Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Sonny Rollins: Mark of Greatness

Sonny Rollins: Mark of Greatness

So it had to be a hell of a year for Sonny Rollins—had to be. But, with the ever level-headed, realistic and humble Rollins, one wouldn't really notice it. He doesn't classify 2011 as that special. Rollins sees it as a year when he continued to develop his music and—at times—reached satisfactory levels. That's not bad for the reigning king of jazz improvisation, who is notoriously hard on himself.

In December of 2011, Rollins was among five recipients of the Kennedy Center Honors, awarded annually for exemplary lifetime achievement in the performing arts. In March of 2011, Rollins was in Washington, D.C. to receive the National Medal of Arts from President Obama. Rollins, at 81, continues to play his horn with such passion, intensity and creativity that he also garners the highest praises in the jazz community. He regularly tops annual magazine polls. He was Musician of the Year and Tenor Saxophonist of the Year in 2011, as voted by the Jazz Journalists Association. Rollins' recording Road Shows, Vol. 2 (Doxy, 2011) is up for two Grammy awards in February, 2012.

The Kennedy Center Honors medal went to the jazz titan and four other honorees—Yo-Yo Ma, Meryl Streep, Neil Diamond and Barbara Cook—at a State Department dinner on December 3, 2011. There, Rollins was introduced by former President Bill Clinton and lauded by President Obama. The next day, there was a gala ceremony at the Kennedy Center, celebrating the winners. (It was televised a few weeks later on CBS television.)

But for Rollins, ever the vital artist, those were pleasantries. He is grateful for them, but he's living in today's moments. He's focused on right now, on trying to be the best person possible and to navigate through a changing and often caustic world. He's focused on his art—making meaningful music with that curved contraption of metal from which he coaxes warm, exotic, emotional, delectable sounds. Rollins has always graciously accepted the accolades that have come his way, and he knows his stature as jazz royalty. But he doesn't flaunt it—there is a huge dose of humility involved.

"Fun?" a bemused Rollins reflects, a few days after the prestigious Kennedy Center events. "Well, that wasn't exactly my style."

What's exciting him these days, as he rests while his 2012 tour schedule takes shape, is how his band sounds and its pursuit of something special: reaching for something extraordinary, something for today. And it's nothing mystical; it's out there and attainable. It's so much within reach that Rollins wants to make his first studio recording since Sonny Please (Doxy Records), in 2006. He feels that "something revelatory" can be captured—something much better than his Grammy-nominated album that doesn't really impress him.

"It's describable," says Rollins about the musical place he's trying to reach. On his 2011 tour—Road Shows Vol. 2 is 2010 music—the band was making progress toward that objective. "It's not that I'll know it when I hear it; I know what it is now. We just haven't been able to produce it. But it is producible, because we produced it in this last year, at certain times." That band was Peter Bernstein on guitar, Kobe Watkins on drums, Bob Cranshaw on bass and Sammy Figueroa on percussion.

"It's describable," says Rollins about the musical place he's trying to reach. On his 2011 tour—Road Shows Vol. 2 is 2010 music—the band was making progress toward that objective. "It's not that I'll know it when I hear it; I know what it is now. We just haven't been able to produce it. But it is producible, because we produced it in this last year, at certain times." That band was Peter Bernstein on guitar, Kobe Watkins on drums, Bob Cranshaw on bass and Sammy Figueroa on percussion."That's why I'm very interested in doing a studio album, if I can get it done before we go back on tour. ... The beautiful thing about this music and improvisation and jazz music that we try to play is that: OK, what I want to do, I know I can do—but when we do that, it leads to something else. It's not that I know what it is, and we'll do it, and that's the end. No. That's going to lead to another door opening, which is fine. But I haven't opened this door yet. That, I think we can do now in the studio. I haven't made a studio album in a while, either. I'd like to do one."

Rollins has been making revelatory music since his emergence on the New York City scene in the 1940s. He and John Coltrane are the most influential saxophonists in the post-Charlie Parker era. But his life has been more than that—it's been an example of perseverance and strength of character. His approach to life, as well as art, is exemplary. Every conversation with Rollins is valuable; that's rare.

