazz roots. A brief stint in the British jazz-rock band Nucleus in 1971 was happily recorded and came to light with Live in Bremen (Cuneiform, 2003), one of several Russell releases that have been remastered and reissued in the last decade.

Jazz, R&B, rock, fusion, space-rock and more ambient sounds: Russell has turned his hand to them all since the 1960s, and he successfully fuses all these influences on Now, More than Ever. His guitar playing has never sounded as good, and it's easy to see why he's regarded as a musician's musician. And, with a little bit of luck, we won't have to wait quite so long for his next recording, as according to the man himself the creative juices are flowing.

All About Jazz: Did these songs come together in a burst of creativity, or have they been brewing slowly over a period of time?

Ray Russell: It took about a year and a half to get it finished, to get everybody's availability. It's been a bit of an on-and-off project, but I am pleased with the way it's turned out compositionally, and obviously it was great to have so many of my favorite musicians playing on it.

AAJ: Had you tried any of the music out live before you started recording?

RR: Yeah, a couple. The track "Rubber Chicken Diner" started off with a working title of "Country Boy," which was inspired by the fact that many years ago I used to play with [singer] Chris Farlowe and guitarist Albert Lee. Albert was into country music, and the riff at the start of "Rubber Chicken Diner" is really a nod to what we used to play then. A lot of these compositions have a little bit of history to them, although some I wrote in I wrote in a burst of inspiration [laughs].

AAJ: The music on Now, More than Ever sounds like a melting pot of all the different periods of your career and all your influences: the R&B of Georgie Fame, through the jazz and the rock and the less obvious categories of music that you've explored over the years. How do you see the music on this record?

RR:

I do see it as a true fusion of my music. It's always difficult when people want to call you this, that or the other, but I've always played different kinds of music. For me, there's never been a border line between jazz and pop; it's all to do with what you give to the song and what energy you put in. I was brought up in the rock 'n' roll era and then listened to jazz players, so that's always been part of my music. This album does represent some of these different facets, and to get it together compositionally was a test, really. That's why it took a while. For example, "Way Back Now" I rewrote four or five times to get it how I wanted it to sound.

I do see it as a true fusion of my music. It's always difficult when people want to call you this, that or the other, but I've always played different kinds of music. For me, there's never been a border line between jazz and pop; it's all to do with what you give to the song and what energy you put in. I was brought up in the rock 'n' roll era and then listened to jazz players, so that's always been part of my music. This album does represent some of these different facets, and to get it together compositionally was a test, really. That's why it took a while. For example, "Way Back Now" I rewrote four or five times to get it how I wanted it to sound. AAJ: The track that opens the record, "The Island," goes through quite a few changes stylistically. Was that a difficult one to bring together?

RR: I wrote that for Gary [Husband] because he's very good at dropping into a half time or a different approach in the same tempo. I developed it from things we do live; I would develop a riff, and he would play over it. When the track goes into the R&B section, it's fun. It's just a way of playing with time.

AAJ: Your son, George Baldwin, plays on this track. Is this the first time you've recorded together?

RR: He's played gigs with me, but we haven't recorded on an album together. It was a thrill. He sounds really good. Gary likes playing with him, so I thought he should really play on this track. It's quite a difficult track in some ways, but I think he nailed it.

AAJ: He really does. Ray, Now, More than Ever comes seven or so years after Goodbye Svengali (Cuneiform, 2006). Why was there such a large gap between the two recordings?

RR: It is a while. It's amazing. I'm afraid time passes. I was doing more TV music and gigs. I was toying with ideas on and off for ages, but I don't really see the point in recording an album just because six months have gone by. That album, Goodbye Svengali, was more reflective; it was a tribute to Gil Evans. I've turned into a hooligan in my old age. I've turned back to the days of rock, and I kind of like it. Hence, Now, More than Ever is more outgoing.

AAJ: You've spent a lot of the past 30 years composing award-winning music for television and film. Is this a form of music-making that you get a lot of satisfaction from, or is it, to evoke a phrase, the day job?

RR: [Laughs] I really enjoy doing it. I really enjoy being part of that illusion. It's a different way of expressing yourself. If people come out whistling the theme, because they can't come out whistling the special effects, you've done your job. That's what I try to do with the TV music.

It's another dimension, another language. You're telling a story that runs alongside the visuals. It ranges from the melodic to chase sequences or more atmospheric sequences. Once you've seen the picture, you can't really disconnect the music from the picture.

