Home » Jazz Articles » Live Review » Punktfest 2006, Day Two

Punktfest 2006, Day Two

Kristiansand, Norway

August 25, 2006

Day 1| Day 2| Day 3

When British drummer Bill Bruford stepped up to the mic for the first time during his engaging and highly playful duet with Dutch pianist Michiel Borstlap, he made the comment that "as a true road warrior, by all accounts this is an incredibly well-run festival, setting a new high bar for overall competence." And those are truthful words from someone with enough years on the road to know. While organizing any festival, especially where numerous acts will appear on the same stage, is a challenge, Punktfest has to be one of the greatest nightmares from a logistical perspective.

Chapter Index

- Challenges

- Hanne Hukkelberg

- Karl Seglem

- Bill Bruford and Michiel Borstlap

- Frode Gjerstad and Jan Bang

- Bugge Wesseltoft

- The Wagner Reloaded Project (WARP)

Almost every act incorporates electronics to some extent, so just organizing soundchecks so that acts can set up, make sure everything works, and then come back later for the show with the assumption that everything stillworks is a big enough task. Add to that the festival premiere of the Wagner Reloaded Project (WARP)—featuring an orchestra, four sampler/live remixers and more—and it's a wonder that artistic directors Jan Bang and Erik Honoré have had any sleep in the couple of months leading up to Punktfest.

Punktfest may be small in size with respect to attendance (the theater only holds a maximum of five hundred people), but it's big-time in terms of organization—from the people handling the surprisingly large press contingent that has come from around Norway as well as England, China, Japan and, of course, North America, to the folks who make sure that audiences transition between the main theater and the Alpha Room quickly between shows. And all this without the formality and heavy-handed rules that define most festivals with a similar number of artists performing.

Access to artists is simply not an issue—if you don't see them attending the shows, you're sure to run into them at the festival hotel, the Clarion Hotel Ernst. Informality is the defining factor here, and that's another reason why Punktfest is so unique—and so completely enjoyable. Sleep may be a rare commodity here, but nobody seems to mind because everyone is having too much of a good time.

Hanne Hukkelberg

And so, following a diverse and outstanding first day, day two of Punktfest kicked off with Norwegian singer/songwriter Hanne Hukkelberg and her group. When you enter a theater and, along with the usual assortment of guitars, keyboards and drums, you find an upside-down bicycle and a large tin garbage pail center-stage, you know you're in for something different.

Hukkelberg's debut record, Little Things, was released in Norway in 2004, and abroad the following year. Critical praise portraying her as a "most eerie, quirky, beautiful and unusual" artist goes a long way to describing Hukkelberg and her group. In addition to the bicycle and garbage can, her group also includes a variety of more conventional but less commonly used instruments in this kind of context, including banjo, glockenspiel, flute, accordion, an instrument that sounds like a sax but sure doesn't look like one—and, of course, a sampler.

Idiosyncratic like early Bj?rk but not cloying or cute, Hukkelberg's music, like much of what appears at Punktfest, is difficult to categorize. It's a strange combination of beauty and eccentricity. There are all kinds of textures, which are surely considered and well thought out, but never feel contrived. A typical Hukkelberg song might start with a variety of electronic blurps and bleeps, using that tin garbage pail to define a rhythm or a guitar pattern that is taken out of the ordinary by just the slightest stagger. But it may well then transform into a lyrical space where drummer Peter Baden keeps time on a drum kit (which includes a variety of odd things like a metal pail along with the usual gear), and keyboardist Kare Chr. Vestrheim creates a dense string wash that sounds like Crowded House-era Mitchell Froom.

Hukkelberg's voice can range from soft and whispery to surprisingly strong, but it never loses the richness that makes it a treat to hear. Woodwind/glockenspiel player Lena Nymark, like Anne Marie Almedal's backing singer Sigrund Tara Overland, added the "X" factor. In addition to more conventional harmonies, Nymark at times sounded like a singing pigeon being held underwater—but in context it was not only an impressive feat, it was exactly what was needed. One of the emerging patterns with the singers at Punktfest is that English is the language of song, Norwegian the language of speech. As with Garbarek, Endresen and Almedal from day one, Hukkelberg's lyrics are all in English and, while that may be with a clear view to an international audience, none of these artists suffer in the lyric department.

Hukkelberg's music can be complex and episodic or simple and direct. Given the irregular meters in more than one song, there's even a temptation to consider what she does as progressive, but not in the sense of conventional progressive rock bands. Hukkelberg and her band manage to bring together a diversity of influences, however, everything from a Latin vibe to sounds from the deep American South. But it's all filtered through a strangely colored lens that gives even the most lyrical of melodies a skewed feel. "Eclectic" is a term that's bantered about all too often—and unfortunately can sometimes suggest a lack of clear direction. But Hukkelberg's music, despite its diversity, ultimately sounds like nobody's but her own.

