Home » Jazz Articles » Profile » Fred Anderson: 1929-2010

Fred Anderson: 1929-2010

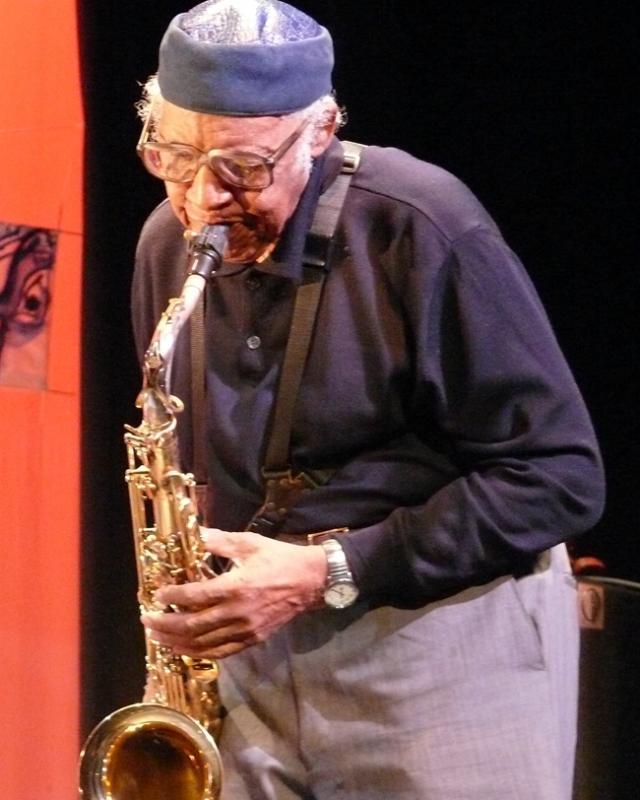

There aren't many artists with so singular a vision as that of late Fred Anderson, who died June 24 at the age of 81. There are fewer to be certain if the list is restricted to members of that exalted and nebulous class called "masters." It's a word that, in jazz, gets thrown around a little too casually. A master composer might excel at writing for string quartet as well as symphony. A master musician might be fluent in a variety of instruments. But a mastery like Anderson's is harder to quantify.

There aren't many artists with so singular a vision as that of late Fred Anderson, who died June 24 at the age of 81. There are fewer to be certain if the list is restricted to members of that exalted and nebulous class called "masters." It's a word that, in jazz, gets thrown around a little too casually. A master composer might excel at writing for string quartet as well as symphony. A master musician might be fluent in a variety of instruments. But a mastery like Anderson's is harder to quantify. For much of his career, Anderson's work went in one direction, his muse speaking a single language. He was beholden to the heroic stance of the 1960s, to the powerful black men with saxophones in hand, to Ayler and Coltrane and Shepp and Sanders, his contemporaries even if his own fame would come much later. Within his hard-edged playing, echoes of that era were more than apparent. But so were the influences of Charlie Parker and Coleman Hawkins and Sonny Rollins. Buried in the flurries were decades of history. Variations from the theme—his sometimes placid recitals with pianist Marilyn Crispell, for example, or the blues heard on the 2003 Delmark release Back at the Velvet Lounge, only underscore his usual drive. So focused was his art that even when, in 1997, he released a record called Chicago Chamber Music, it was his kind of chamber: two CDs of driving, sax-trio jazz.

And of such a singular purpose was he that the attachments of being a jazzman—touring, recording—didn't seem to concern him. He was proud of his accomplishments, but was ever humble, even tending bar on the nights of his own gigs. When in 1982 he bought the Velvet Lounge, the Southside Chicago club where he had been bartending, he seemed to have everything he could need: a means of income and a place to play. At age 53, an international reputation didn't even seem on the horizon. Outside Cook County his name would barely be known for another decade.

