Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Marcus Belgrave: Preserver of Jazz

Marcus Belgrave: Preserver of Jazz

In talking with Belgrave before taking the stage at this year's Detroit Jazz Festival, I not only learned how "Detroit saved his life"—from his work with the Ray Charles Orchestra to ultimately becoming a staff trumpeter at Motown Records in its prime—but as he continues to educate other aspiring musicians, it reassured me that perhaps this music will not die with him and the other great figures who helped to create it.

All About Jazz: Did you come from a musical background growing up?

Marcus Belgrave: I definitely came from a musical background. I grew up in a town called Chester, Pennsylvania, right outside of Philadelphia where all the big hitters are. [Laughs] It's a very lively music town [where] every major musical entity of the 1940s and 1950s came through that town because of the Second World War. Chester built battleships for the war. So it was a very happening town back [then]—I was born in 1936. It seemed like everyone had a piano or an instrument in their house in those days, especially a piano because it kept the spirits alive. The musical environment was definitely a part of my growing up.

AAJ: When did you ultimately decide to become a jazz trumpeter?

MB: Well that was in my blood from the very beginning. Cecil Payne, my cousin, was an alto and baritone saxophone player. He played with the Dizzy Gillespie Band. They used to rehearse at Cecil's house in Brooklyn. Ultimately I was around the music when I was three or four, so I heard it from the real thing. It inspired me. Dizzy Gillespie was my first idol and then of course Miles [Davis]. My father played the bugle in the Second World War and he taught me all the bugle calls when I was like four years old. So I had a natural matriculation to the trumpet at six. He bought me a trumpet at six-and-a-half for Christmas and it's been my instrument ever since.

AAJ: Another one of your early mentors was the late Clifford Brown. Please talk about your experience in studying with him.

MB: He was one of my main mentors. I had the privilege of sitting next to him in my [concert] band when I was 12 years old. I learned a lot just being close to him. He took a liking to me even in those days. [He was] part of the reason why I decided to come to Detroit. I had heard that there was a guy in Detroit that could play rings around Clifford. [Laughs] The person that I'm talking about was Thad Jones. But that's another reason why I came to Detroit—I wanted to see what was in the water. [Laughs] As far as I was concerned, Clifford was a major era [for me]. The main thing that I learned is that you take this music very serious. When you think of [jazz], you think of it as being something special and set aside, which is, but it's still music. So talking to Clifford on many occasions, he has impressed upon me that probably I should play all kinds of music. After hearing people like Dizzy and Miles and then Clifford, it was very easy for me to make a transition to Louis Armstrong. There's a direct lineage from all the trumpet players. Sometimes I used to wonder "where am I going to fit in." [When] my peers—Freddie Hubbard, Lee Morgan, Booker Little —came on, there I was again wondering "where do I fit in." Johnny Coles, my god, was second person that made me cry. Even James Moody. Back in those days, being around those kinds of guys, you turned out to be inspired and just enamored by what they did.

MB: He was one of my main mentors. I had the privilege of sitting next to him in my [concert] band when I was 12 years old. I learned a lot just being close to him. He took a liking to me even in those days. [He was] part of the reason why I decided to come to Detroit. I had heard that there was a guy in Detroit that could play rings around Clifford. [Laughs] The person that I'm talking about was Thad Jones. But that's another reason why I came to Detroit—I wanted to see what was in the water. [Laughs] As far as I was concerned, Clifford was a major era [for me]. The main thing that I learned is that you take this music very serious. When you think of [jazz], you think of it as being something special and set aside, which is, but it's still music. So talking to Clifford on many occasions, he has impressed upon me that probably I should play all kinds of music. After hearing people like Dizzy and Miles and then Clifford, it was very easy for me to make a transition to Louis Armstrong. There's a direct lineage from all the trumpet players. Sometimes I used to wonder "where am I going to fit in." [When] my peers—Freddie Hubbard, Lee Morgan, Booker Little —came on, there I was again wondering "where do I fit in." Johnny Coles, my god, was second person that made me cry. Even James Moody. Back in those days, being around those kinds of guys, you turned out to be inspired and just enamored by what they did.AAJ: Please talk about your tenure with the Ray Charles Orchestra. When did you first meet Ray Charles?

