Home » Jazz Articles » Music and the Creative Spirit » Greg Osby: A Candid Conversation

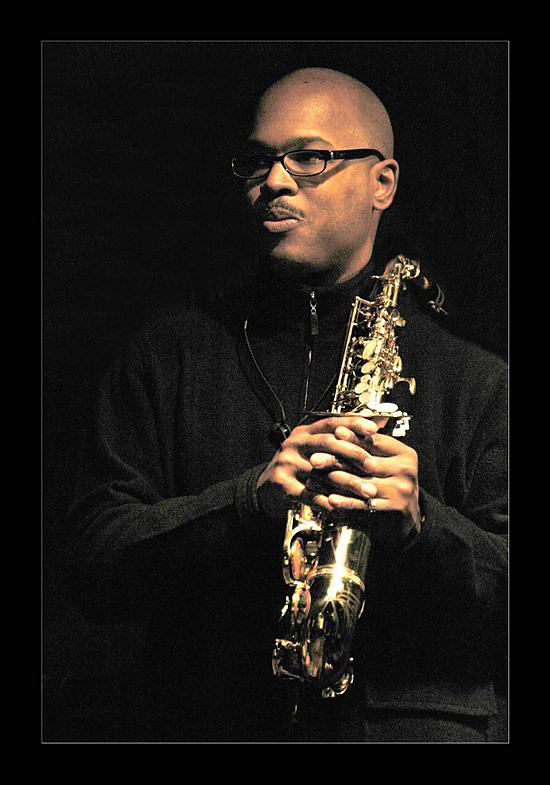

Greg Osby: A Candid Conversation

I have found that with forward-thinking artists, their music can be a direct reflection of who they are. That's largely my interest in these very creative individuals—in how they think and how they view the world through their own eyes. Greg Osby is fearless in expressing his convictions, and I think you'll find that his compositions reflect that very character. He is a creator and a fresh voice in a world that has a tendency to fall victim to the past.

I have found that with forward-thinking artists, their music can be a direct reflection of who they are. That's largely my interest in these very creative individuals—in how they think and how they view the world through their own eyes. Greg Osby is fearless in expressing his convictions, and I think you'll find that his compositions reflect that very character. He is a creator and a fresh voice in a world that has a tendency to fall victim to the past. Lloyd Peterson: Are you still doing things your own way?

Greg Osby: I have no other way, and creatively speaking, I customize my career so I'm able to make choices without interruptions. And though I'm a collaborator at heart, I still need to adhere to my initial ideas and concepts.

LP: It would be difficult to meet everyone's expectations anyway.

GO: You just can't please everyone or beat yourself up trying to please writers who may have written unfavorably about you in the past or by trying to pander to the tastes of label executives and fans. As an artist, you want to sleep at night knowing what went into the stew was an ingredient of your own design. I don't want to sound self-indulgent, but it's not about pandering to what people want or about what's popular because you can box yourself in based upon those expectations and parameters. I would rather let the music write itself based upon the initial germs of thought and maintain that focus. Otherwise, you'll get off track worrying about awards and accolades.

LP: Are jazz traditionalists having a difficult time accepting that a music form considered "American" now has more visible international and diverse aspects within it?

GO: The problem is overkill. The floodgates are open with an overabundance of substandard product because everyone has access to some kind of recording medium, whether they are ready to present a project meant for public consumption or not. So in order for people to get to the real gemstones, they have to sit through the muck. They have to get a machete and hack through the jungle of CDs that are not really developed and print quality. They haven't played long enough or shared any experience that would give them music to market of permanency. Most of it is disposable, but you can still find accomplished musicians everywhere you go. Everywhere I go, whether it's Germany, Russia, Spain, Italy, Brazil, Australia or whatever, I find great musicians who are often on par with American musicians, who in many respects have gotten lazy and taken for granted the demands of this art form. You have a lot of prominent musicians wrestling with the laurels and not realizing that there are people in New Zealand who can blow their socks off. The music was originated here, but it doesn't mean it cannot be perfected somewhere else.

LP: Are the roots of jazz from Africa?