"Music is of a certain place; jazz is of a certain place. Life is of a certain place now; the world is at a certain place now. Every day is something new. And music is in a certain place now. I think into that area of where the world is at. So that's what I haven't really gotten out, yet," says Rollins. "We've done it in our performances. This last tour in Europe was very successful. Commercially, it was very successful, but also it was musically successful, and we had some jobs leading up to that which were successful. So there's something I know we can accomplish musically, which I haven't been able to accomplish yet. I can't describe exactly what it is. But it's not some of the stuff which I played on Road Shows 2, on which I played a lot of standards. Sure, I might have played something different on them, but they were basically straightforward, except for the duo—or, as Bill Clinton called it [in his toast to Rollins at the Kennedy Center Honors dinner], 'a duel'—with Ornette Coleman. Other than that, it was very straightforward. I want to move beyond that. I mean, not to a point where people don't understand it. Not that—to the point of 2012, that's all. When I do that, I'll feel satisfied—more satisfied. The people will also be edified. Because I know what it is. The people, in some cases where they've gotten it, they've reacted, of course. So that's where I want to be, and that's what I haven't gotten out on records yet."

"Music is of a certain place; jazz is of a certain place. Life is of a certain place now; the world is at a certain place now. Every day is something new. And music is in a certain place now. I think into that area of where the world is at. So that's what I haven't really gotten out, yet," says Rollins. "We've done it in our performances. This last tour in Europe was very successful. Commercially, it was very successful, but also it was musically successful, and we had some jobs leading up to that which were successful. So there's something I know we can accomplish musically, which I haven't been able to accomplish yet. I can't describe exactly what it is. But it's not some of the stuff which I played on Road Shows 2, on which I played a lot of standards. Sure, I might have played something different on them, but they were basically straightforward, except for the duo—or, as Bill Clinton called it [in his toast to Rollins at the Kennedy Center Honors dinner], 'a duel'—with Ornette Coleman. Other than that, it was very straightforward. I want to move beyond that. I mean, not to a point where people don't understand it. Not that—to the point of 2012, that's all. When I do that, I'll feel satisfied—more satisfied. The people will also be edified. Because I know what it is. The people, in some cases where they've gotten it, they've reacted, of course. So that's where I want to be, and that's what I haven't gotten out on records yet."Some health issues have to be addressed for the octogenarian, but getting into the studio is important. "I had a hard year, so I have to sort of get some things straightened out, make sure I'm going to be OK to hit the trail again. Hopefully, that should be OK. Then I want to do [the recording] before I go to work in the spring," Rollins explains. "I have four new songs that we have been playing in performance. It's good to play these in performance. It shows where it can go, also. We've been doing that. So I know they will work, and I know we can do them and be successful. Four or five new songs that have never been recorded—that's definitely waiting to be recorded.

"I hope to produce some really revelatory music. I want to do something that I can really be happy with. That's what I mean about Road Shows 2. I didn't get on it what I wanted to. ... Besides the Ornette duet ["Sonnymoon for Two"], which was really adventurous, everything else was stuff I have done—the material, anyway. We can sound different every night on anything. But the material was stuff I could have done before. You know what I mean? ... That's why I'm glad Ornette came and we played together. Because that was a little bit different. Everything else besides that was playing which I could have done 25 years ago, or 40 years ago, or 50 years ago. In terms of format and material ... I had other material to put on there, but after listening to it, it wasn't what I wanted it to be."

With such high standards, it's got to be difficult for Rollins to reach a level of satisfaction. It's pressure that comes from his own exacting standard of what art, made in the moment, can be. Opening that saxophone case and reaching for the horn—yet again—brings an element of the unknown. But the horn is also like an appendage.

With such high standards, it's got to be difficult for Rollins to reach a level of satisfaction. It's pressure that comes from his own exacting standard of what art, made in the moment, can be. Opening that saxophone case and reaching for the horn—yet again—brings an element of the unknown. But the horn is also like an appendage."It's not so much: 'There it is again,' because it's such a part of me now—almost [like] going to the bathroom or something. You have to go again, but you don't think about it in that sense. It's such a natural part of your life, you don't think of it as something separate from your everyday existence," Rollins says. "There are some instances where I might not practice for two or three days, for whatever reason. I don't mean when I'm traveling. When I'm traveling, I have to be off. I can't practice two or three days. But when I'm at home and for some reason I can't practice for two or three days, I begin to feel physically out of sorts. Then when I practice—bang, I'm back to normal."

