Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Steve Swallow: The Poetry Of Music

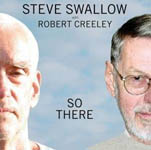

Steve Swallow: The Poetry Of Music

[Creeley's] words contained all that [music], and it was just a question of extracting what was in there already.

Bassist Steve Swallow and poet Robert Creeley were friends for 30 years. Swallow first read Creeley's work in the 1950s, and instantly fell in love with what Creeley had to say and the way he said it. Twenty years later, a chance meeting with Creeley led to a personal and professional relationship. Creeley's work inspired two of Swallow's albums—Home (ECM, 1980) and his most recent recording, So There (XtraWATT/ECM, 2006).

Bassist Steve Swallow and poet Robert Creeley were friends for 30 years. Swallow first read Creeley's work in the 1950s, and instantly fell in love with what Creeley had to say and the way he said it. Twenty years later, a chance meeting with Creeley led to a personal and professional relationship. Creeley's work inspired two of Swallow's albums—Home (ECM, 1980) and his most recent recording, So There (XtraWATT/ECM, 2006).AAJ contributor Jason Crane talked with Swallow about So There and his relationship with Creeley. Swallow proved himself to be as consummate an appreciator of poetry and life as he is a master of the electric bass.

All About Jazz: What made Robert Creeley's work stand out when you first started reading it in the 1950's?

Steve Swallow: I'd say it was the same qualities that I most admire to this day. His concision, his extraordinary sense of rhythm, and what he was talking about seemed in a kind of uncanny way to be speaking directly to me. I discovered him in the mid-'50s, I would guess, and had the sense that he was addressing me personally then, and held on to that through it all. As I got to know him as a person, I felt that we did indeed share some perspectives on how life worked.

AAJ: Can you give an example?

SS: I became an avid collector of what he wrote immediately starting in the mid-'50s, and I have a pretty complete library of what he's written. I thought to make the album Home with [vocalist] Sheila Jordan. I began working on it in the early '70s and didn't record it until '79 or maybe '80. I went through everything he'd written very deliberately, with an eye or an ear for what I thought could be sung well—purely the poems that seemed to have lines to me that evoked music. I put bookmarks in all the appropriate places and then typed out all that I got. Then I looked it over and realized that all the poems I'd chosen were ones about love, the romantic ones. And that's by no means predominant in his poetry. I'd say, in fact, that it's a small piece of his whole pie.

AAJ: Was that a function of choosing things to be sung and romantic lines are a fairly common topic for lyrics?

SS: It wasn't that I was choosing the words for their meaning at all. I was really just choosing sounds and rhythms. I didn't care what the text was initially. I remember being very clear with myself about that—that I needed syllables that formed well in the mouth, and vowel sounds that produced the best vocal sound, and the rhythms that seemed conducive to musical phrasing. I wasn't looking at content. I was unaware of content as I did that in that initial gleaning for Home. I already had Sheila Jordan in mind and was thinking of her voice. Her voice had always been a very personal matter for me. She'd moved me deeply when I'd played with her over the years.

So it wasn't until stage two of the process, when I'd sat down with what I'd chosen and typed it out, that I realized that they were all love poems. I remarked on that and didn't pay it much mind. I went ahead and set the poems I liked best, and in the course of seven or eight years produced the music that would become that album.

I made that album in late '79 or early '80, and I think a week or two after it was recorded my wife split and I was devastated. As you can imagine, it was one of those big life or death events. We'd been together for quite a while and had kids. In the course of floundering around in the aftermath, I went back and listened to the album and looked at the poems that I'd selected but hadn't used, and found tremendous solace or consolation there. Several years prior to the event, [it turned out] I'd chosen a text to read to myself to get over the feeling of devastation that I was experiencing. I consider that a remarkable and quirky experience.

In fact, I was in touch with Bob. We've had a long correspondence that started in the early 70's and continued until a week or so before he died.

AAJ: You lived near each other at one point, right?

AAJ: You lived near each other at one point, right?SS: Yeah, in the early '70s. Again, entirely by coincidence. It's a remarkable thread of coincidence and magic that's run through our relationship. In 1970 I moved to northern California, north of San Francisco, a bohemian enclave called Bolinas. A wonderful town on the very tip of San Francisco Bay. It wasn't until I'd actually settled there with my family that I discovered that Bob lived there. We'd corresponded, but I'd never noticed the postmarks. At that time, we got to know each other considerably better and the idea to work with his poetry took form in my mind. His daughter babysat my kids. We had a day-to-day life together—a day-to-day life near each other—as neighbors, which helped because I was so thoroughly in awe of him up to that point. I guess I never really lost that, but as I got to know him better I was able to loosen up and speak in his presence.

