Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » Circling Om: An Exploration of John Coltrane's Later Works

Circling Om: An Exploration of John Coltrane's Later Works

Om means the first vibration - that sound, that spirit that sets everything else into being. It is the Word from which all men and everything else comes, including all possible sounds that man can make vocally. It is first syllable, the primal word, the word of power.

—The Major Works of John Coltrane, Sleevenotes [Om recorded Oct 1965]

Elvin Jones left John Coltrane's group in January 1966. A couple of months afterwards he declared: "At times I couldn't hear what I was doing—matter of fact, I couldn't hear what anybody was doing. All I could hear was a lot of noise."1 But, shortly after Coltrane's death in July 1967, Jones defended the saxophonist's late music: "Well, of course it's far out, because this is a tremendous mind that's involved, you know. You wouldn't expect Einstein to be playing jacks, would you?" (radio interview)2

This amounts to a plea for understanding Coltrane's avant-garde music. I suppose you could say that Jones was attempting to see the best side of a man who had just died and who Jones revered (he compared him to an angel elsewhere). That that's all there is to it. But, still, it does stand in direct contradiction to his earlier statement.

In the radio interview, Jones compared Coltrane to Einstein—i.e. implying that Coltrane was a genius and that's why his late music was so difficult to grasp. For the same reason relativity is difficult to grasp. Because it is at genius-level and revolutionary. I'm pretty sure Jones was saying that.

But there is a potentially deeper way of looking at Elvin's comment; it is actually a reworking of Einstein's famous statement 'God does not play dice'—which was Einstein's answer to the apparent chaos of the Universe. Here Jones was reversing his view that Coltrane's late music was noise—that is chaos—instead asserting that it was the product of a "tremendous mind," and thus, implicitly, difficult to grasp. The deepest level of meaning involved in this comment identifies both Einstein—and thus Coltrane—with God. For, in Elvin's statement, it is Einstein—and implicitly Coltrane—who doesn't play with jacks (i.e. a game of chance), while in Einstein's it is God who does not play at the game of chance. This would be in line with Elvin's conception of Coltrane as an angel—i.e. someone through whom God worked. And, indeed, God would be difficult to grasp.

Well, perhaps I am reading too much into the statement. This sort of deconstruction depends on the assumption that Jones was a kind of instinctive poet, making a terse statements full of profound meaning. But then he wouldn't have to do it all the time. Perfectly ordinary people do sometimes make profound, poetic statements about those they love. And moreover, Elvin's procedure is thoroughly jazz-like, taking a well-known line and remaking it; creating new meaning in the way of an improvising soloist. But, in this case, he is using words instead of notes.

Part 1: The Sources of Nature

II

The last session Jones did with Coltrane was Meditations , recorded 23rd November 1965, one of the saxophonist's major statements from his late period. The sleevenotes contain a number of interesting passages, including this:

The last session Jones did with Coltrane was Meditations , recorded 23rd November 1965, one of the saxophonist's major statements from his late period. The sleevenotes contain a number of interesting passages, including this: "Once you become aware of this force for unity in life...you can't ever forget it. It becomes part of everything you do. In that respect, this [ Meditations ] is an extension of A Love Supreme since my conception of that force keeps changing shape. My goal in meditating on this through music, however, remains the same. And that is to uplift people, as much as I can. To inspire them to realize more and more of their capacities for living meaningful lives. Because there certainly is meaning to life."

In my opinion, when Coltrane is saying "there is..meaning to life," it is more or less the same as saying "there is a God" or "things do make sense." It is once more the idea that the Universe,...or Life,...or whatever...is not chaos. That things do add up/make an overall sense because somewhere there is some underlying thing that gives order. Coltrane's goal in music, is to convey that sense of underlying order—which he senses—so that others may also experience it. He views his music, essentially, as an antidote to existential despair.

The "force for unity" is this underlying source of order. What is interesting is that Coltrane says his "conception of that force keeps changing shape"—which is kind of mindboggling in itself, if one thinks of all the iterations Coltrane might have gone through in his cosmic unifying force. And he doesn't get any less mindboggling either, asserting that "[ Meditations ] is an extension of A Love Supreme since my conception of that force keeps changing shape." That is to say that, between A Love Supreme (December 1964) and Meditations (November 1965) Coltrane's idea of the underlying force for unity—that which gives order in the Universe—has changed, and that this has in turn resulted in a change in his music. So, therefore, the substantial difference in musical approach between A Love Supreme and Meditations derives, at least in part, from a spiritual change in Coltrane. Between the two recordings, his conception of the "force for unity" in the Universe has changed—and his music, in which he meditates on this force, has therefore also changed.

