Home » Jazz Articles » Live Review » Wallace Roney Quintet: The History of Jazz in Thirty Min...

Wallace Roney Quintet: The History of Jazz in Thirty Minutes or Less or Your Money Back

Ever since Wynton Marsalis came under the tutelage of Stanley Crouch, jazz has never been the same. From their pulpit high on Lincoln Center, the two have created a significant schism in the jazz community. Crouch’s opinions have been apparently unorthodox and controversial, and his insistence on jazz “purity” (whatever that term is supposed to mean), has split the jazz community into two camps. Personally, I have always been in the camp who places value on innovation and am glad to hear the introduction of other influences, including electronic ones, into the lexicon.

I never anticapated having to re-evaluate my own standpoint.

On June 23rd, the Wallace Roney Quintet played at the Regattabar in Boston. My only familiarity with the work of Wallace Roney was with the Miles Davis tribute band circa 1992, which was Miles’ Second Great Quintet minus Miles plus Roney, and Miles at Montreaux, where Roney played some of Miles’s harder trumpet parts from the Gil Evans collaboration. That body of work is impressive indeed, and Roney’s ability to sit in the place of the great master of space and tension was uncanny. So let it be known that I did not have much of a preconception when I sat down at the table, front row, center stage, and strapped myself in for one hell of a concert. And that is exactly what I got.

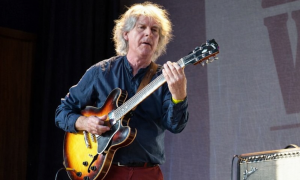

From Mr. Roney’s opening note, I was simply astounded, and for a multitude of reasons. First and foremost, the group was in top form – the show was perhaps the greatest jazz performance I have seen to date. The quintet, including Adam Holzman on keys, Wallace Roney’s younger brother Antoine Roney on tenor, soprano, and bass clarinet, Buster Williams on bass, and Lenny White on drums, explored compositions from their most recent album, No Room for Argument. A number of pieces I heard sounded familiar, some more than others. The concert opened up with Monk’s “Straight, No Chaser,” where the group managed to stay quite tethered to structure at first, and about halfway through, letting loose into a very free hardcore blowing session that peeled the paint off the walls with the power of a huge explosion. It was going to be a great night.

Next up was "Filles de Kilimanjaro", the Miles Davis/Gil Evans composition from the album of the same name, which segued into “A Love Supreme” (note: I had not heard the album which they were promoting, and the aforementioned piece is a medley from the album, now entitled “Homage and Acknowledgement”). This piece signified the only time Antoine Roney used the bass clarinet, a disappointment considering his ability on the horn and the textures it supplies to the group’s sound. I was also surprised to hear the tasteful use of electronics by Mr. Adam Holzman. He employed the use of no less than four keyboards: a traditional piano, a Rhodes, a Korg, and a Kurzweil. When it comes to electronics, history has taught us that ambitions can often lead to pure stink at times, but Mr. Holzman, a pioneer of MIDI and a key part of Miles’ 80’s groups, always appropriately utilized the proper sounds for either embracing support or stunning solos. Wallace Roney’s playing reminisced Mile’s playing during his late Sixties electric period, rapid fire notes ascending the scales with raw power and excitement. Mr. White’s playing combined the sheer force and swing of Elvin Jones with a much needed sense of dynamics.

This sense of taste and touch by Mr. Roney was never more present than on the fourth piece of the evening, a ballad penned by Buster Williams entitled “Christina.” From the second Wallace Roney blew the air from his lungs into that Harmon-muted trumpet, I was thrown into memories of the hours and hours spent in my room, wondering how Miles achieved that much tension and emotion in pieces like “It Never Entered My Mind.” Wallace Roney’s playing was stunning, breathtaking. I sat there in awe as this man, this mortal creature just as I, played something so beautiful that I simply cannot put it into words. As he played the melody, which reminded me of Bernstein’s “Maria”, and improvized over subsquent choruses, I began to understand how this man had fully integrated the sounds and lessons of Miles Davis and incorporated them into his own music. Music so beautiful cannot simply be mimicked. An entire lifetime of human experience goes into a performance like that, and hours spent listening to recording and even copying the playing of a great balladeer would leave one short. This is where my dilemma arose.

Were Stanley Crouch and Wynton Marsalis right? Was mimicry for the sake of purity and aesthetics a worthwhile endeavor? The answer, or rather the value judgment, would argue no. Wallace Roney’s improvizations, his musings, his emotions, all creeping out the end of that trumpet utilize a particular tone and approach for his own expressive purposes. To create such personal music is not something that can be mined from old recordings and performances. To fault him for such an endeavor would be similar to chastising Roy Eldridge for sounding too similar to Louis Armstrong. Wallace Roney has integrated the lessons taught by Miles Davis, and he pays significant homage too them with his quintet, while also nodding his proverbial hat to the free jazz and avate-guarde movements at the same time. He is using and fully integrating the lessons of all that modern jazz has taught us in the last fifty years, and creating an exciting hybrid. We should be both thankful and anticipatory.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.