AAJ: Now, More than Ever is out on the Abstract Logix label. How did you come to be on Souvik Dutta's label?

RR: I wanted to be on this label because there are so many great musicians on this label, especially guitar players. I thought it would be a great label for the album. I made contact with him and asked him if I could send him some music to see what he thinks. He loved it and said, "Yeah, we'll do it." It was really as simple as that. It was just like the old days where you could call people up, and they answered the phone. I sent him the masters, the info and the pictures, and he put it out. I can't praise Souvik enough for being such a great music fan.

AAJ: It sounds great, like all the releases on Abstract Logix. On Now, More than Ever, you've surrounded yourself with a lot of familiar faces and long-term collaborators. Was it a no-brainer to bring in people like Gary Husband, Mo Foster, Jimmy Johnson and Anthony Jackson?

RR: Yeah, a no-brainer, indeed. I wanted to have my favorite musicians, and I've played with everybody. I hadn't played with Anthony for a few years, and I kind of pined for his playing. Jimmy, too. I missed them, and it was an opportunity to get them on my record. Anthony was in London playing Ronnie Scotts with [pianist] Hiromi, and so I booked some studio time. With Jimmy, I sent him the files, and he sent his bass parts back—a phenomenon of the modern age. It's an honor to play with these guys. They all have a sonic signature, and to me this album is about that. You know who everybody is immediately from their playing.

AAJ: In an ideal world, would you have had the same three or four musicians on every track, or did you write with specific musicians in mind for each composition?

RR: Yeah, I had people in mind for specific tracks. For example, "Way Back Now" with Anthony—I knew it would be up his street. I knew he would nail that riff. The tracks were purposely built for the musicians.

AAJ: With Abstract Logix, you're on the same label now as guitarist John McLaughlin. Did you run across each other much in your London session-musician days in the 1960s?

RR: Well, one of my first gigs was with Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, and I took over from John. The story is that I was at one of my first-ever sessions—I wasn't fully on the scene. It was at Lansdowne Studios, one of many studios that have gone now, but a lot of sessions were done there. There were three guitar players on the session; one was John, there was me, and the other was Jimmy Page. John asked if we'd like to play with Georgie and join the band because he was going to America. Jimmy said he was going to get out of playing sessions to form a band with Robert Plant.

That was that session, so you know what happened there. There was John going off to play with Miles Davis, and there's Jimmy going off to form Led Zeppelin. He didn't know it was called that then.

AAJ: It was The New Yardbirds first, wasn't it?

RR: The New Yardbirds, that's right. So I met up with Georgie and John at Ken Colyer's place, Studio 51, and in the middle of our jam together, to make sure we got on, [promoter] Chas Chandler came down and said, "I've got this guy I want you to hear. He sounds great," and in walked [guitarist] Jimi Hendrix. He borrowed our gear and played for five or ten minutes. It was a very strange chain of events. It didn't mean much at the time, but when you look back on it, it was one of those extraordinary things that used to happen in those days.

AAJ:. The birth of Davis' In a Silent Way band and the birth of Led Zeppelin at around the same time got you the gig with Georgie Fame. And in walked Jimi Hendrix. What an amazing situation!

RR: Wasn't it? It was an important moment.

AAJ: They seemed like such extraordinary times.

RR: They were extraordinary. One of my first gigs was with [singer/songwriter] Cat Stevens. We did a tour of Sweden where Cat Stevens was headlining, and Jimi [Hendrix] was the support band. Of course, we all used to watch Jimi, and he was fantastic. It was outrageous. I remember one time, somewhere in Sweden, I was lying in my bed trying to get to sleep, and Jimi was knocking on my window, which obviously was on the ground floor. He'd got locked out. I let him in, and we had a cup of tea and chatted about music for 10 minutes, and then he went to bed. It doesn't mean much, but it's strange that that sort of thing would happen then.

AAJ: It seems even stranger that Jimi Hendrix would be opening for Cat Stevens. Once you've seen Hendrix, surely Stevens would seem a little tame by comparison, no? From "Hear My Train a Comin'" to "Morning Has Broken."

RR: Yeah. But the thing is Cat Stevens had a big fan base, and while people were probably blown away by Jimi they probably didn't come to see him. In those days, there could be all sorts of different bands on the same bill. It was interesting. They used to give people a chance. Jimi probably made quite a few thousand fans in Sweden on that tour.

AAJ: What year was that?

RR: I can't remember exactly, but it was the year Cat Stevens had "I Love My Dog" out.

AAJ: 1967, his first album. Were you involved much with the Little Theater Club in London in those days?