It was in no small part through the pull of New York City and the Vision Festival that he would at last find the career he deserved. Over the last decade he became a fixture at the festival, and was scheduled to play there June 24. Although a stroke had already incapacitated him, it was the morning of that scheduled appearance—during an evening honoring fellow Chicago jazz groundbreaker Muhal Richard Abrams—that Anderson passed away.

The newfound fame he was able to enjoy for the last decade of his life began with a remarkable band simply billed with its members' names: Fred Anderson, Hamid Drake, Kidd Jordan and William Parker. The group cemented a number of significant relationships in hard jazz. It established Drake and Parker as one of the most in-demand rhythm sections on the scene, it introduced many listeners to the kinship between Anderson and Drake (as a child in Louisiana, the younger Drake lived in the same building as Anderson and would hear him practicing saxophone through the walls), and it introduced many listeners not only to Anderson but to another under-recognized elder, Edward "Kidd" Jordan. The 2000 double-CD 2 Days in April (Eremite), remains an essential title in the the current era of free jazz.

Although in name and philosophy he was a member of Chicago's Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians—the seminal organization co-founded by Abrams in the '60s—Anderson was never among its most active members. He was at least as much a practical uncle as a spiritual godfather. George Lewis, in his essential history A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music acknowledges Anderson's significance as a role model, even if he wasn't central to the association itself. By the 1980s, he writes, Anderson was "becoming a hero to the younger generation, a symbol of the combination of personal tenacity, historical continuity, and radical musical integrity that many younger Chicago musicians, both within and outside the AACM, were inspired by. One reason for this respect was the Chicago community's perception that Anderson had continually sought to put into practice AACM tenets of self-reliance and independence."

Anderson gave the AACM one of the things it needed most; he gave the players a stage. Two, in fact, and another thing Anderson might not have expected to see 25 years ago was a new home for his Velvet Lounge. In recent years, he went from owning a tavern to a nightclub, complete with blue lights and framed photographs on the walls, a proper space and a testament to his importance to the city. But the old Velvet, the space he lost due to the Southside gentrification that began with the 1996 Democratic National Convention—that was a home. The room was barely lit by an oversize and inelegant chandelier, but the large stage was brightened by wallpaper, a sort of combined Kente and floral pattern. On one side of the stage hung a Billie Holiday poster, still shrinkwrapped and pressed against the cardboard it came in, on the other an illuminated Coors clock. (Both clubs, as well as Anderson in action, can be seen on a pair of fine Delmark DVDs: the old on Timeless: Live at the Velvet Lounge and the new on 21st Century Chase: 80th Birthday Bash, Live at the Velvet Lounge). On nights after the Chicago Jazz Festival, a line would extend from the side of that stage with Jordan, David Murray, Edward Jr. Wilkerson, Ari Brown, Mwata Bowden, Ernest Dawkins and a host of saxophonists, horns in hand, patiently waiting there turns. It didn't smack of being a class joint, but it was sacred ground.

The old Velvet was Anderson, and as a result it wouldn't have survived him. The new one is a proper space, the sort of spot needed, in a society without distinctions between art and entertainment, needed to authenticate the viability of art on the edges of the marketplace. As much as his discography, the little nightclub on the Southside will be his legacy. In lieu of flowers, Anderson's family has asked that donations be endorsed to AIRMW with a memo that it is for the Velvet Lounge Fund and sent to Asian Improv aRts Midwest, c/o JASC 4427 N. Clark St. Chicago, IL 60640. All proceeds will go to support keeping the Velvet Lounge open and thriving into the future.

Photo Credit

Frank Rubolino

Tags

Fred Anderson

Profiles

Kurt Gottschalk

United States

Charlie Parker

Coleman Hawkins

Sonny Rollins

Marilyn Crispell

Muhal Richard Abrams

Hamid Drake

Kidd Jordan

William Parker

George Lewis

David Murray

Edward Wilkerson

Ari Brown

Mwata Bowden

Ernest Dawkins

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.