MB: I met Ray Charles in Wichita Falls, Texas. That's when he was coming through there after I had gotten out of the service —I was in the Air Force. I waited for him for three weeks. So I had a chance to sit in with them, but I didn't get the job then. And then three months later, they came through my hometown. I ran into them in November in Texas, and [by the] end of January, they came and played at a place called The Harlem Club in Chester. The Raelettes joined the band about a month before me so I was the new young boy in the band in 1958. And Ray latched on to me—he loved me, loved the way I sounded.

And we had a nice run. I was with the Ray Charles Orchestra for five years. At that time, it was a small (seven-piece) band, before he got the big band. It was a hard job because we did a lot of traveling. I mean we traveled 500 to 600 miles a night—all one- nighters. So that was the hard part about it. But the glorious part is that I learned that Ray had a system of dealing with people. He could reach out and stretch your imagination. And then the way he played, he would pick the people the same way. So that amazed me and in my fastidiousness, I've tried to approach music the same way. I've tried to reach out to the public without denying myself. Ray featured me on a Ralph Burns [arrangement] called "Alexander's Ragtime Band" in his first big band album. It's on a recording called The Genius of Ray Charles (Atlantic, 1959), which featured several members of a three-band combination. He had members from the Duke Ellington Band, the Count Basie [Orchestra] and his band, the small band. "Alexander's Ragtime Band" was one that he featured mainly me, which kind of made me famous with trumpet players. I'm one of the last living members of the Ray Charles original small band. I really learned so much from Ray and I'm very happy for the time that he gave me.

AAJ: At what time in your career did you move to Detroit?

MB: I came to Detroit to save my life [and] get away from New York. [Laughs] New York was moving kind of fast for me in those days. I did a whole year with Ray Charles, but I got disenchanted, came to New York and stayed from 1959 to 1961, and then went back to Ray. So when Ray was ready to go back to work in 1963, I decided to stay in Detroit.

AAJ: Why did you decide to remain in Detroit?

MB: When I left Ray doing 600 miles a night, I was able to sit there in Detroit, make more money working at Motown and be home every night, so that was a revelation. It's probably one of the reasons why I'm still there. I was running up and down that road so much. Also, it allowed me to meet a gentleman by the name of Harold McKinney, who was a fantastic pianist. He was one of the only ones from Detroit during that time [that] didn't leave. Most of the guys left. There was a big exodus from Detroit in 1958 and 1959. A lot of really great musicians moved to New York. In fact, that's where I lived. I was inspired by a gentleman who told me if you don't make it in this business you might as well live in Detroit. Now I don't know why he said that but that was on my mind also because all the great jazz musicians I knew were from Detroit—Hank Jones, Tommy Flanagan, Charles McPherson. and Lonnie Hillyer came to New York about a couple of months after I did. And fortunately they got to play with Charles Mingus.

[Harold] McKinney was working with lots of young musicians. He worked with a group called The Six Lads. He trained these young gentlemen and they became like the toast of the town. So I picked it up from Harold, working with young people. He had gotten sick in 1970 and I didn't know what I was going to do. Harold had a program called Metropolitan Arts, a [federally funded] project in the inner city that fostered the development of young artists as well as took care of the old folks. It was like a program to revitalize a certain area within Detroit. That was an opportunity for me to test my teaching skills. So I got into the educational aspect of this music, trying to keep jazz alive.

AAJ: Please tell us about your work with Motown Records.

MB: The executive secretary to the first black radio stations to play black music 24 hours, WCHB and WDET, encouraged me to come here. And she was very close with Berry Gordy, so she introduced me to him at the end of 1962. They had the same capacity for that small group sound that Ray Charles had, however, they elevated to a big band as well. It was a natural thing for us to be in the studio with producers. So we would bring the musicians in the studio. They had three trumpets, two saxophones and two trombones. And then the rhythm section, who became The Funk Brothers; Johnny Griffith, Earl Van Dyke, The Williams/Roberti/White Trio and Eddie Willis were the guitar players; (bassist) James Jamerson and drummer Benny Benjamin. So that was the foundation of "The Motown Sound." A lot of bands around that same time had that similar combination like Jerry "The Iceman" Butler and Bobby Blue Bland. With Berry, I wasn't as close with him. I was close with the artists—The Four Tops, The Temptations and Mary Wells. I left before Diana [Ross] came to Motown. I would see her every day, but they hadn't formed [The Supremes] when I left in 1964, involuntarily when my father had gotten sick. So I took care of him until he passed, and then I came back to Detroit in 1967—a couple of days before the riots.

