Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Jazz

Jazz

Jazz

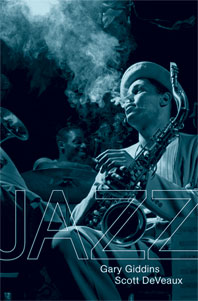

Jazz Gary Giddins, Scott DeVeaux

Hardcover; 704 pages

ISBN: 978-0-393-06861-0

W.W.Norton

2009

The only thing harder than playing jazz is writing about it. It is a music that is specific, yet hard to define. It is easy to understand, yet at times hard to comprehend, sometimes in the same song. And it is continuously old and new. In its roughly 100 year history, few books have attempted to capture the culture and complexity of the music. Marshall Winslow Stearns's The Story of Jazz, Mark Gridley's Jazz Styles: History and Analysis, Amiri Baraka's Blues People, Paul Berliner's Thinking in Jazz, and Albert Murray's immortal Stomping the Blues are among the few that are perched on that high and rarely reached literary plateau.

That plateau will have to make room for the addition of Jazz by Gary Giddins and Scott DeVeaux, two of America's most distinguished writers on the subject. Arguably, this is the most comprehensive and compelling work on jazz to date. Simply put, what Giddins, formerly with the Village Voice and JazzTimes, and DeVeaux, a musicologist who taught jazz history at the University of Virginia, and author of The Birth of Bebop: A Social and Musical History, have done is produce an eloquent and informative, multi-disciplinary work. It explains the roots and methods of the music, identifies its major and minor figures, and situates the art form in a historical socio-cultural trajectory, from its percussive pre-history in West Africa to modern times.

Comprising 19 chapters, 78 listening guides, a glossary, videography and bibliography—plus the legendary photos of Herman Leonard—the book divides the music into four phases: 1890s - 1920 (genesis), 1920s - 1950s ( from communal music to art), 1950s - 1970s (the modern era) and the fourth stage, 1970s - 2000s (the classical age). The authors strive not to "treat jazz in a vacuum, perpetuating itself as a baton passed from genius to genius (but) rather as a mix of broader, cultural, political, social, and economic factors, and attempt to line up the crucial moments in its progress with historical events that it reflected and influenced."

Even more important than tracing the well-known arc of the music's development through its New Orleans origins, Chicago infancy, Kansas City adolescence and New York adulthood is how Giddins and DeVeaux interweave the extra-musical forces into the mix. The Caribbean tinges that seasoned the music in New Orleans, where the forced marriage of mixed race creoles and blacks provided the final push that birthed the genre; how, to borrow Kenneth Burke's phrase, "antagonistic cooperation" between blacks and whites shows no signs of dissipating soon; and how jazz simultaneously manages to be a classical, popular and folk art. The authors also examine the role of the critic, and do so without falling prey to the factional madness that clouds some jazz writing today.

Of course, Giddins and DeVeaux profile the giants. Trumpeter Louis Armstrong, the promethean man-god who emerged from the ghetto and become the music's first major instrumentalist and jazz singer; pianist Duke Ellington, the Washington DC-born dandy whose thousands of compositions form the music's sonic scriptures; saxophonist Charlie Parker, pianist Thelonious Monk and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, the holy trinity of bebop; trumpeter Miles Davis, the "Prince of Darkness," who illuminated the genre with his many stylistic reincarnations; and pianist John Lewis, the erudite African-New Mexican, whose blues-and-Bach synthesis co-created The Modern Jazz Quartet. But picking up where Ken Burns left off, the writers bring 2009's young stars to the fore, specifically Houston's jazz, hip-hop and art music wunderkind, pianist Jason Moran (dig how the authors break down Moran's take on Afrika Bambaata's "Planet Rock").

Jazz shows the music as it is, in all of its splendid inventions and dimensions, at the start of the new century. It may be down as far as its presence in the media and the recording industry is concerned, but it has conquered academia, as evidenced by practically obligatory jazz programs in high schools and universities around the world. And in the end, its future is in youthful hands. "Jazz in the twenty-first century may seem no longer rife with the kind of innovators of earlier eras," Giddins and DeVeaux write, "yet it has unquestionably produced one of the best equipped musical generations ever, which has sustained jazz as a singular, stirring, and still surprising art."

< Previous

Vijay Iyer: Into The Mainstream

Next >

Something Sentimental

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.