Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Charli Persip

Charli Persip

I like to solo, but I like it to be rhythmic and musical. So many drum solos end up being demonstrations of technique...

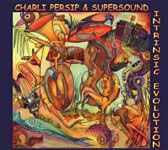

People looking for the magic elixir, the Fountain of Youth, should stop looking and start jazz drumming. Charli Persip, who'll turn 80 in July, will soon join Roy Haynes and Chico Hamilton as fully active octogenarian jazz drummers with busy careers. Persip grew up in Newark, NJ and, after touring with Dizzy Gillespie's small group and State Department Big Band (1953-58), he became one of the most in demand drummers on jazz recordings, especially big band ones, in the late '50s and early '60s. He's continued to work steadily ever since and has been leading his big band for a quarter-century. Charli Persip's Supersound's new album is Intrinsic Evolution and they play an exclusive engagement this month at York College.

People looking for the magic elixir, the Fountain of Youth, should stop looking and start jazz drumming. Charli Persip, who'll turn 80 in July, will soon join Roy Haynes and Chico Hamilton as fully active octogenarian jazz drummers with busy careers. Persip grew up in Newark, NJ and, after touring with Dizzy Gillespie's small group and State Department Big Band (1953-58), he became one of the most in demand drummers on jazz recordings, especially big band ones, in the late '50s and early '60s. He's continued to work steadily ever since and has been leading his big band for a quarter-century. Charli Persip's Supersound's new album is Intrinsic Evolution and they play an exclusive engagement this month at York College.All About Jazz: The book you wrote on drumming has an odd title: How Not to Play Drums: Not for Drummers Only. How did that title come about?

Charlie Persip: The irony is the title came from Dizzy. When I got in his band I knew all the arrangements, I loved that band, and I thought I played my ass off. Dizzy pulled me aside and said "You seem to know the arrangements pretty well and be doing a great job but now that you know what to play you gotta learn what not to play". And the subtitle, Not for Drummers Only, is because the book is all about the instrument; not just how to play, but how to take care of your body, exercise. It's a book for everybody with any interest in drums. And I have my patented drum exercises you can do by just patting you hands and tapping your feet, you don't have to have a drum set or be a drummer to do them, and they'll help with your coordination.

AAJ: I saw you with that Dizzy big band that had just come off a State Department tour at a Carnegie Hall concert in 1958. That was the beginning of a very active period of recording for you. You're the drummer on one of my favorite big band albums from that time, Bill Potts's The Jazz Soul of Porgy and Bess. What do you remember about that date?

CP: That was a heckuva album. I had an incident on that record date that really propelled my reputation and gave me a lot of good publicity out of doing something bad. It was scheduled for three dates at Webster Hall in Manhattan, each from 9 a.m. to noon. United Artists didn't want to go over budget so it was to be four tunes per date. On the first day we only did three tunes. The second day was a Tuesday and I had played Monday night at Birdland and overslept; got to the record date at 10:30. Everybody hated me. As soon as I walked into the date the musical director said "Take One". I just walked in and sat down and since the band had already rehearsed without me we just hit it. And we did five tunes that day. He never thought that he would ever congratulate somebody for being late, but he said that was one of the greatest exhibitions of sight reading he'd ever seen. And because of that and some dates I'd done with Johnny Richards Orchestra at Birdland, my stock really went up because of my reading ability. So I made a lot of money, but it didn't really do a lot for my artistic benefit. Buddy Rich recommended me for Harry James's band behind my work on that Potts album. Buddy was always very good to me.

AAJ: How did you get to be such a good reader?

CP: Mainly because I objected to the word that was going around that jazz drummers couldn't read well. Then it translated into black drummers couldn't read well. I totally took umbrage to that. I said OK I'm gonna be the best reader in the land—I'll fix you. I spent many hours practicing, I took music books to bed with me to read instead of novels. I was fighting the fight for the good name of black jazz drummers.

AAJ: You learned some of that in school, right?

A. No, actually I never studied any instrument when I was in school. I was self-taught. Learned mostly the parade stuff first. When I got to school I really wanted to play football. Went to West Side High School (in Newark) because Arts High didn't have a team. The West Side football team wasn't any good and neither was I. In my junior year I joined the marching band and that was a lot of fun because I'd never played in any kind of band before. I used to go see the big bands at theaters; the Adams Theatre was my real university when it came to how to play big band drums. That and listening to a lot of records my older sister had. During my last year at West Side the music department formed a stage band and I tried out for it and made it. That was the first time I found myself in a big band situation and that did it for me, I made up my mind there and then that I was going to be a professional drummer.