AAJ: There's quite a stellar list of jazz figures that you've trained, like violinist Regina Carter, pianist Geri Allen and saxophonist Kenny Garrett. How does it feel to know that you've helped create these newer voices in jazz today?

AAJ: There's quite a stellar list of jazz figures that you've trained, like violinist Regina Carter, pianist Geri Allen and saxophonist Kenny Garrett. How does it feel to know that you've helped create these newer voices in jazz today?MB: Geri Allen and (bassist) Marion Hayden were two of my first protégées. And we discovered another young lady by the name of [clarinetist] Elrita Dodds. Elrita was born on Eric Dolphy's birthday and Geri was born on my birthday [June 12th]. So it was a natural thing to be involved with those people because they had the same kind of symmetry. Kenny Garrett asked me more questions than the law allowed. [Laughs] Even when he was with Miles Davis, I said, "Kenny, you're with the greatest trumpeter in the world. Ask him." [Laughs] I've got a bunch of babies I'm working with tonight. I just got done talking with a group of them. One of them happens to be my son, who's turning 15 soon. He plays the clarinet and saxophone. He's working with a group of guys his age, maybe a couple of years older. They are the next breed. And I'm training them, showing them how to conduct themselves on the bandstand and how they should research the music that they play. Because they want to play everything, know what I mean? That's why Kenny, Geri and Regina are all so great, because they've been writing their own music. And that's one of the things I encourage most of all. If you want to be in this business, it's not just good enough to play; you've got to write.

AAJ: How do you balance the two roles of musician and educator today?

MB: I stopped playing in nightclubs in 1996. I couldn't take the smoking anymore. By 1998, I embarked on another situation to do a tribute to Louis Armstrong. So I ended up being able to play at concert halls instead of juke joints. So that was a great thing. And then my teaching career started at Oberlin in 1999. I had worked there until 2009. I'm kind of retired now. But my wife and I have a project called "Marcus and Joan" or "Joan and Marcus." And we travel all over the country. Right now, I've been doing a study on Horace Silver's music, which is going to be at the [2012 Detroit Jazz] festival; we're doing a tribute to him with Louis Hayes, who was his drummer, and [trombonist] Curtis Fuller, who's also a mainstay Detroiter. So my coming here to Detroit was lifesaving to me and I imagine uplifting to another couple of generations of great young musicians.

Selected Discography

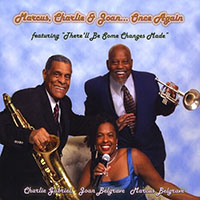

Marcus Belgrave / Charlie Gabriel / Joan Belgrave, Marcus, Charlie & Joan...Once Again (Detroit Jazzians Coop, 2009)

Marcus Belgrave, Tribute to Louis Armstrong (WJS, 2008)

Marcus Belgrave / Eddie Henderson / Javon Jackson / Ron Carter, Hub Art: A Celebration of the Music of Freddie Hubbard (Hip Bop, 1996)

Marcus Belgrave, Live at Kerrytown Concert House (Detroit Jazzians Coop / DJM Records, 1995)

Marcus Belgrave, Working Together (DJMC, 1992)

Marcus Belgrave, Gemini II (DJMC, 1975)

Marcus Belgrave, Gemini (Soul Jazz, 1974)

Ray Charles, The Genius of Ray Charles (Atlantic, 1959)

Photo Credits

All Photos: Clyde Stringer

Tags

Marcus Belgrave

Interview

Shannon J. Effinger

United States

Karriem Riggins

James Carter

Dizzy Gillespie

Cecil Payne

Clifford Brown

Motown

Thad Jones

Louis Armstrong

Freddie Hubbard

lee morgan

Booker Little

Johnny Coles

James Moody

duke ellington

Count Basie

Harold McKinney

Hank Jones

Tommy Flanagan

Charles McPherson

Lonnie Hillyer

Charles Mingus

The Funk Brothers

Robert White

James Jamerson

Jerry Butler

Bobby Blue Bland

The Temptations

Regina Carter

Geri Allen

Kenny Garrett

Marion Hayden

Eric Dolphy

Miles Davis

Louis Hayes

Curtis Fuller

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.