Back to "normal" for Rollins is a different plateau—one that other horn players aspire to reach. Rollins doesn't feel it that way. He's on his own journey, and the search is what drives him. "Because there's more there, I'm searching not as a chaotic adventure. There's more there; this is what's important. There's more to be done in music. I'm a very fortunate person because I didn't start out at the top of my game. I started out as a youngster playing with a lot of guys who were much my senior and had a lot more experience than me. I was sort of a prodigy with all those guys I began playing with: people like Bud Powell and Miles and Thelonious Monk and all these guys. They were older than me and had much more experience. In a sense, I was lucky because my craft wasn't formed then. So I've been crafting my art form ever since. And I'm still doing that. It's a continuous thing; I'm still in that. I'm still kind of learning different things, musically. By playing with great guys, I realize how much music there is that I can do, that I'm not doing yet. It's a real thing to me. It's something that I have to do. I realize that it's part of the task of my life to try to get this thing right."

This is all done in an atmosphere that has changed drastically since the bebop and big-band years. In the United States, jazz took a back seat to rock-and-roll music, and pop music was influenced by that, rather than jazz. Pursuing any of the arts in the U.S. can be precarious. Rollins feels that jazz—beloved around the globe—needs more of a boost from the government in the country where it was born.

"When you're a musician, they don't want to pay you and all this stuff because they think you're having fun doing stuff. In a sense, that's right, but you've got to eat, too," he says. "Musicians and painters—they're human beings, too. They have to have a life and support families, et cetera. You have to have governmental intervention in order to preserve these things which are of such immense cultural value to the nation, to a populace. We need government to be involved. I'm sorry, Tea Party, but we need the government sometimes."

On his two visits to the White House, Rollins came away with the impression that the President "is a brilliant guy," but as far as the music, he's more impressed with First Lady Michelle Obama. He learned that "her father and grandfather were both jazz fans. They had jazz playing all day. So Michelle knows all about it. I told her, 'That's great. It didn't impede you in any way, did it?'"

The Kennedy Center Honor for Rollins stands as one avenue of bringing the art form into the public eye. On the CBS broadcast—as Rollins sat in the balcony, looking resplendent with the other honorees—Joe Lovano, Ravi Coltrane, Jimmy Heath and others got to perform, albeit briefly. But jazz got some bright moments, and perhaps some Americans got enlightened.

In the latter part of 2011, Rollins' band did a European tour. "We were in Budapest, in Istanbul, in France, Germany. There are people there that love music, that love jazz," he says, explaining that jazz has support all over the globe. "Things change. We have to admit that. But is jazz still relevant? Yes. It still has its audience. We need to support it. Classical music—that's supported by this government. People don't go out and buy classical music like they would buy some kind of pop music. ... Classical music has to be supported by the government. They have to subsidize some of these concert halls and things. They're subsidizing this music because they realize it's a cultural necessity to have this music. It's important [that] people have something like this—the same for jazz. I think [for] jazz, maybe a little more ... it's getting to be more like classical in that it needs more help from the government."

Every once in a while, the word "jazz" comes up for some debate in its own community. Some still feel it is a debasing term, at worst—a limiting term. But all music has labels, and most jazz musicians feel that it works: that it's a necessary label, if nothing else. Rollins can see both sides. "I don't necessarily see that it might be the best definition of the music. But it's there." He adds with a faint laugh, "Maybe it would make people think about it more if there was a big campaign to change it from 'jazz.'

Every once in a while, the word "jazz" comes up for some debate in its own community. Some still feel it is a debasing term, at worst—a limiting term. But all music has labels, and most jazz musicians feel that it works: that it's a necessary label, if nothing else. Rollins can see both sides. "I don't necessarily see that it might be the best definition of the music. But it's there." He adds with a faint laugh, "Maybe it would make people think about it more if there was a big campaign to change it from 'jazz.'"Mingus used to be a big guy that was against the use of the word 'jazz.' Yusef Lateef hated that word, 'jazz.' I did see why, because it really didn't mean anything, but it sort of ... There are so many other battles to fight. I think I would agree if you could wave a magic wand and we could change it into American music, or something like that, overnight with a wand. Yeah. But how could that happen? So I accepted it. But I believe that it's not the best word."