AAJ: So you went to Julliard.

CP: That was later. Once I got out of high school I was playing around Newark, there were still a lot of little bands around town. I studied with a private teacher, Al Jamanski, who got me to improve my technique and put me on the road to reading. Then I played the R&B chitlin' circuit up until the early '50s then joined Dizzy right after that and that was my first chance to play bebop. Wade Legge was the pianist and baritone saxophonist Sahib Shihab was in that quintet too. Everybody is dead except me. It's kinda sad you know. One of the reasons why I don't like to spend a whole lot of time talking about what I used to do is because so many of the people I worked with are gone. And the young kids they want to know about and see something and it's hard to get through to them when you talk about people who are gone they can never see.

I like to talk about what I'm doing now and plan to do in the future. But I will say one thing though, about the time I spent with Billy Eckstine as his personal drummer. People think of big band when they think of him, but I was in grammar school when he had a big band. I was with him when he had a small group, mostly a trio. I joined him in 1966. Surprisingly enough all the bands I'd played with, Dizzy, etc., I got closer to a personal style of playing with him than with any of those other bands. Part of it was there was no influence—with all those other bands there was at least a mild influence of other drummers who had worked with them before. I had my own voice but it was greatly influenced by the other drummers. When I joined Billy there was no prior influence of a drummer (they hadn't traveled with one before) and (pianist) Bobby Tucker and I got together so that I could play with the same kind of imagination I would play with with a big band, but so as not to get in Billy's way. That was what really made that gig interesting; I mean I stayed with him for seven years. We did big bands, trio and had a small band book as well. And I was able to play with the same abandon, so to speak, that I would do with an instrumental band. What helped me do that was I really began to perfect the art of listening. That is so important, as you know. And it's easier said than done.

AAJ: I see you also worked with one of my favorite musicians and people, Randy Weston?

CP: Oh yeah, Randy was great. When I recorded with Randy it was the first time I got to play something in three (3/4 time), "Little Niles". After I got to play on that album, Elvin Jones—we were very good friends, Elvin and me—was getting ready to record "My Favorite Things" with John Coltrane and he asked me "How do you play in three, I don't know what the fuck to play?" I was so shocked; as good a drummer as he was I was flattered and shocked and everything and the rest is history. If you hear "My Favorite Things" and you know he learned how to do it. Another band I was very pleased and flattered to have been with is Gil Evans. That was the other band I played with that helped me learn about listening and broadening my concept. I went with Gil Evans after Billy Eckstine. Gil always said that there were two drummers he liked to play in his bands, Elvin and myself.

CP: Oh yeah, Randy was great. When I recorded with Randy it was the first time I got to play something in three (3/4 time), "Little Niles". After I got to play on that album, Elvin Jones—we were very good friends, Elvin and me—was getting ready to record "My Favorite Things" with John Coltrane and he asked me "How do you play in three, I don't know what the fuck to play?" I was so shocked; as good a drummer as he was I was flattered and shocked and everything and the rest is history. If you hear "My Favorite Things" and you know he learned how to do it. Another band I was very pleased and flattered to have been with is Gil Evans. That was the other band I played with that helped me learn about listening and broadening my concept. I went with Gil Evans after Billy Eckstine. Gil always said that there were two drummers he liked to play in his bands, Elvin and myself.

AAJ: Lets talk about your band; you've been doing the Superband since the 1970s, right?

CP: I call it Supersound now because of the Phillip Morris Superband. I was advised not to sue/fight them even though I had the name first because you're going up against serious money and a company like that can just keep postponing things so my wife, god rest her soul, said change the name to Supersound. Started out as trumpeter Gerry La Furn's rehearsal band in the late 1970s, and I became the drummer in 1979. The idea was to make it the resident band at Manhattan Plaza, but things didn't work out and when Gerry wanted to keep the band together he asked me, since I had the bigger name at the time, to be the leader. So the first album we made was as co-leaders. Right after that Gerry got upset with me because he wanted things I didn't want and as a leader I vetoed them. I don't mean that in a negative way. I don't like to brag, but I have become somewhat of a master of programming, I know how to program really well. I learned from bands how to do it. I would program and Gerry would complain. He liked to sneak in low energy and build up, I like to kick off strong. I took the band over and made some personnel changes and Frank Foster gave me seven arrangements, then fired me from his Loud Minority band because he felt I should have my own band. That's how the band got started and we did our first album in 1985.