III

Given all this, it evidently matters to know just what Coltrane's conception of the "force for unity" was during A Love Supreme and, then again, what it was during Meditations. Unfortunately the guy was rather reticent—not just generally, but also concerning his underlying philosophy:

[Q]...do you feel that you want [your audience] to understand other things than what you're doing musically, and that you have some responsibility for it?

...Do you make any attempt, or do you feel that you should make any attempt, to educate your audience in ways that aren't strictly musical?

[Coltrane] Sure, I feel this, and this is one of the things I am concerned about now. I just don't know how to go about this. I want to find out just how to do it. I think it's going to have to be very subtle; you can ram philosophies down anybody's throat, and the music is enough. That's philosophy. I think the best thing I can do at this time is to try to get myself in shape and know myself. I believe that will do it, if I really can get to myself and be just as I feel I should be and play it. And I think they'll get it...3

Which is kind of obscure. But anyway. One thing that one gets from it is that, once again, Coltrane considered his music equivalent to metaphysically profound concerns. And one can work with that, for this deep seriousness comes through in all the things he says. For example here:

All a musician can do is to get closer to the sources of nature, and so feel that he is in communion with the natural laws. Then he can feel that he is interpreting them to the best of his ability, and can try to convey that to others.4

The idea of interpreting "the sources of nature" is pretty similar to the idea of idea of meditating on "the force for unity." Basically Coltrane has the idea of getting down to nuts and bolts of the universe, conceived in whatever way, and then making a music that is, on some level a discourse about them. That idea also occurs in this:

"I remember talking about Einstein with Coltrane while we were having an egg cream at the drugstore on St. Marks Place and Second Avenue. Actually he was talking about numbers and their relationship to music, how intervals affected certain kinds of chords and how they could be used to create a different order of music. He brought up the theory of relativity. To him, it meant that many things already existing had a relationship in music, and it was up to the musician to discover these relationships and express them musically. I saw Coltrane for the last time in March 1967 at the health food store on Broadway and Fifty-seventh Street. We picked up the same subject of relativity almost exactly where we broke off our previous conversation. More than anything else, recall him saying, "The Universe is always expanding.""5

In this case the nuts and bolts are scientific, rather than spiritual. But there is something else—we're back to Einstein and Coltrane. Remarkably, and mindbendingly, Coltrane was attempting to make a music transposing relativity into music. This has an evident bearing on Elvin's comments. Although short of full proof, the suggestion I want to make is that this is the basis of Elvin's comparison of Coltrane with Einstein. That is Jones was aware that Coltrane was attempting to create music drawing on Einstein's concepts.

IV

A statement by Alice Coltrane bears on this:

[Alice C.] The use of the term [Jazz], I feel, is inadequate in its description of the music created through John. A higher principle is involved here. Some of his latest works aren't musical compositions. I mean they aren't based entirely on music. A lot of it has to do with mathematics, some of it on rhythmic structure and the power of repetition, some on elementals. He always felt that sound was the first manifestation in creation before music...6

And another one:

...He was doing something with numbers once; he was doing something from a map he drew—sort of like a globe—taking scales from it, taking things from it. And he was continually changing and continually doing things like that, and another day it would be something else. Working with harmonics, working with chromatics, microtones, working with overtones, adding octaves to his instrument.7

While Alice doesn't mention Einstein, the idea that a "lot [of Coltrane's later music] has to do with mathematics" is surely suggestive in light of the above discussion—as is his working from numbers, and the idea that Coltrane's music was not strictly Jazz but was about some "higher principle." In more general terms, all this seems to flesh out the view that Coltrane was trying to reflect the nuts and bolts of the universe in his music.

The trouble is it also adds yet more layers of complexity and, I suppose, potential confusion too. I mean, we don't seem much closer to finding what Coltrane's conception of the "force for unity" was during Love Supreme , or what it was during Meditations or how it was reflected in the music.

