Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Bill Frisell: Ramping It Up

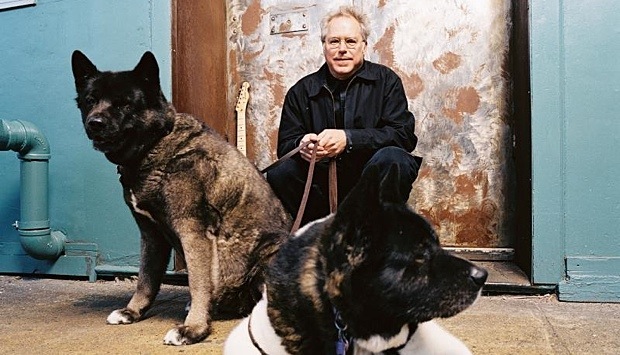

Bill Frisell: Ramping It Up

Courtesy Jimmy Katz

It's so personal and private, what a musician is really doing. I'm the only one who really knows what I'm trying to do. I could be doing something that's internally extremely difficult, and it could be something simple.

But even when it comes to commercial recordings released in hard media, with marketing pushes from labels like Nonesuch—the label that, until mid-2009, had been his home for 20 years—Frisell has found himself needing more than the usual one-per-year vehicle. With Beautiful Dreamers—a new project that Frisell wanted to record—and his near-decade-old 858 Quartet in need of putting some new music out in the world, Frisell faced a tough choice: stay with Nonesuch and live with one release each year, or dissolve the relationship. It had been Nonesuch that, after he'd established himself with the German ECM label in the early '80s, provided him the exposure and freedom to build his name and reputation as an artist ready to change directions—if not exactly on a whim, then certainly often to the surprise of those who'd just started to think they knew what he was about. Nonesuch, after all, has given Frisell an internationally distributed vehicle for everything from his mid-'90s sextet of remarkable compositional depth on This Land (1994) and the groundbreaking (and controversial) bluegrass/fusion music of Nashville (1996), to the unorthodox guitar/trumpet/trombone/viola of Quartet (1996) and the sample-driven music of the Grammy Award-winning Unspeakable (2004).

"It wasn't like any big thing," Frisell recalls about his decision to part ways with Nonesuch and hook up with Savoy Jazz. "We didn't have a fight, I'm totally on good terms, and I can't even believe how amazing that time with them was. The last thing I want to do is say they weren't coming through; it was just an extraordinary 20 years. I guess it's part of the nature of the times, but they just couldn't get the stuff out as fast as I was making it. It was a mutual decision; they just couldn't keep up with what I wanted to do, so we just agreed for me to try something else.

There were maybe a couple possibilities," Frisell continues. "I wasn't sure, at first, with Beautiful Dreamers. I had already booked a studio and was going to pay for it myself—I wanted to do it at that time because the music was ready, and I just didn't want to wait. And I would have put it out myself, but then Savoy just came along, and that was kind of a break for me. And right away, they also wanted to do the 858 thing, and that was really something—they're just six months apart [actually, seven: Beautiful Dreamers was released in August, 2010, and Sign of Life—Music for 858 Quartet in April, 2011]. That was kinda crazy. And it's a little early, and I hate to talk about things that haven't happened yet, but it looks like I'll do an album that's an expanded version of that John Lennon tribute, but it'll be with [bassist] Tony [Scherr] and [drummer] Pato Valdivieso, and I think we're gonna do that in the summertime [2011], so I think it's just bam, bam, bam. It's only been less than a year, but the kind of energy they're putting into it—it feels really good, and they really seem to care about it. I'm not Justin Bieber [laughs]; it's not the most accessible stuff, but they're really trying. I just don't know what's happening with the whole business of selling CDs, but it seems like they're doing everything they possibly can."

858 Quartet—a new spin on the classical string quartet, where one of the violins is replaced with Frisell's guitar, alongside Scheinman, violist Eyvind Kang and cellist Hank Roberts—has been around for some time, but it's only released one album to date, and while Richter 858 was made available to a larger audience by Canada's Songlines label in 2005, it was actually first issued as part of a limited-run book of artwork by German painter Gerhard Richter, in 2002. So it's been nearly a decade since the quartet last recorded together, despite touring on a semi-regular basis, including a sublime performance at the 2010 Ottawa International Jazz Festival, that came a night after he played with Beautiful Dreamers—Kang and drummer Rudy Royston—at the same festival.

