Home » Jazz Articles » Profile » The Late Great Phil Seamen

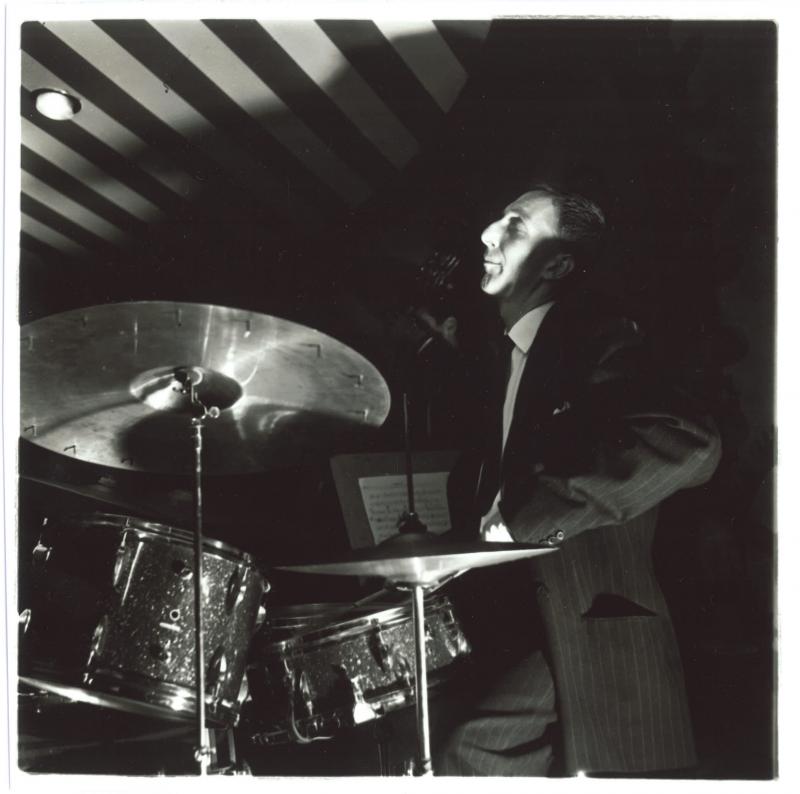

The Late Great Phil Seamen

Phillip William Seamen was born in Burton-on-Trent, Staffordshire, on August 28th 1926 and died on Friday 13th October 1972—he fell asleep in a chair in his abode on Old Paradise Street in Lambeth, south London, and didn't wake up any more. The police were called in quite quickly and their pathologist began by taking a sample of Phil's blood, which is usual procedure. Back in the lab he could not believe his eyes—the level of barbiturates was so high that medically speaking Phil should not have been alive at all prior to his death! This was no overdose, but a build-up over the years. The guy had some kind of superhuman stamina and it's true, there is the odd exceptional junkie who somehow can handle amounts that kill everybody else - and god knows he was one of them. But it finally all caught up with him, aged 46. His ashes were spread in Golders Green Crematorium remembrance garden, northwest London. Phil Seamen is arguably the greatest jazz drummer Europe has ever produced. But let's not confine his talent to 'jazz' or Europe—he was a great drummer, period.

Phillip William Seamen was born in Burton-on-Trent, Staffordshire, on August 28th 1926 and died on Friday 13th October 1972—he fell asleep in a chair in his abode on Old Paradise Street in Lambeth, south London, and didn't wake up any more. The police were called in quite quickly and their pathologist began by taking a sample of Phil's blood, which is usual procedure. Back in the lab he could not believe his eyes—the level of barbiturates was so high that medically speaking Phil should not have been alive at all prior to his death! This was no overdose, but a build-up over the years. The guy had some kind of superhuman stamina and it's true, there is the odd exceptional junkie who somehow can handle amounts that kill everybody else - and god knows he was one of them. But it finally all caught up with him, aged 46. His ashes were spread in Golders Green Crematorium remembrance garden, northwest London. Phil Seamen is arguably the greatest jazz drummer Europe has ever produced. But let's not confine his talent to 'jazz' or Europe—he was a great drummer, period.Seamen took to drugs like a duck to water. The French have an accurate word for that—toxicomane—meaning having a talent for addiction. He was a born raver. He consumed the drugs and they then consumed him; that's how it goes with junk. All washed down with copious amounts of alcohol. It's a wonder he lasted so long. But Seamen had a sharp wit and great sense of humour, which he also unsparingly applied to himself, and which must have helped him cope, along with his love for music and unfailing desire to play. As a young man he was physically big, with a chest and everything, but by the late 50s he was just a head, hands and feet, hooked on heroin. Still, he was such a good drummer and sight-reader, he was continually in demand, also being the king of the recording sessions—everyone wanted him. But getting into the 1960s, he became more and more unreliable and lost most of the recording work (he complained about magnets under his bed, which prevented him from getting up!). Whereas he had been a jazz star and acclaimed drummer throughout the 50s, as the 60s progressed his heroin addiction caused him big problems and there were periods when he had sunk pretty low. On top of that, jazz in England was ousted by the rise of pop, soul, rock music and the general onslaught of Aquarius. These were some hard and disillusioning years for the jazz scene, work became marginalised to certain pubs—plus the one and only Ronnie Scott Club—none of which paid 'particularly well.'