While there seems to be a larger market for groups like Hukkelberg's in Europe, there isan alternative scene in North America (including bands like The National and Arcade Fire) which would, no doubt, welcome Hukkelberg's eclecticism.

Karl Seglem

By the end of Karl Seglem's solo set in the Alpha Room following Hukkelberg's performance, six words came to mind: the Hendrix of the Goat Horn. While Seglem is a fine tenor saxophonist, his show focused on two goat horns that have been adapted for playing by a Norwegian instrument maker. One actually has a reed, along with finger holes to change pitch; the other requires more of a trumpet embouchure.

Seglem began his set—largely improvised, and consequently returning the day's music to the spontaneous creation that is one of the festival's foundations—with an extended solo on the reed-based goat horn. During this performance, clearly rooted in Scandinavian folk music, I couldn't help thinking of Jan Garbarek—but a Garbarek who took the early album Dis(ECM, 1976) and continued on from there. Seglem was able to alternate between a lower-register melody and a high pitched pedal tone that gave his improv a harmonic center. But while his first piece began lyrically enough, he began to gradually introduce more unusual elements—whispering and grunting through the horn, taking the piece to places of greater extremes.

On his second tune Seglem improvised over a densely layered track that will be on a forthcoming album this fall, triggered by his Apple laptop (a ubiquitous item at Punktfest). The backing track was a densely layered ambient piece that again had roots in Scandinavian folk music, like his improv.

If Brian Eno were Norwegian, he might make music like this, although Seglem's improvisation was more clearly delineated than the way Eno would likely approach this music. Once again a question comes up about the improvised music at Punktfest: is it jazz? But again, the real question is this: does it matter? Conventional jazz has its roots in the folk music of a different culture, so is what an artist like Seglem does any less valid or relevant?

Switching to tenor for his third piece, he demonstrated a remarkable control over harmonics and the range of the instrument. He often played in a range more befitting a soprano saxophone, but with the tenor's more robust timbre, it nevertheless retained its own distinct voice. Gradually introducing delay, he introduced electronic manipulation, which became more obvious when he introduced a pitch shifter as well. While harmonizing a saxophone is nothing new, Seglem somehow managed to get deeper into the relationship between the notes he played and those that resulted from processing.

Seglem shifted gears again, reading a Norwegian poem over top of a programmed track that sounded like significantly processed acoustic guitars. As the track continued, he finished the poem and picked up his second goat horn, and it's here that the set really took off. On its own, the horn had a plaintive voice that truly evoked the feeling of being lost in wilderness, but Seglem soon began speaking, blowing sheer air and adding some hand percussion.

As the track took on a rhythmic pulse, Seglem kicked in the a distortion pedal and began looping some of his phrases. With an octave divider creating pulsing low notes, he increased the volume, added a wah-wah pedal and began to wave the horn near his amplifier, creating feedback that would have made Hendrix proud. And all this from a goat's horn. No surprise from an artist playing at a festival where technology meets tradition, albeit a tradition considerably different than one might hear elsewhere.

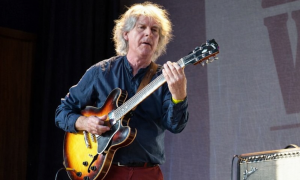

Bill Bruford and Michiel Borstlap

With Seglem's set still ringing in my ears, it was back to the main theater for the most conventionally jazz-centric show of the festival thus far. Still, when Bill Bruford and Michiel Borstlap get together to play—a few times a year, as Bruford described, likening it to dinner with a friend, but not too often, because that friend canbe a challenge—the results are anything but predictable.

It was clear from the start that Bruford and Borstlap were having as much fun playing as the audience was listening—perhaps more. Given that their sets are wholly improvised, the chemistry between them was remarkable. While there were moments where it appeared that one was definitely playing with the other, neither managed to be fooled for very long. Able to literally stop on a dime and pick back up with complete synchronicity, Bruford and Borstlap's playing ranged from dark and abstract to more groove-laden.

Bruford's path has moved increasingly towards this kind of improvisation. While his Earthworks band revolves around a greater sense of structure, Bruford's own playing, perhaps as muscular as its ever been, has also become much more relaxed. It's loose in a way that earlier work, even with semi-improvisation based art rock bands like King Crimson, simply could not support. But Bruford has always been a jazzer at heart—it's just taken him thirty years to get back to it. And while he could be powerful and athletic in performance, he could also be subtle and textural, using a number of different sticks for different effects on his unique, symmetrically configured drum kit.

