Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Anil Prasad: Inner Views, Borderless Perspectives

Anil Prasad: Inner Views, Borderless Perspectives

Put the burden of the interpretation on the interview subject's shoulders. Go into their back catalog and cross-reference nuggets from their past against their current project to do a compare and contrast.

In 1994, Prasad was dissatisfied with the lack-of-depth and diversity found in the conventional music journalism landscape and struck out on his own to create Innerviews website, one of the first online music publications. While some legacy music journalists initially dismissed the non-profit one-man operation as a "fad," labels and artists began clamoring for exposure almost as fast as the number of site hits grew, and detractors were abruptly silenced. In 2010, with over 300 interviews to date, tens of thousands of devoted readers, and naysayers left in the dust, Prasad has released his first book Innerviews: Music Without Borders [Abstract Logix]. The collection features 24 exclusive interviews with iconoclastic musicians including Björk, Chuck D, McCoy Tyner, John McLaughlin, Victor Wooten, and Joe Zawinul. Wooten wrote the book's foreword.

The book has received nearly universal acclaim from dozens of publications including The Los Angeles Times, Christian Science Monitor, and National Public Radio (NPR).

All About Jazz: I remember talking to you about the Innerviews book as far back as 2008. Can you walk readers through the inception of the idea to its release?

Anil Prasad: The inception of the book the resulted from Innerviews readers, saying, "You know, this content you're doing for the web really would be good in an extended book length format." Over the years, several dozen of those emails came through the site's feedback form. I would email these people back and say, "Given that you can get everything on the website for free, why do you want to hold this in your hand? Why does this interest you?" They said there's still something important, impressive and tactile about holding a book and being able to take it anywhere. I carried that idea around for a while. I finally decided to do it thinking it would be a pretty cool snapshot of a moment in time, especially given that the site has been going for so long. It would give me a chance to revisit pieces that I really liked and it would open up opportunities for brand new interviews as well. It was a long and arduous task trying to get a publisher for the book and I talked to all kinds of people. I talked to agents and the B.S. factor was so high in getting a book out that I decided I didn't want to deal with it.

As Innerviews, I'm a one man operation. I can do what I want, how I want, when I want. I asked myself "Why do I want to deal with this collection of idiots, all telling me what it should be?" It was only when Abstract Logix declared its interest that I chose to seriously make it happen. Souvik Dutta, the founder and head of the company, said "Do whatever you want, just make sure it's good." I thought that's a brief I can work with. He literally let me conceive the book as I saw fit, funded it, and played a critical role in making it happen. So that's how it came about.

AAJ: You've interviewed Tori Amos in the past and I noticed she wasn't in the book. Scouring through the Innerviews website, it seems the interviews in the book clearly weren't all based on star power. Can you talk about how you chose what interviews would be in the book?

AP: The decision about what interviews to include was based on the quality of the interview and the Tori Amos interviews were very project specific. One was about a Christmas album and one was about her debut album. They didn't really get deep enough into the broader themes that you find in the book which are about the creative process, collaborations, motivations, history, and spirituality. All of the interviews in the book are very expansive. Also, I didn't just want it to just be about really famous people. That was one of the benefits about Abstract Logix. Souvik said, "As long as there are some things we can hook a marketing effort to, great, but it doesn't have to all be about celebrity musicians." So you have people like Jonas Hellborg, Noa, Martin Carthy, and Michael Hedges. These are incredibly influential people, but not necessarily household names. I actually remember a reviewer who wrote me going, "Who the hell is Jonas Hellborg?" [laughter]. I said, "Well, if you read the chapter you might find out. In fact, that's a good way to learn about who he is." But most of the reviewers have been very, very kind to the book and respect the fact that it's pretty eclectic.

AAJ: How did you come up with the idea of promoting the book the same way an artist would promote a new album, as opposed to the conventional book release approach?

AP: It goes back to a book called White Bicycles (Serpent's Tail, 2007), by Joe Boyd. This is, by the way, a fantastic and essential book chronicling Boyd's work as a highly influential producer for the likes of Pink Floyd, Fairport Convention, Richard Thompson, and Sandy Denny, just to name a few. I spoke to Boyd about the unique way he marketed the book. He said "Why would I put out a book about making music, the creative process and my experience as a producer and send it out to a general book review base as opposed to sending it specifically to music journalists enthusiastic about the subject matter?" This approach worked out extraordinarily well for Boyd. He hired a publicity firm that specialized in music.