GO: Yes, but as an art form, jazz is the epitome of fusion. Of course, it has West African root elements with functional drumming as well as a great deal of symbolism, but it also emerged heavily with Western European sensibilities as far as harmony. So a lot of the rhythm, the feel, the soul, the swing, is African, but a lot of the structural elements are largely European. That's what made the music what it is. Those are the things that need to be referred to and relied upon to fortify and strengthen it, but many people are just maintaining the precedent as it stands without being concerned with moving it to the next level. But we need to take heed and follow the lead of John Coltrane, Charles Mingus, and Miles Davis and continue to press forward and not idealize the music as some type of museum piece frozen in time. It should be perpetual.

LP: Is jazz a thing, or an approach and process to making music?

GO: It's all of the above, but it's also a mentality and a way of life. It can be readily apparent if the music doesn't contain the stylistic characteristics of a jazz musician living a jazz life. You can tell when the music is largely academic or from a book or from records. You can tell they are not professionals that don't travel because they don't think with that aptitude. It's obvious, and especially now when there are 100,000 tenor players copying the flavor of the day. You should have individual personalities, and everyone should sound different as you and I sound different in our vocal patterns, mannerisms and our complete character profile. The lack of individualism and motivity toward assuming and maintaining a personal approach and a personality in the music is killing a large part of what this music is supposed to be about. When someone plays, it should evoke imagery of someone who is like no other.

LP: But are the academic programs placing enough emphasis on the importance of this?

GO: I'm a veteran of the institutionalized approach to jazz education from teaching at many well-known universities, and I have been at odds with their methodology in approaching music. I think it should be individualized based upon the aptitude and aspirations of each student, as opposed to this broad stroke and grand sweep of everybody given the same information and forced to adhere to the same list of requirements. There isn't any reason why someone in music school should be forced to study and be held responsible for anything not having to do with the jazz life. There should be more emphasis on business, self-promotion and the attainment of individualism that will make you stand out and make you more appealing to label executives; they throw away thousands of audition CDs daily that sound like they came out of a Xerox machine.

GO: I'm a veteran of the institutionalized approach to jazz education from teaching at many well-known universities, and I have been at odds with their methodology in approaching music. I think it should be individualized based upon the aptitude and aspirations of each student, as opposed to this broad stroke and grand sweep of everybody given the same information and forced to adhere to the same list of requirements. There isn't any reason why someone in music school should be forced to study and be held responsible for anything not having to do with the jazz life. There should be more emphasis on business, self-promotion and the attainment of individualism that will make you stand out and make you more appealing to label executives; they throw away thousands of audition CDs daily that sound like they came out of a Xerox machine.

LP: There are now younger musicians that don't necessarily want to be tied to what jazz did in the past, though they have a tremendous respect for those that came before them. These musicians are trying to move in different directions while finding their own identity and voice.

GO: There is a danger of being dismissive of a precedent or the lineage of the music. Many people are reckless because they don't want to do the work, but in order to get away from something, you have to be aware of it. You have to know how it worked, how it was applied and what it derived from. You have to know the root source, otherwise it's escapism, and people are just trying to circumvent deep study. So there is a danger in that cavalier attitude of "wanting to do my own thing." That's why we have a great deal of people who are not really well versed in the history of this music. They play their own music and play it fairly well, but put them in another environment and they sink like a rock because they don't know anyone else's music and have given its due.

LP: Miles Davis was criticized for incorporating pop influences into his music, but jazz has always taken from pop influences. Is there anything different in what Miles was doing or what is being done today by a number of jazz musicians?

GO: Well, in the '30s, '40s and '50s, there was less divide between the genres because many jazz musicians during that period openly improvised within the confines of the forms of those popular tunes, which had a great deal of chord changes, bridges and development. As time progressed, especially in the 1960s when rock and roll came around, popular music was reduced to one or two chords with a lot of screaming, hollering and a lot of guitar. There was less of an environment for musicians to improvise with, and now with electronics, it's gotten worse! That has hurt the scene at large because a lot of people at one time were introduced to jazz through an instrumental version of a popular song they may have recognized. But you can't do that today. I cannot introduce the uninitiated to jazz by playing a pop tune of the day because the songs from Britney Spears and *NSYNC have only two repetitive chords, have no development without anything for me to play on. That's why jazz has been relegated as this bastard child within contemporary music. It doesn't contain any appealing elements that are recognizable to and by young people. So until popular music becomes interesting again, we can't play that music, and it's going to remain difficult to reel people in.