Beautiful Dreamers largely focused on material from its then-upcoming, self-titled debut (its first for Savoy Jazz), but 858 wasn't playing any of the music that would come to be recorded four months later, at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, California, for one simple reason: Frisell had yet to write material for the new 858 album. The guitarist wouldn't do so, in fact, until just a month before the studio session, when he spent four weeks at an artists' enclave in Vermont, called the Vermont Studio Center. "I've never done anything like that before," Frisell explains. "I was in Vermont for a month, at this Vermont Studio Center. It's in a little town called Johnson, Vermont, and it's about an hour from Burlington, so it's way up there. It's an amazing, beautiful place: mainly painters and sculptors and writers; they've never had musicians before, and they don't even really have facilities for musicians. I was in a painting studio, this empty white room with a desk, and it was incredible just to have that kind of space and time.

"I can't even remember when I've had that much time—maybe when I was just out of college and didn't have any work, and I'd just sit around and practice—maybe it was a little bit like that," Frisell continues. "But I had blocked off that time—my wife is a painter, and that's how I found out about the place— you apply to go there, and there's about 50 artists there at one time. We both went there at the same time, and we each had a studio. I knew I was going to record at the end of that period of time, and I already had older music that I knew we [858 Quartet] could record. We hadn't recorded in a long time, and there was a lot of material already, so I didn't have that pressure where I felt, 'Oh god, I've got to come up with the stuff.' So I just wrote for the sake of doing it. There really wasn't any pressure—I was just free to write and write and write. So I'd go in every day, and whatever came into my mind, I wrote it down. I accumulated all these pieces of paper; it was just a completely different kind of experience. Then they [858] came at the end of the period—the last couple days I was there—and we just read through some of it, we did a little informal concert for the people up there, and then we went and recorded it."

While Sign of Life feels as though it was composed as a near-continuous suite, with certain themes cropping up more than once throughout its 54-minute, 17-song set, that's not how it came about. "I don't even know how many pieces I actually wrote," says Frisell. "I guess that happens later [putting the music together into sequence]. It's always kinda like a puzzle. When I'm actually writing, it's hard for me to see the bigger picture—it almost gets in my way if I think that way. I have to just let whatever comes out come out, and then accumulate all this stuff. It's more in the editing that some sort of a larger form starts to appear, and then I might take something—like, if there's this one melody, I'll do it in a bunch of different ways. That happened a lot on the Disfarmer (Nonesuch, 2009) album; there's a lot of things coming from this one little melody that runs throughout the whole album."

One of Frisell's most intriguing qualities is his ability—unlike some artists who prefer not to look back and revisit older material—to continue mining the same material in a variety of contexts. He can take a relatively simple melody, like that of "Baba Drame," from the pan-cultural The Intercontinentals (2003) and, through patient repetition and subtle variance, evolve it almost imperceptibly, to new places, nevertheless. "That's what I'm hoping for every time I play," Frisell explains. "I don't want it to be the same; it's just in the nature of the way I play and the folks that I play with."

Still, while it's not a particularly novel notion, especially in jazz, that every performance should be different, it's how Frisell works in the context of a group—and in the context of 858 Quartet, in particular—that distinguishes his music. While individual voices come and go, it's less about delineated soloing and more about a collective improvisational approach that, in the case of Frisell, doesn't just mean interpreting the players' individual parts—it's about making decisions, in real time, about what those parts are and who plays them. Frisell's credits in the liners to Sign of Life say it all: "All arrangements (on the spot and subject to change) by Bill Frisell, Eyvind Kang, Hank Roberts and Jenny Scheinman."

"I don't even really know how it works, exactly," Frisell reveals. "Sometimes I might have four clearly defined individual parts, but I might not say who should play what. We just start playing, and the really quick, instinctual kinds of decisions that these guys are making about who's playing what changes from night to night. Everybody knows what everybody else is playing; everybody has the same information. It's not arranged in a fixed way, so it's more of this spontaneous arranging kind of thing, and it really amazes me. Every time we get back together after some time apart, I'm worried about how I'm going to get this together, how am I gonna figure this out; and then we just start playing, and it's almost like magic the way it happens.

