Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Eric Harland: Searching the Patterns in Life

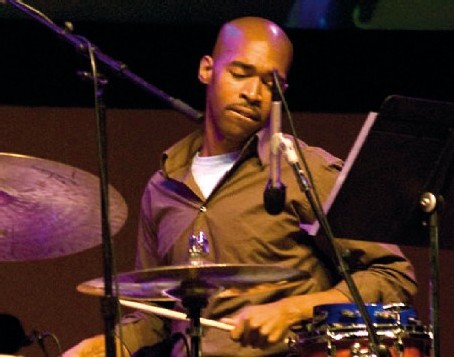

Eric Harland: Searching the Patterns in Life

But then, in a way, this was foretold by an eight year-old Harland to his mother.

"She said I told her I would travel the world, meet a lot of girls and play music," he laughs. "The funny thing is, I would say that has been my life for the last few years (except for the girls). It's all be fun; it's all been good.

"I will say that as a kid, I really had a focus about it," Harland adds. "I can't say I put things on the wall that said, 'Have a great day—you're going to be a great musician.' I just took it a day at a time, I just knew I loved music and I just wanted to be the best I could be at whatever I was doing. And all of a sudden, I woke up and it was happening."

That summary glosses over a few bumps along the way for Harland. Though he was a drumming prodigy as a teenager in Houston, Texas at the High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, where Wynton Marsalis encouraged him to continue his education in New York in 1993, after hearing him play. Harland followed the advice, receiving a full scholarship to the Manhattan School of Music.

His special citation from the International Association of Jazz Educators for Outstanding Musicianship in 1994 further raised his visibility, making his childhood prediction look very prescient.

"Starting off, I was really fortunate to have a really, really good private drum instructor [Craig Green], who kind of got me between five and eight," Harland says. "And I went to this performing arts middle school and he was the instructor there.

"After that, he just kind of gave me guidance and in high school, it was kind of words of wisdom," he adds. "But he's always been a really, really good, really patient, really great instructor. He's very different, I would say, than any instructor I've come in contact with since then."

Harland notes Green's methods relied on cultivating his students' own skills as much as inculcating specific technical chops.

"But he's very patient," Harland says. "He doesn't have you do basic patterns, he just kind of patiently guides you so you can learn to do it correctly. It just really helped.

"If anyone doubts the skills he's taught ... you think about all the great drummers that have come out of Houston—you got Chris Dave, you got Kendrick Scott, you got Jamal Williams," Harland continues. "We all come from Mr. Green. It just shows what a phenomenal teacher he is—and if you thought it was just because of drums, his daughter happens to be a really, really tremendously excellent violinist.

"So, it just shows his teaching skills, his method of teaching actually works," Harland explains. "He is such a simple guy, he doesn't want anything, he just loves music, he loves the drums. He loves working with people."

After landing in Manhattan, Harland's professional career started out strongly but his first taste of independence led to a downfall.

"When I got to New York, and of course, as a young guy coming from Houston to New York, I kind of went crazy and I had a great time, I did everything I could do," Harland concludes. "And that was great. I didn't have any issues with what I was doing—but my mom did! My mom was, like, 'this isn't right.'"

Harland explains that his mother, firmly entrenched in the Baptist Church, would occasionally rebuke him, warning him that God was watching him.

"And that that kind of scared me when bad things started to happen," he says. "At first, good things were happening and then at a certain point bad things started to happen."

"And that that kind of scared me when bad things started to happen," he says. "At first, good things were happening and then at a certain point bad things started to happen."One of the most important things happening to Harland personally was a tremendous loss of weight. As a teenager in Houston, Harland was overweight and often left out of social circles in high school. During his first years in New York, he began losing weight, dropping from 380 pounds down to 160.

"I went through a point of being kind of malnourished, and when you're malnourished, your blood sugar is low and your body is very sensitive to everything," Harland explains. "I remember being at my wits end, coming back home after this one show in Milwaukee, and I passed out because I hadn't eaten.

"And my mom had to come get me from Milwaukee and she is like drama queen," he adds. "She thought on the plane, that I had died and that she prayed and I came back to life, and I was just like, 'Wow, OK.' So I got home and she said I got to give my life to Christ, blah-blah-blah, so I did it."