LP: Does hip-hop have elements from the foundation of jazz?

GO: At one time, but now it's become disposable and pretty much a waste of record deals, in my opinion, because most of these people are idiots. It's become a circus. In many instances, it's buffoonery at its finest with very little profundity being uttered. Hip-hop may have been different at one time, but there was a lot more creativity in the production and construction of the music. It was more or less a cut-and-paste music where they sampled little snippets of recordings that didn't resemble or have anything to do with each other. It was a collage of sound textures that created an environment and pallet for rappers who artfully and rhythmically created rhymes, short stories and poems. But once the sampling walls became more strident and artists went after these rappers for sampling their wares, there were exorbitant lawsuits. Now it's been reduced to two notes on a keyboard with children's nursery rhymes. It's not interesting anymore, and all they talk about is money, so it's really disposable.

LP: Can you talk about M Base Collective and the basis for starting it?

GO: I found it necessary to seek out a group of younger players, players in my peer group that were interested in incorporating elements from music that existed prior to our arrival in New York as well as music that existed at the time. I also found many improvising musicians dismissive of what was going on in contemporary terms, so I wanted to use everything that existed as a building block, as a steppingstone, and not stay transfixed in a rapt state or try to create a bygone era.

There was also this vast influx of younger players from all over the country who came to New York well prepared, proficient, articulate and ready to learn. This was the beginning of what was unfortunately called the "young lions period." We were also the last beneficiaries of the apprenticeship system and had the grand opportunity to play with our heroes. But after us, a lot of people passed on and stopped having groups, so we became the bandleaders younger players started to look toward. But we wanted it organized.

I met fellow saxophonist Steve Coleman and found we had a great deal in common and a great deal of aspiration to revitalize the scene and not just make it this young lions thing. We didn't want to reinforce that. Even though we did play traditional music, we also wanted something that was reflective of what was going on now. We wanted an experimental environment where we could write new music and talk about new concepts, new approaches and implement things that were of our own concoction. Once we were organized, we met once or twice a week in our basements or apartments and talked about music. It was really a self-propellant entity, where if one of the members had a meeting with a music executive, an attorney or had a session in the studio, we would address the group and detail our experiences. Consequently, we all lived vicariously through each other's experiences, and when we had to confront those experiences on our own, we were well prepared. We also pooled our money, and paid for our own studio time, and put on our own concerts as well as starting an outreach program for student teaching with a musicians' referral service. And through these efforts, a lot of the journalistic elite took note and started to call us 12th and Brooklyn, but we wanted to nip that in the bud.

I met fellow saxophonist Steve Coleman and found we had a great deal in common and a great deal of aspiration to revitalize the scene and not just make it this young lions thing. We didn't want to reinforce that. Even though we did play traditional music, we also wanted something that was reflective of what was going on now. We wanted an experimental environment where we could write new music and talk about new concepts, new approaches and implement things that were of our own concoction. Once we were organized, we met once or twice a week in our basements or apartments and talked about music. It was really a self-propellant entity, where if one of the members had a meeting with a music executive, an attorney or had a session in the studio, we would address the group and detail our experiences. Consequently, we all lived vicariously through each other's experiences, and when we had to confront those experiences on our own, we were well prepared. We also pooled our money, and paid for our own studio time, and put on our own concerts as well as starting an outreach program for student teaching with a musicians' referral service. And through these efforts, a lot of the journalistic elite took note and started to call us 12th and Brooklyn, but we wanted to nip that in the bud.

Whenever you think of harmolodics, you invariably think of Ornette Coleman because that's what he named his music. But we didn't want anyone to coin a phrase as something as ridiculous as bebop, which is a phrase that musicians abhorred. So we decided to call our music M-BASE; that is an acronym that stands for "Macro—Basic Array of Structured Extemporization." Roughly meaning a large base, a large group of musicians whose main purpose is to learn and teach each other and to present new methods of composition and environments for improvisation.