You can imagine how incredibly difficult it was to write to him. His letters, which had that kind of tossed-off quality that his poetry has—and he does try to toss it, I think that was his modus operandi, to achieve that rhythm you get when you just sail along as the words pile up in your mouth and you exit them as rapidly as you can. On the other hand, I would just ponder over my little three-paragraph responses to his letters for days trying to get the language right, to try to meet the standard that was implicit in everything he said. If he was talking about going to the store, there was an extraordinary song in it.

AAJ: I can imagine writing letters to a world-renowned poet must be like showing your score to a famous composer or giving your demo tape to your favorite musician.

SS: Exactly. So it was an incredibly fortunate coincidence that I was able to get to know him and just sit around and talk about the lengthening nights in November and the day-to-day stuff of living, which is a lot of what his poetry is about. To see that the line between everything one addresses in the course of a normal day and that thing you call poetry is really an illusion. That's one of his lines that I've always loved: "Is that a real poem or did you just make it up?" I think somebody said that to him at one point. I love what's implicit in that.

I got lessons from him at every turn. There's an obvious lesson for me to learn about bass playing, which is not to take it too seriously. To approach bass playing, in a sense, in the same way you approach going to the store or eating your toast in the morning.

AAJ: When you first wrote to him, was it simply as a fan of his poetry, or had the idea of using his poetry as a springboard for music already come into your head? When did you first write to him?

SS: I guess the initial letters came after I knew him in Bolinas in 1970 or '71. When I left Bolinas, we just kept in touch, and the idea that I was going to work with his poems had already arisen when we were neighbors. So we were discussing that from the outset. In fact, to go back, there was the extraordinary event of finding that the poetry of his I'd chosen was just what I needed to get over the dissolution of my marriage.

We were writing back and forth at that time, and he also very soundly and very matter-of-factly told me, "Don't worry about it, you'll find a better one. I did." And this addressed that whole immense issue of the wrenching life change that the dissolution of a relationship cause, in terms that made it seem as simple as putting a letter in an envelope and addressing it, or whatever else you do in the course of a day. The amazing thing is that my sense is that the way in which he leveled things for me didn't diminish anything. It had the opposite effect—it made all the events in a day more important and portentous and significant in ways that you had to dig deeply to apprehend. I think that's a lesson that poetry in general can teach.

AAJ: How did Robert Creeley respond to the first record, Home?

SS: He loved it, which was immensely gratifying to me and also a great relief. He loved Sheila's singing. He had been and remained until his death one of the great jazz listeners of all time. He told me early in our relationship that he had written a lot of his early stuff listening to tapes of [pianist] Bud Powell. He liked to reminisce about hearing [saxophonist Charlie] Bird [Parker] at the Hi-Hat Club in Boston when he was going to school in the late '40s. So he was hearing Bird at his peak. He had relationships with several musicians. He and [soprano saxophonist] Steve Lacy were pretty good friends, and Steve did a project using his words. He always seemed to know the guys on the scene and spent a lot of time in the clubs—I guess less as the years went on.

He was an avid listener and an acute listener. He really heard what was going on, and I think the evidence of that is in his line, the rhythms and the structures of his writing. They seem to me to be as musical as music. I think the lessons I've taken from his work inform the way I play as much as any of the lessons I took from [bassist] Percy Heath or [composer] Igor Stravinsky.

I think it's a very good idea to venture beyond your specific medium. If you're a painter you really ought to read a lot and listen to a lot of music, and if you're a musician you really ought to look at a lot of paintings and read a lot. I think the lessons embedded in the other media are often easier to use than what you steal from your fellow musicians. In the end, it's awkward to try to play exactly like [bassist] Paul Chambers. I think you're doomed to fail. But if you read a great poem and it strikes you that there's something about the structure of it that could be important to you as a music writer, you're likely to succeed in following that impulse to a successful conclusion, which would be in effect a successful piece of music. It's akin to if you want to hit the bull's-eye with your arrow, don't look. Just raise the bow and let it rip.

There's certainly value in transcribing your favorite players' solos and learning them, and in studying the musicians you most admire very carefully. I wouldn't deny that that's an important part of the process of getting good at music. But I think that what comes to you from other, non-musical sources can be equally valuable and in many cases more valuable. I found something in Bob's work that spoke directly to me in a way that no other artist of any discipline did, and it would have been foolish to ignore that. I got stuff from him in an extraordinary variety of ways. As I said, I got comfort and solace from him, but I also got technique from him, and I learned a great deal about the general issues of form and shape and elocution—the whole ball of wax.