"And so I didn't really know what to think, and so at that particular time, that was the only kind of concrete thing that really spoke to me was Christianity, religion," concludes Harland.

So Harland gave up the jazz life, returned to Houston and enrolled in the Houston Baptist University College of Biblical Studies and became an ordained minister.

From left: Zakir Hussein, Charles Lloyd, Eric Harland

From left: Zakir Hussein, Charles Lloyd, Eric Harland"So I gave my life over the Christ, and I went to church and I kind of got renewed through that and it really helped me," he s.ays "Everything made sense and I just told myself, 'I can get onboard with this.'

"I began to preach the Gospel of Christ, I learned a lot about the Bible, everything about the Bible made sense, I started understanding the history of the Bible and I was like, 'This is really great,'" explains Harland.

But instead of being the end of his spiritual searching, Harland's studies and ordination fueled an ongoing journey he's still exploring.

"I'm cool with who I am and what I am—and that's the key," he says. "It's not about following a rule book or someone else's rules—I've kind of come up with my own. Everything has a cause and effect. For me, it just seems to be evolution."

That evolution led him back to the drum kit. The matured Harland returned to New York and built a reputation as a solid and inventive drummer on a series of studio sessions. After recording on saxophonist Greg Tardy's appropriately named Serendipity(Universal, 1998), Harland appeared on pianist Aaron Goldberg's Turning Point (J Curve, 1999) and trumpeter Terence Blanchard's Wandering Moon (Sony Classical, 2000).

Since then, it's been a torrent of dates and tours, working with Kenny Garrett, Greg Osby, McCoy Tyner, Joshua Redman, Stefon Harris, Dave Holland and others. He's a member of the SFJAZZ Collective (San Francisco Jazz Collective, was tapped for the 2007 Monterey Jazz Festival quartet, and has been touring with Charles Lloyd.

And in 2006, he toured with Lloyd and Indian tabla master Zakir Hussain, stretching Harland's musical chops further. The concerts included improvisations moving Harland from behind the drums to piano and keyboards, and to create rhythms matching the elements of Hussain's playing.

Listening to the trio's live recording, Sangam (ECM, 2006), Harland's inventive fills and melodic playing loom large. He said he thought about how to work within the shifting rhythmic patterns found in Asian drumming.

"I remember riding around in Pakistan with this student, and I was just tapping my hands, you know, and he said, 'You're playing sevens—do you often play sevens,'" Harland says, referring to the repetition of patterns in a rhythmic cycle. "And I was hadn't even thought about it, and then I realized that, yeah, I was."

"You know, in India, they have this involved and formal system of rhythms they use, and some are sevens, some are 12s. But they grow up using them and it becomes second nature to them, so they just think like that," he explains.

Harland also says that the experience was an eye-opener that further expanded his appreciation of drumming and rhythms.

"I pretty much learned from everybody, that's the way I like to look at," he says, noting that he eschews formalized training, finding it off-putting and stilted.

"I've watched how they do clinics and things and every body gets so wired about things—it's like, 'You gotta do this' and 'You gotta do that,'" Harland says. "I don't respect the teacher who stick to books and doesn't pay attention to the students that they have in class.

"I've watched how they do clinics and things and every body gets so wired about things—it's like, 'You gotta do this' and 'You gotta do that,'" Harland says. "I don't respect the teacher who stick to books and doesn't pay attention to the students that they have in class."Now I understand for a lot of kids, you have to have a system," he adds. "It makes sense but at the same time, there has to be a way to develop a system that you don't have to try to keep this order because something for the sake of order you lose this organic feel to it."

At this point in his spiritual journey, staying in the musical moment, keeping it real, is vital to Harland. He's been experimenting with compositional techniques in search of finding the most creative, in-the-moment moments for his music.

"I think about the techniques; I think about the chords; I think about the form, about the format; about the structure—but at the same time, sometimes, I try to just try to shape a tune around just a melodic line," says Harland. "And then this new thing, because of the technology we have, I've started to take a line and a bunch of times, just writing a bunch of random notes on a score and seeing what it sounds like. You know, writing random rhythms at the same time. And then you come up with very open, unique sound—it gives a different point of reference.

