Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Joel Harrison: If You Have To Ask "Is It Jazz?"... It Is

Joel Harrison: If You Have To Ask "Is It Jazz?"... It Is

Jazz is the most democratic of all kinds of music, and I could never do music that didn't have improvisation in it for too long.

Joel Harrison is a busy guy. From his critically acclaimed Free Country (ACT, 2003)—and its resultant commissions and recordings—to his new album of daring arrangements of the music of George Harrison, Harrison On Harrison (High Note, 2005), the 48-year-old guitarist/composer/arranger is constantly looking for news ways to express himself.

Joel Harrison is a busy guy. From his critically acclaimed Free Country (ACT, 2003)—and its resultant commissions and recordings—to his new album of daring arrangements of the music of George Harrison, Harrison On Harrison (High Note, 2005), the 48-year-old guitarist/composer/arranger is constantly looking for news ways to express himself.Harrison sat down after a recent gig at the 2006 Rochester International Jazz Festival to talk about his life, his music, and why it took him so long to make a record that he liked.

All About Jazz: Where did you grow up?

Joel Harrison: Washington, DC.

AAJ: Was there a lot of music in your house? Were your folks big fans or did they have a big record collection?

JH: No, they both liked music, but they weren't musicians, so I would say no.

AAJ: When did you first pick up the guitar?

JH: I guess I started playing when I was nine years old. And I don't really know why I wanted to play guitar. I just did.

AAJ: And where did you start studying? The corner music store?

JH: Exactly. My dad took me down to the place near his office where there were a bunch of old weird looking guys with big ears. They were really scary and wore horrible looking suits [laughs]. They were really patient with me, but it's hard to teach a nine- or ten-year-old kid, and I wasn't really motivated so it didn't last that long. Then a teacher started coming to our house, and at around age 14 I decided that I was really serious about it, and it started to take then.

AAJ: What kind of guitar were you playing?

JH: I started with classical guitar, and I was obviously playing all the folk songs of the day. Then I switched to electric—I didn't switch, I added the electric. At first it was all nylon string, then some things happened. I saw Woodstock: The Movie. And the electric guitar is really an inevitability of this day and age. All the students I teach want to play electric guitar. Even when their parents make them start on acoustic guitar, they always switch.

AAJ: When you were 14 or 15, did you see something that made you say, "Now I'm going to be serious about it"?

JH: It was a combination of things. I think the music that was really in the air at the time involved people using the electric guitar in ways no one had ever seen before. At that time, people were creating something truly new, and I think people forget that about rock music. At one time, it truly was avant-garde, and it got created in a time of incredible turmoil and passion. People like Jimi Hendrix and Pete Townsend—I was a kid when I saw them, and the effect they were having on the culture was just devastating. Also Simon and Garfunkel, of course much more acoustic. The music of that time was incredibly powerful, and really stood out in the society at large, and it was impossible to ignore that.

AAJ: What changed when you decided to be more serious?

JH: It was a feeling of destiny. "This is what I'm going to do." And I started to model my identity around that and to practice harder.

AAJ: Did you find a new teacher then?

AAJ: Did you find a new teacher then? JH: No. I didn't really have very good teachers. I wish I had. Perhaps it was limited where I lived—I don't know. I had the same teacher all through high school. I had a lot more teachers after that, so I made up for it.

AAJ: Were you playing in a band in high school?

JH: Oh yeah, of course. I was doing all that stuff.

AAJ: The obligatory garage rock band?

JH: Well, we were playing songs by Yes and the groups of the day. Hendrix, Eric Clapton.

AAJ: When you went to Bard College, you were part of Karl Berger's Creative Music Studio scene at some point, right?

JH: That was such an incredible place. In a way, that could never happen again, because all the people he had teaching there were part of something—like rock music was to the 60's—the creative jazz movement in the 70's, which was part of the loft movement in New York. There were just a lot of fascinating, weird individual players on the forefront of this new jazz that [Berger] would have up to teach there.

I didn't spend much time there, but I saw some incredible stuff. I went to an Art Ensemble of Chicago 10-day workshop that was really life changing. Their mixture of types of different music, and what influenced them, and their stance, the way they looked at the world, how strong their personalities were—it was just so affecting. And they were really amazing teachers, too. I learned an awful about what it means to improvise in that short period of time.