I think he was pleased to hear that from me because of his high regard for jazz music. I once told him that I thought he was one of the best horn players I'd ever played with. We did occasional gigs together where he would just bring a bunch of his poetry and leap in and read one every now and then. The usual jazz and poetry thing. But I think he was the best at that because it was indeed like accompanying a great saxophone soloist, to leap into the words he was saying, to find something to play with him. He was thrilled to hear that I saw him as a horn soloist and [he] loved that analogy.

I think it was from that conviction that it eventually occurred to me that I ought to write some music to his speech. When I did the album in 1980 with Sheila singing the words, I deliberately violated the sense the words made when placed on the page. When Bob reads, if you're reading along with him, you'll see that the lines mean something. The length of the lines and the placement of the lines on the page. You'll see that his readings honor what's placed on the page.

I didn't do that in writing for Sheila at all. In fact, early in the process of writing that album I wrote to Bob and asked him if that was okay, that I was finding in the course of writing phrases to be sung that I'd often distort the sense that he was making on the page. He wrote back immediately like a permissive dad and said, "No problem at all. Follow your nose." So I did, but I thought that as I approached this album, So There, that there was something extraordinary in the way he delivered his poetry that I had lost, or that I hadn't exploited when I set them for somebody to sing.

So I did kind of the same process that I had done in the 1970s. I went through everything he'd written once again and I made a fresh set of choices. I know that it was 60-some-odd poems, most of them very short poems or fragments of poems, bits of longer poems. I got him to read one summer day a few years ago up here in a studio in Woodstock [NY]. Then I took those 60-some-odd poems and lived with them for some time without setting pen to manuscript paper.

And then [I] slowly began to hear. I think the first thing I needed to hear was a sense of pulse in each poem that I chose. There was by no means a common pulse that ran through each thing I'd chosen. Some of them were slow and some of them were fast and some of them were medium. Some of them seemed to be a straight-eighth-note feel and some of them seemed to be a triplet feel and they were a wildly diverse bunch of poems. I only ended up using 18 of them. There were some real beauties that didn't get done, but if I waited long enough, they all had an underlying pulse. I'd be curious if I applied these same strategies to other poets if the work would go as easily. My feeling is that Bob in particular has a strong relationship to jazz since the 1940s. The rhythms in that music and even the melodies and even, stretching the point a bit, the harmonies. And that's not so far-fetched, given that his relationship to the music has been so ongoing and so intense. If I had to pick a pair of ears to play for, they'd be his without a doubt.

At any rate, it was a very concrete process. If I waited long enough, I'd begin to find a pulse that would translate into a metronome marking. And it would be very specific. It would be "quarter note equals 132" and if you did it at 134 it wouldn't work. But there was, in each of the poems, a pulse going on. I'm sure that he wasn't counting himself off. And I would guess he wasn't doing that deliberately, but it was there.

I think somewhere in his process—in the way he made poems, probably on an unconscious level—there exists that pulse. In the course of getting started on a poem, if he's sitting there at his desk alone, wondering where an idea is going to come from and fiddling with a pencil, I think one of the first things that happened to him was likely a sense of pulse. As I said, I would guess it was unconscious, but I'm convinced that it was there because I was able to discover it in all the poems that I set and in many of the ones that I ended up not setting for one reason or another.

In any case, that was the initial step in my process. Once I'd determined the beats per minute and had the metronome ticking away as he read, it became an issue of time signature and phrase length and, even beyond that, the entire structure of the songs became clear. I readily give him entire credit for all of that, because that's what I wanted—for the poems to generate that information. I felt like a guy who's just taking dictation. After determining the pulse, I'd see that there were clear divisions of four-beat measures and five-beat measures, and it seemed to break into groupings of six beats, and then return later to groupings of four beats. So I'd write that down and jot the words down below the measures as they came out, and before I knew it I'd have a skeletal form of what the piece was.

AAJ: Where in this process did the idea of bass, piano and string quartet emerge?

SS: Quite early. Actually before I began the work. That's just how I do it. I seem to work best if I know before I begin whom I'm writing for and what instruments, what kind of sound. Previous to this album, I'd done a series of trumpet/tenor [sax] quintet albums, just because I wanted to address that very classic Horace Silver Quintet sound. I felt that was something I needed to do in the same way that my best friend Carla Bley decided at some point that she needed to confront conventional big band instrumentation. It's the elephant in the room, and you need to acknowledge its presence. So I'd done a bunch of trumpet/tenor quintet writing over a period of eight to 10 years.