AAJ: What was your goal, your musical goal, with the band?

CP: To play music starting from the bebop era and into whatever the music is now and hopefully something into the future. You hear the band now you'll hear a little bit of fusion, you'll hear Afro-Latin, you'll hear a whole lot of bebop of course. Thats really the musical direction of the band. Another reason I wanted to keep the band together, and I don't mean to be racist or anything, was because here's a band led by a man of color so other musicians of color can aspire to. Most big bands are led by white people and then they have basically white people in their bands. I had a really great talk once about this with Mel Lewis—we were really good friends—we talked about that whole situation and he said if you're a white band leader you know more white musicians than musicians of color.

AAJ: But your band seems to be pretty integrated.

CP: And that's what I wanted. At one time I was thinking of naming the band just Culture. I like diversity. I don't want it all people of color, I don't want it all white, I don't want it all Asian, I don't want it all women, I don't want it all men. I want a little bit of everything.

AAJ: Where did you find all these musicians in the current band?

CP: They find me. Every musician who is in this band today called me. I never called anybody. Maybe when someone left I did, but that's rare since usually when they left the band they would recommend somebody. They really seem to love me and I love them. You can feel a really great great spiritual feeling in the band, and that's what I want. We've all heard about the tyrannical bandleaders, the liars and the cheaters who've held up the money, we've all been through that. So one of the my goals was that everyone was going to be very comfortable and very happy to be in the band. And they know they can trust me as far as the money is concerned and that's what's kept the band together.

AAJ: On the new album I see band members have contributed quite a few of the charts.

CP: That's the other thing. As the band grows we're being more self-contained as more members are bringing music into the band. The last arrangement we brought into book numbers 136.

AAJ: What is your input as to how the charts are developed?

AAJ: What is your input as to how the charts are developed?

CP: I let the composer write the way they want. Then when they bring it in to the band I may reshape it to some degree, without hurting the composer's ideas. That way the band can have some kind of identity.

AAJ: What about who solos? I was pleased to hear so many trombone solos; big bands don't feature them enough, in my opinion.

CP: I let them set the solos, and oh yeah, James Zeller got up one day and said "We don't have enough solos in the trombone section". That's the kind of band we have, man, it's both a democracy and a dictatorship. There are times I have to be a dictator, but the dictator doesn't have to be a tyrant.

AAJ: I also notice you don't take that many drum solos, especially for a leader-drummer.

CP: No I don't want to do that. I want to play with the band, I want to be on the team. It's like a football team. You have to have a lot of stars, a running back and a tight end and wide receivers and a blocking back and they all handle the ball. I like to have a lot of soloists. I don't wanna solo on every tune. To me a lot of drum solos get boring after a while. I want it to be music. I went through that you know, the period of the long drum solo, but I passed that, I kinda don't like that anymore. All due respect to the great drummers who are still playing great solos today but I don't want to do that, I want to try to make music. I like to solo, but I like it to be rhythmic and musical. So many drum solos end up being demonstrations of technique—you know, how fast you can play and blah blah blah.

AAJ: One of the pieces on the new album, Joe Henderson's "Punjab," is arranged by another drummer, Joe Chambers.

CP: He brought it to me for the band and asked if he could play it, but I said no this is my band. He meant well, probably wanted to show me how it should go, but that's the last thing I want. I never want to hear another drummer play something that I'm going to play because then that's going to be in my ear. I'm trying to find my own voice when I perform, especially in my band. Gary Anderson out in California, who also was never in the band, wrote another one on the new album, "Meantime," which was supposed to be our venture into fusion. It hinted at fusion. I like fusion, want to play more fusion, don't get a chance to play it enough, like it a lot.

AAJ: It also has some bop elements in it.

CP: Oh yeah, it's not complete fusion. What I'm trying to do in the band is to have a hint of different musical genres without actually being them. It's like the Latin things we do, it's kind of my way, not necessarily the way a Latin band would play it. I'm always trying to find my own voice.

Recommended Listening:

Dizzy Gillespie, At Newport (Verve, 1957)

Charles Persip, And the Jazz Statesmen (Bethlehem, 1960)

Pat Martino, Baiyina (The Clear Evidence) (Prestige-OJC, 1968)

Charli Persip & Superband, No Dummies Allowed (Soul Note, 1987)

Randy Weston/Melba Liston, Volcano Blues (Gitanes/Antilles—Verve, 1993)

Charli Persip & Supersound, Intrinsic Evolution (s/r, 2007)

< Previous

Shakti

Next >

Working On A Dream

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.