Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » Either/Or (No More)

Either/Or (No More)

You know that party game where you present people with a forced choice that's actually a litmus test for distinguishing between two kinds of people? Here, let's play—pick one (and only one): Matisse or Picasso? Federer or Nadal? The Daily Show or The Colbert Report?

You know that party game where you present people with a forced choice that's actually a litmus test for distinguishing between two kinds of people? Here, let's play—pick one (and only one): Matisse or Picasso? Federer or Nadal? The Daily Show or The Colbert Report? Since I am a "jazz composer" by training and self-identification, it seems like I'm always being asked to play this game: improvisation or composition? I am not alone in this—every composer who allows the element of indeterminacy to inflect their music has to grapple with the tension between these two forces. But ever since I reluctantly left behind my former life as a jazz pianist in order to concentrate on composing for my own big band, I find I've become (perhaps unsurprisingly) a lot more reflective about the role improvisation plays in shaping my music.

A big part of the reason why I shifted my focus from playing to composing is that I came to realize that I don't actually have a deep-seated attachment to improvisation itself. I realize this sounds like a horrible, shameful admission—"ohmigod, how can you possibly say that? Don't you understand that improvisation is what jazz is all about?" But see, the thing is, what matters to me is music, not process. I don't care how someone gets there, just so long as they get there. Plus, at the risk of stating the obvious, there is an abundance of brilliant and meaningful music in the world that involves no significant improvisational element. (I'm certain you have some on your iPod.)

Instead of instigating an identity crisis, the realization that I didn't believe in improvising for its own sake led me to think more carefully about what improvisation is actually good for. What can an improvising musician (or, better, what can this improvising musician) do that I can't do as a composer? How can I create a setting that is conducive to the specific kind of improvisation I'm looking for?

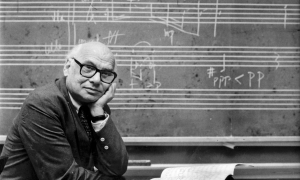

Once I freed myself from the obligation to "leave room for blowing" (or for spontaneous thematic development, gesture-directed collective shaping, extemporaneously-determined form or what have you)—I felt oddly liberated. Improvisation became a strategic choice instead of a habitual one. I deployed it only where the music seemed to demand it. I began to understand what Bob Brookmeyer had tried to impress upon me in our lessons: "The solo should only happen when absolutely nothing else can happen."

So naturally, the first track on my debut recording as a composer-bandleader, Infernal Machines, opens with 45 seconds of unaccompanied improvisation.

Okay, before you sigh and roll your eyes: that electronically-processed cajón solo at the top of the cut in question, "Phobos," happens because there is absolutely no other way to begin that tune. Honest, I swear! It turns out that allowing space for improvisation out front is the best way to introduce the unusual sound-world of the piece and to establish a subtle sense of foreboding before the notated music begins. I could have instead opened the piece with a densely-notated electro-cajón showpiece for drummer Jon Wikan, but then we would lose the feeling of the music being generated spontaneously from an initial spark. And Jon intuitively understands how to transition seamlessly from his open improvisation into the written music.

Later in "Phobos," after introducing and developing the composed thematic material, we reach an arrival point that fairly screams to be followed up with some kind of improvised solo—specifically in this case, Mark Small's tenor sax. But this is the most hazardous part of the piece, the point where we are most in danger of losing the thread and veering off into a conventional blowing-over-changes sound. After experimenting with a few different approaches, I found the best solution was for me to cue each chord in the progression, one by one. This allows me to keep my composerly hand in the game by shaping the harmonic phrasing in real time—some chords might last 11 bars, some might last 3 and so on... it varies every time we play it. This keeps Mark on his toes, forcing him to adapt on the fly if I happen to cue the next chord change in a different spot from where he wants it. But that slightly unsettled feeling is exactly what's needed at that point in the music. A lot of jazz musicians would chafe at these constraints, but I'm fortunate enough to be able to work with players who can channel their creativity towards the needs of the music, usually without an excess of scenery-chewing.

Later in "Phobos," after introducing and developing the composed thematic material, we reach an arrival point that fairly screams to be followed up with some kind of improvised solo—specifically in this case, Mark Small's tenor sax. But this is the most hazardous part of the piece, the point where we are most in danger of losing the thread and veering off into a conventional blowing-over-changes sound. After experimenting with a few different approaches, I found the best solution was for me to cue each chord in the progression, one by one. This allows me to keep my composerly hand in the game by shaping the harmonic phrasing in real time—some chords might last 11 bars, some might last 3 and so on... it varies every time we play it. This keeps Mark on his toes, forcing him to adapt on the fly if I happen to cue the next chord change in a different spot from where he wants it. But that slightly unsettled feeling is exactly what's needed at that point in the music. A lot of jazz musicians would chafe at these constraints, but I'm fortunate enough to be able to work with players who can channel their creativity towards the needs of the music, usually without an excess of scenery-chewing.Paradoxically, it was only after I stopped treating improvisation as something that has to happen that I began to figure out how to harness it effectively and integrate it into the big picture. I developed a keen appreciation for the various ways in which improvisers can be guided, nudged or prodded into coming up with ideas that will advance the musical narrative or steered back on track when they are on the verge of taking the entire piece off the rails. It starts with musicians who are more interested in storytelling than showboating. But as a composer, it's up to me to write music that will draw out those aspects of an improviser's identity that I need in order to tell the kind of story I want to tell. When it works, the composition shapes the improvisation and the improvisation completes the composition and no forced choice can pry them apart.

Tags

About Darcy James Argue

Instrument: Composer / conductor

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Darcy James Argue Concerts

Mar

5

Thu

Brad Mehldau with the HR Big Band @ hr-Sendesaal

Hr-sendesaal - Hessischer RundfunkFrankfurt am Main, Germany

Mar

14

Sat

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.