This jazz, this improvisational music, this American classical music, is vital and strong. Like everything, it can have its rough times, but it can never be squelched. "I feel there are a lot of young guys out there that can play," says Rollins. "Plus, jazz's introduction into the university has also produced a lot of very gifted young players. The jazz schools are burgeoning. The young guys—people like jazz. They love jazz. I don't know why the government is so slow to accept it. People love jazz in the United States, as well as around the world. But the problem with the United States not doing its part is that there are no places for jazz to be played. There are not enough venues. There should be afternoon concerts and TV shows with young jazz musicians. ... We need people in Washington that realize this is not only our gift to the world, but it's also important the musicians are taken care of. There are places where jazz can be played and appreciated: afternoon concerts, things like that—not just nightclubs. All sorts of other things are more respectable—places where jazz can be played and promulgated. That's what we need. Then people will like it. They'll hear more. It's important that people like it.

This jazz, this improvisational music, this American classical music, is vital and strong. Like everything, it can have its rough times, but it can never be squelched. "I feel there are a lot of young guys out there that can play," says Rollins. "Plus, jazz's introduction into the university has also produced a lot of very gifted young players. The jazz schools are burgeoning. The young guys—people like jazz. They love jazz. I don't know why the government is so slow to accept it. People love jazz in the United States, as well as around the world. But the problem with the United States not doing its part is that there are no places for jazz to be played. There are not enough venues. There should be afternoon concerts and TV shows with young jazz musicians. ... We need people in Washington that realize this is not only our gift to the world, but it's also important the musicians are taken care of. There are places where jazz can be played and appreciated: afternoon concerts, things like that—not just nightclubs. All sorts of other things are more respectable—places where jazz can be played and promulgated. That's what we need. Then people will like it. They'll hear more. It's important that people like it. "Jazz is a real art form. It's not something you can pick up and do in 10 minutes. You have to study it. It's great to study music. ... It's short-sighted and regressive thinking, which unfortunately exists in the world and exists in this country, and keeps jazz in the position where it keeps fighting to find a place to be heard. You've got to play in a nightclub and all the elements around a nightclub. But still, it survives. And when you go outside the United States you realize how much it survives."

Rollins, still the road warrior, continues moving forward, creating footprints that can be studied and followed forever, always valuable. "Make your way. Do the best you can. It's not long. It's a short life. Do the best you can, and we'll be ready for whatever happens," he reflects. "People tell me, 'Sonny, you believe in reincarnation.' I said, 'Look, I believe in reincarnation only because it seems to make sense.' But I'm not living my life for reincarnation, I'm living my life for now: this life, today. I'm trying to do right and be correct today—every day I live. Know what I mean? It has nothing to do with after you die. Heck with that. I'm living now and trying to right now. If that brings rewards, fine. It's bringing rewards for me now. So I'm ahead, anyway."

Selected Discography:

Sonny Rollins, Road Shows, Vol. 2 (Doxy, 2011)

Sonny Rollins, Road Shows, Vol. 1 (Doxy, 2008)

Sonny Rollins, Sonny Please (EmArcy/Doxy, 2006)

Sonny Rollins, Without a Song: The 9/11 Concert (Milestone , 2005)

Sonny Rollins, Global Warming (Milestone, 1998)

Sonny Rollins, The Solo Album (Milestone, 1985)

Sonny Rollins, Don't Stop the Carnival (Milestone, 1978)

Sonny Rollins, Nucleus (Milestone, 1975)

Sonny Rollins, East Broadway Rundown (Impulse, 1966)

Sonny Rollins, Alfie (Impulse, 1966)

Sonny Rollins, Sonny Meets Hawk (RCA, 1963)

Sonny Rollins, The Bridge (Bluebird, 1962)

Sonny Rollins, A Night at the Village Vanguard (Blue Note, 1957)