"And then you allow your artistic creativeness to really come to the forefront because you're really hearing something, you hear something that hasn't been done," he adds. "What I do then at that point, is to adjust the notes or the rhythms accordingly to try to find a tonal center or a key—try to find a melody in the chaos.

"That's another creative tool that I'm sure tons of people use—they don't talk about it much, but they have to because it's so great, why wouldn't anyone?," says Harland . "It's like you write a bunch of dots on the wall, then what you do is bring out the ruler and start connecting them so then people tend to look at them and go 'Wow, you really had a different approach on the placement.'

"I mean, you know, sometime they see like a certain kind of brilliance in it because it's thinking outside the box, but you have the organic and the structure," he continues. "I think that's what truly brings genius—like a person that has both nature and science because the two are pretty much the same. But I guess, of course, how we are as humans, we've created the distinction between the two. You've got people that lean towards the spiritual side or to the a more analytical, scientific side. And so when you can get both, have the similar kind of presence within the moment, that's when you achieve this ultimate kind of creation.

"I think if you think about everybody you love, they pretty much possess to a certain degree, both," explains Harland. "Like you won't hear anyone dis' Trane [John Coltrane] and I think that's because back then, he was so overwhelming. And it wasn't because he lacked anything, he was just overwhelming, just too heavy. But he had both—he could analyze every chord, he could play every scale—at the same time, he just be completely free and organic. And be very spiritual."

Harland also tries to maintain the same free-spirited approach to his ensemble, which includes pianist Taylor Eigsti, guitarist Julian Lage and bassist Harish Raghavan. The group has live recordings made in France in 2008 Harland hopes to see released in 2010, but he's also been trying his new compositional ideas with the group.

"I just want to give [the music] more space, to go into the studio and just lay down whatever I feel at the moment and just know it comes from whatever I feel myself," he says. "I'm definitely doing that with my band now—I don't actually write full tunes. I'm at the point now where I've always felt like everyone would get to the end of the tune and that's when they felt like they're ready to play the tune.

"The part of music I loved the most was always about the end of the tune because all of a sudden everyone's being creative because before then, everyone's reading the charts and the changes, trying to do this, and at the end of the tune, it's like, 'Oof! Made it ... Thank you! Thank you. I get the bronze medal,'" Harland explains. "Then, it's just like all of a sudden they'd be on this jam, they'd be on this subtle vamp of the tune, and I'm saying, 'yeah, that's the shit.'

"So I've just been writing these things to get them going," Harland continues. "That what it is performing—you may have some shit you want to say, so I'm writing so everyone gets a chance to express themselves."

And he's working on a project he's calling "Messiah Complex"—the name of the project stems from Harland's view everyone has a desire to be recognized in some way, to be a "messiah" for another person or other people.

"Everyone has this thing burning inside us—it might not be for the world, it might be for the people around you, but you want to do something special," explains Harland. "It might sometimes get misconstrued but we have this purpose. I tried to pick nine different people that I felt like had nine different lives—I mean me, Taylor, Julian, Harish, and then I think about my wife and her friends.

"I really feel that's going to be interesting because I'm actually going to get to work with my wife and friends of hers because my wife is into musical theater," Harland says. "I want to tie musical theater to jazz because there are some really great songs in the theater. There are a few songs in that genre I want to use in jazz."

Harland doesn't cite many influences but says he tries to listen to everyone—or at least, all who have a sincere message to communicate.

Harland doesn't cite many influences but says he tries to listen to everyone—or at least, all who have a sincere message to communicate."I have a hard time internalizing information from other people—I think that comes from a long way of just having a lot of dictation in my life from religion," says Harland. "When people start coming to me with information—I guess it all depends on tone. 'This is what you need to check out'—I'm kind of rebellious in the beginning, definitely, but eventually I'll go check it out because I believe that everyone has [something to say] ... Charles Lloyd's wife is making this great documentary on him, and they did this great interview, where he said, 'He has some knowledge, and she has some knowledge ...' and it just made so much sense. It just made so much sense—everyone has some knowledge. So I take that point.

