Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » Has Katrina Failed to Blow the Wool from over our Eyes? ...

Has Katrina Failed to Blow the Wool from over our Eyes? Why I Disagree with the New Jazz Orthodoxy

Our peculiar lack of historical consciousness is the apt companion to the lack of vision inherent in the discourse around 'rebuilding' New Orleans.

The recent disaster in the Gulf region is not only historic, but mythical; it provides a window into our political, economic and social life and also our ideas and fantasies about who and how we are. Not surprisingly, in a nation which is infamously self-congratulatory and completely sentimental about its own history, this disaster and its consequent reactions are framed in a narrative that chooses to emphasize individual heroic efforts over systemic racism and class-based oppression; fiscal and managerial mishaps over the institutional ravages insured by modern day capitalism; the laudatory tweakings of a bourgeois, liberal democracy over the imperialistic domination its affluent lifestyle is based upon; and evidence of a fictive melting pot culture over the widening alienation and vicious behavior between various "Americas.

The recent disaster in the Gulf region is not only historic, but mythical; it provides a window into our political, economic and social life and also our ideas and fantasies about who and how we are. Not surprisingly, in a nation which is infamously self-congratulatory and completely sentimental about its own history, this disaster and its consequent reactions are framed in a narrative that chooses to emphasize individual heroic efforts over systemic racism and class-based oppression; fiscal and managerial mishaps over the institutional ravages insured by modern day capitalism; the laudatory tweakings of a bourgeois, liberal democracy over the imperialistic domination its affluent lifestyle is based upon; and evidence of a fictive melting pot culture over the widening alienation and vicious behavior between various "Americas. In his recent article published in Time, "Saving America's Soul Kitchen: How to bring this country together? Listen to the message of New Orleans, Wynton Marsalis, our de facto national voice of jazz, addresses the nation, rightly admonishing us to consider the cultural worth of New Orleans through its cuisine, architecture and music (well actually, he seems interested in only one strand of New Orleans music). And while he urges us to see the mythic scale of the current crisis, his choice to view New Orleans' place in the nation's soul only through the lens of culture continues a long tradition of comfort with creating myths that hide much more than they reveal about our national character. He laments that Americans "have never understood how our core beliefs are manifest in culture—and how culture should guide [our] political and economic realities. Culture/politics/economics are part of a whole in life and must be considered together if our lived experience is to progress towards our highest ideals.

What Marsalis fails to acknowledge is that many in America care no more about saving America's "soul kitchen than it does for the liberation of Uncle Ben or Aunt Jemimah. While Marsalis in his celebration of the cultural triumphs of the "Big Easy fails to mention injustice and inequality, white America and black America (to cite only two groups) differ in their perception about the salience of race and class in this crisis.

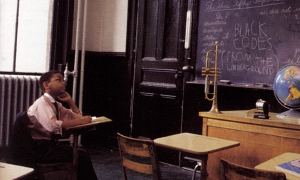

One way to insulate oneself against the blindness necessary to be able to disagree on something so palpably obvious is to realize that many Americans, especially the black poor, have been in a perpetual state of crisis, a state that is dramatically highlighted by the grand scale of what is only the most recent massive dispossession. The color-blind ideology implicit in his [New Orleans-centric] version of "the birth of jazz story ignores the bitterness and fractiousness that existed between the so-called races of New Orleans musicians and the ways that it has affected the music.

For instance, Ferdinand Joseph La Menthe, the great Jelly Roll Morton, showed great resentment to his demotion to de facto blackness. In contrast, Sidney Bechet, who also grew up as Creole and spoke French in his household, identified as black. In his autobiography, Treat it Gentle, Bechet identifies himself and jazz music as being African. His myth of origin story about jazz differs from Mr. Marsalis' considerably in this regard. Bechet's myth has jazz, African music made American through the crucible of slavery, told in a remarkable romance that includes, slave owners, slaves, maroon communities, psycho-sexual expressions with respect to race, dismemberment and loss, disenfranchisement and other topics of historical and cultural significance.