AAJ: Did you learn by doing?

JH: Yeah. They had workshops and really interesting ways of approaching teaching. Roscoe Mitchell had a class that he did where he would have everybody just sit in a circle, and there were no rules except one: You had to be in tune with what was going on. He would be the judge of that. And the moment somebody played something that didn't seem to fit what had been created for it compositionally, he'd snap his fingers and we'd have to stop and start again. I don't think we ever got beyond a minute of music.

AAJ: That must a been an ego-challenging experience.

JH: It was, but I think it was fantastic training. This was coming right from the source. He wasn't messing around. It was like, "This is deadly serious. You think free improvising is just fucking around? No."

AAJ: How did that mesh with what you were studying at Bard? I imagine that was a pretty different environment.

JH: Yeah, but I always wanted to learn about everything. So while I was always interested in pop and rock music, I was also interested in straight-ahead jazz and serious composition. I was studying composition. I was taking a lot of dumb and useless courses at Bard, to be honest, because it was kind of a flaky place at that time. But the best thing I was doing was studying composition with Joan Tower, who's now become very well known. She was a great teacher.

AAJ: While I was listening to you last night [June 11, 2006 at the Rochester International Jazz Festival], I heard a woman lean over to the guy next to her and say, "Is this jazz?" And I remembered this thing that you wrote earlier this year: "There are still people who act as if the intersection of, say, rock and jazz, or Chinese folk song and jazz, is odd or unusual and I find that amazing." And I know that even back in '79, you and [percussionist] Sonam were doing the Native Lands (Minds on Hold, 1979) record, and you were exploring things back then.

JH: You're probably one of the seven people on earth who's heard that record.

AAJ: It has its charm.

JH: Primitive charm.

AAJ: Can you talk a little more about that embrace of different styles and genres and their applicability to jazz?

AAJ: Can you talk a little more about that embrace of different styles and genres and their applicability to jazz? JH: To me, that's what jazz always represented—a strong tradition but also a kind of music that would welcome any influence into it, as long as you could figure out how to do it in a way that was musical. In general, my outlook toward music is very ecumenical. I love all kinds of music, and I think that comes out in whatever I do. I'm a believer that jazz is not a pure form of music and never was. It's all about what you decide jazz is. There's not much of a common denominator.

So I just take what I really love and learn enough about it so that it's absorbed into my system, and then I do what I do. And whatever comes out, maybe it leans toward something that's more unstructured and free, like from the old days with the Art Ensemble of Chicago, or maybe it comes from just a simple place with no composition, or maybe it's an elaborate composition with no improvisation, or maybe it's swinging. Although I'd say that's pretty rare.

But I think if I sat there and pointed out to you why that's there and why this is there you'd say, "OK, I get it," because these are really definite parts of my past that relate to everything I'm doing. Hopefully you don't notice that. You just have an experience. But if we sat down and picked it apart, you'd see that little African guitar thing, I got that from listening to African music. And that solo that guy took, the reason I love that solo is because it comes from this lineage that I'm a big fan of. That's so funny. I'm so glad you overheard that [question asking "Is this jazz?"]. That's classic.

AAJ: Anyway, when the woman asked "Is this jazz, her companion's response was "yes," which is nice.

JH: What piece was it?

AAJ: It was during [George Harrison's] "Beware of Darkness." Which, to me, wasn't even the best time to ask that question.

JH: Yeah, that's a much more normal tune. That's just a melody and some really beautiful chord changes. That's a song that people really love, because the harmony easily applies itself to a more straight-ahead jazz reading.

AAJ: I'm not sure she meant it like, "I know what jazz is and I'm having a hard time fitting this into my cosmology." I think she was asking from a place of interest.

JH: But what's so weird about the world is that as far back as the early 70's, there was Miles Davis doing Jack Johnson (Columbia, 1970). That's now 40 years ago. I mean since when is rock and jazz coming together that different? I just think most people hear many different kinds of music. Even when you play a major festival like this, there's a sense that you do something like that and people are a little bit shocked or surprised and maybe ambivalent about it.

