Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Geni Skendo: Breaking Free

Geni Skendo: Breaking Free

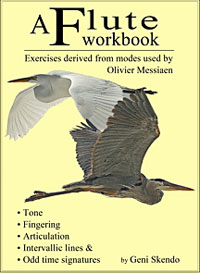

Working at pizza shops to support himself in the city, eventually he landed himself a scholarship at New England Conservatory, where he availed himself maximally of all resources and authorities. Nothing outran his curiosity. Imbibing a brimming course load at the institution, he broadened his cultural horizons and commenced an odyssey of bonding together all manner of beautiful music—from Albanian folk and European classical (in addition to an exercise book for shakuhachi, he has recently published one for flute, derived from modes used by Olivier Messaien), to free jazz and funk.

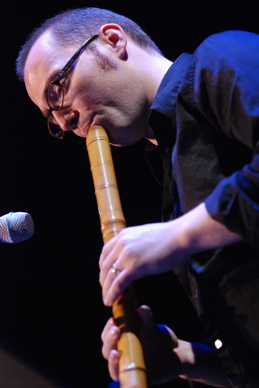

Witness his two releases thus far: the exquisite Portraits: Shakuhachi and Piano Duets with Dominik Wania (GeniMusic, 2008) and the sultry, R&B-flavored Stella (GeniMusic, 2007). Skendo moves at the speed of his own mind, trying out new templates and painting with new sonic palettes, all the while evolving a unique and personal style. The most noticeable thing about his music, at first, his is gorgeous, precise, impeccable tone—one that he can modify for the most divergent of styles. That would be enough, but he can improvise skillfully and, in addition, lead an ensemble with confidence and aplomb. Breaking molds with the force of an iconoclast, with one hand, he reshapes them with a deep taste for tradition with the other.

All About Jazz: It's always fascinating to hear the story of a musician growing up in another country. Can you tell us something about what it was like growing up in Albania, and your exposure to music there, and your family background?

Geni Skendo: I started to play flute when I was six years old—flute and piano. My father was in the army; he was a pilot, a colonel. He wanted somebody in his family to be in music. He was a kind of loner, war-hero personality, doing sports. He saw the orchestra and thought, if I was a violinist there would be about 20 others, but if I played flute there would be only one or two. He put me in music...

AAJ: As a way to discipline you?

GS: I didn't want to do music. I wanted to do sports because my father was in sports the whole day, so I wanted to do sports! But he made me practice music the whole time. So Albania, during Communism was very closed. There was only classical music, and that limited to the ones of the Russian influence...

AAJ: How old were you when the regime fell apart?

AAJ: How old were you when the regime fell apart? GS: I would have been about 14 or 15. And I went to the conservatory for classical music, and after that I began to work in the Albanian National Folk Ensemble, and it was interesting. I learned a lot of cool Albanian tunes. It was also hard because, coming from classical music, you have to let go all the control and precision that you learned in classical music, so it was the total opposite. So when I began to play folk music, I also began to play more jazz. Also, I picked up the saxophone, to make some money on the side. But jazz or improvised music or new music—it was very minimal and the level was kind of mediocre. I didn't want to live my life in mediocrity, musically speaking. I could be 50 years old, and young kids could come and take my job. And I hate monotony. And then I came to Boston to study at Berklee.

AAJ: When did you make the choice that you wanted to do jazz?

GS: That happened gradually, around 2000, when all the change began to happen. Everything in the system was corrupt. You couldn't get a gig unless you were a hot chick, or your brother worked for the minister in the government. But I did a couple of recordings for the Albanian Radio Television Orchestra, a couple of jobs for them. But with jazz, I said, it's so personal, and I can do my own thing.

AAJ: What was your first exposure to jazz?

GS: Now, that's a funny story. I had a friend who was going to conservatory, a violin player, and he was blind. So he had to learn all this classical stuff by ear. So I had to read him parts, and he memorized it. He had the most awesome ear. And so he began to teach me some songs by ear because he wanted to play piano, and I began to learn some stuff. Of course, there was no jazz. And this guy began to teach me some simple stuff, kind of bluesy, like Latin—but little. I mean the guy was ignorant himself, also.

AAJ: Of jazz?

GS: Yeah. He started to learn, on the radio in the village, and he told me. So I said to him, "Hey, man, can you give me the name of some CD so I can go and find it? Because it sounds really cool." I told him I heard some jazz before, but I didn't really like it. So he said, "Go find this pianist called Miles Davis!" Now it's Albania, so it makes sense that I didn't know. My family was not intellectual. My father was in the army, and my mother made telephones, worked in the post office—simple people.

