Home » Jazz Articles » Multiple Reviews » CTI Masterworks: The Second Batch

CTI Masterworks: The Second Batch

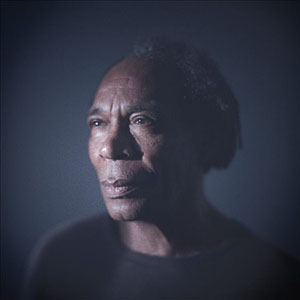

George Benson

George BensonWhite Rabbit

CTI Masterworks

1971 (Reissued 2011)

After three late-1960s A&M albums with mastermind Creed Taylor prior to the creation of CTI Records, guitarist George Benson hit 1971 running with two CTI debuts, issued a few months apart. Beyond the Blue Horizon was closer, in complexion, to his A&M recordings—harkening back, even, to his impressive 1966 Columbia Records two-punch, It's Uptown and The George Benson Cookbook—although the virtuosic, soul-drenched guitarist was clearly evolving as a player and maturing into one whose firebrand, virtuosic tendencies were becoming refreshingly balanced with greater maturity and restraint.

White Rabbit was (and remains) an anomaly in Benson's prodigious catalogue, with its heavy orchestration by CTI regular Don Sebesky. It's also the album that first paired Earl Klugh—a guitarist who, in the face of Charlie Byrd and Laurindo Almeida, took the nylon-string into the realm of light funk and soul—with the electric Benson. The partnership would last a couple more years to the more decidedly groove-centric Body Talk (CTI, 1973), which foreshadowed Benson's rocket to stardom with his move to Warner Bros. and 1976's megahit, Breezin'.

Despite some truly dated material—in particular the title track, an overblown look at Jefferson Airplane's drug-drenched, 1967 hit single—Benson transcends it all, with some brilliant playing, even as "White Rabbit" strives to break out of Sebesky's overbearing bolero-like arrangement. Herbie Hancock, too, turns in an energetic electric piano solo, and comps with soft (and welcome) pushes towards the outer reaches during Hubert Laws' flute feature, creating some much-needed tension and release, even as the track heads towards an overly cluttered ending that, with tympanis pounding, is indicative of CTI at its worst.

That said, Sebesky's gentle strings and harp on "Theme from 'Summer of 42'" are far more successful—and appropriate. It's easy listening, to be sure, with Benson joining Klugh on nylon string guitar, as the song moves into light Latin territory, but the more change-heavy take on a classical piece—Villa Lobos' "Little Train," taken from the composer's "Bachianas Brasilerias #2," is an album highlight; Benson's fleet-fingers matched by Hancock and bolstered by bassist Ron Carter and drummer Billy Cobham, who cook without overbearance.

Another dated track, The Mamas and The Papas' pre-Summer of Love hit, "California Dreamin,'" begins with an almost non-sequitur of Spanish tinges but, more than anywhere else on the album, demonstrates the simpatico interplay between Benson and Klugh, suggesting that Klugh was, indeed, a star in the making. Klugh's gorgeous intro to Benson's closing "El Mar"—the album's only original—sets the stage for an 11-minute highlight that suggests a stylistic breadth to Benson that, despite a subsequent career living as much in the pop world as anywhere else, has continued to this day.

An anomaly in Benson's catalogue, perhaps, and one with its fair share of weaknesses to offset its many strengths, this CTI Masterworks reissue of White Rabbit remains, in many ways, a curiosity that transitions between his more mainstream efforts and the soulful jazz/pop star he was about to become; not without its merits, but not essential either.

Milt Jackson

Milt JacksonSunflower

CTI Masterworks

1972 (Reissued 2011)

With a series of mainstream dates to his credit dating back to the early 1950s—not to mention charter membership in the now-legendary Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ) and one-offs with everyone from bop saxophonist Charlie Parker to "new thing" saxophonist John Coltrane—vibraphonist Milt Jackson was the clear link between his instrument's swing era beginnings with Lionel Hampton and more progressive things to come with then-relative youngsters Gary Burton and Bobby Hutcherson. Still—and despite the label's centrist-leaning proclivities on one hand, balancing out its more groove-centric tendencies on the other—Jackson's signing with CTI Records was something of a surprise, as was his first project, Cherry (1972), an uneven collaboration with label-hit Stanley Turrentine. His first release for the label as a full-out leader, 1972's Sunflower fares much better, even with the presence of Don Sebesky, an arranger who brought out some of the worst of CTI's easy listening tendencies, but, equally, delivered some tremendously inventive and tasteful orchestral work.