"I write the notes down, so I guess I compose it in a way, but I wanted to make note of that [how 858 arranges the music] in the liner notes: that it's not like I have this stuff all figured out, and they're reading it down—the line between what's composed and arranged, and orchestrated and all that. ... I love that sometimes there's an obviously featured instrument, but mostly, everybody's just playing together at the same time, and it's not really figured out, not worked out so much.

"We're all friends, and there's this understanding and trust," Frisell concludes. "I don't have to explain anything. Everybody that I've been playing with lately, it's not like I've got something to show them— I'm looking for them to show me something. There nothing to figure out; we don't have to talk about it, we just start playing. I don't have a fixed idea in my head—I mean, I'm hearing something in my head, but I thrive on it always mutating. We all have that attitude that every time we play, we're going to try to find something else in there, something that we haven't found before."

With every show recorded by Frisell's road manager, Claudia Engelhart, there's the possibility to listen back after a performance, as some groups do, to try and assess what worked and what didn't. But Frisell steadfastly avoids doing so. "I just never listen to this stuff," he explains emphatically. "When you have a really good night, one of the biggest traps somehow—and I guess that's why I don't like to listen back—is that you can get attached to something. Whether it's good or bad, if you're thinking about something that happened before, then it takes you one step away from being in that moment when things are happening, when it's supposed to be happening. When you have a night where some sort of unbelievable transcendental amazing thing happens, the hardest thing is: if you're thinking about that the next night, you're bound not to get it happening. You just can't be attached to anything, and the only way to have it happening is if you're really right there, right then."

Frisell's approach has evolved over the years, but it's clear when following his music that there's something, some sound, that the guitarist is hearing and trying to reach—from his first release as a leader, 1983's In Line (ECM), through Nonesuch recordings like his "covers" album, 1993's Have a Little Faith (one of the most eclectic sets of covers ever released, placing Aaron Copland and Charles Ives beside Bob Dylan, John Hiatt and Madonna), his watershed 1996 recording, Nashville, and more recent fare like Unspeakable. Sometimes he applies a bevy of effects processing, as he did in his early days with ECM on albums like saxophonist Jan Garbarek's Paths, Prints (1982) or bassist Eberhard Weber's Later That Evening, released the same year; at other times, his sound is completely unaffected—just a guitar plugged into an amplifier, the approach Frisell uses, for the most part, on Sign of Life.

"Even from day to day, it changes," Frisell reveals. "It's so liquid, this thing that's out there. Sometimes it can be this real guitar-ish thing—like I'm hearing the sound of some old Telecaster in my head or I'm hearing Scotty Moore playing with Elvis Presley—but then the next moment, I'm hearing an orchestra in my head or somebody singing or drums.

"That's just been the nature of music," Frisell continues. "I've said it before. I'm 60 years old, but when I pick it [a guitar] up, it doesn't feel very different from the very first time I touched a guitar. You grab hold of this thing, and you think, 'Man, what I am I gonna do.' You're sort of imagining this thing, and you're trying to get it, and you just go for it somehow, but you can never get it. Every day of my life for the last 50 years, I've been trying to get this thing that always stays just a little bit beyond my reach. It's a weird thing with music. I know it's easy to get intimidated or discouraged by that, but you have to get comfortable with the idea that you're never going to get there; that's just part of what it is.

"It's just this gigantic world of music that's floating around—not just in my head, but it's out there," Frisell continues. "When I get going playing, I'm just grabbing at all these things, but from moment to moment, it changes. As I'm answering here, I'm not sure if I've ever really thought about it; it's impossible to describe. There's just always something there that you're reaching for, but it does change—a lot. And it so much has to do with the people I'm with. I played clarinet when I was growing up, and the experience I had playing in bands and orchestras and the few times I played in a woodwind quintet—I remember the feeling when you got a blend with the other people and the feel of those instruments together in a room. The way 858 plays together, it's not that different from when I was in high school playing in a woodwind quintet, in a way. I much prefer that, and am more sensitive to that than the artificiality of having everything in monitors and amplified. I mean, I still do that—that's the way of the world we live in—but it's being generated more from this sensibility. ... Even if it's a rock band playing loud, there's still this thing that, for me, comes from that sound of people playing in a room."