SETTING THE STANDARD IN THE 50s

Seamen started playing drums at the age of six. Grew up in the jazz and dance big band era. Turned professional at the age of 18 by joining Nat Gonella and his Georgians in 1944. About this move and how he came to be such a good reader, Seamen explained: "Nat was a marvel. He was a father to me—he looked after me, you know. Ten days before I joined the business, I went out and bought a drum tutor to learn how to read. Nat used to make me stay behind after the band rehearsals to practice my parts. If I made a mistake I got a clip round the earhole—sharp and swift, because Nat wouldn't stand for it. We used to get Tommy Dorsey arrangements, which had the Buddy Rich drum solos written out. And believe you me, if you've ever seen a Buddy Rich drum solo, it looks like flyshit—and that's not very nice at all!" Seamen also mentioned that he had Britian's first bebop combo together with members of the Gonella band (alto saxophonist Johnny Rogers, tenor saxophonist Kenny Graham and bassist Lennie Bush amongst others), and that Nat did not consider it music. Joined the powerhouse Tommy Sampson Orchestra in 1948, and by 1949 bop had become a real factor: Seamen and tenor saxophonist Danny Moss formed a bebop quintet from within the ranks which was even featured on a radio broadcast by the orchestra in September of '49. He then went on to play in the Joe Loss Orchestra for about 14 months, the most popular dance band of the time. Then the top job with Jack Parnell from 1951 until midway '54, from 12 to 17-piece band. Seamen was much sought after during the 50s, he set the standard—also playing in Kenny Graham's Afro-Cubists projects from 1952-58, from 1954 onwards with the Joe Harriott Quartet, the Ronnie Scott Orchestra and Sextet, and an ever extending list including Dizzy Reece, Victor Feldman, Jimmy Deuchar, Kenny Baker, Don Rendell, Stan Tracey, Tubby Hayes, Laurie Johnson, as well as blues stars Big Bill Broonzy and Josh White, countless sessions.

He married the beautiful young West End dancer Leonie in 1956, whom he had met while with Parnell, working together in the show 'Jazz Wagon.' His hobby was fishing. And in 1957, on February 8th to be exact, Seamen was finally on his way to America, about to fulfill a lifelong dream—to hear all the greats live, play with as many icons as possible, hang out with the best drummers. The Ronnie Scott Sextet were going over on the Queen Mary to do a tour as part of a Musicians Union exchange deal. But going through customs in Southampton prior to boarding, Her Majesty's custom officiers took one look at him, pulled him aside and Seamen got busted for possession of drugs. In spite of a solemn agreement with his fellow musicians, having stashed the marjuhana in the seat of his drumstool and enough heroin for the voyage in other secret places in his drumkit, he just completely goofed it by having one shot in his coat pocket! Slung in jail until his case came up, then released after being fined 80 pounds by the magistrate, Seamen never made it to the States. (Ronnie Scott ended up having to fly Allan Ganley over for the tour, and never really forgave Phil). He was terribly disappointed. But he picked himself up. In 1958 the West End production of West Side Story opened with Seamen—Leonard Bernstein reputedly specifically asked for him and, despite the heroin and alcohol, the producers hired him and he was magnificent.

SURVIVING THE 60s

In 1960 Joe Harriott came with his 'free form' concept and new quintet: no more chord changes, a lot of interplay rather than one soloist after another, searching for collectiveness—a great group. Seamen saw it as his job to keep things swinging, and that he did. In my opinion his playing in this group was his absolute artistic highpoint. Across the board, Phil's popularity was rising and, combined with a 'certain notoriety,' he was the man: he could work drum magic in any setting, a figure who was larger than life itself, often causing uproar, sometimes not turning up at all. But his wife divorced him in '61, after five years of marriage to a junkie she wanted a normal life! He was devastated, but for any addict, not finding the next fix is the most devastating thing imaginable. Later on in '61 he bought a lovely German Shepherd pup and the two of them became inseparable.