Here, with a harpist and 11-piece string ensemble, Sebesky gives Jackson's opening ballad, "For Someone in Love," a burnished sheen, but it can't take away from the vibraphonist's ethereal touch, flugelhornist Freddie Hubbard's more propulsive approach, or pianist Herbie Hancock's abstract impressionism; all making for a stunning intro to an album that posits Jackson in even broader contexts than his discography to date.

The Legrand/Berman ballad, "What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life?," the Grammy-nominated song from Richard Brooks' 1969 film, The Happy Ending, swings with the kind of graceful elegance that Jackson had honed in the MJQ, but Hancock's more exploratory accompaniment drives the tune into unexpected places, even as Ron Carter's low, resonant bass notes support the tune with perfect simplicity.

What was, back in the day, side one of Sunflower was, then, a bit of a shift for Jackson into more accessible territory, but nothing earth-shattering. Tectonic plates didn't move for those who put on side two of the disc, either, but opening with The Stylistics' oft-covered hit, "People Make the World Go Round,"was something new, as the vibraphonist entered light funk territory. Carter, locked-in with drummer Billy Cobham, proves that, at a time when electric bassists like Stanley Clarke and Alphonso Johnson were on the cusp of becoming fusion stars with {Return to Forever}} and Weather Report, the acoustic bass was still the absolute funkiest low-end instrument of all. Hubbard's closing title track is also a foray into light Latin music, with a soft string cushion broadening the soundscape when the tune moves into double-time during Hubbard's plangent solo.

The closing bonus track (not new, it's been on CD issues since 1997), Jackson's "SKJ," feels like something of an anomaly, both in its hard-swinging pulse and production—rawer, and less refined than the rest of the set. It speaks to the truth that musicians may move around stylistically during their long careers, but they don't forget where they came from. A beautiful record that expands an already broad view of Jackson, this CTI Masterworks reissue brings one of the vibraphonist's best albums back into print.

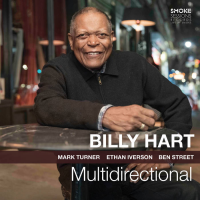

Ron Carter

Ron CarterAll Blues

CTI Masterworks

1973 (Reissued 2011)

In the 1960s and 1970s, few bassists were as ubiquitous as Ron Carter, from the experimental post/free bop of trumpeter Miles Davis's 1960s quintet to straight-ahead swing with guitarist Kenny Burrell and the greater extremes of saxophonist Archie Shepp. With the emergence of CTI Records, Carter became something of a house bassist for the label; on the recent four-CD retrospective box that launched CTI Masterworks, 2010's CTI Records—The Cool Revolution, the bassist appears on no less than 29 of its 39 tracks.

Given his wide-ranging musical interests, Carter's discography as a solo artist remains more than a little curious—largely right down the middle, though he does place himself in a more prominent position as a soloist and melodist. The introduction of his piccolo bass—a smaller upright that, tuned a fourth higher than its lower cousin and, thus, sitting somewhere between double-bass and cello—giving him an instrument capable of taking the lead and remaining undeniably a bass, while occupying a range more appealing to ears of a larger listening public that often had trouble hearing the lyricism of the original low-end instrument. Carter introduced the piccolo bass on Blues Farm, his 1973 CTI debut, but that more pasteurized date was far less successful than its follow-up, All Blues, just a few months later.

Rather than working with the larger cast of characters he did on

Still, mainstream needn't imply that this mix of four Carter originals, Miles Davis' iconic title track, and one standard, "Will You Still Be Mine?," is anything resembling safe, as Carter delivers the Matt Dennis/Tom Adair/Paul Weirick chestnut as an overdubbed bass/piccolo bass feature, closing the album on an unexpected note.

While pianists like Herbie Hancock brought a combination of impressionistic flair and propulsive funk to his CTI dates, and Bob James began his trip down a road to the smooth jazz of later years with Fourplay, Roland Hanna brought a firmer sense of tradition to the relatively few CTI sessions on which he participated. Swinging hard on Carter's opening "A Feeling" with characteristic economy, his a capella intro to the bassist's balladic "Light Blue" is the epitome of simple truth; his touch and subtle dynamics more definitive than embellishment and bravado could ever be.

The bulk of the album features saxophonist Joe Henderson, his improvisational élan balancing Hanna's sparsity. Unlike later versions of "All Blues" that would often run at a faster clip, Carter's version here takes it considerably slower than the Kind of Blue (Columbia, 1959) original, and everyone contributes to its relaxed vibe, especially Henderson's behind-the-beat phrasing and Hanna's measure voicings.

Another winner in the CTI Masterworks series of remastered reissues, All Blues proves there's plenty of room for exploration, even in the middle of the mainstream.