We [Harrison's band] live in our little world. We think what we're doing is normal. One of the things that really surprised me last night was that even my friend [guitarist] Steve [Greene] and Sonam both used the word avant-garde to describe what we were doing. These are both knowledgeable musicians. I never consider myself avant-garde although I really can see how elements of that are part of who I am. But most people would never pair me with Matthew Shipp or William Parker or Evan Parker. They would think I was way, way more normal than that. But in a way I started to see that the way we pick apart these tunes and what we do with them can be so unpredictable and so unusual that people might think that. Some of Dave Binney's solos were screaming atonal solos, and the textures we do are really freaky, weird, psychedelic textures, so I began to see that maybe you could think of it that way.

AAJ: During the evening, I saw some friends who had been at your first set, and who said it took them a while to get over the fact that it was called "Harrison on Harrison," and that they had to adjust to this not being a performance of BeatleJazz.

AAJ: During the evening, I saw some friends who had been at your first set, and who said it took them a while to get over the fact that it was called "Harrison on Harrison," and that they had to adjust to this not being a performance of BeatleJazz. JH: That totally makes sense, and this project is a mixed blessing in that sense. First of all, I think it would be easy for a real serious musician to look at the fact that I was doing anything by the Beatles and say, "What a sellout." Because typically you would expect a really lame record. So on that end you have some problems, and then on the other end you have people who genuinely want to hear a really normal rendition of their tunes coming in and going, "What the hell is this?" To me, if people would just listen to the music and realize that jazz is all about taking something that in general is very simple and a powerful seed for improvisation and then really approaching it creatively. That's all this is. You can almost use anything.

AAJ: You've said that [the Beatles'] Rubber Soul (Capital, 1965) was the first record you ever bought with your own money. Were you surprised by what you found when you delved so deeply into George Harrison's music later in life?

JH: I don't think I was exactly surprised. I was pleased that I felt so emotionally connected to the music, and it made me want to play it, and that's always a good feeling. And I was pleased that the arrangements that I came up with for that first concert [when Harrison was commissioned to arrange works by George Harrison for a tribute concert] tended to bring out good things in people and create interesting possibilities.

AAJ: I want to ask more about what you're doing now, but I also want to make sure that there's not a 30-year gap in the story...

JH: Between when I was 12 and 48?

AAJ: Exactly. So let's fill in that gap. What did you do after you left Bard College?

JH: I moved to Boston and lived there for five years, and did a variety of things in Boston and played different kinds of music.

AAJ: Why Boston?

JH: I think it was mainly because I had a bunch of friends there, and I thought it would be good to play music with them. I'm not sure it was the best choice. I kind of wish I'd just gone straight to New York, but I didn't.

AAJ: What did you do after Boston?

JH: I moved to the Bay area for 12 years—I lived in Berkeley. It was kind of an interesting time out there. At that point I was really into this world music thing that you hear some of on Native Lands. I studied music at the Ali Akhbar Khan school. I was learning African music. I would go out and buy music from all over world and just try to learn about it, and that was more meaningful to me than jazz at that point, so I fell out of jazz for a while.

But a few years later, after being out in the Bay area, I was writing a lot of songs, and I more aspired to be a Paul-Simon-type character, somebody making music that had a variety of influences. But at a certain point I realized I couldn't grow as a musician in this type of music that I had chosen to pursue. I needed a substructure that was so strong and so based in tradition that whatever else I did I could fall back on that, and that's when I really seriously started studying jazz. I knew a lot about jazz, and I'd worked with it before, but I realized that in order to get to where I really needed to go, I needed to anchor everything in that tradition.

AAJ: Because of your personal connection to it? Couldn't you have picked, say, Ali Akhbar Khan's tradition and based your music on that?

JH: No, I don't think I could have. That's why I love jazz so much. If you learn enough about jazz, then it will welcome other parts of who you are into it, whereas that's not true of Indian classical music. And at the time, I didn't believe that was true of Western classical music, although I think that's changed. I think that's somewhat true. But jazz is the most democratic of all kinds of music, and I could never do music that didn't have improvisation in it for too long.