During the first half of the 60s he worked a lot with Tubby Hayes—including a famous 'sit-in' by Dizzy Gillespie when they were playing at Ronnie Scott's in November '61—and Joe Harriott, in '62 played a couple of nights with Dexter Gordon at Ronnie's (Dexter: "Every night there was a new drummer—but Seamen was great!"), recorded with Carmen McRae, in '64 played r&b with Alexis Korner, Georgie Fame. Started teaching in 1962 and one of his pupils was Ginger Baker, who went on to influence a whole generation of rock drummers. However, heroin really was getting the better of him, his health was deteriorating, and increasingly many bandleaders would not hire him any more. So Seamen did work at Ronnie Scott's—with British bands, but it is a grave misconception that he was ever 'the house drummer.' Whereas Stan Tracey was 'the house pianist' from 1960-67, Ronnie would not book Seamen to back the visiting Americans because he was 'so fucked-up and a tad unreliable,' and one must remember these were 3-week stints. Notable exceptions were with Freddie Hubbard in '64 and Roland Kirk in '67 (followed by a UK tour).

From 1965-66 his regular gig was with the Dick Morrissey Quartet, also worked with the Harry South Big Band, in '67 with Stan Tracey, Joe Harriott. Studied tympani at the Royal School of Music briefly with Sir James Blades: "Phil was so enthusiastic to begin with, but increasingly didn't show up. It was the drugs, you know. It was so sad. He was a percussion genius." Then Philly-Joe Jones turned up in town. Another longtime heroine addict, he came to live in London from 1968-69 as a registered junkie and was unable to work due to stringent Musicians Union rules. Things became ridiculous during this time, with Phil and Philly-Joe having drug-consumption competitions, with an array of powders, pills and potions all stalled out, to see who would slide under the table first. Worked the pubs with pianist Tony Lee. Then, after the break-up of Cream and the short-lived Blind Faith, Ginger Baker formed his own group Air Force, initially for just two concerts, and asked Phil to join. Phil agreed, Ginger was honoured. They began rehearsing in December '69, the premiere was at the Royal Albert Hall on January 17th 1970. Seamen did a bunch of gigs with Air Force—in Birmingham, Denmark, France, the Lyceum in London, and in Holland, but by May found the music too shallow. "Too bloody loud!" was his comment. But this taste of super-stardom and standing ovations by thousands of youngsters seemed to jolt Seamen into some kind of new found self-respect. He became the toast of the jazz-pub circuit. Formed a quartet with Derek Humble in '70, but Derek died in January '71. Regular work in the Brian Lemon Trio, played with Tony Coe, Tubby Hayes. In May 1972 the co-operative group Splinters, an initiative by Stan Tracey, played their first gig. An all-star improvising group, the object was to bring together musicians with different backgrounds: Tubby Hayes, Trevor Watts, Kenny Wheeler, Tracey, Jeff Clyne, John Stevens and Seamen. Phil had always been wary of 'free jazz' but here, as he had done in Joe Harriott's freeform quintet, he played 'time.' The beginnings of Splinters were promising and who is to say what might have been—Phil passed away in October.

PHIL THE DRUMMER

So weaned on big band swing and dance music—including the quickstep, foxtrot, waltz et al—Phil got bitten by the bebop bug. This was a musical revolution and he embraced it immediately, as the 'new music' gradually arrived by way of vinyl records. He was one of the vanguard group in Europe to do so. He was knocked out by Kenny Clarke's liberation of the drum set and the new role the drum set was given by Kenny, Art Blakey and Max Roach: this suited his personality, without a doubt coincided with his own belief in 'emancipated' drums, and inspired him to invent his own version. It was well-known by the jazz in-crowd that Dizzy Gillespie had had Chano Pozo in his band, but in London there was the 'real thing' straight from West Africa, centered around Nigerian Ambrose Oladipupo Campbell. Ambrose had been around since 1945, and Phil was a big fan: Ambrose could play both the modern palmwine music and traditional Yoruba rhythms. In 1952 his group the West African Rhythm Brothers found a permanent showcase as residents in the Abalabi club on Berwick Street, a magnet for a cross-section of humanity including regulars such as Kenny Graham, Ronnie Scott, Sir George Bernard Shaw, and Phil Seamen. Phil loved the layered and melodic approach in African drumming and, again, invented an own version on drum set, incorporating it into his already existing style and thereby enrichening his whole approach. He listened to drummers from Africa whenever possible. Kenny Graham and he also fanatically analysed and notated Cuban and Caribbean music. The point being that while Art Blakey started researching Afro rhythms during the 50s in New York, Phil Seamen had been doing the same in London, possibly even starting some years earlier. Phil's drum style was his own sparkling mix of the three elements of big band swing, bebop and Africa.