Most of Frisell's groups—and 858 in particular—set up in a very tight semicircle onstage, not just for eye contact but so that they can all hear each other naturally. The groups sometimes play so quietly that a whisper is a roar. Frisell sometimes seems to channel Jim Hall by—as he recalls someone saying about the influential octogenarian guitarist—"'using an amp so he can play quieter.'" Frisell explains, "I want my attention to be fully on them. Sometimes people in the audience get pissed off, saying, 'Why don't you face the audience; I want to see what your fingers are doing,'—all that kinda stuff. But it totally doesn't make sense for me to play music that way. I'm making the music for the people to hear, but to get to it I have to be absolutely focused on the people that I'm with."

An issue that is raised regularly about Frisell—and the softer, more lyrical nature of Sign of Life, as opposed to some of the more angular and jagged music on Richter 858 is sure to bring it up again—is the idea that he's somehow lost his edge. True, his recent music has not been as aggressive as some of his earlier music, like his Nonesuch debut, Before We Were Born (1989), but the idea that Frisell's music is somehow less adventurous is as puzzling to him as the seeming need to define his career in periods. "For me, all those things [his varied musical interests] have been pretty much there as long as I've been recording," Frisell says. "I don't really think of it that way, but if I'm cornered and have to think about it, all the stuff has always been there. I always get uncomfortable being put into slots— that first I was an 'ECM' guy, then I was a 'Downtown' guy, and then I was an 'Americana' guy. While I was making ECM records, I was also playing with Ronald Shannon Jackson. All these things have been happening simultaneously.

"But then I went to Nashville," Frisell continues, "and that was a big step for me, just for me to grow, to learn about this other music. That's another thing. In some reviews, maybe because the music was more tonal, they would criticize it, saying I had sold out. For me, it was actually quite a bit more risky. That [Nashville] was one of the most adventurous things I'd ever done—to go to Nashville and play with all these people that I'd never met, to try and find a language to play together with people I didn't know—it was a way for me to look further into the music than where I had come from before.

Beautiful Dreamers, from left: Eyvind Kang, Bill Frisell, Rudy Royston

"Just because I turn on a distortion box, does that give it an edge?" Frisell puzzles. "It's weird, I don't know; maybe, I guess. It's so personal and private, what a musician is really doing. I'm the only one who really knows what I'm trying to do. I could be doing something that's internally extremely difficult, and it could be something simple. There's something about just playing a major chord—there's a million ways you can do that, there's all kinds of intensity that can happen."

Even an album like the relatively overlooked The Willies (2002)—on the surface, a bluegrass record furthering the work of Nashville, but with bassist Keith Lowe and banjoist/guitarist/harmonicist/keyboardist Danny Barnes, where Frisell demonstrates his ability to take even a simple major chord and turn it on its side with the slightest change to the voicing—possesses its own kinds of risk. "I'm thinking of what I was trying to do," says Frisell. "So much has to do with the people I'm playing with. The Willies thing—I was playing a lot with Danny Barnes. I was taking lessons with him and trying to learn tunes from him—learn some of the language that he has, coming from growing up in Texas, playing the banjo. And I wanted to check that out; it was like a way to enter into these places and learn about them. But for me, there's room. I need all that stuff; the world of music is so huge, and there's room for all that stuff—and it can even all happen at the same time. It's all good."

It's a given that music is often a reflection of who we are; but equally, it can be a reflection of where we are. The softer-toned Sign of Life, written, as it was, in the heart of the northern Green Mountains of Vermont, makes total sense, despite having moments, like on the title track, that are compositionally reminiscent of Where in the World? (1991), and other moments, like on the opening track, that possess the rootsier reflections of albums like Good Dog, Happy Man (1999). Frisell continues his hectic schedule, with more Live Download Series on the horizon and, of course, no shortage of live performances. Recent and upcoming releases include Lagrimas Mexicanas (E1 Music, 2011), a duo recording with Intercontinentals partner Vinicius Cantuaria; Buddy Miller's Majestic Silver Strings (New West, 2011), an equally tremendous record that teams Frisell, in addition to Miller, with Greg Liesz, Marc Ribot and a group of singers including Emmylou Harris, Patty Griffin and Lee Ann Womack, for a singer/songwriter album with a difference; and a sequel to the collage-like Floratone (Blue Note, 2007), which is nearing completion, with planned release also on Savoy.

But another forthcoming Frisell project, perhaps more than most, demonstrates his intrinsic reflection of the where as much as the who. "Yeah, I've thought about it," says Frisell. "I travel so much, and I do notice that from place to place, though it's such a subtle thing. I'm so affected by the air, by the temperature. When I did Disfarmer [an album largely inspired by the Depression-era photographs of Michael Disfarmer], I didn't want to just look at those pictures in a book, I wanted to be there in the town were the guy was.

