Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Nils Petter Molvaer: Colors, Noises and Moods

Nils Petter Molvaer: Colors, Noises and Moods

We are a small community in Norway. There is a quite strong musical tradition that doesn't have anything to do with the American music. We improvise from quite different platforms; we come from a different place.

Molvær performed recently at the 2010 Enjoy Jazz Festival in Mannheim, Germany, with Food—Thomas Strønen and Iain Ballamy—also featuring Christian Fennesz, and is preparing to record the follow-up to his well-received Hamada (Sula, 2009) with his current trio that also includes guitarist Stian Westerhus.

All About Jazz: How would you define your music, in a single word?

Nils Petter Molvær: I have spent the last 15 years trying to find that word. I would define it as: open.

AAJ: How would you describe it in many words?

NPM: I would describe it as the energy created by the tension between contrasts.

AAJ: There must have been a moment in your evolution when you realized that you are a musician and you would be doing your own thing. Can you identify that moment?

NPM: Sure. I was 16 or 17 years old, and I was working as a bricklayer, building a swimming pool. I remember that at some point I told the guy I was working with: "You know, I think that I am going to be a musician." At that time, I had some private music lessons and I was playing in a band. Shortly after that, I applied for the music school and got admitted. I was in that school for two years, together with very nice musicians. Later I went to Trondheim to the conservatory, but I couldn't get admitted because I didn't have the secondary school certificate, and you cannot do the exams without it. I was supposed to attend the classes on the side, but I never really did, and almost two years later I left for Oslo. After that, things went very fast. Soon the group Masqualero was founded, and from then on I was living from music.

AAJ: When did you start composing music?

NPM: I stared to write quite early. At first, when I was with the band in the school I started writing the instrument parts, and I wrote right from the beginning of the Masqualero. I made a song called "Remembrance," and on the second album I started to write songs, which were kind of leading to what I do now. Then a strange thing happened. One day, a very good friend of mine, [singer] Sidsel Endresen, brought me a cassette I had given her in the late '80s with music I made on the computer—I started doing music on the computer very early. I could recognize quite a few things there, and because she didn't use them I took those songs and developed them into Khmer (ECM, 1997). In those days, I also started making music for ballet shows.

AAJ: Can you follow an evolution course here?

NPM: For me personally, the work I did with a Norwegian traditional singer, who now is almost 80 years old, was very significant. I always liked rhythms and grooves, and I started to hang out in clubs and work with DJs, and then there came a time when I wanted to merge these things together. I was trying to find a form that summed it all up. And the result was Khmer. If you look at the references, you can see that I and Bugge Wesseltoft were working almost on the same thing but separately. We used to have a band in the late 80s, like a quartet, with Audun Kleive and Bjørn Kjellemyr as rhythmical section.

NPM: For me personally, the work I did with a Norwegian traditional singer, who now is almost 80 years old, was very significant. I always liked rhythms and grooves, and I started to hang out in clubs and work with DJs, and then there came a time when I wanted to merge these things together. I was trying to find a form that summed it all up. And the result was Khmer. If you look at the references, you can see that I and Bugge Wesseltoft were working almost on the same thing but separately. We used to have a band in the late 80s, like a quartet, with Audun Kleive and Bjørn Kjellemyr as rhythmical section. AAJ: And now?

NPM: The way I work now with the band is more open. What you will see tonight is totally improvised. It kind of developed naturally from the way I improvise. Now I try to work more with colors than with chords; I work with noises and moods. I make skeletons which I can interact with. Do you know what I mean?

AAJ: Yes, you can hear it! What factors have defined your style and your choices?

NPM: A significant reference leads back to the beginning of the '80s. In that time, I wasn't listening to much jazz. I was somehow tired of the trumpet, and I was playing kind of hard. Then I heard the duduk players, the shakuhachi players, also Jon Hassell the trumpet player, and that was like a revelation for me. Then I started working with the traditional Norwegian singer I mentioned before, and he told me how he experienced things.

So at one point, instead of hiding the trumpet, I began working with it on this new basis. I didn't want to sound like anything else. I didn't want to sound like a saxophone and I didn't want to show off; what I wanted to create was more like a voice. Technique can be beautiful, but for me it was more important to create a voice. A voice can be soft, but not only that: it can be angry, crazy, frustrated, whatever. And then I heard the ney flutes from North Africa and Central Asia, and the sounds from Armenia, Bulgaria and Romania—very beautiful sounds. All these traditional sounds affected me much more than jazz. I also listened to a lot of Brian Eno, and I found those things quite fascinating.

AAJ: Have you been consciously working on your tone or it did it come up naturally? Miles Davis once said that after he'd been down and out, he needed three years to get his tone back.