Paul Desmond

Paul DesmondPure Desmond

CTI Masterworks

1974 (Reissued 2011)

With a dry tone, and unhurried phrasing definitive of the emergent West Coast Cool—a relaxed alternative to the edgier hard bop coming from New York—alto saxophonist Paul Desmond had already made a name for himself with pianist Dave Brubeck's quartet on the legendary Time Out (Columbia, 1959). Desmond also wrote the tune that became Brubeck's signature, "Take Five," and, while he passed away too young at the age of 52 from lung cancer, he's left behind a relatively small but significant legacy of recordings that have sometimes become overlooked with the passing of time.

Pure Desmond was only one of two albums the saxophonist made for CTI (though he did record two albums with Creed Taylor for A&M, before the producer started his own label), but it's the absolute winner of the two. A small group album featuring the same three bonus tracks as a previous CD version, with CTI Masterworks' warm remastering and beautiful mini-vinyl-like soft digipaks, it represents a welcome return to print of an album that, despite alcoholism and heavy smoking, finds Desmond in great form just three years before his death in 1977.

With label staple Ron Carter swinging comfortably with Modern Jazz Quartet and longtime Desmond musical cohort, drummer Connie Kay, Pure Desmond stands as one of the altoist's best records—as cool as a calming breeze on a summer's day and as dry as a good martini. The album—a blend of standards ranging from Duke Ellington to Antonio Carlos Jobim—also features the tremendously overlooked Ed Bickert, a Toronto, Canada native whose uncharacteristically warm-toned Fender Telecaster had already been heard in the company of fellow Canadians like flautist Moe Kaufman, and bandleaders Phil Nimmons and Rob McConnell, but whose star mysteriously never rose as it deserved, amongst peers like Joe Pass, Herb Ellis and, in particular, Jim Hall.

The tempo never gets past medium, but there's a simmering energy on some of he material, in particular the Jerome Kern chestnut, "Till the Clouds Roll By," heard here in two versions: the original album version, where Bickert's solo is the height of linear invention and occasionally bluesy bend; and a slightly longer alternate take where he builds a solo filled with rich voicings and single note phrases constantly accompanied with periodic chordal injections. The mix and overall tone of the alternate take is a little rawer, with Carter's bass a more visceral punch in the lower register.

Light Latin rhythms also define the session, with the by-then-popular "Theme from M*A*S*H" given a light bossa treatment, as is Jobim's "Wave," which closes the original album on a graceful note, but here acts as a gateway to alternate takes including the ambling opener, "Squeeze Me," and the Django Reinhardt classic, "Nuages," that skips the guitar/sax duo intro and heads straight into an ensemble reading.

With a supportive group that clearly gets the value of less over more, the aptly titled Pure Desmond stands, alongside The Paul Desmond Quartet Live (A&M/Horizon, 1975)—his other album with Bickert—as the pinnacle of this West Coast cool progenitor's career.

Jim Hall

Jim HallConcierto

CTI Masterworks

1975 (Reissued 2011)

Amongst the many CTI classics of the 1970s, few stand the test of time as well as guitarist Jim Hall's Concierto, an ambitious album that, in its original form, married one side of modern mainstream with a second taken up by a 19-minute version of Joaquin Rodrigo's 1939 piece for classical guitar and orchestra, "Concierto de Aranjuez." That Miles Davis and Gil Evans had already delivered what was considered the definitive jazz adaptation on the trumpeter's 1960 classic, Sketches of Spain (Columbia), and that pianist Chick Corea had grabbed parts as the intro to his now-classic "Spain," were clearly no deterrents to Hall, or to arranger Don Sebesky, who—sticking with this minimalist quintet/sextet rather than the overblown orchestras he'd sometimes resort to on other CTI titles—delivers one of the best charts of his career.

Sebesky perfectly balances the innate economy and astute improvisation acumen of Hall's group with written scores that maximize the beauty of space and nuanced understatement. Trumpeter Chet Baker is in terrific form here, in the midst of a relatively brief cleanup period from heroin and with two strong CTI recordings from the previous year—his own She Was Too Good to Me (reissued in 2010 by CTI Masterworks) and Carnegie Hall Concert, with baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan and a crack band that includes drummer Harvey Mason, and a young John Scofield on guitar. Paul Desmond is also in great shape, interacting particularly empathically with Baker on the swinging opener, "You Be So Nice To Come Home To," before the trumpeter takes over with a solo of surprising fire and even occasional grit.

As is the case on the lion's share of CTI recordings, bassist Ron Carter stokes the engine room—this time with drummer Steve Gadd—demonstrating his remarkable versatility. Appearing on all six of 2011's first batch of CTI Masterworks reissues, and playing, as he does, with three different drummers in a variety of contexts, Carter demonstrates just how malleable he is, and how ideal a rhythm section partner he's always been, all while remaining instantly recognizable.