AAJ: When you were in the Bay area, is that when you got involved with film scoring?

JH: Yeah.

AAJ: One thing about film music I've always dug is that is seems to force you to find the essence of a particular sound. Your track "Southern Comfort" [from Harrison's CD Film Music] as soon as you hear it, you know what it's about. Is that a useful tool for you?

AAJ: One thing about film music I've always dug is that is seems to force you to find the essence of a particular sound. Your track "Southern Comfort" [from Harrison's CD Film Music] as soon as you hear it, you know what it's about. Is that a useful tool for you? JH: I think so, because you have to do a lot in a very short period of time, and you have to create a very strong point of view with film music, and I think it helps your writing.

AAJ: What was your entrée into film music?

JH: I had a friend who was making documentaries for A&E and CourtTV, and he invited me to do the music.

AAJ: What did you think about the invitation?

JH: I was really glad to do it. Not always, but it was good money and a good challenge.

AAJ: Did you write for other ensembles?

JH: No, this was largely synthesizer-based music with a little home recording thrown in.

AAJ: You came to New York in 1999. Why did you decide to make that move?

JH: Well, in the Bay area there were some pretty powerful years there, when there were a lot of great people out there and there was really the feeling of a scene and something happening. Maybe 1994-98. And I'm really proud of the records I made out there, which most people have never heard of—Range of Motion (Koch, 1997), Transience (Spirit Nectar, 2001), and 3+3=7 (Nine Winds, 1996). I like to mention those, because I think people think that all I've ever done is Free Country and Harrison on Harrison. I've been around for a long time and done a lot of composing, and I wish people knew more about those records. But it just became clear that there was a glass ceiling in the Bay area for what I wanted to do, and it took a lot of nerve to pull up stakes and come to New York, but I'm really glad I did. It's been very, very fruitful for me.

We were talking about bringing together different styles of music. I had this experience when I was maybe 25 of sitting in on a poetry class by Robert Duncan. It seemed to me at the time, listening to him talk, that he had absorbed so many different influences from poetry into his own writing, and I thought, "How does he do that?" Because I felt like all the different things that I liked, I couldn't figure out how to bring them together. Everything ended up sounding secondhand, or just plain trite. And I went up to him afterwards and I walked with him for a little while and I said, "I'm having this problem. I love all these different things, and I have no idea how to make them fit together."

He said, "Well, first of all, I wouldn't even think that what you're trying to do would be possible until you get older." He said before he was 30, he had the same problem, and he said, "I didn't even begin to be able to convincingly develop a voice that involved the different things that I loved until after I was 30." He said a lot of other stuff, but that really stuck with me. I took me so long to put out an album that I liked. My first record didn't come out till I was in my late 30's, and it's because it took me so long to figure out all these different influences.

All these things I was studying needed time to gel inside me, and I needed to seriously understand them and not just be a dilettante for it all to become music as opposed to concepts. And I think that's one of the things that is the difference between eclectic music that just sounds superficial, and eclectic music that works on some deep level because people have devoted themselves to whatever sources their music is coming from. It really takes a while. Anybody who's following what you're doing has to have a lot of patience, because it can really take a while or be hit-and-miss.

AAJ: Will you talk about how [reed player and Oregon member] Paul McCandless came to be in your orbit? [McCandless appeared on Range of Motion]

JH: He lived in the Bay area, so he was an obvious choice for this texturally rich eight-piece band that I was writing for. He's just phenomenal. He's almost the only person who does what he does, which is to double on single-reed and double-reed instruments, and he was the first person I recorded with who was at that level. He was so fantastic, so easy to work with, and so good at what he did. Oregon was a big influence on me when I was about 18—talk about people who were creating a new synthesis of sound. So it was very exciting for me to have him be a part of that.

AAJ: What about him as a player or person was at a higher level?

AAJ: What about him as a player or person was at a higher level? JH: He came in to record, and he was obviously completely in control of what he was doing. Guys like that, there's a certain gravitas that they bring with them, like, "I've done this so many times, so no worries. It's going to sound good, and it's not going to take me a long time to make it sound good."