What we can say, I think, is that Coltrane's "higher principle" or "force for unity" or "sources of nature" wasn't simply a metaphysical thing—I mean it wasn't simply God—but it incorporated elements from science as well. Coltrane's says as much in this statement:

"I'm interested in all the sciences—metaphysics, astrology, astronomy, mental physics..."8

The other thing that one can say is to do with the nature of Coltrane's late music. It is often suggested, implicitly or sometimes explicitly, that all Coltrane was doing in this was going on stage and blowing. No thinking, just blowing. The music is then, its detractors assert, naturally mindless chaos. What these people scrupulously avoid doing, however, is reading what Coltrane said. We have done that. And what we can see is that Coltrane thought very long and hard—and with deep seriousness—about his music. Moreover, it is evident that he didn't just go up to the bandstand and blow. The testimony of Alice Coltrane and Amram clearly indicate that this music had structure—structure at least partly imported from outside Jazz, to be sure—but structure nevertheless.

Part 2: Om

V

While Coltrane's late music isn't chaos, it certainly frightens people. The word this music most brings to my mind is "awe." That is late Coltrane is awesome music with the awesome nature front and centre. The dictionary definition of awe is "reverential fear or wonder"—and I think there is something terribly fearsome about Coltrane's later music.

While Coltrane's late music isn't chaos, it certainly frightens people. The word this music most brings to my mind is "awe." That is late Coltrane is awesome music with the awesome nature front and centre. The dictionary definition of awe is "reverential fear or wonder"—and I think there is something terribly fearsome about Coltrane's later music. A google search for "Coltrane awe" gives a lot of entries, by no means all for this later period. Conceiving Coltrane's music as awesome is not an original thought—Though the underlining of the fearsome aspect is. But I think that, while there is a particularly awesome aspect to Coltrane's sensibility (for example on Giant Steps), it comes to the fore in this period. That is this is "scary music."

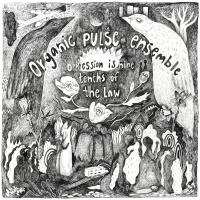

So now we can come to the title track of this article, Om —a recording made October 1st 1965. Om qualifies as fearsome. There are moments, particularly during the closing unison passages, when it feels like one is getting beaten over the head with a blunt instrument. It becomes unbearable. But I believe that such an effect was in line with Coltrane's intentions. The sleevenotes state:

"Om means the first vibration—that sound, that spirit that sets everything else into being. It is the Word from which all men and everything else comes, including all possible sounds that man can make vocally. It is first syllable, the primal word, the word of power."9

Coltrane is trying to evoke the voice of God at the Dawn of Creation in this track. But hearing the voice of God at the Dawn of Creation is much like confronting the face of God. This is going to be an awesome and overwhelming experience—which one can only take for so long. But I think there ought therefore to be some unbearability in the music as well —because one should neither really be able to look God full in the face, nor hear his voice without quailing somewhat. So then Om must be "difficult."

VI

My problem with Om is that I don't think it's all that successful. It's not that it's a bad record, rather that it's not somehow as deep, coherent and resonant as either the best of Coltrane's late work—or as, really, the voice of God at the dawn of Creation ought to be. In a way, perhaps, Coltrane fall prey to the very thing he evokes, the impossibility of looking God full in the face. But I think there is something rather representative about Om , if not of God, then of Coltrane's late work. The awesomeness of late Coltrane reaches its extreme in the passages in Om where one just wants the music to stop.

My problem with Om is that I don't think it's all that successful. It's not that it's a bad record, rather that it's not somehow as deep, coherent and resonant as either the best of Coltrane's late work—or as, really, the voice of God at the dawn of Creation ought to be. In a way, perhaps, Coltrane fall prey to the very thing he evokes, the impossibility of looking God full in the face. But I think there is something rather representative about Om , if not of God, then of Coltrane's late work. The awesomeness of late Coltrane reaches its extreme in the passages in Om where one just wants the music to stop. This is not the only representative aspect to Om. For example, Ekkehard Jost sees it as a clue to Coltrane's late musical conception:

"Coltrane's stylistic evolution had led to a phase of experimentation with vertical, harmonic development in the early Sixties, to a modal linearity. Now came a third phase, which would have to be called—in simplified terms—sound exploration. The title Om , which Coltrane recorded with [Pharoah] Sanders in October 1965, has, in addition to its religious and philosophical implications, a further import, which can be taken as a clue to Coltrane's musical conception: as Coltrane says, the Hindustani word Om means among other things, "All possible sounds that man can make vocally."

