Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » How Far Is Too Far Out?

How Far Is Too Far Out?

When listening to free-form avant-jazz, it may seem like anarchy rules, but if you listen closely, there are many things happening at once and they are happening with a purpose in mind.

In every age of musical advancement, the musicians who sought to raise the bar were met with outrage and disdain. The musical world and society at large were not ready for change.

Change is difficult. When John Coltrane came along playing slightly out of tune and re-harmonizing diehard standards, the critics went nuts. When he added Eric Dolphy to his famous quartet, the musicians complained and the critics criticized again. They didn't understand Eric's polytonal approach, but John did. They just didn't get it. Go back and read some of the old Downbeat reviews and you will see how angry some of them got. Both John and Eric were considered the "out" cats then, but at the same time Ornette Coleman arrived from Texas with his plastic saxophone playing with his Harmolodic approach. Wow! That was very out—for that era. At the same time, there was a pianist by the name of Cecil Taylor sitting in a downtown coffee shop that no one wanted to play with because he was absolutely non-musical and crazy and no one could relate to anything he played. When Trane moved from Bebop to modal playing he was eventually accepted, but when he moved on to his free-form Avant-garde out playing, he was ridiculed. Yet he was the only one who understood and believed in what Albert Ayler (another apostle of "spiritual out-ness") was trying to do.

Change is difficult. When John Coltrane came along playing slightly out of tune and re-harmonizing diehard standards, the critics went nuts. When he added Eric Dolphy to his famous quartet, the musicians complained and the critics criticized again. They didn't understand Eric's polytonal approach, but John did. They just didn't get it. Go back and read some of the old Downbeat reviews and you will see how angry some of them got. Both John and Eric were considered the "out" cats then, but at the same time Ornette Coleman arrived from Texas with his plastic saxophone playing with his Harmolodic approach. Wow! That was very out—for that era. At the same time, there was a pianist by the name of Cecil Taylor sitting in a downtown coffee shop that no one wanted to play with because he was absolutely non-musical and crazy and no one could relate to anything he played. When Trane moved from Bebop to modal playing he was eventually accepted, but when he moved on to his free-form Avant-garde out playing, he was ridiculed. Yet he was the only one who understood and believed in what Albert Ayler (another apostle of "spiritual out-ness") was trying to do.

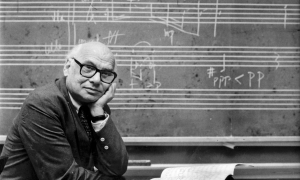

Looking back, we wonder: "what was all the fuss was about?" Ornette is still going strong and accolades have been bestowed upon him from all over the world. There is an established Church of John Coltrane and practically every tenor saxophonist from 1970 on has tried to emulate him. The misunderstood Thelonious Monk has been escalated into a God. His music is a required study for anyone who studies jazz. There has been a resurgence of Albert Ayler and Eric Dolphy's music. Along with the re-discovery of both saxophonists there seems to be a new CD of newly-discovered recordings released every few months. Fans wait for hours to hear Cecil Taylor play. There are festivals and radio programs dedicated to these "Icons of Music" all over the globe. One of the most respected modern musician/composers of our day, Anthony Braxton, continues to record and perform offering the world a glimpse into his mind.

The New York City loft scene that went underground in the seventies has re-emerged as "the downtown scene". Downtown New York City clubs such as Tonic, The Knitting Factory and the Sunday Night Avant & New Music Series at CBGB'S present some of the very best of the avant-garde players in the world. In the last few years the scene has extended to some venues in New York City's borough of Brooklyn. On the "Left Coast", players such as Vinny Golia, Nels Cline, and Henry Kaiser are part of a handful of musicians who are keeping the flame alive. So why in this era of mediocrity in music— and almost everything that surrounds us in the arts—is there such an outcry against an art form that seems to have proven itself through the years with quality musicianship and outstanding originality, but is not truly accepted as a form of Jazz?