NPM: I can work on it, of course. It is a matter of what you want it to sound like, and then you try to focus on that and use the appropriate technique. For me now, it is more of an organic thing. It is my voice. There are managers who try to make you sound like something else, and I always tell them that it is not possible. Actually the whole process is more a matter of finding your own voice than of building it consciously.

AAJ: Nordic jazz has developed tremendously, especially during the last decade, and today contemporary jazz music is no longer conceivable without this dimension. Do you have an explanation for that?

NPM: I can speculate. You know, we are a small community in Norway; it is kind of transparent. We are all involved in small projects with traditional musicians, classical musicians, and noise artists. And then there is a quite strong musical tradition that doesn't have anything to do with the American music. I enjoy the music coming from there, but we improvise from quite different platforms. They improvise from swing, from standards, from the musicals of the '20s. That is all fine, but we come from a different place. I don't know how it evolves and why it develops in the way it does, but then again, there is no competition. It is a very open community, or at least I feel it that way, and you work with all kinds of musicians who create their own synergy.

AAJ: What would you identify as characteristic for Nordic Jazz?

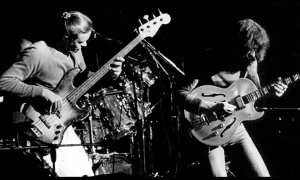

NPM: Musicians like Jan Garbarek, Terje Rypdal and Jon Christensen took swing away from more straight jazz without being totally conscious about it, but I think that they have mainly shown that it is possible.

AAJ: Many people say that if something doesn't swing or groove, or is not black music, it is not jazz. What is jazz for you? Do you see it as a restrictive term?

NPM: Jazz is everything from Louis Armstrong to Cecil Taylor. That's a very big step, in a way. For me, the minute you start putting it into a category, you actually box it in. I think that most musicians want to be in a different place. I don't talk about my music as jazz; I just leave that to others. For me, jazz has to do with interaction and improvisation and what you improvise from is not so important as long as it is rooted in something real. Jazz for me is a platform from which I can improvise. Sometimes what we do is in many ways older and freer than what most Americans players do.

AAJ: Are you aware of the impact this group of jazz musicians had on the evolution of European jazz? Would you like to comment on that?

NPM: I don't know, actually. I think about it, but as I musician I can't see it so well. I can see where we started, and that now we are traveling around the world playing, people like it. But what I try to do is focus on the music. This question is something for the critics or journalists, I think.

AAJ: The rhythmic pattern, instrument processing and the long tones that you have so successfully influenced and developed render a certain hypnotic or ritual quality that sets the public in a state similar to trance. Do you think that this corresponds to an intrinsic musical evolution or that it also has a social implication?

AAJ: The rhythmic pattern, instrument processing and the long tones that you have so successfully influenced and developed render a certain hypnotic or ritual quality that sets the public in a state similar to trance. Do you think that this corresponds to an intrinsic musical evolution or that it also has a social implication? NPM: What I try to do in every concert is to create a state where you simply exist, then and there. I wouldn't call it being in trance, but rather being in the stream. But on the other hand, yes, you are right; I think that people need that particular flow of energy in order to let go of the quotidian and their daily worries. It is a bit like looking at something beautiful or like having sex; you just let go. I think it is a give-and-take situation people need to experience more these days.

AAJ: Now that you are mentioning the energy flow, what happens when you close your eyes and there's just music around you, and you are there with your instrument? What are you thinking about in those moments? Is that something you can describe?

NPM: I close my eyes in order not to have any distraction but the sound, and also in order to concentrate fully on what I am doing—to go with the flow, to find the path. For me, it is more like not thinking at all; it is more like a state of meditation that helps you center yourself.

AAJ: Do you have communication with the public then? Can you tell the difference from public to public?

NPM: Absolutely! That's when you communicate best. You can tell the difference by the vibrations, by the energy that is set in motion. It is the same thing when you meet an individual. You can tell right away if they have a good energy. It like a big, organic thing and you can tell right away if there are good vibrations or not. And if it is really, really good, you always remember it.

AAJ: As you are touring the whole world—you are just coming from Strasbourg and are heading for Spain and then Poland—do you sense a difference in perceptions? Are there regions that you would define as warmer than others?

NPM: Sure. By the way, the Poland tour just got canceled because it looks like the promoter ran off with the money. But yes, there are quite a few warm areas on the map. There's a club called Roxy in Prague that comes to my mind, and there's a small place in Poland I remember very well, also most places in Germany are very receptive to our music, like here at the Enjoy Jazz festival.

