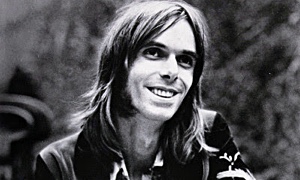

Home » Jazz Articles » Film Review » Clint Eastwood Presents Johnny Mercer: The Dream's On Me

Clint Eastwood Presents Johnny Mercer: The Dream's On Me

Johnny Mercer

Johnny Mercer Clint Eastwood Presents Johnny Mercer: The Dream's On Me

TCM

2009

Film director Clint Eastwood's love of jazz and American popular song is far from a secret, especially following his feature-length biopic about alto saxophonist Charlie Parker (Bird, 1988), during which the ever restless Eastwood got the idea to produce a feature-length film about pianist Thelonious Monk, released somewhat later during the same year as Straight No Chaser. Hence, it should surprise few that Eastwood will introduce viewers to a month-long 100th birthday celebration of American lyricist Johnny Mercer on Turner Classic Movies (TCM), beginning with Eastwood Presents Johnny Mercer: The Dream's On Me, which will be telecast in the U.S. on Wednesday, November 4, 2009 with a repeat on Wednesday, November 18. Throughout the month of November, when Mercer would have been 100, Wednesdays on TCM will be devoted to classic Hollywood films with lyrics penned and, in some instances, performed by Mercer, who not only wrote but sang more hit songs than virtually any other American songwriter.

The Eastwood opener is admittedly a "teaser," a mosaic of familiar songs and faces that nevertheless succeeds in giving viewers, regardless of their degree of familiarity with Mercer, plenty of motivation to delve into his considerable body of work. (The Complete Lyrics of Johnny Mercer, published by Knopf earlier in 2009, must surely rank among the thickest, heaviest tomes ever produced.) While Mercer's is a familiar voice and face to anyone who remembers the popular music of the 1930s and 1940s, as well as his later work with singers Bobby Darin, Andy Williams and Barry Manilow (who set his elegiac lyric "When October Goes" to music before releasing a recorded performance posthumously), it comes as a surprise to even many of his steadfast admirers to learn that it was Mercer who founded Capitol records, which would go on to become one of the several most important recording companies of the latter half of the 20th century.

But above all, Mercer was a man of words. And more than that he possessed an ear for the vernacular that was capable of transforming song lyrics into poetry. Of all the talking heads in the movie, no one speaks words more from the heart than Tony Bennett: "As far as I'm concerned, Johnny Mercer is American literature." Unlike the sophisticated and cosmopolitan Cole Porter or the ironical, complex Lorenz Hart, Mercer was a regional writer, practically cut out of the same cloth as Southern authors like William Faulkner, Flannery O'Connor, Eudora Welty, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, Harper Lee and James Dickey, his subjects as much about the sights and sounds of nature as the many faces of romantic love. Bing Crosby is heard stating that Mercer was thought of in the business as the "Huck Finn of American popular music" and as a "good ol' Southern boy."

But the key to Johnny Mercer's art was, more than all else, his love of Southern black culture. Born into a wealthy family, he waived college in favor of exploring the black neighborhoods of his native Savannah, combing stores for the "race records" of the time, and at one point receiving a citation from a black organization that had never met him personally as "our favorite colored singer." Although the Eastwood film attempts to distribute the influences more evenly, pointing out that early on he discovered the witty word play of W. S. Gilbert, the attentive listener or reader of Mercer's lyrics is soon apt to nod in agreement with the words of writer Wilfrid Sheed: "For all his adaptability, there was a black-jazz base in everything Mercer wrote" (The House That George Built, Random House, 2007).

As mentioned above, the clips of Mercer, including his appearances with trumpeter Louis Armstrong and singer/pianists Nat King Cole and, above all, Ray Charles, (Mercer practically changes character when it's his turn to join the duet), are all very brief. Rarely is a song featured for more than eight measures before it fades into the background, yielding to the narration of pianist Bill Charlap or another clip. But the cumulative effect of so many short clips featuring Mercer himself leaves a lasting, memorable impression, practically daring the viewer not to look more deeply into the life and work of one of the century's indisputable geniuses where the dovetailing of music and words is concerned.

Apart from the brevity of the musical clips, the film does have its share of obvious, no doubt unavoidable, flaws and omissions. It barely touches on Mercer's "demons"—the alcoholism that seems to have haunted the majority of America's great writers—and once again it is the least likely of the film's guests who makes any mention of it, the habitually sanguine Tony Bennett. The torrid but hopeless love affair between Mercer and Judy Garland is briefly looked into, though the role of Mercer's wife, Ginger, is handled as gently as possible. And no doubt some viewers will question the choice, apparently made by Eastwood, to give a number such as the title song as well as the ever-popular "Moon River" to an amateur singer, in this case his own teenage daughter. A cynical interpretation is that Eastwood was viewing the project as an opportunity to show off his daughter, but there's another, far more charitable and commendable motive.

Although Mercer can provoke anyone writing about him to cite verses that compare favorably with the poetry of the great Romantics—Wordsworth and Coleridge, Shelley and Keats—this is not the reason that, of all American lyricists, he is the only one to have inspired artists—first Ella Fitzgerald, then Susannah McCorkle, Rosemary Clooney and Nancy LaMott, among others—to devote entire albums exclusively to songs with words by Mercer. His singular appeal, no doubt, can be found in the sentiments of a tribute read at a public occasion by Fred Astaire on July 22, 1976, barely a month after the lyricist's death: "Johnny maintained that unique quality that is the essence of genius—a common touch he expressed in uncommon lyricism." That's the quality that Eastwood wanted to capture in this film, and that's the human being he wanted us to see—a genius we could all claim as one of our own.

Production Notes: 217 minutes. Two discs. Executive-producer: Clint Eastwood. Produced and directed by Bruce Ricker. Narrator: Bill Charlap. Extras: Interviews with Clint Eastwood, John Williams, Andre Previn, Julie Andrews, Bing Crosby, Michael Feinstein, Jack Lemmon, Audrey Hepburn, Gene Lees, Alan Bergman, Leonard Maltin, Robert Kimball, Miles Kreuger, Blake Edwards, John Dankworth, Cleo Laine. Clips from films and musical shows, ranging from Old Man Rhythm (1935) to Li'l Abner (1959) to Days of Wine and Roses (1962).

Tracks: (song fragments): Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive; Trav'Lin' Light; That Old Black Magic; Midnight Sun; Somethin's Gotta Give; I Had Myself a True Love; I Wanna Be Around; My Shining Hour; Blues In the Night; Laura; Spring, Spring, Spring; I'm Old Fashioned; Any Place I Hang My Hat is Home; This Time the Dream's On Me; Dream; I Thought About You; Two of a Kind; Skylark.

Personnel: Larry Goldings: piano and organ; Kyle Eastwood: bass; Michael Feinstein: piano and vocal; Tony Bennett: vocal; Nat King Cole: piano and vocal; Louis Armstrong: trumpet and voice; Jack Teagarden: trombone and vocal; Ray Charles: piano and vocal: Ella Fitzgerald: vocal; Bono: vocal; Jamie Cullum: piano and vocal; Dr. John: piano and vocal; Hoagy Carmichael: vocal; Bing Crosby: vocal; Johnny Mathis: vocal; Andy Williams: vocal; Mel Torme: vocal; Dinah Shore: vocal; Judy Garland: vocal; Rosemary Clooney: vocal; Margaret Whiting: vocal; Frank Sinatra: vocal; Lena Horne: vocal; Mary Martin: vocal; Maude Maggart: vocal; Morgan Eastwood: vocals; Johnny Mercer: vocals.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.