And so, I was inspired to take a similar tact with the Innerviews book. The book contains very musicianly-oriented pieces. This may sound like a strange thing to say, but the book is actually about making music. It's not about fashion. It's not about artist cooking tips. It's not about all the silly crap that celebrity journalism has become. Therefore, it made sense that the book should go to music journalists for review. After all, they're the ones who would have previously heard about the artists, and they're people who would hopefully appreciate the in-depth nature of the content, and see some relationship between what they're doing and what's in the book—as opposed to sending it to someone who writes about dance, cinema or cooking, and having that "who the hell are these people?" factor creep in. It was also a question of economics. With a book like this you don't want to send out 1,000 review copies and have 975 of them be ignored. So we took a very highly-targeted approach and made sure to get it into the hands of people who appreciate eclectic music.

AAJ: How did it work out for you?

AAJ: How did it work out for you? AP: It's worked out extraordinarily well. I would say about 98 percent of the reviews have been extremely positive. I'm really happy. I think Boyd's strategy worked. And if there is any music journalist that is reading this who is putting out a book, I would strongly recommend foregoing the traditional book marketing situation unless you're writing a book about Mick Jagger, Paul McCartney or someone who has an existence in ultra-mainstream culture. Instead, go to the people who listen to the music and know and write about music. The other point of the music marketing component is the extremely influential nature of the blogosphere and social media outreach. I think a lot of the reasons this book has achieved any traction is because it's talked about among fans and listeners—people who want to promote the work of the artists contained in the book.

AAJ: Will there be a digital edition of the book?

AP: There are plans for a digital version of the book in 2011.

AAJ: What was it like having other music journalists review you work?

AP: Generally very positive. I guess because the Innerviews website has been around since the dawn of the web in 1994, a lot of music journalists already knew what it was and could make the linkage between the book, the website, and who I am. So I think they've generally been really fair and accommodating. Of course there have been some really silly reviews saying things like, "The cover is very grey. Why is it so grey? Wouldn't some color have been nice?" or "Wow, these interviews are really, really long. Who would want to read such a long interview?" One review went "I've never heard of any of these artists and you probably never have too." [laughter]. Crap like that is pure journalistic laziness, really. I want to emphasize that we're talking about a fractional element here, because the response has been terrific overall. But it is interesting to see what people focus on.

AAJ: On that note, I checked archive.org to see if I could see an earlier version of the site, but nothing was available. Is that intentional?

AP: Yeah, I've done that on purpose. You can't access old versions of Innerviews on archive.org. The interviews on the site, as well as its look and feel, and structure, have become incrementally better over time. The interviews been re-edited and reformatted over time with new graphics added. And while I think there is great value in archive.org, in the case of Innerviews, the best version of the site that you are ever going to see is the one that is up at this moment. No one likes to go back and look at their high school yearbook photos, you know?

AAJ: Stepping back to your formative years as a journalist, you've said that in journalism school you were heavily influenced by your professors' out-of-the-box thinking and alternate methods for interviewing. Can you talk about those methods?

AP: Sure. It's absolutely not rocket science and I don't think you need to go to journalism school to get any of this stuff, although it's certainly helpful if you have the opportunity. Don't ask closed-ended questions. Ask open-ended questions that aren't "yes or no" focused or necessarily revolve around boxed-in answers. You'll see things in the book and the website like, "What's your take on this?" or "Can you elaborate on that?" or "Tell me more about this." They're very simple devices that put the burden of the interpretation on the interview subject's shoulders. I think that's really important. That's where you're going to get the most interesting answers as opposed to something that would result in a yes or no answer.

Another thing of value is really deep research, going into an artist's catalog or looking at previous interviews or articles and pulling out nuggets from their past and cross-referencing against their current project and doing a compare and contrast. If I'm talking to several artists in succession and an interesting topic emerges, I might ask all of them about it. When I interviewed Joe Zawinul, which is still one of my favorite interviews, he said that America is in a state of decline because the number of real storytellers is dwindling. I hit a few other artists with his quote to get their reaction. So many people just took that one and ran with it in interesting and unique ways.