"So growing up in music, because when I came to New York, I came with this crazy style so a lot of people did have something to say," Harland says. "So, I always had it in my mind; it didn't kind of veer me in any directions I didn't want to go. I got a lot of information from a lot of people; I got a lot of information not from what people would say but from how they acted, because that was something you couldn't use words to describe; you only had to be there to witness.

"So growing up in music, because when I came to New York, I came with this crazy style so a lot of people did have something to say," Harland says. "So, I always had it in my mind; it didn't kind of veer me in any directions I didn't want to go. I got a lot of information from a lot of people; I got a lot of information not from what people would say but from how they acted, because that was something you couldn't use words to describe; you only had to be there to witness."Because I always felt words can be manipulated, and because everyone's trying to be [careful] speakers, you never know if it's organic and coming out of a person or if it's something that's more practiced," Harland continues. "So for me, someone's body language is organic; you can work on it, it's still you. So I just tended to trust more in the way people would behave or the sounds in their music and then the feeling I would get from being in their presence. I think at times, you can still tell if it's real or [not] ... if it's more organic. I just tended to trust more in the way people would behave and then the felling that I would feel in their presence. I think you can at times intuitively feel whether a person is natural or not. So I kind of lean more towards ... people who had that feeling because I really felt they had some kind of divine wisdom.

"It's like from people like Greg Osby, I love just watching him," Harland says. "I love Terrence Blanchard—I think he's one of the most sensitive cats. I would see him after shows and he'd excuse himself backstage and be in tears. I'd just be like, 'Goddamn,' you know? I can really, really appreciate that kind of shit. And then I've been around other people who love to analyze—like Joshua Redman, he has it mapped out, he has it shaped. It's all these different methods I'm learning about.

"Then there's all these people I haven't had a chance to work with," he adds. "And like Pat Metheny—I love Pat Metheny but the stories I hear scare the shit out of me. But people who have worked with Pat Metheny have this divine thing to say about how everything works out. There must be something."

Harland recalls a story he'd heard about saxophonist Stan Getz, who would turn to players on the stand a yell at them to get more emotional performances.

"I think it does create a certain emotion," he says. "Miles [Davis] was like that—he just looked like he was not enjoying that shit. I look at it as just being a trumpet player, because trumpet players are just mean—I think it's because their instrument is so unforgiving. It amazes me the people that can withstand it; it's a great journey to be around—they (trumpet players) have great stage presences but at the same, if you need any gratification about what you're doing on stage, that's not going to happen. Piano players will give it up, but not trumpet players."

Harland listens to drummers also, but not always to catch particular patterns they may use.

"I like everybody for different reasons," he says. "I like Brian Blade because I feel like he represents, not so much the technical side of the drums, but more of the innocence of the drums. You know, he has such an innocent spirit and whereas, he lets you know it's OK to do it this way. Like sometimes most drummers have this thing about you have to have such complexity with the instrument just to show your technique basically, 'I got tremendous technique, so check me out.' Where Blade doesn't get into the technique thing at all, it's more like 'this is what I do' and 'this is what I'm gonna do' and it's great.

"And then I like Jack DeJohnette for the same reason, it's just so—I mean Jack will actually go for the technical stuff, it's just that his technique is just not so typical," Harland explains. "He has his own technique and style to play the drums. I love watching how he wields certain things off the drums. So he brings a whole other energy that he's really feeling the drums like an acoustic instrument.

"But then I love the technical players as well," Harland continues. "I love guys like Chris Dave, who just has phenomenal technique, and Dennis Chambers. These are Mostly fusion technical-kind of drummers that everybody knows. But keeping it in drum history, it would be like the difference between Tony Williams and Elvin Jones—I mean, sometimes you listen to Elvin and you're like trying to figure what is he playing. But it really feels good—the pulse is there; everything you expect from the drums are there. But, you know, he doesn't provide a lot of clarity between the beats. There's all this independence; there's more of like this rumbling ball that's rolling at you. And Tony Williams is like a ninja, he's so precise. He's freely making his markings, he's just such an accurate drummer and I think that's why he's such an influential drummer on almost every drummer."