Borstlap is a perfect foil for Bruford. Versed enough in the jazz tradition to be able to go there if he wants, he's also broadly familiar with other styles—so the duo might lean towards a bluesy feel that almost swung, but then it might switch almost telepathically to something more abstract, and then back again. Bruford's eyes were almost constantly on Borstlap, who split his time between grand piano and Fender Rhodes. There was the distinct feeling that either one could take the music anywhere, and that they were just as surprised as the audience at the sudden turns it sometimes took. It's also entertaining to watch them toss back and forth who should actually start the next improv, and equally interesting to see just how they decide that it's time to stop.

The set covered a lot of ground. But given that both players have a predilection for structure, it's no surprise that their free improvisations sounded more like intentional compositions. Borstlap might find his way to a specific motif that would suggest a rhythmic approach from Bruford. He was also just as likely to deviate from that motif, sometimes subtly other times more dramatically. But the most remarkable thing about the way these players function was how they would find their way back together with no apparent cue. Playing this kind of music requires the confidence to know that a suggested direction will be followed, and that following a suggested direction will never get one into inextricable trouble. Or, perhaps, even if it does, there's always a way out to be found, if one only looks hard enough.

During Bruford's relaxed banter with the audience, he explained how he often thinks up titles to songs that have never been played, in order to give Borstlap a conceptual starting point. In his typically dry manner, he decided to inform Borstlap that the last tune of the set would be called "One Last Chance to Get It Right." A perfect title to end a set where, far more often than not, Bruford and Borstlap both got it right.

Frode Gjerstad and Jan Bang

Following Bruford and Borstlap's clearer compositional approach to improvisation, Norwegian free jazz clarinetist Frode Gjerstad teamed up with Jan Bang for a set that revealed a different side of the same improvisational coin. Gjerstad has worked with artists like William Parker, Hamid Drake, Louis Moholo, Peter Brötzmann and the late Derek Bailey. Those names should suggest that Gjerstad's view of improvisation is more extreme than that of the duo which preceded him. And he didn't waste time, upon taking the stage, to jump into exploring the sonic possibilities of the clarinet. Bang was quick to respond, barely an instant behind Gjerstad, immediately feeding his playing back to him, albeit in a processed form.

As impressive as Gjerstad's playing was, Bang's ability to fit into virtually any musical context was perhaps even more immediate. Some people don't consider a sampler an instrument because it doesn't create its own sound—it needs to take sounds from elsewhere in order to be able to have something to manipulate. But that's a moot point. One only has to watch artists like Bang to realize sampling is more than a technique, it isan instrument. Found sounds can be completely transformed and manipulated—creating, for example, a rhythm from a sample where there was none originally.

The improvised set began in abstraction, with melody a rare commodity and Gjerstad using his instrument more texturally. But Bang gradually created an insistent pulse that provided a strong foundation for Gjerstad. Regardless of the musical context, Bang is never less than completely engaged, and while he would stop/start his rhythm throughout, there was a distinctive visual groove happening on the stage. Proof that it's possible to take the most obscure and free material and fashion it into something that takes on a shape of its own.

Bugge Wesseltoft

As innovative as Bang and his Punktfest partner Erik Honore are, it's possible that Bugge Wesseltoft will emerge as the most diverse artist at the festival. On the first of a two-part concert in the main theater which culminated in the Wagner Reloaded Project, Wesseltoft began as he did during his solo performance on the first day, gradually building a form from where there previously was none. The more one sees of Wesseltoft, the clearer it becomes that exposure to his records on Jazzland only tells a very small part of a much bigger story. His first improvisation came from a distinctly classical space, which was an appropriate approach to open the WARP show—or so it seemed.

As on the previous night, Wesseltoft built his solo from the ground up, reaching a point where he seamlessly began to sample his own work, creating patterns over which he could continue to develop. But on this night he had more of his gear with him, allowing him to do far more. While some of the processed work appeared to come from the stage, he was able to send parts of his sonic manipulations to other parts of the hall, surrounding the audience in sound. In taking a piano phrase, slowing it down and adding heavy reverb, Wesseltoft's debt to Brian Eno can't be understated. Wesseltoft has his own approach to be sure, but it couldn't have happened without Eno's ambient innovations, in this case in particular his groundbreaking work with pianist Harold Budd.

Wesseltoft's second piece began inside the piano, gradually moving from a percussive slapping of the strings to scraping the strings and bringing out odd harmonics. This kind of free improvisation might sound random to some people, but the fact is that there's a lot of work involved in learning how to manipulate the piano with extended techniques like this. Wesseltoft clearly had a direction in mind as he came back to the keyboard and played with a hint of blues and conventional jazz language, demonstrating yet again a knowledge far broader than listeners familiar with his electronica records might suspect. Reaching back into the piano, he created a percussive rhythm that he again sampled and looped, returning to the keyboard for a burst of virtuosity that was by this point not at all surprising—or at all superfluous.