With music journalists, when they receive a CD or downloadable album, it comes attached with a one-to-three page artist biography. For many music journalists, their research begins and ends with that bio. That's why so many interviews read exactly the same. There's a certain amount of carbon copying in music journalism, and there's really no reason it has to be that way. With the web, there's such a wealth of music journalism history to tap into now. In mere seconds, you can Google your way into dozens of articles on the person you're covering and come up with really interesting and novel questions.

AAJ: Why do you think for most journalists the research begins and ends with the enclosed bio, and what makes you different?

AP: I can't speak for every writer, but for some music journalists—those who are really lucky—music journalism is still a job, a paid gig. This is an astounding concept to consider in 2010. Those opportunities are few and far between these days. Sometimes their motivation is their professional survival. Often, they have to write about someone whether they give a damn or not. Then there's the brand of music journalism that is oriented towards three-to-six paragraph interviews—that capsule interview format you see in print so often. When someone is working in the half-page or one-page universe, they have to distill down to the very basics, and basics are usually what are contained within these bios. So they pluck out all the info for the article and away they go. And if you have to generate five or ten of these a month you're dealing severe deadline issues, also necessitating the reliance on the bio.

The thing with the Innerviews website is that I don't get paid to do it. I do it on my own. I lose literally thousands of dollars a year running it. I have a day job that I do to support it. I do it for the love of music. One thing that's interesting is that music journalists get pitched by music publicists day in and day out. Every single day in my inbox there are probably 50 to 100 press releases from music publicists and record labels. Probably five to 20 of them are targeted pitches to me personally. They often get frustrated and they can't understand why they get so little traction with me. It's because I only write about musicians that I'm passionate about. It doesn't have to be a legacy artist with 50 albums in their back catalog. It could be a relatively newer artist. But if I'm writing about an artist, it means I'm really motivated. I want to learn everything I can about their music.

I've got an interview with Bunky Green coming up. He's a legendary jazz saxophonist who I wasn't really aware of until very recently when Rudresh Mahanthappa pursued a collaboration with him called Apex. So I'm talking to Bunky in the near term and his albums are virtually impossible to find. There are about three or four that have been put up for download on iTunes, but otherwise you have to scour the earth to find his back catalog of albums with people like Sonny Stitt. And if I'm going to talk to this guy, who is a celebrated jazz educator and has a mind-boggling depth of jazz knowledge, I better dig deep, find this music and internalize it, or I'm going to look like a hack. [laughter]. Also, I want to come up with something substantive and interesting and of value to people, and I think you can only do that if you really do your research.

Hopefully, the pieces on Innerviews have a long shelf life via the web. Prior to the advent of the web, basically music journalism was disposable. When the issue came down from the newsstands, that was basically it. Goodbye. If you happened to miss that issue, maybe you could find it as a back issue, but with the web, things have the potential to exist forever. I have interviews that stretch back to 1989. Hopefully until the day I'm gone, and even beyond the day I'm gone, these pieces will still be available.

AAJ: What is it that drives you to get inside the heads of the artist, going so far as to buy whole back catalogs and read everything ever written about them?

AP: That's a good question no one has asked before. It's just a complete deep, mad passion and love of the art form that is music. I think it has a lot to do with my maniacal record collecting instincts as well. When I was a kid, back in the day as it were, even in the early days of CDs, I was always one of those people who would sit there with liner notes and pour over them and wonder "What does a recording engineer do anyway?" or "What does mastering mean?" On the early progressive rock albums by Yes, Eddie Offord would show up all the time in the credits and I would think, "Who is Eddie Offord and why is he on all these records? He's not a member of the band." This is when I was eight or nine years old. So in the pre-Internet days I would start buying books about music trying to find out who these people are. I had a lot of musician friends when I was a kid too. I played electric bass for a long time, as well.