"But then I love the technical players as well," Harland continues. "I love guys like Chris Dave, who just has phenomenal technique, and Dennis Chambers. These are Mostly fusion technical-kind of drummers that everybody knows. But keeping it in drum history, it would be like the difference between Tony Williams and Elvin Jones—I mean, sometimes you listen to Elvin and you're like trying to figure what is he playing. But it really feels good—the pulse is there; everything you expect from the drums are there. But, you know, he doesn't provide a lot of clarity between the beats. There's all this independence; there's more of like this rumbling ball that's rolling at you. And Tony Williams is like a ninja, he's so precise. He's freely making his markings, he's just such an accurate drummer and I think that's why he's such an influential drummer on almost every drummer."Harland says that for him, learning to communicate with the musicians he's on stage with is more crucial than demonstrating his considerable prowess with the sticks.

"It's like trying to add more to my plate," he adds. "And then when I feel like I've gained that confidence, then I can take more liberties, which what I pretty much always want to do from 'jump.' Sometimes, if you take many liberties from the beginning, it never allows people to settle, like people always feel kind of uncomfortable playing with you, and I never want people to feel like I'm always out to always play for myself. So I always take a pretty mild approach in the beginning still trying to find something unique.

"But it's always a challenge every time because everyone feels the beat different, everyone's time is different, everyone's concepts are different—it's a lot to think about," he concludes. "But at the same time, it's always a beautiful experience because it's going to be something at the end of the day."

From his vantage point behind so many jazz leaders, Harland has observed how fame can be a blessing to some while others waste it.

"I like the way Branford Marsalis said it," Harland describes, "when he told me when you're chosen to be the item of success, it doesn't matter what you do—'they' want you to be out there and you're going to be out there. How great you become depends on yourself—many people are great but they still sound like shit.

"But there are ones that really took their greatness seriously; they were like, 'Wow, I have this great opportunity to be in front of people' and maybe they just wanted to feel like they deserve their greatness," Harland adds. "Some people just feel like they're great; they don't know shit; they just feel like they're great— 'I'm great, notice my greatness ... thank you.' And that's good—they have a certain kind of confidence in their individualism, which is something a lot of people don't have. There are some people who are complete geniuses and they get noticed for their greatness."

"But if you want to know some shit, that's a personal journey," Harland said.

Kurt Rosenwinkel Standards Trio, Reflections (Wommusic, 2009)

Joel Weiskopf/John Patitucci, Devoted to You (Criss Cross, 2009)

Dave Holland Sextet, Pass It On (Emarcy/PGD, 2008)

Charles Lloyd Quartet, Rabo de Nube (ECM, 2008)

Joshua Redman, Back East (Nonesuch, 2007)

SFJAZZ Collective, SFJAZZ Collective (Nonesuch, 2005)

Charles Lloyd, Jumping the Creek (ECM, 2005)

Kenny Garrett, Standard of Language (Warner Bros., 2003)

McCoy Tyner, Land of Giants (Telarc, 2003)

Terence Blanchard, Let's Get Lost: The Music of Jimmy McHugh (Sony Classical, 2001)

Aaron Goldberg, Unfolding (J Curve, 2001)

Photo credits

Page 1: Courtesy of Eric Harland

Page 2: Courtesy of Healdsburg Jazz Festival

Page 3: Courtesy of Jazz Festival Goettingen

Page 4: Hilde Schmidt

Page 5: Cees Van De Ven

Featured Story: Jos J. Knaepen

Tags

Eric Harland

Interview

John Patten

United States

Charles Lloyd Quartet

Dave Holland

jason moran

wynton marsalis

Kendrick Scott

Greg Tardy

Aaron Goldberg

Terence Blanchard

Kenny Garrett

Greg Osby

McCoy Tyner

Joshua Redman

Stefon Harris

SFJAZZ Collective

charles lloyd

Zakir Hussain

John Coltrane

Taylor Eigsti

Julian Lage

pat metheny

Stan Getz

Brian Blade

Jack DeJohnette

Dennis Chambers

Tony Williams

Elvin Jones

Branford Marsalis

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Eric Harland Concerts

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.