GS: Yeah. He started to learn, on the radio in the village, and he told me. So I said to him, "Hey, man, can you give me the name of some CD so I can go and find it? Because it sounds really cool." I told him I heard some jazz before, but I didn't really like it. So he said, "Go find this pianist called Miles Davis!" Now it's Albania, so it makes sense that I didn't know. My family was not intellectual. My father was in the army, and my mother made telephones, worked in the post office—simple people. So I went to the only store in town where I knew he had jazz. The guy who ran the store—grumpy bastard. The guy loved jazz, a jazz fanatic, but stuck in Albania. He didn't see anybody; he made a living selling Albanian folk music that he hated. And I went there and I told him, "I'm looking to buy some jazz."

And he said, "What kind of jazz?"

And I said, "A friend told me about this pianist called Miles Davis."

The guy said, "Miles Davis is not a pianist!"

I bought Kind of Blue (Columbia, 1959), and I got something by Pat Metheny, the guy was playing then. There was no internet then, or very little, so I couldn't find information. I began to learn some stuff by ear, very minimal, and transcribed them.

AAJ: So, that was a very early, natural gift for you—to be able to play things by ear and transcribe them...

GS: I had perfect pitch, because one thing my father could control about music was my ear training. He would say, "Okay, now let's do some ear training. Find this note on the piano!" He used to do it with me all the time. He would throw a glass on the floor and be like, "What note is this?" So I had to find it. Not that he'd find it, but I had to try. When you do this all the time, you learn. I appreciate my father doing that now. He did it for the wrong reasons, but it's okay. So in Albania I began to play some jazz. Compared to what I do now, the level was nothing. But then, it was a lot.

So, when I came to study at Berklee I was like, "Wow! I know nothing." It was very humbling because I had a lot of experience playing in performance, but the level here is so high.

AAJ: You felt that, but you had a background that others didn't have...

GS: That's true, but where do you apply the experience, if you don't have the other skills that you need, to get to the levels where people can see you. Some people might hire you to play only two lines, a short solo, but are you qualified to play that? You have to have the vocabulary, the experience—the experience that will come out when you play only one phrase...

AAJ: So was there anyone who jumped out and recognized your dilemma and helped you through that?

GS: It was a process. When I went to school, I didn't have time to practice much because I needed money, so I was working in restaurants making pizzas. I was working in a Greek pizzeria, with uneducated people—all these people who came to the U.S. just to make money, but I had been in intellectual circles, performed with the biggest musicians in my country—so I was very pampered, in way.

AAJ: Really? In Albania aren't many people poor?

GS: It is poor, but things work with circles, so you have this job, and this other job, and this other, where you play music. And that's what you do. I was kind of sheltered there. But I thought, if I'm going to study music here, I better get the maximum out of my time. So I had no shame about asking anything music-wise. So what I did—a friend of mine, Matt Marvuglio, the dean of Berklee, he gave me free lessons. He did the same work when he was younger, making breakfast, making eggs, so he understood.

When you play jazz flute, it's hard. You have to learn the language so you can apply it to the instrument, but a lot of young musicians focus on the instrument too much, instead of learning the music. So I was too much focused on learning the effects...

AAJ: So you dropped out of Berklee?

AAJ: So you dropped out of Berklee? GS: Yes. But I had some other friends there, faculty. I just bothered them the whole time, stalked them. "How do you do this? How do you do this?" I mean, it's music, not money, so people share ideas. Afterward, I picked up the shakuhachi.

AAJ: Where did you find the shakuhachi?

GS: I bought it online—a PVC (plastic) shakuhachi—because I heard it on Japanese movies. It's cheap—50 bucks—and first, when I was doing a demo to perform with friends, I recorded a song with shakuhachi. It's called "Sugar," by Stanley Turrentine. It was pentatonic, in C minor. But I played it with shakuhachi in D minor, the scale of shakuhachi. Just for fun. I was trying the color. I picked it up just for fun. But the band loved it! "It's really cool," they said. "Play some more!" And really, when I played, it energized the group more than my flute playing. And when people like what you do it makes it easier for you, psychologically, to do more work, and get more done.

So I would bring my shakuhachi to work when I was making sandwiches. And I would play it on break, and the customers loved it. When I got a little bit better, I applied to New England Conservatory and I got in on a scholarship.