I think the combination of those interests with journalism school really spurred me to pursue music journalism. I've got a background doing a lot of journalism outside of music. I've covered speeches by major politicians. I've covered local crime. I've written about movies, dance and theater. I've done television work as well. It's all contributed to this kind of questioning framework I employ in the work. I think all of these experiences swirl together to inform what I do. There's a certain thrill in doing interviews that's never actually left me after almost a quarter century of doing them. It's always a great moment when I can sense the light bulb going on inside the artist's head when they realize, "OK. This guy really wants to go deep and I'm going to let him in." And that's when things really start happening.

AAJ: Have you ever considered doing interviews outside of music, and if so, who would you really like to interview if you had the chance?

AP: Clearly I've solidified on music and musicians as a core focus while keeping a day job and a family intact. It's a pretty comfortable niche and one I enjoy a lot, especially as a record collector and concertgoer. I still go to a lot of live music. A big part of my core circle of friends is musicians or people related to the world of music. All that stuff is always conspiring to keep my interest focused on this realm. But yeah, I've thought occasionally about expanding. Some people have even said, "Now that you've got this book out on music and musicians, maybe your next book shouldn't be about music." I'm interested in a lot of other things beyond music. It would be very interesting to talk to film people like Steven Soderbergh, Errol Morris, Louis Theroux or John Cleese—all people whose work I admire. Interviewing someone like Vaclav Havel or Desmond Tutu could only be fascinating as well.

AAJ: What are some surprises that you've come across while interviewing over the years that you have learned from?

AP: In terms of lessons, you can prepare all the questions you want, but prepare to go completely off script. Be prepared to toss your questions altogether. Some people think that the questions they have written down must be answered, and if they're not getting them answered that something is going wrong. The story you think you want isn't always the interesting one. Sometimes you'll get an artist that doesn't want to talk at all about their current project. They won't answer any of the questions you've put together. I've dealt with a lot of really hard-ass interview subjects. Sometimes you have to figure out what it is that they want to talk about. Ron Carter wanted to talk about not being able to take his bass on the road with him because of the post 9/11 climate. So we did. It was actually really interesting what he had to say about that stuff. Some of these artists just want to talk about something on their mind.

I think what you're trying to do is capture a snapshot of who that person is and where their head is at any given moment. I used to try reining the artists in early on. I remember I interviewed the famous bassist Tony Levin. He had just put out his first solo album. Of course, the only questions anyone wanted to talk to Levin about was about his work with King Crimson and Peter Gabriel. I noticed he wasn't crazy about answering those questions. He actually told me that his goal as an interviewee was to move the interviewer away from those questions and into what he was currently doing as a solo artist. I thought that that was an interesting revelation: the interviewee telling the person doing the interview what they're trying to accomplish. It was kind of an interesting moment for me.

I think after doing more than 300 interviews at this point that I've realized that there's a lot of value in letting the artist drive the conversation sometimes. One of the consistent positive pieces of feedback I get from artists is, "Thanks for allowing me to ramble." I've probably had 40 or 50 people say that to me. The other thing a lot of artists say is, "Wow. That just felt like a conversation. It didn't feel like an interview at all." I think that's another key—to keep things conversational and not seem like you're journo-robot reading questions off of a page. It's better to take a completely human approach that's not that much different from talking to a colleague or an acquaintance, with a little bit of structure. A good interview is basically a structured conversation.

AAJ: A lot of serious music fans can cite a specific moment in time where music hits them. There's a seminal moment where there's some synaptic connection where music takes on the meaning it will have for them going forward. What was that moment for you, and also, how did you get into jazz?