RR: Oh, that's interesting. [Drummer] John Stevens and that crowd. Yeah, I played a few gigs there. I did a couple of broadcasts with [bassist] Dave Holland. That was my little quartet. Also [bassist] Ron Matthewson and Alan Rushton and a pianist who died quite a few years ago called Roy Fry. I was quite involved in the free-jazz scene for a while. I really enjoyed it because I learned a lot about music. Although it was a much-maligned music, I think there was a lot to it. When [saxophonist] John Coltrane played in a freer way, he brought a lot of people into it.

AAJ: Was American jazz still the main reference, or was there an identifiable British sound back then?

RR: There were great British musicians, but I was listening more to the American stuff—Coltrane, [saxophonists] Archie Shepp and Pharoah Sanders. Sometimes some of the European stuff left me a little bit cold. The Americans were just saying something that I related to more.

AAJ:

Your debut record as leader, Turn Circle (CBS Realm, 1968) was followed by a clutch of critically acclaimed jazz albums like Dragon Hill (CBS Realm, 1969) and Rites and Rituals (CBS Realm, 1971). What are your abiding memories of those days?

Your debut record as leader, Turn Circle (CBS Realm, 1968) was followed by a clutch of critically acclaimed jazz albums like Dragon Hill (CBS Realm, 1969) and Rites and Rituals (CBS Realm, 1971). What are your abiding memories of those days? RR: Things used to go very quickly. We did a lot of gigs. CBS, which those records were on, was great because it brought my music to a lot of people. It was a big learning curve for me. I played with a lot of great musicians, and I felt I was really growing up, musically. I also had a band called Rock Workshop, which was on CBS as well. It was one of the first fusion/prog-rock bands. CBS wanted to get a band together that would equal Blood, Sweat and Tears, and although we did get into the charts with one of our numbers, though not very high up, we weren't quite what CBS had in mind because the music got more outrageous [laughs]. It was a real fusion of rocky R&B and free jazz.

AAJ: How would you compare playing and recording jazz today compared with 40 years ago?

RR: That's a good question, actually. It's so difficult to use the word "jazz" now. I call it improvised music because people's idea of what jazz is has totally changed. There's even something called dinner jazz now—music to eat by. I think people don't want music served up in defined categories. I think Whitney Balliett wrote about "the sound of surprise," and I think that's what a lot of people want.

AAJ: You were also briefly in the band Nucleus in the early 1970s, and thanks to Cuneiform, your time in Nucleus was recorded for posterity on the Live in Bremen CD (Cuneiform, 2003). How did it sound to your ears, 30 years on?

RR: They were just live two-track tapes [laughs], and sound-wise there's obviously a lot lacking. What I do like about it is the chemistry is there. It was a good live gig. People who want to hear that music will forgive the sound quality, even in this high-tech day and age. It was an organic happening that somebody happened to record, and it came out years later. I find that fascinating.

AAJ: Was there any chance that you might have continued to play with Nucleus? Would that have appealed to you?

RR: Yeah, but it was difficult at the time because I was doing a lot of different things. I was in about four or five different bands, and they were doing a lot of touring, so I couldn't have. But I probably would have if I could. Obviously, it was a great band, but it went through a lot of phases. At that time, I would say Nucleus was near to Soft Machine, in a way. I was happy to be in Nucleus in the era I was, because perhaps other eras of the band I wouldn't have been into so much. I did really enjoy my time with them.

AAJ: Some of you solo albums have been rereleased in recent years on the Angel Air label, like Childscape (Theta, 1987), which came out as Why Not Now (Angel Air, 2004). Is it important to you to make all your older music available in modern formats?

RR: It wasn't foremost in my mind, but it's great that there are people like Peter Purnell at Angel Air who spend the time and effort putting out music that isn't necessarily a guaranteed financial success. Peter has made it his business to reissue music that he thinks is worth listening to. Had it not come out, I don't think I would have bothered to do it, but I am very glad it is out. Early albums, like Running Man, he put out on vinyl, and funnily enough it did quite well in Japan. It pleasantly surprises me who buys these things. But I'm also very pleased that Angel's Air puts out a lot of people's music. More power to Peter; I think it's an example that a lot of bigger, more corporate labels should follow.

AAJ: Does it ever cross your mind that one day old music on vinyl that isn't digitalized may become lost with time?