The New York City loft scene that went underground in the seventies has re-emerged as "the downtown scene". Downtown New York City clubs such as Tonic, The Knitting Factory and the Sunday Night Avant & New Music Series at CBGB'S present some of the very best of the avant-garde players in the world. In the last few years the scene has extended to some venues in New York City's borough of Brooklyn. On the "Left Coast", players such as Vinny Golia, Nels Cline, and Henry Kaiser are part of a handful of musicians who are keeping the flame alive. So why in this era of mediocrity in music— and almost everything that surrounds us in the arts—is there such an outcry against an art form that seems to have proven itself through the years with quality musicianship and outstanding originality, but is not truly accepted as a form of Jazz?

Europeans have accepted American jazz as an art form without hesitation and prejudice. They welcome American avant-garde artists to their shores with open arms. Why do you think that is so? To understand this phenomenon, you must look back at European musical history. Europe is the land of Bach, Brahms, Mozart, Beethoven, Handel, Chopin, Wagner, Schoenberg, Berg, Ravel, Bartok and many many more. By the time Western European music had reached the 20th century, the European musical ear had grown and was adjusting to dissonance. It was a natural growth for them; and yes, sometimes there was an outcry about the music. Witness the outrage and the riots that occurred with the premier of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring—now considered a musical masterpiece.

Here in America the avant musicians blame the critics and the record companies for not promoting this kind of music as Jazz. Most avant players call themselves "improvisers" not jazz musicians. They are so angry at the way they have been treated by the public and the "straight ahead" jazz musicians, they would rather have it said they play "improvised" music or even "world music", and some adamantly deny they are jazz musicians! The truth is that most of the public isn't aware of jazz artists no matter what kind of music you call it. "Jazz" has so many categories now, you have to be a musicologist to keep up. Some well-known and influential jazz radio stations in the U.S. will not play artists like Albert Ayler, Eric Dolphy or present day David S. Ware, Nels Cline, Anthony Braxton, Matthew Shipp, Dom Minasi, or Peter Brotzman. In order to hear these, and many other artists, you must tune into the alternative stations. So the question is: How far out is too far out?

When you listen to Cecil Taylor play or some of the new crop of musicians that has sprung up from his influence, what do you hear? Some say you hear "noise" but, if you listen carefully, you will hear a musical exploration. There is always a relationship between what the soloist plays and what the rhythm section plays. In the case of a solo instrumentalist giving a solo performance, the same applies; except the relationship is between the player (his mind & spirit) and what is being related to an audience and how the audience relates to the player. There is a constant underlying feedback; a kind of back-and-forth that happens when there is a live performance—whether it is solo or group. Piano genius, Borah Bergman, is the perfect example of a soloists' relationship with himself and the audience. As he plays his two-handed figures, with each hand functioning on its own and creating its' own contrapuntal lines, the audience is sucked into the sheer force of energy that comes from Borah's creative touch. In turn, Borah can feel it and respond to it in kind. The best way to experience this is to be sitting in the audience. Recordings rarely ever capture this.

When you listen to Cecil Taylor play or some of the new crop of musicians that has sprung up from his influence, what do you hear? Some say you hear "noise" but, if you listen carefully, you will hear a musical exploration. There is always a relationship between what the soloist plays and what the rhythm section plays. In the case of a solo instrumentalist giving a solo performance, the same applies; except the relationship is between the player (his mind & spirit) and what is being related to an audience and how the audience relates to the player. There is a constant underlying feedback; a kind of back-and-forth that happens when there is a live performance—whether it is solo or group. Piano genius, Borah Bergman, is the perfect example of a soloists' relationship with himself and the audience. As he plays his two-handed figures, with each hand functioning on its own and creating its' own contrapuntal lines, the audience is sucked into the sheer force of energy that comes from Borah's creative touch. In turn, Borah can feel it and respond to it in kind. The best way to experience this is to be sitting in the audience. Recordings rarely ever capture this.