Although the phase of sound exploration was triggered by Ascension , it went a good deal further in its consequences. As sound came to be the decisive principle, older categories of musical organisation lost importance."10

The use of sound as an organising principle is key to late Coltrane. Morover, I believe, it is intrinsically related to the awesome elements in this music. For Coltrane uses evocative sound exploration as the core of the power of the music. This is particularly evident in Om , where, as stated, the unison passages evoke the power of the voice of God at the dawn of creation. As Coltrane puts it: "It is the primal word, the word of power." which is also the "that sound, that...sets everything else into being.." Pharoah Sanders, central to the late music, was a "sound" player. Coltrane persistently picked out the "strength" of his playing and lauded him for it. The idea of a "force for unity" is itself part of the conceptualization of Coltrane's late music. The words "force," "strength" and "power" all fit together as part of a new musical conception.

VII

In terms of spirituality, I think it likely that Coltrane was getting his ideas about Om out of Paramahansa Yogananda's Autobiography of a Yogi. John had this book, and PY's name often comes up in anectdotes about JC. The description of Om in the sleevenotes (above) is a kind of a fusion of Christian ideas about The Word Of God at the beginning of Creation and Om, the Indian conception of the primal sound—which is basically what PY does in his book. For example:

In terms of spirituality, I think it likely that Coltrane was getting his ideas about Om out of Paramahansa Yogananda's Autobiography of a Yogi. John had this book, and PY's name often comes up in anectdotes about JC. The description of Om in the sleevenotes (above) is a kind of a fusion of Christian ideas about The Word Of God at the beginning of Creation and Om, the Indian conception of the primal sound—which is basically what PY does in his book. For example: ..."The creative voice of God I heard resounding as Aum [note see below], the vibration of the Cosmic Motor."[p167-8]

[Note p167-8] "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God" John 1:1 ..."the threefold nature of God as Father, Son, Holy Ghost (Sat, Tat, Aum in the Hindu scriptures). God the Father is the Absolute, Unmanifested, existing beyond vibratory creation. God the Son is the Christ Consciousness (Brahma or Kutastha Chaitanya) existing within vibratory creation; this Christ Consciousness is the "only begotten" or sole reflection of the Uncreated Infinite. The outward manifestation of the omnipresent Christ Consciousness, its "witness" (Revelation 3:14), is Aum, the Word or Holy Ghost; invisible divine power, the only doer, the sole causative and activating force that upholds all creation through vibration. Aum the blissful Comforter is heard in meditation and reveals to the devotee the ultimate Truth, bringing "all things to...remembrance."

But PY also says:

..." nature is an objectification of Aum [=Om], the Primal Sound or Vibratory Word....11

The outward manifestation of the omnipresent Christ Consciousness, its "witness" (Revelation 3:14), is Aum, the Word or Holy Ghost; invisible divine power, the only doer, the sole causative and activating force that upholds all creation through vibration. Aum the blissful Comforter is heard in meditation and reveals to the devotee the ultimate Truth, bringing "all things to...remembrance."12

If, Coltrane was indeed following PY, this would make Om the "force for unity"- in that everything else is an "objectification" of it. One also has evidence for this if one follows up the source of the chant that begins and ends the track:

"Rites that the Vedas ordain, and the rituals taught by the scriptures,

All these am I, and the offering made to the ghosts of the fathers,

Herbs of healing and food, the mantram, the clarified butter:

I the oblation and I the flame into which it is offered.

I am the sire of the world, and this world's mother and grandsire I am He who awards to each the fruit of his action:

I make all things clean

I am OM...

According to John Page, posting to Coltrane-L on 19th Oct 1998:

The passage quoted in OM are from the 9th Book of the Bhaghavad Gita, and match the Prabhavananda/Isherwood translation word for word (p104). This translation is from the mid 40's, so it seems reasonable that this was the one used.

One interesting thing is that the part quoted only goes about halfway. It continues as:

"I am absolute knowledge

I am also the Vedas— the Sama, the Rik and the Yajus,

I am the end of the path, the witness, the Lord, the sustainer;

I am the place of abode, the beginning, the friend and the refuge;

I am the breaking apart, and the storehouse of life's dissolution:

I lie under the seen, of all creatures the seed that is changeless.

I am the heat of the sun; and the heat of the fire am I also;

Life eternal and death. I let loose the rain, or withold hit.