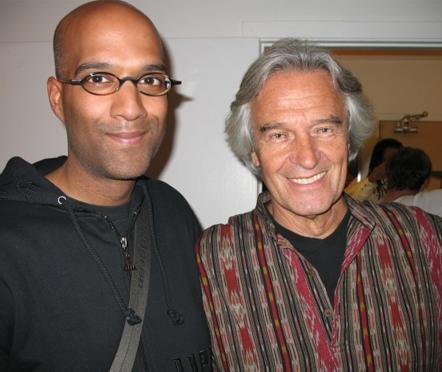

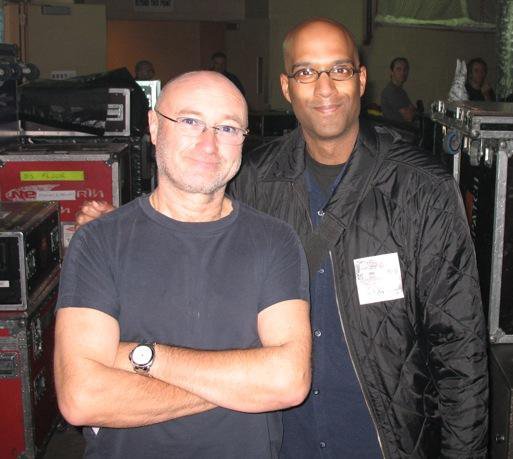

with John McLaughlin |  with Stanley Clarke |

with Phil Collins |  with Chuck D |

AP: It was the group Genesis, and I'll tell you why. When people think of Genesis they only think of the gigantic Phil Collins hit machine. But everything started with an album called Abacab from 1981 by the group. That would have made me 12 years old. I thought, first of all, this is a really interesting album. My friends were listening to Ozzy Osbourne, Def Leppard, Van Halen and stuff of that ilk at the time. I was really out of phase. I kept going with Genesis and started checking out their back catalog. There's a lot of remarkable drumming and epic musical suites on their more ambitious records. Yeah, there's a bit of pop treacle, but at their best, they were an epic prog-rock band. I started digging into the music and going back into the early days of the group with Peter Gabriel, which contained some amazingly ambitious side-long pieces of music. That opened up the whole world of progressive rock. And once you're in the world of progressive rock, if you dig any deeper you will hear elements of jazz, classical, and fusion.

Those were the days where you could still go into a record store and talk to extraordinarily knowledgeable people about music. They would say, "Yeah. You know this Phil Collins guy has done a lot more than what you might be aware of aside from those Genesis records. You need to hear him on this Brian Eno album called Another Green World (Virgin, 1975). And more importantly you need to hear Collins play with a group called Brand X." I was like, "What on earth is Brand X?" They go, "They're what's called 'jazz fusion.' I think you might be interested in this group." For me, Brand X was like progressive rock without vocals with all these odd time signature turns and flashy virtuoso passages. It was really interesting music for a kid.

I would go back to the record store to get some more Brand X music and they would say, "You know, there's this other guy who plays with Genesis you might be interested in. He's a drummer named Chester Thompson. He was a drummer in a group called Weather Report." So, I'm this 14-year-old kid going, "What's Weather Report?" So he hands me the Heavy Weather (Columbia, 1977) album and says, "Go take this home and listen to it." I put Heavy Weather on the turntable and I went, "Holy crap. What is this?" [laughter]. "Is that a bassist? How can anyone make a sound like that with a bass? Who is that?" Suddenly, I'm into the world of Jaco Pastorius, Wayne Shorter and Joe Zawinul. It's interesting, but Genesis got me into jazz and jazz fusion. Once you set foot into the world of Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter, the whole universe of jazz opens up to you if you want to follow it. It's all there. Everything is linked to those two guys through some degree of separation.

Interestingly, in 2007, I got to spend some time with Collins when he was touring with Genesis for the last time. All we did was talk about Zawinul, who had passed away a few weeks earlier. Collins is a huge fan of Weather Report and Zawinul. We talked about the Genesis track "Wot Gorilla?," that was directly influenced by Weather Report. We also discussed how he was friends with Zawinul. In fact, Zawinul asked Collins to play with him on a project, but Collins didn't think he was up to the task somehow. Zawinul apparently told him to "Get in touch when you're ready." Unfortunately, Zawinul passed away before they had a chance to make a collaboration a reality. Meeting Collins and talking about Zawinul was an amazing moment for me given where my journey began.

AAJ: Can you talk about what it's like releasing a book? What surprises have popped up compared to what you thought it would be going in?

AP: It's a complete battle. They don't call it launching a media campaign for nothing. It's almost like going to war. It's an interesting role reversal. It's really hard to get my attention sometimes because the crush of recordings and demands that come my way. So I was on the other side of that trying to get the attention of all of these journalists, all of whom are incredibly busy. We talked about the Joe Boyd White Bicycles thing. A lot of the journalists we sent books to for review weren't used to getting books. So trying to get through their filters and following up was incredibly challenging.