So I would bring my shakuhachi to work when I was making sandwiches. And I would play it on break, and the customers loved it. When I got a little bit better, I applied to New England Conservatory and I got in on a scholarship. AAJ: You seem to have had a lot of misfortunes that turned into opportunities.

GS: Yes. My visa was running out, and I wanted to stay. I had just made a demo with my friend on bass. We played John Coltrane's "Naima" [from Giant Steps (Atlantic, 1959)]. I played the melody and then I said, "I'm going to play what I want!" You know how you feel a lot of frustration sometimes, you have something to say—with that flute I could connect and express energies. So I played and it was kind of like jazz, free—but kind of skeleton-composition performance, and it was good, and they offered me a good scholarship so I was able to afford the school.

When I went, I said, "I'm going to start with as many teachers as possible," because they're all great. What makes them great? How did they get there? What do they do musically...

AAJ: So it's just as much a study of the teachers themselves as what they were teaching you.

GS: Yes, because it's all connected.

AAJ: You're very conceptual.

GS: I have to be, because if you come from Albania, you always have to think about the big picture, or else you get depressed. I studied with Charlie Banacos for two years—the jazz guru. He plays the piano, but he's a composer. You study ear training, composition with him. I did jazz boot camp with him. He had me write solos, transcribe stuff. And it's funny, all the stuff I was doing with standards, it was free. Because I sing different. I studied Indian music, I studied percussion one semester, I studied for one year with Anthony Coleman.

Anthony was amazing. When I did my audition for him, he said, "A lot of what you were doing was really great, and you were going in some directions where I was really digging it; but at some moment, you lost it." So I said, "Can you help me to get there? Because I want to do stuff, but honestly I don't know how." I was not as conceptual as now. So what we did with Anthony was a kind of musical psychoanalysis. He had me improvise, and he told me the truth, and he had me do different stuff and read different stuff. But he questioned everything I did. Writing this, writing that—in the end, I figured out why I liked what I liked. Sure, I'm going to play better later, but it was good.

One of the guys who really inspired me was Joe Morris. I learned more from talking to Joe Morris than anybody else. He's able to analyze stuff and tell you what's the next thing you should do. He makes things very simple. He finds the most simple thing you can do to change something. He really helped me to play free. I was playing free, but getting lost. He taught me that if you free your brain, you can do anything. He took me under his wing and invited me to his shows, I played with him a couple of times. I recorded a CD with him.

AAJ: Let's talk about your projects. What was your first ensemble in the U.S.?

GS: You know, breaking free: you don't break free right away. It's a process. It happens little by little; it happens one moment when you play a good solo somewhere. But it starts slowly. It happened for me. I was playing for some friends' recordings at Berklee. I was not even a student there. This type of thing started to happen more and more often. A pianist asked me to play—Kevin Harris. My teacher, Matt Marvuglio, asked me to sub for him at a gig.

GS: You know, breaking free: you don't break free right away. It's a process. It happens little by little; it happens one moment when you play a good solo somewhere. But it starts slowly. It happened for me. I was playing for some friends' recordings at Berklee. I was not even a student there. This type of thing started to happen more and more often. A pianist asked me to play—Kevin Harris. My teacher, Matt Marvuglio, asked me to sub for him at a gig. It happens. There are different levels—the financial one where they call you for jobs and you get paid. I played a lot of weddings with this guitarist. That's good. But Joe Morris asked me to play for a faculty concert at NEC. Joe Morris on bass—it was bass, shakuhachi and violin.

Another one that helped me was when I played with The Violent Femmes. I know them because I bought the shakuhachi from the bassist. We became friends online, but honestly I didn't really know them at the time. My wife asked me who I bought the shakuhachi from, and I told her it was this guy from this band—I don't even like their music. And she said, "They are cool! They have a cult following. I even made out with a boy during one of their songs." So I played with them in concert. They said, "Okay, play a solo."

So I took this free, jazzy, Ornette Coleman kind of solo, mixed with Jethro Tull. Very rhythmic, but spread around—putting a lot of patterns in, a lot of energy. When people yell at your music, it's a great feeling.

You have to find a way to communicate with people, and that comes with energy. What I like about free jazz is people play their ass off. But to do that, you need skills. It can also come from space or tone color.

AAJ: Tell us more about your other projects.