RR: Yeah. There's that saying that when someone dies, it's like losing a library. I also think that there are a lot of people who should be interviewed about their life but aren't, maybe just because they aren't overtly famous. They should be interviewed and recorded visually to record the social history of music. With regard to the vinyl, luckily in my case I think it's all been reissued on CD and some of it digitally, which is great. It's all out there.

AAJ: Coming back to Now, More than Ever, what guitar effects do you use?

RR: I wanted to have a really natural guitar sound without using too many effects. Gear-wise, I use a '54 Strat Relic. It's not an original '54; it's rebuilt, and I'm using a Bogner amp. The effects are just some delay, and I use a loop station on some of the solos—a live loop. I use a reverse effect on a Line 6 pedal, and that's about it. I also used Ebow. The thing about effects, like with Ebow and reverse echo, it only has to be a bit juicy, and it makes the music sound very mysterious- -much more so than it is. The Ebow is so wacky and so off the wall. It appealed to me as soon as it came out. But the main thing about this album is the basic sound of the guitar.

AAJ: Of modern guitarists, who do you like with regard to the manipulation of sound?

RR: Guitar players with sound? Very interesting. Somebody I've always liked is David Torn. I always thought he has a great integrity with sound. I like John [McLaughlin] a lot, although he's not very experimental. I just really like his sound. And John Coltrane, he had a very beautiful sound. I think guitarists should aim for a good basic sound and then think about enhancing it.

AAJ: Although you're probably best known for your more volatile playing, there's a whole other side to you, as evident in the ballad "Now They Are Gone" and "Cab in the Rain." Who has influenced you on the more balladic/melodic music you play?

RR: I've been very influenced by [pianists] Bill Evans and Lyle Mays, and a lot of Herbie Hancock's ballads. "Now They're Gone" is really about the people who have passed on and joined the upstairs orchestra. They suddenly aren't with us anymore, and this was the inspiration for that song. It's slightly into the orchestral realm, which I like. The effects on that were just whammy bar, reverse echo and a lot of finger modulation. I'm able to extend the emotional range, as it were.

AAJ: You've also recorded and performed with a tremendous number of pop stars over the years. Has playing with a wide variety of artists taught you much about producing and handling musicians' egos?

RR: [Laughs] with egos, what I think it's really down to is respect. Everybody wants to do well and wants to be heard, but I've never really had a problem. With a session, you probably meet 10 or 15 different people, each with an agenda going on, and you just try to help them to get the desired effect. As a session musician, you're playing for the song. You want that music to be as good as it can be.

An example of that in the commercial realm would be Heaven 17, who at the time were recording the album What Men Are (Virgin Records, 1984). They had the songs in bits. They were one of the first bands I knew to use a Fairlight, a very old-fashioned sequencer to try and put things in order. I came in and just did a lot of riffs that they liked, and it kind of became intro and middle. Someone said to me later, "You kind of co-wrote those," and I thought you could look at it that way, but as a session musician that's what's required of you. You don't come away thinking, "Hey, I wrote that"; you come away thinking, "I added to that track." It became a hit because of what everybody did. I never say a hit was down to me, because it's never down to one person. But it's great to be part of it.

AAJ: Did you play on David Bowie's "Space Oddity"?

RR: The story there is that John Worth did some charts for "Space Oddity," and they wanted acoustic guitar. I have to be honest, I'm told I'm on it, but I was never credited. With the James Bond stuff, a lot of the music I did on "Live and Let Die" (1973) is credited to someone else on a couple of websites. That's just how it is, so I'm always as careful as I can be about what I did and didn't do.

I had a band when I was about 12, maybe younger, and we did support to a band called Davey Jones' Locker, which was very early Bowie. Don't ask me how that gig came about [laughs].

AAJ: Another band that was really significant in Northern Ireland in the 1970s was the Celtic rock band Horslips, for which you arranged brass on the album Dancehall Sweethearts (Oats/RCA, 1974). Was that one of your earliest ventures into arranging for other bands?

RR: Yeah, it was. That was courtesy of producer Alan O'Duffy, a lovely guy who I still see occasionally. I really enjoyed that session. They were really great guys and a great band. They were all living in a house in Victoria, and we used to gather to discuss the tracks, and we'd always make an evening of it. Why take an hour when you can do it in six [laughs]? It was great fun.

AAJ: You went on to play with one of the great modern arrangers, Gil Evans, who inspired your own recording Goodbye Svengali. How did that collaboration come about, and what was the experience of working with him like?