Arjuna, I am the cosmos revealed, and its germ that lies hidden."

p104-5

That Om is identified with "the seed" "of all creatures," "the cosmos revealed, and its the germ that lies hidden" in Coltrane's source identifies it with the basis of everything in the Universe—It is then, more or less, "the force for unity" in the Universe. Indian thought is not my field, so this conclusion may be flawed, but my view is that the "force for unity" on which Coltrane meditates in Om is Om. But Om itself was recorded less than 2 months (Oct 1 1965 23 November 1965) before Meditations —where Coltrane makes his "force for unity" statement. Because Coltrane's musical conception didn't change over that period, Coltrane's "force for unity" presumably wouldn't have done so either —so Om would be the "force for unity" Coltrane is talking about on Meditations too. In fact, the logic of Coltrane's position is that Om would have been his "force for unity" from preceding Ascension , as this is when the major change in his musical conception occurred.

The problem with this is that "force for unity" implies something holding the universe together when it might fall apart. But that isn't a spiritual/religious way of looking at things (or at least that's how it seems to this atheist). That way of looking at things implies that the universe finds its origin in whatever God or Prime Mover is believed in. God precedes the universe, as it were. This statement implies that if the "force for unity" were taken away the Universe might collapse into chaos. But that doesn't make any sense, a religious person doesn't believe in this sort of "death of God." But Coltrane might have been talking about a conceptual force for unity. That might work:

"Once you become aware of this force for unity in life...you can't ever forget it. It becomes part of everything you do. In that respect, this [ Meditations ] is an extension of A Love Supreme since my conception of that force keeps changing shape. My goal in meditating on this through music, however, remains the same. And that is to uplift people, as much as I can. To inspire them to realize more and more of their capacities for living meaningful lives. Because there certainly is meaning to life."

I think his idea of a "unity in life" is an act of faith rather than an intellectual process. He intuits a unity. That would be his religious/spiritual experience out of which everything else comes. There is a unity to life. There is meaning. Things do make sense. I think that's the core of it.

The other thing that comes out of this is some handle on how to treat the hyper-long meditations of his later years—those in his solos. In meditating on the "force for unity," he is by necessity meditating on all that is life—so that his solos in this period become awesome meditations on....everything.

Part 3: Cosmos

VIII

In terms of one's inner life, "everything" relates to God or whatever prime mover one's inner relationship is to. In terms of one's outer life, "everything" is the Universe. In this period, the 50s and 60s, because of the discoveries in Space and Man's first ventures off the Earth, I believe the Cosmic dimension took on a particular resonance for Coltrane—as the pendant of the internal spiritual search he was involved in. I think that is the basis for the following observations:

..."[Coltrane] had a pair of binoculars and, back in San Francisco, during the intermission from his playing at the Jazz Workshop, we'd walk ten blocks to a field down by the freeway, and he'd start looking at the stars. He knew where the Milky Way was, and everything." (Louis-Victor Mialy [remembering an event from September 1961])

Elsewhere, Mialy wrote of those intermissions:

"Coltrane looked at the sky, the stars, scrutinizing the night for a long moment of infinity as if to discover the secrets of the universe, a universe that appeared to trouble him with its complexity, its power and its unknown dimensions...After a while, we climbed back up, slowly and always in silence, the slope to Broadway, I to recover my corner and continue to listen feverishly; Coltrane to anxiously reclaim his saxophones and his work of research, his mysterious quest...."13

So this is a spiritual search. My image of Coltrane is of a voyager over strange lands to some far away goal he senses but barely feels. There is a yearning in his tone which speaks of his deep longing for meaning. So I can quite imagine him scouring the heavens for meaning. And, as a general statement, Coltrane did have an interest in space throughout the 60s. Thus:

"Stacked neatly on a table were copies of The Negro Digest, "The Universe and Dr. Einstein," "Guide to the Planets" and "Astronomy Made Simple."14

Tracks titles:

Tracks titles: Live in Seattle (30/9/1965): Track 1 Cosmos.

Interstellar Space (22/2/1967): Track 1 Mars; Track 3 Venus; Track 5 Jupiter; Track 6 Saturn.

Also, in The Complete 1961 Village Vanguard Recordings Sleevenotes, David Wild reports:

"Subsequent research suggests that Coltrane may at one point have called [His composition Brasilia] "Neptune..."The modal Miles Mode is listed on the Vanguard Material as "The Red Planet."