Maybe his generally being overlooked as a pioneering early jazz soloist (honors universally awarded to Louis Armstrong) and the even more egregious oversight as [one of] the first great saxophonists in the tradition (honors that "properly belong to Coleman Hawkins) is related to his politics. How might our views of the music's meanings and aesthetics be different if Bechet's example was as canonical as those of Pops or Jelly Roll?

Marsalis points out the injustice of "[t]he genuine greatness of Armstrong [being] reduced to his good nature. But does not the ease of this reduction stem from political and economic realities that informed the culture, just as much as the culture informed the political economy? It is the willful refusal to incorporate this truth into art that is the biggest weakness in the aesthetics of the nearly triumphant neo-conservative movement in modern jazz.

If it is true that jazz embodies, as Marsalis puts it, a "flowering of creative intelligence brought about "where elegance met an indefinable wildness, it is also true that at its best jazz has historically critiqued American hegemony through its blues-based revolt against the strictures of Western aesthetics. In a deal with the devil, jazz is threatening to become respectable with the full trappings of mainstream institutional support. The not-so-hidden costs of this deal include: redefining jazz as America's sole (just ponder the chauvinism required simply in the use of that adjective here) art form, rather than as an African-American art form, the reification of certain styles and artifacts over the processes and dynamic interactions of the music and the acceptance of liberal bourgeois ideology over the revolutionary aspirations of earlier generations of jazz musicians. These are hefty costs indeed and if paid in full will rob the United States of one of its historically rich voices, a potential resource in the humanization of a nation that values commodities over people.

It is our "me first and damn the world attitude that has earned us the disdain of much of the world. It is so pervasive that we lapse into its grasp sometimes even when we are trying to provide a prophetic voice. Of course, I applauded Kanye West for lamblasting the Bush administration for its racism and felt good about the philanthropic gestures of some of the wealthy athletes and artists. But I wondered about the lack of substantive critique of the American empire from the hiphop community in a time when the decadence of American culture and the viciousness of its politics have landed us into the beginnings of World War Three.

Perhaps the willful ignorance and apathy of our artists only mirrors the historical amnesia of a people who act surprised at the New Orleans crisis despite the clear example of the putative worth of the black poor as revealed in the Mississippi flood of 1927, where blacks were forced to repair the levee at gunpoint and were mistreated in rescue camps. Our peculiar lack of historical consciousness is the apt companion to the lack of vision inherent in the discourse around "rebuilding New Orleans. Musician/scholar/activist Fred Ho raises the central issues that should be taken into account when he questions "the notion of rebuilding a defective New Orleans in which the wetlands were degraded and eviscerated, in which the ocean surrounding the coast has become a 'dead zone' devoid of oxygen and nutrients to support marine life due to the scarring and pillaging by oil rigs and pipelines.

The disregard of environmental needs when they interfere with profits is mirrored in the arrangements where the revitalization of tourist district is the key of the restoration plan, rather than focusing on how to incorporate humanitarian values in city planning. We know that this country loves black music more than it loves black people, but our representative artists should not be blindly complicit in this.

It is not possible to rebuild culture, history and community per se. These things are not planned anyway. What is possible is really to examine how we can excuse the failure of our political will and our government's administration to prepare for a disaster that was inevitable and foreseeable. We could confront the self-image of a nation that always holds the morality, civility and ultimately the humanity of black people in question. If this is a tall order for a nation that cannot muster appropriate outrage against an administration that steals elections and takes over countries, it is also a stretch for the spiritual resources of an aesthetic that hides its head in technical brilliance over truth seeking and institutional respectability over revolutionary zeal.

Discuss "Has Katrina Failed to Blow the Wool from over our Eyes?" on the AAJ Bulletin Board.

Originally from Detroit, tenor saxophonist/flutist, composer, author and historian Salim Washington is also a specialist on Romare Bearden and African American Art. His sole release as leader is Love In Exile (Accurate, 1998).

< Previous

Arrive

Next >

True Nature

Comments

About Salim Washington

Instrument: Saxophone, tenor

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.