When the small boy Phil Seamen picked up sticks and started drumming away, he employed the 'matched grip'—as any normal kid would. The 'orthodox grip' is an unnatural way to hold two sticks, a remnant of marching music, retained by jazz drummers after the birth of 'the drum set,' seated down in some New Orleans brothel parlour. There is nothing technically to be gained by using the orthodox grip—on the contrary. However, the whole jazz style of playing had been evolved by using the orthodox grip, and so a certain re-invention was required, particularly playing brushes with its crossing over etc. Phil stuck to his initial intuitive matched grip, thereby going right against the prevailing 'official' view: he was told he held his sticks incorrectly, but he paid no attention to that—a rebel from the outset! But using the matched grip was a major contributing factor to how he sounded different: for example he was able to do things over his toms, across and back and forth, because his single-stroke playing was so developed—and generally speaking one's hands are more equal because they perform the same movement. Phil was the only one who played exclusively with that grip, so that in itself makes him an innovator. It seems fair to say that Phil Seamen personally was responsible to a large degree that the matched grip replaced the orthodox grip in Britian. There have been some great rolls in jazz drumming, such as by Jo Jones, Buddy Rich, Cozy Cole, Art Blakey, but Phil Seamen truly had a really nice roll too.

You could fault Seamen for being somewhat of a conservative. He never got into the Elvin Jones thing of opening up the beat, preferring to keep his hihat going, he didn't like Tony Williams' playing, he saw playing 'free jazz' as treason, he kept on using a 24 inch bass drum. But he remained true unto his convictions—and you can't fault a man for that. He had fanatically fought for 'the beat' in the not so beat-conscious European music climate from the moment he hit the scene, having to 'row the Queen Mary through a sea of mars-bars,' as he put it, on many an occasion. He set the standard of 'swing' in Britian, and many a great American musician was flabbergasted by his innate ability. Where did he come from, who are his forebears? Phil Seamen was a spirit.

SOME COLLEAGUES AND QUOTES

Louis Bellson: "The first time I went over to England I heard Jack Parnell's band, and he had Phil Seamen playing drums with him and he was a terrific player. Boy, he could really swing, and do all the things that he had to do. There was an example of a guy that took care of business in a big band. That was really a thrill, to watch and hear Phil play."

In 1958 Phil visited Paris and went to hear Kenny Clarke at Le Chat Qui Peche. Phil's presence was noticed and Klook invited him to sit in. He remarked to Phil afterwards: "You're the first man on drums I've heard swing since I've been here!" (He had moved to Paris in 1956). Kenny remained a big admirer of Phil ever since that first meeting.

Philly-Joe Jones: "Yeah, Phil and I were friends when I lived in London—we used to hang out together. There were other drummers, like Tony Kinsey and Oxley, you know, they all have their way of playing, but Phil was about the best."

Bassist Kenny Napper: "At his best he was a wonderful drummer, and he had a really fast wit—he was a formidable personality, he was in awe of nobody. One time in a police station, brought in for disorderliness, he was asked to walk the white line and answered: Sure, bring it over here!"

Ginger Baker: "There were few drummers in the world who could come close to Phil Seamen. He was the most wonderful drummer you ever heard. He came to hear me at the Flamingo, I think it was in 1960, I was unaware that he was there till I got off the stage to be confronted by God! And I went back to his flat and we spent all night listening to his African records. For me, Phil's knowledge was like opening the door and letting the sunshine in. Without Phil Seamen I would never have been the drummer I was."

Composer Laurie Johnson: "I used a lot of jazz players in my orchestra. Phil Seamen was always there. He might stand around the whole afternoon [in the recording studio] just to hit a gong. Yet no one could do it quite like Phil. He was an exceptional musician, much more than a drummer."

Bassist Dave Green: "It was always so exciting playing with Phil—you never knew what he would do next! He had the best bassdrum sound I ever heard, sounding like Big Sid Catlett and Max Roach at the same time."

< Previous

A Night In Sana'a

Next >

The Kandinsky Effect

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.