Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Point From Which Creation Begins: The Black Artists' Gro...

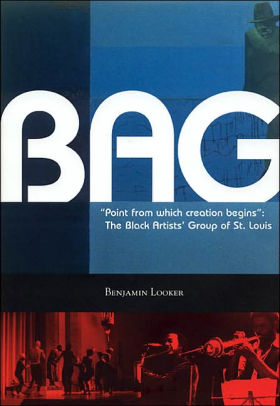

Point From Which Creation Begins: The Black Artists' Group of St. Louis

Benjamin Looker

Benjamin LookerPoint From Which Creation Begins: The Black Artists' Group of St. Louis

Missouri Historical Society Press

Distributed by University of Missouri Press

316 pages

ISBN: 1883982510

2004

When I arrived in St. Louis, Missouri from the West Coast, I learned quickly about the city's legacy. The first piece of advice I received when looking for a place to live was "don't go north of Delmar." White people, I was told, don't live there. A grocery store on the borderline, part of a larger chain, was colloquially termed the "Nairobi National" because of the color of its customers. The housing projects in the northern part of the city were notorious for crime, poverty, and just plain bad juju.

I was to learn more about that a couple of years later when I casually befriended a (black) man named Percy at a White Castle and helped him transport a (probably stolen) TV to his "cousin" Skip's house, deep in the ghetto. Skip threatened me with a gun when he saw what color I was, but Percy explained I was a member of the mafia and he relented. (I am as Scandinavian as they get, which made the whole situation all the more humorous, in retrospect at least. I guess there's something true about the adage that all white people look the same.) Through the course of the evening, Percy picked up two prostitutes, smoked pot and crack, and took another woman home with him for the night. The police were actually parked two blocks away, but they were busy, as Percy explained, "looking after folks like you."

That story is 100% true. And no, I wasn't high. I had a feeling sobriety was important for survival.

The racial legacy in St. Louis dates back to Mississippi trading days, westward expansion, and the Courthouse where slaves were sold and the Dred Scott case was argued. It still stands. City planners crammed African Americans into a zone in the northern part of the city through a systematic policy of institutionalized racism, realized in part through housing development and urban zoning practices. There's a very good reason urban St. Louis didn't vote for Senate candidate John Ashcroft in 2000, instead helping elect his dead competitor, whose wife Jean Carnahan eventually took the position. (Ashcroft's friends in the Republican Party eventually elevated him to Attorney General, where he probably did more damage than he could ever have done as a Senator, but nobody could have known that at the time.)

Politics and personal experience aside, one of the products of this legacy is a sweet one for jazz, and it was born in the very center of the black urban experience. The Black Artists' Group (BAG), a collective of poets, actors, visual artists, and musicians, was formed in 1968. It was a fundamentally proactive group forged from and located within St. Louis's African American community. Among the musical members of the BAG: Hamiet Bluiett, Oliver Lake, and Julius Hemphill, who led numerous projects and eventually formed the BAG's most prominent and longest-lasting legacy, the World Saxophone Quartet, with David Murray. The BAG lasted but four brief years, unlike Chicago's parallel Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), which still provides musical instruction today.

Author Benjamin Looker, who first tuned into the BAG while a student at Washington University in St. Louis, has assembled the definitive story of the collective in the form of Point From Which Creation Begins , named after an Oliver Lake recording from 1971. Looker, who reported on the subject for AAJ back in 2002 , takes a systematic approach to the "Poets of Action" who dominated the grassroots experimental arts scene of St. Louis around 1970. The holistic view he adopts in his text is absolutely key to making it work. There's no way to look at this group in isolation.

That's because the BAG was not so much an institution as a fluid community group with ties to society, culture, race, politics, economics, and artistic innovation in the fields of experimental ("avant-garde") theater, painting, poetry, and music—often built around improvisation and usually aimed at forming meaningful and lasting connections with its (mostly black) audience. The Black Arts Movement of the '60s centered around mobilizing and empowering African Americans through creative expression, and it had deep roots in Los Angeles, Chicago, New York, Detroit, and several other cities during the period.

Looker's seven main chapters move in a logical procession through examination of St. Louis' history and roots, the foundations of the Black Arts Movement, the founding of the BAG, the multimedia relationships among its members, and a focus on musicians through their work in St. Louis and their departure to Europe and eventually the New York loft scene. Photos appear interspersed throughout, and there's a hefty collection of footnotes and references at the end for scholarly types to explore, plus a list of recordings from the period.

One of the things Looker emphasizes is the ways the group managed to recruit funding, which in some senses was crucial to its founding as well as its dissolution. There was always some controversy in the group about how to accept money from white liberals and foundations, and its outspoken politics of Black Power and tell-it-how-it-is presentations of race relations. In the history of the group, every member was black except for one: Muthal Naidoo, a South African expatriate of Indian ancestry who participated in the theater arm of the collective. The audience, with whom the BAG insisted on maintaining interactive relationships, was mostly black but definitely had a white component as well.

While Point From Which Creation Begins does deal primarily with the BAG, it touches on related events in other cities. But most importantly, it provides a template for focused creativity as a tool for social mobilization. Portia Hunt's description of events as a "meta-analysis, a performance inside a performance" holds true in many ways, as it turns out.

Art collectives have been an essential part of the musical history of the United States, and they've been particularly important in the development of jazz in the days since its transition from popular music to "art music" to underground culture. The do-it-yourself ethic that dominated the BAG's empowerment thinking persists in many forms today, including most recently the use of the internet to disseminate information on music and musicians, and the rise of independent record labels as a means for making meaningful connections with audiences everywhere. Local action can transform into both local and global influence, if channeled the right way.

Suggested reading:

Poets of Action: The Saint Louis Black Artists' Group, 1968-1972 by Benjamin LookerTags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.