Sonny Rollins, Way Out West (Contemporary Records, 1957)

Thelonious Monk, Brilliant Corners (Riverside, 1957)

Sonny Rollins, Tenor Madness (Prestige, 1956)

Clifford Brown and Max Roach, At Basin Street (Polygram, 1956)

Sonny Rollins, Saxophone Colossus (Prestige, 1956)

Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins, Thelonious Monk/Sonny Rollins (Prestige, 1954)

Miles Davis, Bags' Groove (Prestige, 1954)

Sonny Rollins, Sonny Rollins Quartet (Prestige, 1951)

Miles Davis, Dig (Prestige, 1951)

Bud Powell, The Amazing Bud Powell (Blue Note, 1949)

Photo Credits

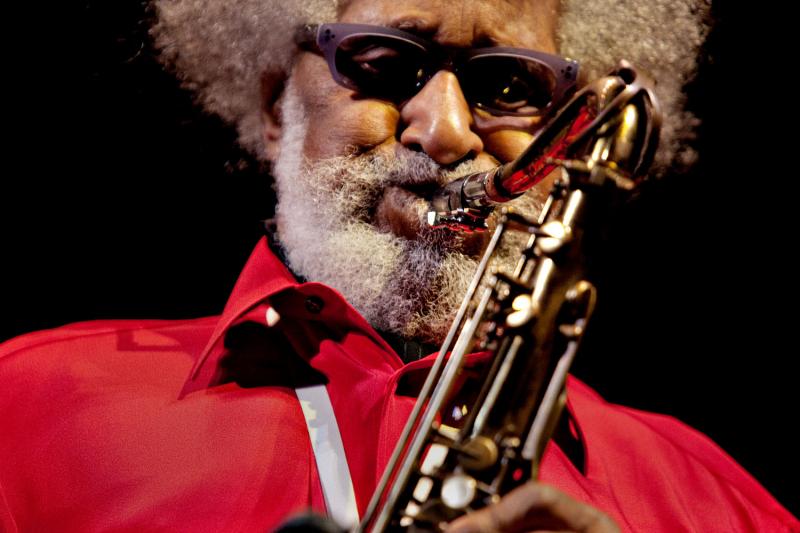

Page 1: Folkver Per

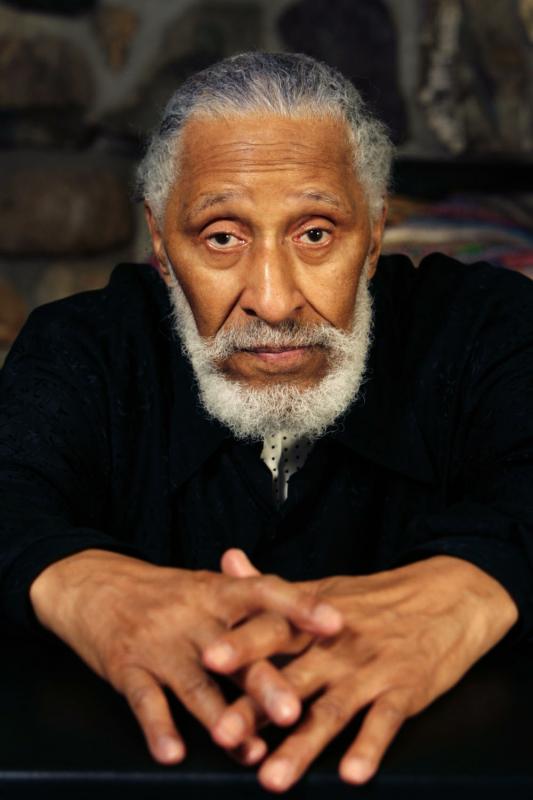

Page 2: Matthew J. Lee

Page 3: Kristoffer Juel Poulsen

Page 4: Seth Wenig

Tags

Sonny Rollins

Interview

R.J. DeLuke

Terri Hinte

United States

Peter Bernstein

Kobe Watkins

Bob Cranshaw

Sammy Figueroa

John Coltrane

Charlie Parker

Ornette Coleman

Bud Powell

Thelonious Monk

joe lovano

Ravi Coltrane

Jimmy Heath

Yusef Lateef

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.