"For me, it gets more and more important where I am," Frisell continues. "In the spring [2011], I'm gonna be doing this project of Bill Morrison, the filmmaker. He's gonna do a film using this old archival footage of the New Orleans flood from 1927. It's still in the really early stages—I've been thinking about it, but I haven't done much more. But for that, I'm actually gonna go play with Tony Scherr and Kenny Wollesen and Ron Miles, and it's all abstract—I don't even know what the film is gonna look like. But it's old footage from that time—this horrible, Katrina-like event—but it also had a lot to do with people migrating up north; they just couldn't deal with being there anymore. And it parallels the music: going from more rural things to people moving up to Chicago and more city stuff, the music went from acoustic to electric; there was all that kind of stuff going on.

So we're gonna play in New Orleans and St Louis, and travel up and down the river [Mississippi] a bit, to get it together. I've never really done that with a whole band as the music is being formed. I was thinking it would just be so cool to do this with everyone there at the same time so we get this common feeling—to be in Mississippi and to play together. There's no way you could write that on a piece of paper."

Like his Music for the Films of Buster Keaton (1995), Frisell plans to perform the music live as a true soundtrack to the film, which will also be presented. But in the meantime—between two (possibly more) recordings on Savoy Jazz, Lagrimas Mexicanas, Majestic Silver Strings, the second Floratone, the John Lennon Tribute and the Live Download Series, which continues to release a new show every other month—the diversity of his work is clear proof that, while some continue looking for ways to categorize Frisell's music, his multifaceted interests have always been more about expanding horizons, and broader consolidations. There's really no single description that fits Frisell anymore, other than that—no matter what he does or with whom who he does it—his voice is recognizable from the very first note. For any artist, it rarely gets better than that.

Selected Discography

Bill Frisell, Sign of Life: Music for 858 Quartet (Savoy Jazz, 2011)Bill Frisell/Vinicius Cantuaria, Lagrimas Mexicanas (E1 Entertainment, 2011)

Buddy Miller, Buddy Miller's The Majestic Strings (New West, 2011)

Bill Frisell, Live Download Series (Songline/Tonefield, 2011)

Bill Frisell, Beautiful Dreamers (Savoy Jazz, 2010)

Bill Frisell, Disfarmer (Nonesuch, 2009)

Jim Hall/Bill Frisell, Hemispheres (ArtistShare, 2009)

Bill Frisell, History, Mystery (Nonesuch, 2008)

Bill Frisell/Matt Chamberlain/Lee Townsend/Tucker Martine, Floratone (Blue Note, 2007)

Paul Motian, Time and Time Again (ECM, 2007)

Bill Frisell/Ron Carter/Paul Motian, Bill Frisell, Ron Carter, Paul Motian (Nonesuch, 2006)

David Binney, Out of Airplanes (Mythology, 2006)

Bill Frisell, East/West (Nonesuch, 2005)

Bill Frisell/Petra Haden, Petra Haden and Bill Frisell (True North, 2005)

Bill Frisell, Richter 858 (Songlines, 2005)

Bill Frisell, Unspeakable (Nonesuch, 2004)

Bill Frisell, Blues Dream (Nonesuch, 2001)

David Sylvian, Everything And Nothing (Virgin/EMI, 2000)

Bill Frisell, Good Dog, Happy Man (Nonesuch, 1999)

Kenny Wheeler, Angel Song (ECM, 1997)

Bill Frisell, Quartet (Nonesuch, 1996)

Bill Frisell This Land (Nonesuch, 1994)

Don Byron, Tuskegee Experiments (Nonesuch, 1992)

Bill Frisell, Where in the World? (Nonesuch, 1991)

Bill Frisell, Before We Were Born (Elektra/Nonesuch, 1989)

Tags

Bill Frisell

Interview

John Kelman

United States

Kenny [Wollesen]

Hank Roberts

Rudy Royston

Bob Dylan

John Hiatt

Jan Garbarek

Eberhard Weber

Jim Hall

Ronald Shannon Jackson

Ron Miles

John Kelman

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Bill Frisell Concerts

Feb

2

Mon

Mar

29

Sun

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.