When listening to free-form avant-jazz, it may seem like anarchy rules, but if you listen closely, there are many things happening at once and they are happening with a purpose in mind. Sometimes it is to create dissonance. Sometimes to create tonality and sometimes chaos rules, but for only a brief moment; because the masters understand that the rules of harmony?" yes, harmony—cannot be sustained by chaos. This is where the conflict lies. Some of the so-called avant-garde musicians fail to realize that without a sense of harmony it is not music. When I say harmony, it does not mean the ideological meaning of what we think of as traditional harmony. In the 21st Century, harmony consists of many things: including tone clusters and abnormal dissonances. Add to the mix the single note lines and uncommon or unnatural intervals and the individual quirks of each instrument (horns- squeaks. honks etc,) and there is enough to bend an audience out of shape—make them angry, or just leave! In some cases, they actually stay and cheer or give the artist a standing ovation. Why is that? Because, in the hands of a real master, the music can be exciting, emotional, funny, demanding, exhausting, entertaining, even spiritual; and it will bring you to places and heights you rarely experience in other settings. One thing is for sure: you will not be bored. The trip you take is worth the price of admission, but the price of admission must be worth the trip!

Many musicians claiming to be avant-garde or new music aficionados are in reality failed jazzers who are not very good avant-garde players either. Put simply, they can't play. Somewhere along the line someone should have told them to stop. But in the arts, it is forbidden to dictate to another what he/she should play. It is not up to us to tell another to give up and go home, but we can guide them by suggesting they study more. Who are we to know what art really is? There are some who have the audacity to claim they know what jazz is or suppose to be. They never consider the "out players" as jazz players even though many of the avant musicians are better-trained in both the classical and jazz worlds and are just as comfortable playing "inside" as they are playing "outside". They are dismissed as being non-essential. Consider pianist Michael Jefry Stevens or trumpeter Dave Douglas or trombonist Steve Swell. Many of them choose to play that way because it is an extension and a growth of who they are. They see themselves as explorers, exploring uncharted territories. The ride is exhilarating! To them, it's all music. How simple it would all be if we all looked at it that way.

Many musicians claiming to be avant-garde or new music aficionados are in reality failed jazzers who are not very good avant-garde players either. Put simply, they can't play. Somewhere along the line someone should have told them to stop. But in the arts, it is forbidden to dictate to another what he/she should play. It is not up to us to tell another to give up and go home, but we can guide them by suggesting they study more. Who are we to know what art really is? There are some who have the audacity to claim they know what jazz is or suppose to be. They never consider the "out players" as jazz players even though many of the avant musicians are better-trained in both the classical and jazz worlds and are just as comfortable playing "inside" as they are playing "outside". They are dismissed as being non-essential. Consider pianist Michael Jefry Stevens or trumpeter Dave Douglas or trombonist Steve Swell. Many of them choose to play that way because it is an extension and a growth of who they are. They see themselves as explorers, exploring uncharted territories. The ride is exhilarating! To them, it's all music. How simple it would all be if we all looked at it that way.

Some of the so called "out players" are not educated in the ways of music. Meaning, they have not studied or do not comprehend what came before and what needs to be done to move forward. Should the music move forward? Absolutely! Before it can move forward, the past has to be mastered. Should every up-and-coming trumpet player emulate Miles Davis and a whole slew of other influences before he discovers his own sense of artistry? No. Does this mean that every kid who wants to be a professional musician should get a college degree? No. But if you want to advance the music, you must go back in time and at least understand the history of the music, harmony, improvisations and how the music progressed through the years with each new innovator.

Whether you study with private teachers, go to college, or study on your own, it is a process that can't be avoided. Learning to be proficient on your instrument is essential if you are someday to become a new force to be reckoned with. John Coltrane was a schooled musician. Years after his formal musical training he continued to study and practice and absorb as much music as he could. He would practice on his breaks while playing with Miles Davis. He is only one example. Every musician who is serious about his art form puts in endless hours of study and practice. When they don't physically have the instrument in their hands, they mentally practice. They dream about practicing and music. Music consumes their lives. Anyone who was a musical giant and innovator did not take the past for granted. If you are to be taken seriously, you can't disregard the past. It is the past that is subliminally in your subconscious and unwittingly guides you. In the world of music, especially the "avant-garde", the musicians lot is to constantly prove him/herself to the rest of the world and to be taken seriously. It is common to hear at any given moment at any concert: "but can he/she really play?"

How far out is too far out? There's no such thing.

Discuss How Far Is Too Far Out? on the AAJ Bulletin Board.

Photo Credit

Thelonious Monk by William P. Gottlieb

Dave Douglas by Michael Kurgansky

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.