GO: It's a new day as far as being a practicing musician and trying to sustain an existence. You have to choose between playing an instrument and playing in creative circles. You can play for money where there is not a great deal of creativity, but you're a faceless, nameless commodity who is doing what they are told and is basically a hired gun. Or you can make less money and sleep better at night by expressing yourself based upon your creative ideals.

I advise younger players to prepare and to avail yourself of the information—free information, mind you—about everybody's job who is involved in this business. You have to be able to speak with them articulately about what you are dealing with at the moment. You need to be able to talk to recording engineers, attorneys and music executives. You will need to know how the record company and contract works—how promotion, marketing and distribution work. Around the '40s or '50s, you went around with a dog collar and people pointed you in the direction you needed to go. That's why a lot of musicians were shafted and died penniless because they didn't have their business together. They were gypped out of all their money by lawyers, managers and record company executives who took all of their royalties, their spoils, and now today, you have to know everybody's job to know they're not doing that to you.

LP: One of the problems with documentation of jazz, such as the Ken Burns' series, is that they spend most of the time concentrating on what jazz created in the past tense and little on what the music is creating at the moment, which to me is the essence of this great music we call jazz. Isn't this a lost opportunity to educate potential aspiring jazz students and people as to what is available to them?

GO: Well, perhaps if he would have had a more variable list of advisers, but it was obvious who his advisers were because they're all friends of mine. I know how they think, what they prioritize, and that was reflected in the documentary. They spent several episodes talking about Louis Armstrong and several more talking about Duke Ellington, so whose philosophy does that reflect? Had Ken Burns had a more variable list of advisers, the film would have been a lot broader and much more comprehensive. Perhaps they ran out of budget when they came to the more recent period, or maybe they ran out of steam—ran out of ideas—or maybe everybody got cotton mouth and became tired of talking. The point is, it was unfortunate that he stopped when he did. He was in fast-forward from the late '50s and '60s with some of the most profound contributors to the music of American culture, and if you blinked, you would have missed it. And that was just unfortunate. They spent so much time in the mid-1900s as opposed to dealing with what's leading up to now.

Another aspect that was really disappointing is that he talked about the dark side of the most profound contributors to the music. He talked about their drug addictions and alcohol addictions, which is really nonessential. It took up time where he could have provided worthwhile, useful and retainable information. That stuff was disposable more or less.

LP: There are already so many negative stereotypes, why not focus on the positive?

GO: The thing about documentaries, especially something like this, which was mass-produced, is that they will be referenced in academic circles. There's no point in all that. If you look at the movie Amadeus (1984), it was readily apparent that they considered Mozart a child prodigy, a genius who changed music and had these God-given gifts. He was amazing. Even for all his quirkiness and eccentricities, the things he did were astounding. He had inner demons, was haunted by his father and died a pauper. Still, the symphonies and the concertos that he composed as a young person were portrayed with love. But when you see movies like 'Round Midnight(1986) and Bird (1988), they always portray the jazz musician as down on his luck, depraved, dependent upon some golden goose who has rescued him from the depths of hell. They can't take care of themselves; they're groveling, drooling somewhere in the shadows. The lighting is grim, dark and gray. In many respects, the Ken Burns documentary perpetuated that.

LP: Throughout all the arts, there have been many well-known and creative people with highly addictive personalities, yet it does seem that many jazz or black artists usually get portrayed in this negative light. It continues to occur.

GO: It's just history repeating itself. People will glamorize the things that provide drama, and it's tabloid mentality. It's voyeurism for people who want to peek into the dark side of freakish behavior, sexual deviancy, drug addiction, alcoholism, the dark secrets and sordid past. The documentary could have spent a good deal of time talking about the innovation, experimentation and great achievements by musicians and could have been a lot more effective than it was.

LP: If Miles would have been alive, would he had been included as a resource?

GO: It's possible, but I'd like to touch upon something you said earlier. He was criticized, but by the time he was doing Michael Jackson and Cindy Lauper covers, he had nothing left to prove. He was having a lot of fun and surrounded himself with musicians that I won't say didn't deserve to share the stage with him, but they weren't really on his level. They just provided a sonic backdrop for him to be a personality and not Miles Davis the musician that he once was. He was having fun and wasn't out to change the whole face or the tide of music. Subsequently, he wasn't this vortex of energy that he once was, and it shouldn't have been expected of him. And people unfortunately and selfishly attacked him for that. A lot of musicians attacked him for that, but that's their shortcoming and not his.