Then I brought that down further to just a trio—the trio with [saxophonist] Chris Potter and [drummer] Adam Nussbaum. Again, before a note hit the page, I'd decided that that's what I wanted to do. I made that decision primarily because my work up to that point had relied on harmonic information, perhaps too much, to generate a structure and provide the soloist with a structure to use.

AAJ: That sounds like the reverse of what happened with So There, where you had a suggested structure and built the rest on top.

AAJ: That sounds like the reverse of what happened with So There, where you had a suggested structure and built the rest on top.SS: Exactly. And as an interim thing, the trio with tenor [sax], bass and drums was an attempt to come to terms with counterpoint. The absence of a chordal instrument made me confront the dynamics involved in two single-note lines interacting. After that project was done, there was a period of reflection that lasted several months. The end result of that was a decision to return to Bob's words and to elucidate further the stuff that I had learned from him over the years. I felt that since I'd done that first album, I had a better handle on what he was doing. I'd gotten better as a reader. And he'd written a lot of stuff that I thought was an advance on his part as well and I wanted to explore that stuff.

I decided at the same time to move in the opposite direction. Instead of narrowing down even further from the trio music, I decided to bite off something that I'd wanted to do for some time but had been afraid of doing, which was to write a lot of notes on the page. This led me to string quartet and to non-improvising musicians. Again, I'd been listening to that genre for years, but I really intensified my listening and bore down on Beethoven and Shostakovich and Haydn. Of course, the most I listened, the more thoroughly intimidated I became. I nearly bagged the project several times and felt that it was the height of presumption to write string quartet music.

But I kept returning to it and decided very early in the process, before any notes got written, that I wanted [pianist] Steve Kuhn to be involved. In part because he's a very good friend and a friend of long-standing. He'd become a friend of Bob's as well, and I liked that connection. Beyond that, I felt he was the right guy for the job. He'd done some projects with [composer] Gary McFarland many years before that I greatly admired. One was called October Suite (Impulse!, 1966). Gary McFarland is a vastly under-sung great jazz writer. His career was incredibly brief, and there's not enough evidence of how remarkable his ears and his skills were. Steve had done some stuff with him that ventured into that very murky grey area between improvised and written music, or jazz and classical music, whatever you want to call it. I wanted to go there and saw that Steve was ideally equipped to do that. I knew also that he had a considerable knowledge of the music and the idiom that I was, with great trepidation, approaching.

I was lucky that I had these poems to give me so much in very concrete terms—structure, phrase lengths, rhythm feels, all that kind of stuff. It's really scary to write for musicians who don't normally play together and to find the music that works to bring musicians of disparate backgrounds together. You never know until you do it whether it's going to work or not. I think I was the recipient of a certain amount of good luck, for which I'm very grateful.

Steve and I went to Oslo [Norway] and met with the Cicada Quartet. Neither of us knew them, nor did we know their work. Luckily, we all enjoyed each other's company very much and found ways to work together and to work out whatever problems arose in playing together. It was a great stroke of luck. I contacted them on the advice of Manfred Eicher, the head guy at ECM. I sifted through the people I knew who might steer me toward the right string quartet, and eventually settle on Manfred and put myself in his hands. I asked him to get me a quartet, the one he thought would be best. He took that very seriously and made me send scores. When I asked him, I was about halfway through the project, so I sent him about 30 minutes worth of string quartet writing. He took a careful look at it and suggested that quartet, and I'm very grateful to him.

AAJ: As I normally do, I listened to this album several times before reading anything about it. I was amazed to learn that there were several years between the recording of Robert Creeley's voice and the recording of the music. The seamless integration of those elements is really incredible. It struck me like taking some archival recording out of the library and writing a suite around it. How did you deal with the fact of the permanence of one instrument with which you were going to be playing?

SS: You can imagine my apprehension, because we recorded the piano-bass-string-quartet stuff without reference to the voice at all. We didn't wear headphones and listen to the voice as we played. We approached the music purely as notes in the air. Most of the time, at some point in the rehearsal, I said the words so the guys would have a sense of the mood that they evoked. I think that did have an effect on everybody's approach to the pieces, but there was no sense of where the voice appeared in the pieces at all, except that I knew.