And the cost of mounting a campaign is phenomenal, too. It costs literally $3,000 to $5,000 to hire a publicist to work a book or CD. That's $3,000 to $5,000 that gets added to the cost of the project, and is money that has to be recouped before you ever see a penny. And in many cases the cost of that publicity, combined with the other costs of creating the product, will exceed what you could ever make from releasing the media product itself. It's pretty brutal, actually. So that's a huge revelation. I was very lucky with this book. It got coverage in places like NPR, Christian Science Monitor and the Los Angeles Times, which is remarkable. But the things that you have to do to get there are equally remarkable financially and in terms of time commitment. These days, even if you have a publisher, like I was lucky enough to have, and have a good media agency, again which I was lucky to have, the amount of work on your shoulders is, as the creator of the product, is just astounding.

I've spent dozens and dozens of hours of my life getting the word out there. And I've heard many musicians complain about this too, probably none as loudly as Bill Bruford, who warned me sternly about what to expect. He said with his typical dry wit, "Oh, so, you're thinking about putting out a book, are you? Well just you wait and see how much work that will be for you and let's see what state you're in at the end of that process." And he's right—it's a monumental, all-consuming set of duties that can eclipse the amount of work you put into creating the cultural product that you're promoting.

AAJ: We've talked at length about this in the past and I've also interviewed some more niche artists recently with regard to their stance on label releases and their philosophy. It's been completely varied with some bemoaning the decline of the old label-based establishment and others say they are intrigued about the future. Can you talk about where you see the future of music releases going forward?

AP: I find it interesting when musicians say "I'm waiting to see how this thing shakes out, because we don't know where the future of the music industry is going." Frankly, the future is now. The model has been established. It's here, so deal with it [laughter]. It's a hybrid model; we have the iTunes/Amazon MP3 world, we have the other download sources and aggregators, we have streaming, and there's still the hard copy universe of the CD and LP, including the world of the "super-deluxe" physical package. There's also fan-funding, the pay-what-you-want model, and artists just giving away music in order to promote live performances or merchandise.

To make a success out of a release, musicians need to approach a combination of multiple vehicles in a synergistic way. All this conjecture about the future of the music industry is very tiring to me. Let's talk about what's real right this minute instead. I think it's going to stay this way for a long time to come. Whether it's good or bad for the artist...that's an interesting question. Honestly, whether it's good or bad for the artist is up to the artists themselves. You can either embrace it or sit around and bitterly complain. And there are a lot of older artists sitting around and bitching when in fact they can make all of this work for them. So you can take a lot of it into your own hands now.

There are a lot of ways to quietly or not so quietly build up your audience. I think ultimately it's a good thing. I think the major label structure has been largely negative for artists financially speaking right down to concepts like never owning your own masters, slave labor-like contracts that span decades often specifically designed to ensure that the artist makes no money from the recordings, and for their families to never benefit from them. I think the washing away of that structure is a really wonderful thing. Having said that, a lot of those labels used to do some work to help get the word out. Obviously the benefit was the distribution, and sometimes the advertising and awareness. Now that's often the responsibility of the artists themselves. So if you're willing to do the work it's a really great thing. If you're not willing to do the work you have a problem on your hands.

As far as record labels that do remain, there are some honorable ones out there in the jazz universe like Abstract Logix, Pi Recordings, and Clean Feed. I think the situation with them is that artists benefit from the aggregation of artists on that label. That creates a kind of aura where if you're part of that stable it automatically brings you a certain level of credibility or prestige. Being associated with those labels, when those CDs or downloads go out to journalists means the artists are more likely to be paid attention to. But I think you'll find with a lot of these labels that many, if not most of the artists are funding their own recording, mixing and mastering these days.

And when the label is funding the recording process, the budgets the artists are getting are much smaller as time goes by. So even if you are signed to a record label, a lot of financial management and responsibility is placed on the shoulders of the artist, and there's a lot of money for them to absorb as well. So it's almost more of a sharing arrangement with a record label as opposed to the old model where the record label was funding everything until the record came out at which point it was the artist paying back the advance through sales, hopefully, to make up for it. So it's a very different model now.