While this does not seem to have been quite so all encompassing as Coltrane's overall relationship with God in whatever form, nevertheless the evidence is of ongoing interest in space. Judging by the existence of a whole studio album (his final one) on this theme in 1967, his interest seems to have gained in intensity towards the end of his life.

One can see this interest again in David Amram's reminiscence:

"I remember talking about Einstein with Coltrane while we were having an egg cream at the drugstore on St. Marks Place and Second Avenue. Actually he was talking about numbers and their relationship to music, how intervals affected certain kinds of chords and how they could be used to create a different order of music. He brought up the theory of relativity. To him, it meant that many things already existing had a relationship in music, and it was up to the musician to discover these relationships and express them musically. I saw Coltrane for the last time in March 1967 at the health food store on Broadway and Fifty-seventh Street. We picked up the same subject of relativity almost exactly where we broke off our previous conversation. More than anything else, I recall him saying, "The Universe is always expanding.""15

IX

Looking at the last sentence of Amram's reminiscence, the expansion of Universe was discovered in 1929 by Hubble. It was taken up by George LeMaitre, who used it as evidence for his Big Bang theory of the Universe. Le Maitre's theory was based in the Einstein's relativity, which, in its raw state, implies a Universe which is either expanding or contracting. Hubble showed that it was expanding.

Anyone as interested in space as Coltrane was would have been aware of the Big Bang theory. "The Universe and Dr. Einstein" (which Coltrane owned, see above) gives an outline, stating amongst other things:

"Since all of [the] remote galaxies, without exception, are moving away from us and from each other, one must conclude that at some epoch in time all of them were clustered together in one fiery, inchoate mass."16

But a more profound reason to believe in Coltrane's interest in the Big Bang is that, in these years, it became the ruling theory in cosmology. This is because, in 1965, what was considered clinching evidence for the theory was presented. This was the discovery of the "background radiation" by Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson. Using an extremely sensitive antenna, and being occupied with quite some other task, they discovered what turned out to be an echo of the Big Bang. The discovery caused a revolution in Cosmology—and, again, someone as interested in space as Coltrane was certainly would have heard about it—and likely believed in it. Because most everyone believed that the Universe began with the Big Bang from then on.

X

The way Coltrane brought up the expanding universe in the context of relativity carries a strong suggestion, then, that he believed in the Big Bang theory of the Universe—that is to say he believed in a primal explosion out of which all matter in the Universe had been created (Coltrane would have been aware of this theory and its basis: see below). But we already know that he did believe in a parallel primal event. This was Om:

..."[T]he first vibration—that sound, that spirit that sets everything else into being. It is the Word from which all men and everything else comes."

To come clean now, my hunch has been that Coltrane did indeed identify Om with the Big Bang—it's been like that for maybe three years now and has been the generating force of this article. I can't prove it, but I do actually believe it. The problem mostly being that Coltrane never mentioned the Big Bang directly (at least it's not on the record).

The Big Bang view conceives of a moment when"all...galaxies...were clustered together in one fiery, inchoate mass." Or, to put it slightly differently, at this point in time everything (in all the galaxies) was clustered together in one mass. Even for unspiritual person like me, who believes in a contingent Universe, this is a remarkable thought. For at this moment, science says, everything was part of this one inchoate mass—all the bits that were to become me and all the bits that were to become the Crab Nebula and all the bits that were to become everything else were part of this one grandiose thing. I can't avoid the thought, therefore, that, if only at this one point in time, there was a unity, if not exactly to life, then to everything that would become life. For someone like Coltrane, believing in an underlying order to reality, well...One can only imagine what effect such a thought must have had one him. My sense of it is that it would have been a spiritual bombshell to him.

XI

We have been talking about Coltrane's "force for unity" a lot, but so far we have not looked at how it changed betweeen A Love Supreme and Om. OK. There are a number of changes, including a shift from gentleness to power and an emphasis on sound where none had occurred before. But I want to concentrate on something else. On A Love Supreme , he states:

We have been talking about Coltrane's "force for unity" a lot, but so far we have not looked at how it changed betweeen A Love Supreme and Om. OK. There are a number of changes, including a shift from gentleness to power and an emphasis on sound where none had occurred before. But I want to concentrate on something else. On A Love Supreme , he states: ...Words, sounds, speech, men, memory, thoughts, fears and emotions—all related...all made from one...all made into one.

Blessed be His name.