RR: It came about because trombonist Malcolm Griffiths told me Gil was coming to London and putting together a band, and he asked me if I'd like to do it. I didn't have to think too long about that one. I think Gil had a soft spot for guitar players- -he used to play with the late Hiram Bullock. And we just hit it off. I took him to see some English folklore things, like the Vale of White Horse and Stonehenge, which he'd never seen.

Obviously whenever we went out somewhere together, we used to talk about music a lot. I remember one time we were in an Indian restaurant, and he was talking about Sketches of Spain (Columbia, 1960). I asked him about how he'd voiced something, and he wrote the stave out on this serviette and wrote the voicing out. I thought, "Fantastic, I'll have to keep that." Then the waiter came, picked up the serviette, put a plate on top of it, and away he went. I had in my mind I was going to frame that serviette. Gil actually threw away a lot of his old scores because they were taking up room in his house.

Gil was like a spiritual father figure to me. It was Zen and the Art of Jazz. He had this Zen attitude towards playing. One of the first times we met, there were about 15 of us in the big band, and he had about four sheets of manuscript paper, and he was meticulously tearing up the manuscript paper into one-stave pieces. This struck me as strange behavior, so I watched it. He wrote a different note on everybody's paper—one semibreve note. He gave everyone their note, and he said, "This is your note; if you don't like it, you can always change it" [laughs]. I thought, "Fantastic, so this is how it's going to be."

I was also lucky, I should say honored, to play all the scores he wrote for The Gil Evans Orchestra Plays the Music of Jimi Hendrix (RCA Victor, 1975). Unfortunately, he died a short time before the album. It was a life-changing experience working with Gil. You talk about handling musicians; Gil had this fantastic way of making suggestions just by a look or a nod or by just playing a certain note. He'd come on and start playing piano, and the whole set would be carried along by a few nudges he made on piano—without any words at all from beginning to end, just music. That was very interesting.

AAJ: Are there plans to tour with this CD?

RR: I have every intention of touring and doing a many gigs as possible, but at the moment no dates have been sorted. I can't confirm anything, but the answer is yes. Hopefully, we'll play in Europe, too. I'm really looking forward to it.

AAJ: What are you working on at the moment?

RR: A couple of things writing-wise. One is the music for a documentary called "The Walk," which is about the pilgrimage to Santiago. I've also done the music for a film called "Northern Soul," which is about the phenomenon of Northern Soul that went on—the soul music and R&B—in Blackburn and Manchester and the northern towns. It was like an early rave culture. I'm also doing some more writing for another album.

AAJ: Is there a special significance behind the title Now, More than Ever?

RR: Yeah. It's really a call to arms. We need to be aware and involved. It's to do with being aware of social values, which we should be. The change has to come from within ourselves. Now, more than ever, we need to take stock of past, present and future. It's just saying, "Be positive."

AAJ: Do you feel you're in a good place musically now?

RR: Yeah, I do. With your own work, there's always a tendency to think, "Maybe I could have done this better, and maybe I could I have written that better," but I think the CD achieved its objectives of bringing past influences together and making them all fit musically. Everybody interacts with everybody else, and that's the whole premise of the music. That's the magic of it. I'm happy with it. I think it's a concise statement of where I'm at, and I do feel I'm in a good place. I feel very positive about playing. It's fun, which is how it should be.

Selected Discography

Ray Russell, Now, More than Ever (Abstract Logix, 2013)

Ray Russell, Goodbye Svengali (Cuneiform Records, 2006)

Nucleus, Live in Bremen (Cuneiform, 2003)

Ray Russell, Why Not Now (Angel Air, 2004)

Simon Phillips, Symbiosis (Lipstick, 1997)

Ray Russell, A Table Near the Band (Virgin, 1990)

Gil Evans, Take Me to the Sun (LCM, 1990)

Ray Russell, This Side Up (B&W Records, 1989)

Mo Foster, Bel Assis (Angel Air, 1988)

Scott Walker, Climate of Hunter (Virgin, 1984)

RMS, Centennial Park (Angel Air, 1982)

Judie Tzuke, Welcome to the Cruise (Rocket, 1979)

George Melly, Melly's at it Again (Reprise Records, 1976)

Ray Russell, Secret Asylum (Black Lion, 1973)

Ray Russell, Rites and Rituals (CBS Realm, 1971)

Rock Workshop, Rock Workshop (CBS, 1970)

Ray Russell, Dragon Hill (CBS Realm, 1969)

Ray Russell Quartet, Turn Circle (CBS Realm, 1968)

Photo Credits

Page 1-2: Ron Baker Ashton

Page 5: Sally Howard

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.