AAJ: Going back to when Innerviews first was hitting the web in the '90s, you told me you received some serious criticism from established music journalists. Can you tell me about that and how you reacted and handled it?

AP: When Innerviews came out in '94 and started to pick up steam toward the late '90s, yeah, there was a lot of criticism from established music journalists who I'm not going to name—people who were calling it a joke. They acted like it was just a fad, like this whole online music journalism thing was going to go away. They were like, "Wow. This guy is going to put out this stuff and not charge anything, and he can run stuff as long as he likes? Who does he think he is?" I did have "actual" journalistic credentials, ironically. I think, in general, that Innerviews and the other early online music magazines were probably a little bit scary for people who were wedded to the printed page, especially at the dawn of the web when it went live.

But while I had this peanut gallery of 50 and 60 year old music journalists heckling me, on the other side I had tons of artists going, "This is really cool. This is really interesting. These are really in-depth, substantial interviews. We're not sure we're going to get that level of detail or research in something that runs in some of these other things." Really, it was the artists who helped propagate Innerviews during those early days. An interesting thing to note is until around 1998, virtually all interviews for Innerviews were arranged by me contacting the artist directly and not going through managers, publicists or record labels. And that sometimes really pissed off managers, publicists and record labels [laughter]. When a major artist gave me an interview they'd be like, "You gave an interview to who? To what?" Then the interview would go up and there'd be quite a bit of positivity going, "Oh, wow. That's really good stuff."

And then around the late '90s and into the early 2000s, the site gained a lot of credibility with labels who realized, "OK. This is legitimate and this is forward-looking and this is the way things are going." And certain really important labels like ECM, Virgin Records, and even people at huge labels like Warner started awakening to the fact that coverage on Innerviews would benefit them. They started giving me interview opportunities directly through the label. A certain level of credibility kept building and building which basically eliminated the peanut gallery. Artist and audience enthusiasm are the real reasons the site ended up perpetuating, and why I kept doing it. Truthfully, those are the only opinions that ever mattered to me.

AAJ: What do you see as the future of print music journalism going forward?

AP: I think the future of major print music magazines is basically that they have no future. I used to think I was burning bridges when I said stuff like that, but now the reality is dawning on all of them. They're going to continue falling by the wayside if they do not completely reinvent the way they do things. I think there will be very little room for print music magazines going forward. There are studies pointing to the idea that the printed newspaper could largely be dead by the end of this decade. There's a website called Newspaper Death Watch chronicling the industry's demise in progress. So, if that's what they're saying about the printed newspaper, what does that mean for music publications that are a lot more niche than The Wall Street Journal? The future is not looking bright for them.

I think there could be a temporary hybrid future for the print music magazine where there's still a low circulation print counterpart to the web version. But that's not a long-term viable option. I think a lot of the energy is going toward tablet based devices like the iPad or the Galaxy Tab. And that's definitely the future of mobile-based reading, whether it's for music publications or anything else. Tony Wallace, a leading iPhone/iPad app developer and I, recently launched an iPhone/iPad Innerviews app that hit the top-20 music apps chart worldwide. So, we're pushing Innerviews forward in that way too. The other thing to consider is the demographics of it all.

Music magazines have historically been something for kids. And by kids, I mean you can take that right up to age 35. And we have generations of kids who barely even know what a physical music release is, much less a physical magazine about music. So, I think the relevance and even the names of the print magazines are going to fade significantly as people rely more and more on social media for knowledge. Who knows what's going to happen with Apple's Ping if they choose to evolve that where online purchasing is merged with actual content and artist blogs. If Ping really does get true Facebook integration, that's going to be a very, very powerful universe for information about music. Either the print magazines have to completely reexamine their approach for the new media universe or they're going to die. Simple as that.

Tags

Anil Prasad

Interview

Joe Lang

United States

Bjork

McCoy Tyner

john mclaughlin

Victor Wooten

Joe Zawinul

Souvik Dutta

Jonas Hellborg

Noa

Michael Hedges

Bunky Green

Rudresh Mahanthappa

Sonny Stitt

Ron Carter

Tony Levin

Brian Eno

Brand X

Chester Thompson

Weather Report

Jaco Pastorius

Wayne Shorter

Bill Bruford

Return To Forever

Miles Davis

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.