LP: Though Miles wasn't playing a lot during this later period, he could still play one note and you knew it was him.

GO: Certainly. It was his sound, his personality, his approach, his attack and his technique. Everything was definable and unmistakable, and that's what it's all about. He could have played one note per tune, and it would have been just as valid had he played 100. And that's something that takes musicians a lifetime to achieve, and some people never attain that because that's not a point of emphasis or focus. They want to display technique, velocity, volume and all the other kind of things that are not necessarily priorities or the prerequisite to identification.

LP: Our culture today appreciates art but seems to have difficulty with creativity that is not easily explained or identifiable. Will this be a significant obstacle to overcome for creative music?

GO: Well, I think the conditioning that takes place for understanding has to be dealt with at a very young age. It's very common for us musicians to see entire families coming out to see us in Europe. They come out to see pure bona fide American jazz that's not cut or watered down and recognize it as a valid and credible United States export. They cultivate this thinking in the minds of the young people, so when they grow up, they appreciate it as something to be embraced, to be treasured and virtued. And that's what we need to deal with in this country because most people identify the music as my grandfather's music or something heard in cartoons or in the backdrop for a slapstick comedy, silent films or something ridiculous. That's the association and imagery it conjures up when they hear jazz. The only thing that serves as a bridge for younger people and jazz is probably hip-hop, and they just hear it in snippets. They may hear a sampled fragment from a jazz recording, but they can't identify the source of the artist, or where it's from or what period it represents. It's throwaway. It goes in one ear and out the other, and they really don't retain that information.

And unfortunately, the most prevailing so-called jazz presentation right now is this so-called "smooth jazz," which really isn't jazz at all. And the people that are popular within that whole structure, they're really not jazz musicians. They're pop musicians, and what they play is pop music. If you take the vocalist out of any pop song or Mariah Carey song, what you have is this so called smooth jazz. It's the same environment, the same sugar coating, the same instruments, and it has the same disposable nature. Even the improvised elements are very much prepared. They play the same way all of the time, and it adheres to a formula, which isn't about individuality. Jazz now has to find a way to shake the association of being under the same umbrella and grand veil of so-called smooth jazz—instrumental jazz. You have to learn how to appreciate the elements, the relationships, know the history, how things work and the lineage of it to develop an appreciation for it. It's not an easy sell.

And unfortunately, the most prevailing so-called jazz presentation right now is this so-called "smooth jazz," which really isn't jazz at all. And the people that are popular within that whole structure, they're really not jazz musicians. They're pop musicians, and what they play is pop music. If you take the vocalist out of any pop song or Mariah Carey song, what you have is this so called smooth jazz. It's the same environment, the same sugar coating, the same instruments, and it has the same disposable nature. Even the improvised elements are very much prepared. They play the same way all of the time, and it adheres to a formula, which isn't about individuality. Jazz now has to find a way to shake the association of being under the same umbrella and grand veil of so-called smooth jazz—instrumental jazz. You have to learn how to appreciate the elements, the relationships, know the history, how things work and the lineage of it to develop an appreciation for it. It's not an easy sell.

LP: Do you think we have become a society that no longer has the patience to be challenged and is only open to things that are easily accessible?

GO: Americans in particular—perhaps not so much in Europe because they don't have the same access to a lot of things that we do. I find that people from other countries read more, but yes, Americans have short attention spans, since we're victimized by the multimedia-ness of contemporary culture with emphasis on what is visual and not necessarily what's heard. Yeah, we're suffering. But all things are cyclical, and these things have to run their course. They have to because how many pretty girls and belly buttons can you stand?

LP: Is it more difficult for young musicians to be creative today?