AAJ: I really like 3+3=7. I like the sound, and the interplay between the three guitarists and two drummers, and the fact that that many fingers are able to come off sounding as good as they do, it seems like a large victory. How did you come up with the concept for that record??

JH: At the time, I really felt stuck in ways of making music that seemed kind of old to me. Conventional song structures, head-solo-head forms. I reconnected with my friend [guitarist] Nels Cline, who I'd known at Pamona College and stayed in touch with. When I moved to the Bay area, I started to see him more. He's always been someone who inspired me. I knew [drummer] Alex Cline, too, and I thought I'd like to do something that I've never done before, and just throw open the gates to what's possible.

[Nels] had the Alligator Lounge music series in L.A., which was a way you could improvise and do new things without much concern about any of the typical things that you have to worry about when you're playing a gig. So we did a quartet concert with two percussionists and two guitarists, and it suggested to me that if I added one more of each it would take it into a place that I'd never been before. I believe that electric guitars can do many different kinds of things. You can create so many different kinds of textures and sounds, and if you combine that with my love of world music and world percussion ... [3+3=7] is a record that really touches on true avant-garde improvising with rock and roll, world music, and psychedelic stuff. In a way, I've been doing the same thing over and over again, but in really different ways. That's the only record I've ever done where there was extended free improvisation. It was really a lot of fun.

AAJ: Let's take that final step to the modern era. Free Country was obviously a big record, and my guess is that it introduced people to Joel Harrison who hadn't know much about you before. You mentioned earlier that the Harrison on Harrison album was a blessing and a curse. Was Free Country a similar experience?

AAJ: Let's take that final step to the modern era. Free Country was obviously a big record, and my guess is that it introduced people to Joel Harrison who hadn't know much about you before. You mentioned earlier that the Harrison on Harrison album was a blessing and a curse. Was Free Country a similar experience? JH: Yes, very much so. It was really kind of a fluke, and it brings to mind that John Lennon line about life being what happens to you when you're making other plans. I'd been playing some of those country tunes and just enjoying that, and it suggested itself as a project at a time when I didn't have a strong feeling about what else I wanted to do. I put out Range of Motion and Transience, which were both my compositions for elaborate, larger bands, and I thought I was in a transition in my life.

I'd just moved to New York, and I wanted to do something simple. But in a way I almost looked at it like a throwaway project, something nobody would notice, but it would be fun. I'd print up a few copies and move on. And it just seemed to have a life that was bigger than that, partly, though not all, because [vocalist] Norah Jones was on there. And it ended up being my most successful record by an enormous factor. I think there are a lot of reasons for that. Partly that no one had done anything like it before, even though it's apparently similar to certain artists' approach to country and jazz, but not really. Also the strength of those songs, and of course the personnel. And a good record company putting it out.

AAJ: And it's led to other projects?

JH: Yeah, there was Free Country 2 [So Long 2nd Street (High Note, 2004)]. I felt like the first one was such an accident that I wanted to approach the second one as if I was actually planning it. I played a lot in Europe doing that music. And I sort of see the Harrison on Harrison project as the final piece in that body of work, which is essentially arranging, even though there's some of my writing on there. I'm still waiting for somebody to call me up and hire me as an arranger. I thought that would happen, but it hasn't. So, anybody out there? Any singers need a new way of approaching music?

AAJ: You and [saxophonist] David Binney seemed to be a perfect match at last night's show. He would spend so much time exploring one pitch with overtones, and I was really enjoying how much you guys seemed to dig being up there together.

JH: I think we share a musical aesthetic, which again is very eclectic. I think one of the things we've all learned to do over the years is approach improvising from a lot of different ways. He's got a tremendous vocabulary, and it's not just the technical stuff, although he's an amazing technician.

But like you said, he can also play incredibly simply, which for a country music project can be really effective, because sometimes you don't want that tired jazz phrasing. You want somebody to play really simple melodies. He also loves electronic music and rock and roll and funk, and he can play in any style of jazz you throw at him. It's great as a bandleader to have somebody who is that able to accomplish what you need, no matter what you put in front of him.