GS: I have different projects. Two of them are with Brian O'Neill The main one is Orchestrotica, and a smaller one—a quartet. Brian owns a big bass flute. I love it. So it's bass flute, vibraphone, upright bass and percussion. It requires me to have the control of a classical player. Everything is very detailed and precise, but also jazz solos with free moments—the best of both worlds. But it's challenging, especially with the bass flute. And I don't own a good bass flute; I have a Chinese one, so I have to work harder. I also have a duo with Brian: shakuhachi and percussion. Asian, folk, contemporary music. On the one hand, I play Japanese music, and I use different projection techniques, like using triads and different patterns. And also, Brian plays free jazz on—not drums, but ethnic percussion. And Brian is very tasty on that, so it gives us great space and this beautiful color. So with them, we performed at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

GS: I have different projects. Two of them are with Brian O'Neill The main one is Orchestrotica, and a smaller one—a quartet. Brian owns a big bass flute. I love it. So it's bass flute, vibraphone, upright bass and percussion. It requires me to have the control of a classical player. Everything is very detailed and precise, but also jazz solos with free moments—the best of both worlds. But it's challenging, especially with the bass flute. And I don't own a good bass flute; I have a Chinese one, so I have to work harder. I also have a duo with Brian: shakuhachi and percussion. Asian, folk, contemporary music. On the one hand, I play Japanese music, and I use different projection techniques, like using triads and different patterns. And also, Brian plays free jazz on—not drums, but ethnic percussion. And Brian is very tasty on that, so it gives us great space and this beautiful color. So with them, we performed at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Another project I perform in is my band. First it used to be called Shakuhachi Funk Sextet, because I was too much into the funk then—before I learned! And now, it's called Geni Skendo World Jazz Ensemble...

AAJ: Before you learned what?

GS: It doesn't matter what the name is, it's about the music. I wanted to think it was funky, but you know, a jazz player, a heavy cat, can be groovy. It was a student mentality, but I didn't know. And now the music I do with my—sometimes a quintet, sometimes a sextet—it has a drum set, percussion, piano, upright bass, guitar (Ben Levin, the guitarist, plays microtonal music as well), and bass flute and shakuhachi and flute. So with this one, I found people who are really good at what they do. The drummer is Dave Fox. He plays R&B, jazz, funk, free jazz; Noriko Terada on percussion. Ben plays like Frank Zappa in addition to the microtonal work, and he also plays Asian, so he's very flexible. Takeshi Ohbayashi plays piano, and Will Slater is the bassist.

We do my original music, but also other people's. The way we do it is, I process things. We process things. We eat food, and we process it; we hear something and we say what we think about it. I hear their music, and I play it by ear. I hear how I hear it in my head. I learn something, and I sing it this way, or maybe I sing it differently, and the music mixes up in my brain with the stuff that I do. So, in the end, it's a mix of these odd rhythms...

AAJ: So you'll hear it and reprocess it in your head and send it back out...

GS: Oh, yes. I really like tone colors, so that's how I do my band. If I were standing outside to analyze my band, it would be like this: drummer plays odd rhythms, plays funky but goes to free jazz in the middle of the funk tune; goes from jazz to out, back to the rhythm. Funk, out, the rhythm. Percussionist plays ethnic grooves the whole time, even during the free jazz, because I like that! This mix of colors, of worlds. The pianist has this classical touch, but also plays jazz. When I want to play this pattern, if you like, the guitar plays the string pad. These voicings—they start from the melody, they go out; they go in and out the whole time. Of course, we go completely free some of the time, but it's from the song, like another part of the song. It's basically what every good musician does, on different levels.

AAJ: When you're living under a Communist regime, you sort of have to break...

GS: Break free.

AAJ: Find your own ways of being free within an oppressive system.

GS: Totally, totally. That's why I always want to break free from structure. So, now, I am relearning structure again.

Selected Discography

Mr Ho's Orchestrotica, The Unforgettable Sounds of Esquivel (Exotica for Modern Living, 2010)

Elena Zoubareva , Allure (Self produced, 2009)

David Fiuczynski, Kiff Esspress ( FuzeLicious Morsels, 2008)

Newpoli, Newpoli (Beartones, 2008)

Geni Skendo and Dominik Wania, Portraits: Shakuhachi and Piano (GeniMusic, 2008)

Geni Skendo, Stella (GeniMusic, 2007)

Photo credits

Page 1: Mike Spencer

Page 2: Courtesy of Geni Skendo

Page 3: Brian O'Neill

Tags

Geni Skendo

Interview

Gordon Marshall

United States

Miles Davis

pat metheny

Matt Marvuglio

Stanley Turrentine

Anthony Coleman

Joe Morris

Ornette Coleman

Brian O'Neill

Dave Fox

Frank Zappa

David "Fuze" Fiuczynski

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.