GO: When I came to New York in 1980 or so, and then officially moved to New York in late 1982, there were tons of jam sessions. In every major borough—Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx and certainly Manhattan, with the exception of Staten Island—there were jam sessions. You could go on a daily basis and see who was hot and who wasn't. We listened to the new musicians in town to see if they were ready to compete or if they needed a few more months to hone their talent. You could weigh your skill level against the more accomplished players and find out exactly what your weak points were and what you needed to work on. But all of that is gone. There are only a few places for a younger player, and you have musicians lining up out the door to get in and have their 15 minutes of fame. And by the fact that there are not many places to play, these musicians get up and overstay their welcome. They're frustrated, so they get there and play a long time, and by the time the night is over, most have not had an opportunity to play. So I don't know what to tell a young cat to do. They ask me, "Where should I go?" and I don't know. There are only a couple of places to play, and there are too many musicians; therefore, they only get a chance to play in school, but that's not the same thing because they are only playing with people on their own level. One guy is sad, and so they are all sad, and it's hard to weigh yourself against a group of sadness.

LP: Cecil Taylor said, "Music has a lot to do with a lot of areas which are magical rather than logical; the great artists, rather than just getting involved with discipline, get to understand love and allow the love to take shape." How much of your music is from love, and how much from this other place that Cecil Taylor describes?

GO: There's a great deal of fundamental logic in just about everything I embark upon in music because I cannot and will not allow myself to recklessly enter into a situation or environment without deducing what needs to be done. I have to analyze the situation and weigh my various approaches, compounds and needs in order to make a successful contribution. Jumping in headfirst is like jumping into a pool without assessing the depth of the water. This is very important to me, and I have my own opinions about players who just recklessly charge in with guns a-blazing, playing real loud and fast without taste or character—without regard to tone or without trying to fit into what everyone else is doing. It's like some loud drummers who don't care about the ensemble, but only about bringing attention to themselves, or even piano players that just because they have 10 fingers, want to make sure they use them all. They're whole presentation is like a run-on sentence without punctuation. They don't breathe or stop because they don't have to, and I like to avoid that kind of recklessness.

LP: If the perfect situation is complete freedom, shouldn't this creative process have intent? Isn't there responsibility, with its own set of disciplines that comes with that freedom?

GO: Freedom of expression is the result of knowing what choices to make. If you don't know what choices to make through study and acknowledgment of history and making yourself aware of the environment you're in, then how are you to know the decisions you are making are going to be sound? Many people have and are dismissive of the precedents that have been established within the music. It's like running out into traffic with a blindfold on. You have to know. You have to have your sensibilities honed, and you have to know the game. You have to know the laws in order to break them, to alter them or to modify them.

LP: Are you aware of where your inspiration or creativity comes from?

GO: That's a very interesting question, but I would have to contend that there are certain biological characteristics that are inherent in people from different ethnic origins and backgrounds. It's self-evident when you see children of one ethnic group embrace certain characteristics in music or they find a beat or a rhythm. They latch onto certain melodic circumstances, and some people just don't. People can argue that, but it's self-evident. I don't want to say that means someone is dominant, but some people are predisposed to certain tendencies, and that's just the way it is. But I don't want to generalize because that's like saying all Asians are computer whizzes and all Indians are predisposed to being doctors. It's quite ridiculous, but there is an abundance of aptitudes, such as young black children that can dance as soon as they can walk. They can find the beat or the rhythm. That's almost racist in and of itself in saying that all black children are predisposed to be entertainers or basketball players.

LP: Can you connect music politically, spiritually or socially?

GO: I try not to be detached from what's going on, but outwardly, I'm not making any bold political statements because the politics that I abide by are my own politics. I don't abide by the politics of a 60-plus-year-old, silver-haired white guy in Congress. We don't share the same aptitude, the same aspirations, nor are we born of the same environment. There isn't any way that they can see my world or have any empathy for it. So the politics and ideals that I'm presenting in my music are based upon a historical precedent of personal philosophies of self-preservation, motivation and a progressive, reckless, relentless curious spirit. That also includes continued growth and prosperity through development and continued learning, and that's what it should be about and not about taking arts programs out of schools to provide money for national defense or close libraries so that we can manufacture more biological synthetic viruses. They have their agenda, and I have mine.

LP: What have you learned about yourself from all the risks you have taken?