Hall's career has been founded on a thoughtful and restrained economy that's made every note, every voicing, count. What's most remarkable about his playing here is how perfect his choices still are, nearly 40 years later. It's often easy to look back and reassess performances for what they might have been, but there's absolutely nothing here that could (or should) be changed; pianist Roland Hanna also plays with a combination of melodic invention and Spartan lyricism on the two versions of "You'd Be So Nice," including a bonus alternate that, taken at an ever-so-slightly-slower tempo, breathes a tad more than the album version; though, with slightly softer edges, it's easy to see why Hall and producer Creed Taylor made the choice they did.

With its reading of "Concierto de Aranjuez" standing easily beside the Davis/Evans version on Sketches of Spain, Concierto deserves to be considered an equal classic, and a masterpiece in its own right—proof that music can be deep, modern, timeless and accessible.

Tracks and Personnel

White Rabbit

Tracks: White Rabbit; Theme from "Summer of '42"; Little Train; California Dreaming; El Mar.

Personnel: George Benson: electric guitar; John Frosk: trumpet, flugelhorn; Alan Rubin: trumpet, flugelhorn; Wayne Andre: trombone, baritone horn; Jim Buffington: French horn; Phil Bodner: flute, alto flute, oboe, baritone horn; Hubert Laws; flute, alto flute, piccolo; George Marge: flute, alto flute, clarinet, oboe, English horn; Romeo Penque: clarinet, bass clarinet, alto flute, oboe, English horn; Jane Taylor: bassoon; Herbie Hancock: electric piano; Earl Klugh: guitar (1-4); Jay Berliner: guitar; Ron Carter: bass; Billy Cobham: drums; Airto Moreira: percussion, vocal (1, 4); Phil Kraus: vibraphone, percussion; Gloria Agostini: harp; Don Sebesky: arranger.

Sunflower

Tracks: For Someone in Love; What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life?; People Make the World Go Round; Sunflower; SKJ (Bonus Track).

Personnel: Milt Jackson: vibraphone; Freddie Hubbard: flugelhorn; George Marge: clarinet,bass clarinet,alto flute, English horn; Phil Bodner: flute, alto flute, piccolo, English horn; Romeo Penque: alto flute, oboe, English horn; Herbie Hancock: piano, electric piano (5); Jay Berliner: guitar; Ron Carter: bass; Billy Cobham: drums; Ralph MacDonald: percussion; Max Ellen: violin; Paul Gershman: violin; Emanuel Green: violin; Charles Libove: violin; Joe Malin: violin; David Nadien: violin; Gene Orloff: violin; Elliot Rosoff: violin; Charles McCracken: cello;, George Ricci: cello; Alan Shulman: cello; Margaret Ross: harp; Don Sebesky: arranger, conductor.

All Blues

Tracks: A Feeling; Light Blue; 117 Special; Rufus; All Blues; Will You Still Be Mine.

Personnel: Ron Carter: bass, piccolo bass; Joe Henderson: tenor saxophone (1, 3-5); Roland Hanna: piano (1-5); Billy Cobham: drums and percussion (1-5); Richard Tee: electric piano (3).

Pure Desmond

Tracks: Squeeze Me; I'm Old Fashioned; Nuages; Why Shouldn't I?; Everything I Love; Warm Valley; Tell the Clouds Roll By; Mean to Me; Theme from M*A*S*H; Wave; Nuages (Alt. Tk.); Just Squeeze Me (Alt. Tk.); Till the Clouds Roll By (Alt. Tk.).

Personnel: Paul Desmond: alto saxophone; Ed Bickert: electric guitar; Ron Carter: bass; Connie Kay: drums; Don Sebesky: musical supervision.

Concierto

Tracks: You'd Be So Nice to Come Home To; Two's Blues; The Answer is Yes; Concierto de Aranjuez; Rock Skippin' at The Blue Note (Bonus Track); Unfinished Business (Bonus Track); You'd Be So Nice to Come Home To (Alt. Tk.); The Answer is Yes (Alt. Tk.); Rock Skippin; at The Blue Note (Alt. Tk.).

Personnel: Jim Hall: guitar; Chet Baker: trumpet (1-4, 7, 8); Roland Hanna: electric piano (2, 3. 8), piano (1, 4, 5, 7, 9); Ron Carter: bass; Steve Gadd: drums (1-5, 7-9); Don Sebesky: arranger; Paul Desmond: alto saxophone (1, 4, 6, 7).

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.