Thought waves—heat waves—all vibrations - all paths lead to God. Thanks you God.17

While on Om :

"Om means the first vibration—that sound, that spirit that sets everything else into being. It is the Word from which all men and everything else comes, including all possible sounds that man can make vocally. It is first syllable, the primal word, the word of power."18

Clearly there is a shift in emphasis from a unity in God as a general, overall entity to whom all paths lead (and from whom everything must therefore come) to the Word of God from which everything comes. Basically Coltrane has made the primal moment, at which this word of God is spoken, a key element in his conception.

Why has that occurred? Well I would like to suggest a reason. The discovery of the background radiation, effectively confirming that the Universe had begun with the Big Bang, was announced to the world in the New York Times on May 22 1965. We are postulating that this would have been a spiritual bombshell for Coltrane. Basically I want to suggest that he took on board this view, from Barnett's book:

"Man's inescapable impasse is that he himself is part of the world he seeks to explore; his body and proud brain are mosaics of the same elemental particles that compose the dark drifting dust clouds of interstellar space; he is, in the final analysis, merely an epheremal conformation of the primordial space-time field. Standing midway between macrocosm and microcosm, he finds barriers on every side and can perhaps but marvel, as St. Paul did nineteen hundred years ago, that "the world was created by the word of God so that what is seen was made out of things which do not appear."19

XII

In my view, the shift to power and sound likely came about as a result of the influence of Ayler. Both Coltrane and Ayler say that there was an important influence and power and sound were at the centre of Ayler's conception (see my forthcoming article on Ayler). As we know, Coltrane said his music had changed as a result in his conception of his "force for unity." My view is that Coltrane probably had an interest in Ayler's music, and that of other younger free musicians, but held back from a change in that direction until it was catalysed by this spiritual change. I come to that perception from this quote:

Q: "What about giving audiences a chance to catch up?"

Coltrane: "This always frightens me...Whenever I make a change I'm a little worried that it may puzzle people. And sometimes I deliberately delay things for this reason. But after a while I find there is nothing else I can do but go ahead."20

Reading between the lines, Coltrane was interested in the free music but held back from moving in that direction until change was forced on him. Because of his comments in the Meditations sleevenotes, we know that a change in his "force for unity," a spiritual change, partly caused this change in the music. But I believe that one element in this spiritual change, the belief in a primal moment, came about as a result of Coltrane's response to the scientific proof of the Big Bang. Further I believe that Coltrane would have experienced this as a spiritual bombshell—in other words, enough of a change to have had revolutionary results for Coltrane. Given that, I postulate that the spiritual change that caused Coltrane to change his "force for unity" to Om—and thus the Big Bang—was the scientific proof of the Big Bang.

Because Coltrane's music changed with Ascension , recorded June 28 1965, and the news of the Big Bang was released on May 22 1965, my conclusion is that Coltrane underwent this spiritual change between these two dates.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

John Coltrane, His Life and Music by Lewis Porter

Coltrane, A Biography by C.O. Simpkins

Autobiography Of A Yogi Paramahansa Yogananda

Chasin' The Trane J.C.Thomas

The Universe and Dr. Einstein Lincoln Barnett

The John Coltrane Companion ed. Carl Woideck

Sleevenotes to The Major Works of John Coltrane

Sleevenotes to Meditations

Love Supreme Poem by John Coltrane

Giants of Black Music Rivelli and Levin

Free Jazz Jost

Coltrane-L Archives

NOTES

1. Downbeat March 10th 1966 quoted in Porter p267

2. Porter p267 (From a radio interview in 1967)

3. Kofsky Interview 1966 in Woideck p151-2

4. Wilmer Interview 1962 in Woideck p108-9

5. David Amram quoted in Thomas p188

6. Rivelli and Levin p122 [interview July 1968]

7. Ibid p123

8. Porter p256

9. The Major Works of John Coltrane, Sleevenotes [ Om recorded 1 Oct 1965]

10. Jost p96-7

11. Paramahansa Yogananda p182

12. Ibid Note 168-9

13. Porter p256

14. The Washington Post, Sunday, June 25, 1961, p. G4 [Source: Coltrane-L post 2nd Oct 2001 by Chris DeVito]

15. David Amram quoted in Thomas p188

16. Barnett p88

17. Love Supreme Poem Dec 1964

18. The Major Works of John Coltrane , Sleevenotes [ Om recorded 1 Oct 1965]

19. Barnett p102

20. Melody Maker 14th August 1965 in Coltrane/Simpkins p192

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.