We played in a room without any headphones or any sense of isolation or a metronome. I had a metronome with me, and before we played I set it and we listened to where the tempo was supposed to be. But at the point we began playing, we just played. As music should, it sped up or slowed down as we responded to each other. So the tapes I was left with when I returned from the recording in Oslo were just some very good music, but I had considerable apprehension that stuff might not fit. That we might have, in the course of enthusiastically playing these things, distorted them past the point where the words would work.

It was an immense relief, one of the happiest of days, when I finally got to laying everything together and found that it worked. That we hadn't strayed too far from the phrasing that I needed to make the coupling with the words successful. I was struck once again at how utterly musical Bob was, how spot-on his speech was. I was amazed at how, without reference to a rhythm section, how thoroughly bebop he was. I'd been aware of that as I wrote this stuff, but actually hearing that with the music was a wonderful affirmation for me that I had been right in thinking that his rhythms and his structures and his way of breathing could generate a very particular, and for me very special, music. I guess "generate" is not quite what I mean. His words contained all that, and it was just a question of extracting what was in there already. I really felt that I wasn't making it up, he was.

AAJ: One of the moments on this record that makes it so hard to believe the story you just told is "Later," which is this amazing sliding-from-line-to-line piece of poetry that stops and starts and continues where you wouldn't expect it to. And the music fits so perfectly, yet not only was he not in the room, but you weren't listening to his voice while you recorded it. I think it's a real triumph on his part and on yours. He was able to evoke something so clearly and you were able to receive it and turn it into music.

AAJ: One of the moments on this record that makes it so hard to believe the story you just told is "Later," which is this amazing sliding-from-line-to-line piece of poetry that stops and starts and continues where you wouldn't expect it to. And the music fits so perfectly, yet not only was he not in the room, but you weren't listening to his voice while you recorded it. I think it's a real triumph on his part and on yours. He was able to evoke something so clearly and you were able to receive it and turn it into music.SS: As I recall, that was a blues. One of two blues on the album, and I could have done a half-dozen blues from the 60 or so selections. And as I said earlier, I'm sure he was not conscious of that when he was writing these poems. But they're unmistakably blues, and the revelation that they were hit me in the head. He wrote blues, and I'm sure at some level that's what he was doing. He'd absorbed the 12-bar blues form over decades of intense listening. I'm sure he would not have been able to describe a 12-bar blues in the technical terms that you need to play a 12-bar blues, but there it was nonetheless. The man wrote a healthy handful of blues in the course of his life as a writer. I think it was no coincidence that I chose a handful of his poems to set as blues, but I sure wasn't thinking about it when I chose them. That became clear to me during the process of writing the album. The album took three or four years to write. I wasn't writing every day, but it took a long time.

AAJ: You mentioned that you had 60 selections, out of which you used 18 for this record. Do you think there's more of this collaboration to come?

SS: I hope I live long enough. It'll be a while. It was 25 years or so between the first one and this one, and I suspect I won't return to it immediately. I'm still trying to clean the slate and to sense what's next. I'm at an impasse. I guess it's a form of post-partum depression. [laughs] I'm not clear where I'll go, but I know I won't go back to his poems. I'll need to do something else. And I suspect it will be several years before I return to them, but I'm sure if I live long enough I would return to them. My only regret is that there won't be a new Bob Creeley book in a couple of years, because for all these decades I've counted on that and been the first guy lined up to make the purchase. That source is lost to me, but there's so much there I haven't yet addressed that I'd hope to get back to it.

Selected Discography

Steve Swallow/ with Robert Creeley, So There (XtraWATT/ECM, 2006)

Steve Swallow/Ohad Talmor Sextet, L'Histoire Du Clochard: The Bum's Tale (Palmetto, 2004)

Steve Swallow, Damaged In Transit (XtraWATT/ECM, 2003)

Hans Ulrik/Steve Swallow/Jonas Johansen, Trio (Stunt, 2003)

Steve Swallow, Always Pack Your Uniform On Top (XtraWATT/ECM, 2000)

Steve Swallow, Deconstructed (XtraWATT/ECM, 1997)

Steve Swallow, Real Book (XtraWATT/ECM, 1994)

Steve Swallow, Swallow (XtraWATT/ECM, 1992)

Steve Swallow, Carla (XtraWATT/ECM, 1987)

Steve Swallow, Home (XtraWATT/ECM, 1980)

Gary Burton/Steve Swallow, Hotel Hello (ECM, 1975)

Selected Poems of Robert Creeley

An online collection of Robert Creeley's work, and more about his life, can be found at the Robert Creeley Archive of the Poetry Foundation.

Photo Credits

Top Photo: Jos L. Knaepen

Bottom Photo: Juan-Carlos Hernández

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.