AAJ: Germany has remarkable public support for all musical genres, maybe because Germans are such a melodic people.

NPM: True. In general, the countries from Eastern and Central Europe also have a very open approach to our music and a very open attitude. We just had a tour in the Middle East and there's a fantastic place in Istanbul called Babylon—a very picturesque location too. The place is always full and emanates very good energy.

AAJ: Why those countries?

NPM: I think the reason is that they have been part of a closed system for such a long time and now, when they have opened up, they are fresh and hungry for new things as compared with New York or Paris, where there is such a strong tradition and where people, so to speak, grew up with jazz.

AAJ: Last year you performed at the Garana Jazz Festival in Romania. What was your impression?

NPM: Garana was fantastic—an incredible place. There was a huge storm, but the whole atmosphere was magical. They have a very good public there.

AAJ: What has been the biggest place you have performed at so far? How big can a place get for jazz?

NPM: I think the biggest would be the open-air show in Karlsruhe, called Das Fest, where we had 60,000 people.

AAJ: You are quite active doing film music. In what way do you interact? Are you illustrating?

NPM: I try to find something that sort of encapsulates the soul of the character. I would rather say that I am amplifying. When you have a landscape you can illustrate it, but when you do real music you try to go in and be the soul of the character.

AAJ: When is a film good? Is it when you remember the music or when you don't?

NPM: I think that both the film and the music are good when you remember the main theme. Have you seen Dances with Wolves (1990)? I didn't really like the score there. What I like are the scores in Spielberg's movies—think about the theme in Jaws (1975)—or Stanley Kubrick films. Do you remember the theme in Eyes Wide Shut (1999)? And then you have those fantastic, beautiful themes like in Deer Hunter (1978), or the music of Ennio Morricone or Goran Bregovic. If you come to think of it, generally in movies there are very few themes that try to amplify the soul; most of the time it is mere illustration.

NPM: I think that both the film and the music are good when you remember the main theme. Have you seen Dances with Wolves (1990)? I didn't really like the score there. What I like are the scores in Spielberg's movies—think about the theme in Jaws (1975)—or Stanley Kubrick films. Do you remember the theme in Eyes Wide Shut (1999)? And then you have those fantastic, beautiful themes like in Deer Hunter (1978), or the music of Ennio Morricone or Goran Bregovic. If you come to think of it, generally in movies there are very few themes that try to amplify the soul; most of the time it is mere illustration. AAJ: Famous last question: plans and projects?

NPM: I try to stay healthy, take care of my body and my brain now that I am over 50, and enjoy being with my kids. In the first half of January, I am going to develop some ideas in the studio and start working on a new album. If all goes well, it will come out in the autumn or maybe even earlier. I am going to do music for two movies, one of them for a Polish project, and I have quite a few tours next year.

AAJ: Are you working alone?

NPM: I am working partly alone but also with my new guitarist, Stian Westerhus. We'll see what comes out of it. We want to keep it open.

Selected Discography

Food, Quiet Inlet (ECM, 2010)

Nils Petter Molvær, Hamada (Sula, 2009)

Nils Petter Molvær, Re-Vision (Sula, 2008)

Nils Petter Molvær, Remakes (Sula, 2005)

Nils Petter Molvær, er (Sula, 2005)

Nils Petter Molvær, Streamer (Sula, 2004)

Nils Petter Molvær, NP3 (Emarcy, 2002)

Nils Petter Molvær, Solid Ether (ECM, 2001)

Nils Petter Molvær, Recoloured (Emarcy, 2001)

Eivind Aarset, Light Extracts (Jazzland, 2001)

Nils Petter Molvær, Khmer (ECM, 1997)

Bugge Wesseltoft, New Conception of Jazz (Jazzland, 1997)

Marilyn Mazur/Future Song, Small Labyrinths (ECM, 1997)

Masqualero, Re-Enter (ECM, 1991)

Sidsel Endresen, So I Write (ECM, 1990)

Masqualero, Aero (ECM, 1988)

Masqualero, Band à Part (ECM, 1985)

Masqualero, Masqualero (ODIN, 1983)

Photo Credits

Page 1: Madli-Liis Parts

Page 2: Christian Gaier

Page 3: John Kelman

Tags

Nils Petter Molvaer

Interview

Adriana Carcu

Food

Thomas Strønen

Iain Ballamy

Christian Fennesz

Sidsel Endresen

Bugge Wesseltoft

Audun Kleive

Jon Hassell

Brian Eno

Miles Davis

Jan Garbarek

Terje Rypdal

Jon Christensen

Louis Armstrong

Cecil Taylor

Marilyn Mazur

John Kelman

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.