Beginning his final improvisation on a small hand-held percussion instrument resembling a tambourine, Wesseltoft demonstrated incredible imagination in sampling the sound from the instrument and manipulating its pitch to create one of a number of loops that also included sampling his voice and snapping fingers. Once he had built a foundation, he began to solo on a keyboard low to the ground.

As with Bang and Honoré, what becomes evident from watching Wesseltoft perform is just how intimate he is with his technology. To be able to build up a multi-layered piece from nothing requires a kind of understanding of samplers and sound processors that parallels the way traditionalists feel a conventional musician needs to approach his or her instrument. The difference with Wesseltoft is that he is completely conversant not just with his technology, but also with his conventional instrument as well, making his solo performance a unique experience.

But even that was not the full picture. Wesseltoft then brought onstage two separate ensembles—first a wind nonet with two clarinets, one bass clarinet, one contrabass clarinet, two oboes, two flutes and one bassoon; followed by a brass nonet featuring three French horns, two trumpets, two trombones, a euphonium and a tuba. In each case Wesseltoft conducted the ensemble through a composition that blended new music and improvisation—and the line between contemporary classical and improvised music is becoming fuzzy indeed. In the case of the wind nonet, all kinds of interweaving lines split out into improvised portions, to be brought back together on Wesseltoft's cue. The brass ensemble provoked some laughter from the audience; the trumpet players in particular playfully improvised with, well, unusual textures.

The Wagner Reloaded Project (WARP)

It's hard to imagine a project like WARP taking place anywhere but Europe, and perhaps even more restricted to a country like Norway, where young artists like those performing at Punktfest are regularly stretching tradition through the use of technology. Certainly the ambitious idea of bringing together a string orchestra with a group of samplers including Bang, Honoré, Peter Schwalm and turntablist DJ Strangefruit—as well as texturalists like guitarist Eivind Aarset—would be hard to orchestrate anywhere else. It's hard to think of another place where all the required players would be available and interested in such a project, not to mention capable of moving forward with a common purpose.

It's incredibly fortunate that an audience as small as the one at Punktfest could witness this transformation of Wagner's music for the 21st Century. Percussionist Audun Kleive described the project as being "respectful," and from the first notes from Kristiansand Symfoniorkester's leader, cellist Vytas Sondeckis, that respect was instantly clear. The live sampling augmented the natural sound of the string orchestra, creating something that Wagner himself might have considered if he were alive today.

The material ranged from melancholic understatement to the greater drama for which Wagner was well-known. But the music never descended into melodrama, and in fact, the ambient aspect of the entire ensemble's approach brought a greater sense of beauty than a lone orchestra, surprisingly, could create. One of the many highlights was bassist Lars Danielsson's achingly tender solo spot—something that, based on his own quartet's performance the previous night, he was well-suited for.

As has been the case with the festival so far, the lighting was an integral part of the entire experience. More than simply illuminating the stage, abstract images and colors were projected on a large backdrop behind the ensemble, ranging from splashes of color to almost architectural designs. During Danielsson's solo his image was duplicated and projected in a gray scale, which was a very effective way to give him some visibility, since he was at the far back of the stage.

While the processing was used primarily as a textural device, there was a passage where drum programming acted as a strong rhythmic foundation, but even that sounded completely appropriate. And in the final movement, where Aarset's snake-like ebowed guitar meshed with the orchestra's strings, several things became clear. First and foremost, WARP's application of new ideas and tools to old material created a sonic zone where those familiar with the source material could feel comfortable and a younger demographic could be exposed to the classic music in an accessible and relevant way.

The logistics of WARP did not, however, come without a cost. Since the events were running over two hours behind, I had to make the unfortunate decision to miss out on performances by singer Mari Boine and guitarist Fennesz—one of the most talked about and anticipated artists at this year's festival.

Punktfest has one more day to go, though, and a solid lineup that includes Phonophani, Elsewhere, Bernhard Gunter, Arve Henriksen, Tys Tys and a double bill featuring two duos—Nils Petter Molvaer with Deathprod, and Sidsel Endresen with Jan Bang. But amidst a program defined by memorable performances, it's quite possible that WARP will be remembered as a defining moment for the festival.

Visit Karl Seglem, Bill Bruford, Michiel Borstlap, Bugge Wesseltoft, Vytas Sondeckis, Mari Boine, Fenneszand Punktfeston the web.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.