But like you said, he can also play incredibly simply, which for a country music project can be really effective, because sometimes you don't want that tired jazz phrasing. You want somebody to play really simple melodies. He also loves electronic music and rock and roll and funk, and he can play in any style of jazz you throw at him. It's great as a bandleader to have somebody who is that able to accomplish what you need, no matter what you put in front of him.AAJ: And how about [bassist] Dave Ambrosio and [drummer] Dan Weiss?

JH: Dan is getting better known now. He's a great drummer and very good tabla player with a really unique approach to the drums. Again, a phenomenal technician, but also conceptually, he's always thinking out of the box. And the same is true for Dave Ambrosio.

AAJ: What's next for you?

JH: I've got two commissions from Chamber Music America, which is really exciting. One is a Doris Duke composition grant, where I'm writing a piece for the group Free Country plus cello and violin, and also involving text, where I'm interviewing people and asking them to respond to questions like "Who are you?" and "What does it mean to be an American?" and "Where is our country headed?" and then making the text part of some of the movements of the piece. That's all original music, so the influence of country or Appalachian music will be more felt than heard.

Then I'm doing a French-American jazz collaboration that's a first-year project for Chamber Music America, where I'm working with French-Vietnamese guitarist Nguyen Le, percussionist Jamie Haddad, [French] bassist Gildas Bocle, and Dave Binney, and we're going to make a record that has original music as well as interpretations inspired by French and American icons like [French composer Olivier] Messiaen and [American composer Charles] Ives and French troubadour song and Cajun music.

AAJ: How did that project come about? Was the French influence your idea?

AAJ: How did that project come about? Was the French influence your idea? JH: No. There was a grant that I applied for that Chamber Music America started with the French government to have French-American collaborations. I was a fan of Nguyen Le for a while, and thought it would be interesting to have two guitars. Again, here's a guy [Le] who deals with all these different kinds of music, so I created an idea for a project.

AAJ: And will the end product of both those things be recordings?

JH: I hope so. Definitely. Although I've got so many projects I want to record now, I don't know when or how they're all going to come out. I know High Note wants to put out the French-American one. I've also got a CD I'm finishing of songwriting, where I sort of came back to who I was 15 years ago, but from what I know now. I love that music, and I want to try to get that out there, too. I'm not exactly sure how to do that.

AAJ: Is that with musicians other than the guys you normally play with?

JH: Some of them are similar, but there is a different band to some degree. But Stephan Crump is on bass, Ben Whitman on drums, Jamie Haddad, [organist] Gary Versace plays a lot.

AAJ: Is there anything I didn't ask you about that you want to say?

JH: Just a quote based on your experience last night: If you have to ask "Is it jazz?" ... it is.

AAJ: I'm putting that on a t-shirt. Did you just improv that right now?

JH: Yeah.

AAJ: That's fantastic.

JH: Maybe that could be the name of the article. The main thing for me is that I'm just so privileged and so happy, despite all the vicissitudes of being a musician, to be a musician, because our world is so troubled. There's such ignorance and conflict everywhere you look, and I really believe, the older I get, that artists are one of the main groups holding the line between culture and chaos. Not individually, but collectively what we do is helping the world in a small but enormous way. All of us have to keep devoting ourselves to that, because it really makes a difference. It's not noticeable day to day, but the world is just completely unhinged, and an artist's job is to keep that from happening in every way they can, and to make sense out of all the chaos.

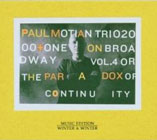

Selected Discography

Joel Harrison, Harrison on Harrison (HighNote, 2005)

Joel Harrison, So Long 52nd Street (HighNote, 2004)

Joel Harrison, Free Country (ACT, 2003)

Joel Harrison, Transience (Spirit Nectar, 2001)

Joel Harrison, Range of Motion (Koch International, 1997)

Joel Harrison, 3+3=7 (9 Winds, 1996)

Joel Harrison & Sonam, Native Lands (Minds On Hold, 1979)

Note: Harrison has also released two self-published titles outside the jazz realm, a singer-songwriter EP called Passing Train and a collection of his film music titled Film Music, Volume 1. More information is available at his website.

Photo Credit: Joerg Grosse Geldermann / ACT Music

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.