GO: It sounds cliched, but you cannot please everyone. However, I try not to be self-indulgent or an artist saying, "Yeah, I'm playing for myself, and the hell with the audience." A lot of people do, but they remain poor. I'm not in it for the money, either, but genuinely to produce work and to share it with people who are interested. I'm not interested in appeasing people who turn a blind ear to the music or people who have it in for me and will never like it. I'm not trying to convince them. I'm trying to convince people who are into new ideas, new approaches, and convince them there are other ways that possibly may inspire them to see yet another option or to take another path, whatever that discipline may be, and it may not even be music. There are ways to assume and maintain variables in whatever you do, and hopefully, I'm an example for that, and I may be inspirational to some degree. I'm hyped about these things and really excited about it. I just like to share and hopefully draw in people who are interested.

LP: What is it about jazz and the art form that is important to you?

GO: That you can't hide behind it, and you're either proficient or you're not. It's like these older jazz cats after listening to younger players, "Ah, he ain't playin' nothin.'" They're all gruff and grimy, and all the technique in the world cannot save you if the statements that you make are not reflective of experience or serious aptitude toward that which you are trying to talk about. Perhaps the best analogy would be the guys recently released from prison. When up for parole, they voraciously read a lot of books for three months in the penitentiary library, and then come out on the street trying to talk like they read War and Peace (1869) while using bad syntax. Killing sentences dramatically and functionally, which is like musicians who try to act grandiose in their portrayal of romanticism in the profundity of the jazz life, and they are 18 years old—or they may be 30 years old, but they still don't have a story to tell. They can only tell a tall tale because they hide behind technique and bravado, but you can't hide behind a smokescreen in jazz. Unlike other music where people are swayed or distracted by dancing girls, pyrotechnics and the big stage show—it's more of a spectacle—jazz is stripped bare with four or five guys on stage and it's as honest as you can get. Either you have it, or you don't, and either you're doing it, or you're not.

LP: Do you have a vision for jazz and for yourself personally?

GO: I see a healthy future because players are becoming more proficient at an earlier age. The transition from sad to proficient is a lot shorter because of the abundance of intellectual means that are available. It's a good thing. Now we just need an environment for them to hone those skills, so that they can see what works and what doesn't. People in my peer group need to actively look to the younger players, so that we can nurture and school them and point them in the right direction. I received it from Dizzy Gillespie, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, McCoy Tyner, Muhal Richard Abrams, Andrew Hill, Jim Hall, and on and on. I went on the road as an apprentice with these people and saw the life of the road and all the dos and don'ts. That's the only way it's going to survive. Just because they have some talent right out of college doesn't mean you can't expect them to be the golden goose or savior for your label. Invariably, they are still stepping on each others feet because they don't know what to do. And signing too early actually stunts their growth, and the really sad part is that if they don't make good on the investment, the label drops them like a hot potato, and they become damaged goods at 21. Now the only thing they can do is go slumming toward little independent labels in Europe. They are like has-beens before they are 25, and they don't grow, but stay at the same level. But if they get with someone older and experienced, they can grow progressively and become better and better.

LP: Do you have a philosophy or way of looking at life?

GO: I try the best I can to maintain a sense of innocence and curiosity and remain a student of life. It keeps me active and thinking about what's next, which is all I can do. Once I get comfortable and resolve that I know it all or believe I have made my grand statement, well, that's the kiss of death, and I have seen it happen. But you are only as good as your last profound statement or offering, and I don't want that to be the snapshot that I'm referring to for the rest of my life, frozen in time. At the conclusion of any recording session or any performance, I'm thinking about tomorrow or what I'm doing next . . . always! That's fodder for progression, and it's all I need. I don't want my band to become comfortable and start daydreaming, so I have to keep the hot coals aflame underfoot—otherwise, it's time to get new cats. I can't replace myself, so the best I can do is to stay innocent and maintain that I don't know everything.

This interview was originally published in the book Music and the Creative Spirit (The Scarecrow Press, 2006).

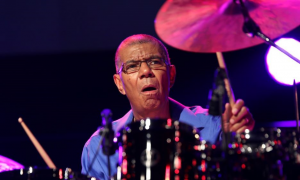

Photo Credit

Page 4 by C. Andrew Hovan

Page 6 by Kay-Christian Heine

All others courtesy Greg Osby

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.